ETA Hoffmann's Opera Manifesto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darwin Prakash CV July 2021

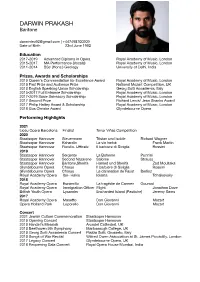

DARWIN PRAKASH Baritone [email protected] | +447498700209 Date of Birth 23rd June 1993 Education 2017-2019 Advanced Diploma in Opera Royal Academy of Music, London 2015-2017 MA Performance (Vocals) Royal Academy of Music, London 2011-2014 BSc (Hons.) Geology University of Delhi, India Prizes, Awards and Scholarships 2019 Queen's Commendation for Excellence Award Royal Academy of Music, London 2019 First Prize and Audience Prize National Mozart Competition, UK 2018 English Speaking Union Scholarship Georg Solti Accademia, Italy 2015-2017 Full Entrance Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017-2019 Susie Sainsbury Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2017 Second Prize Richard Lewis/ Jean Shanks Award 2017 Philip Hattey Award & Scholarship Royal Academy of Music, London 2016 Gus Christie Award Glyndebourne Opera Performing Highlights 2021 Liceu Opera Barcelona Finalist Tenor Viñas Competition 2020 Staatsoper Hannover Steuermann Tristan und Isolde Richard Wagner Staatsoper Hannover Kaherdin Le vin herbé Frank Martin Staatsoper Hannover Fiorello, Ufficale Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini 2019 Staatsoper Hannover Sergente La Boheme Puccini Staatsoper Hannover Second Nazarene Salome Strauss Staatsoper Hannover Baritone,Sherifa Hamed und Sherifa Zad Moultaka Glyndebourne Opera Chorus Il barbiere di Siviglia Rossini Glyndebourne Opera Chorus La damnation de Faust Berlioz Royal Academy Opera Ibn- Hakia Iolanta Tchaikovsky 2018 Royal Academy Opera Escamillo La tragédie de Carmen Gounod Royal Academy Opera Immigration Officer Flight Jonathan Dove British Youth Opera Lysander Enchanted Island (Pastiche) Jeremy Sams 2017 Royal Academy Opera Masetto Don Giovanni Mozart Opera Holland Park Leporello Don Giovanni Mozart Concert 2021 Jewish Culture Commemoration Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Opening Concert Staatsoper Hannover 2019 Handel's Messiah Arundel Cathedral, UK 2018 Beethoven 9th Symphony Marlborough College, UK 2018 Georg Solti Accademia Concert Piazza Solti, Grosseto, Italy 2018 Songs of War Recital Wilfred Owen Association at St. -

10-12-2019 Turandot Mat.Indd

Synopsis Act I Legendary Peking. Outside the Imperial Palace, a mandarin reads an edict to the crowd: Any prince seeking to marry Princess Turandot must answer three riddles. If he fails, he will die. The most recent suitor, the Prince of Persia, is to be executed at the moon’s rising. Among the onlookers are the slave girl Liù, her aged master, and the young Calàf, who recognizes the old man as his long-lost father, Timur, vanquished King of Tartary. Only Liù has remained faithful to the king, and when Calàf asks her why, she replies that once, long ago, Calàf smiled at her. The mob cries for blood but greets the rising moon with a sudden fearful reverence. As the Prince of Persia goes to his death, the crowd calls upon the princess to spare him. Turandot appears in her palace and wordlessly orders the execution to proceed. Transfixed by the beauty of the unattainable princess, Calàf decides to win her, to the horror of Liù and Timur. Three ministers of state, Ping, Pang, and Pong, appear and also try to discourage him, but Calàf is unmoved. He reassures Liù, then strikes the gong that announces a new suitor. Act II Within their private apartments, Ping, Pang, and Pong lament Turandot’s bloody reign, hoping that love will conquer her and restore peace. Their thoughts wander to their peaceful country homes, but the noise of the crowd gathering to witness the riddle challenge calls them back to reality. In the royal throne room, the old emperor asks Calàf to reconsider, but the young man will not be dissuaded. -

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S

Advance Program Notes New York Gilbert & Sullivan Players H.M.S. Pinafore Friday, May 5, 2017, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Albert Bergeret, artistic director in H.M.S. Pinafore or The Lass that Loved a Sailor Libretto by Sir William S. Gilbert | Music by Sir Arthur Sullivan First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on May 25, 1878 Directed and conducted by Albert Bergeret Choreography by Bill Fabis Scenic design by Albère | Costume design by Gail Wofford Lighting design by Benjamin Weill Production Stage Manager: Emily C. Rolston* Assistant Stage Manager: Annette Dieli DRAMATIS PERSONAE The Rt. Hon. Sir Joseph Porter, K.C.B. (First Lord of the Admiralty) James Mills* Captain Corcoran (Commanding H.M.S. Pinafore) David Auxier* Ralph Rackstraw (Able Seaman) Daniel Greenwood* Dick Deadeye (Able Seaman) Louis Dall’Ava* Bill Bobstay (Boatswain’s Mate) David Wannen* Bob Becket (Carpenter’s Mate) Jason Whitfield Josephine (The Captain’s Daughter) Kate Bass* Cousin Hebe Victoria Devany* Little Buttercup (Mrs. Cripps, a Portsmouth Bumboat Woman) Angela Christine Smith* Sergeant of Marines Michael Connolly* ENSEMBLE OF SAILORS, FIRST LORD’S SISTERS, COUSINS, AND AUNTS Brooke Collins*, Michael Galante, Merrill Grant*, Andy Herr*, Sarah Hutchison*, Hannah Kurth*, Lance Olds*, Jennifer Piacenti*, Chris-Ian Sanchez*, Cameron Smith, Sarah Caldwell Smith*, Laura Sudduth*, and Matthew Wages* Scene: Quarterdeck of H.M.S. Pinafore *The actors and stage managers employed in this production are members of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. -

Encyclopedia Dresden Nr. 14 EN

ABSENCE / ANIMALS / CARUS, CARL GUSTAV / CASTLE / COMMUNITY / DANCE / DESIRE / ESCAPE MOVEMENT / EVANESCENCE / FANTASY / FRAGMENT / GARBOLOGY / GUIDED TOUR / IDYLL / INTOXICATION / INTROVERSION / IRONY / LANDSCAPE / LOVE / MARKET / M ELANCHOLY / MYTHOLOGY / MUSIC / NATURE / RE- PRODUCTION / RESTORATION / SHADOWS / THE SUN, THE MOON AND THE STARS / SYMBOLS COUNSELLING AND PRACTICAL EXERCISES / REPLACEMENT ABSENCE Dr Anke Froehlich, freelance Art Historian in Dresden, published her doctoral thesis on “Landscape Painting in Saxony in the 2nd half of the 18th Century” (2002) Is there a God in the Landscape? Why artists “give a mysterious colour to the ordinary, and the dignity of the unknown to the common things” ANIMALS Kati Bischoffberger, Painter, Graphic Designer, Homeopath-in-training, Dresden Self-Portrait with a Sheep, or: What Art has to do with Homeopathy Dr Matthias Goerbert, Director of the Saxonian Stud Farm Administration Moritzburg, graduated about the Selection Criteria among Warm-blooded Mares Sports Equipment, Status Symbol, and Strong Friend. On the Horse Market Boom, especially for Racing Horses and heavy Warm-blooded Horses Local Historians in a Hybrid Game (Katja Hoffmann Wildner and Elke Schindler), Artists from Dresden The Marriage of the Birds—Phenomenological Local History based on a Sorbian Custom, or: Watching the Border on this side of Nebelschuetz Dr Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick, Conservator at the “Kupferstich-Kabinett” [Copperplate Museum], Dresden State Art Collections The Fly on the Apollo. The Perception of Nature -

Download Download

Angelica Forti-Lewis Mito, spettacolo e società: Il teatro di Carlo Gozzi e il femminismo misogino della sua Turandot Alla Commedia dell'Arte Carlo Gozzi si rifece, almeno inizialmente, perché gli offriva uno spettacolo da contrastare al teatro di Goldoni, di Chiari e, più tardi, al nuovo dramma borghese e alla comédie larmoyante. A questo scopo l'Improvvisa poteva offrirgli aiuti preziosi: la teatralità pura degli intrecci, svincolati da ogni rapporto con la vita reale e contemporanea; le Maschere, cioè tipizzazioni astrat- te; il buffonesco delle trovate comiche che, insieme alle maschere, escludeva ogni possibile idealizzazione delle classi inferiori, degradate a oggetto di comico; e, infine, il carattere nazionale della Commedia, che escludeva qualsiasi intrusione forestiera. Ma anche se Gozzi si erge a strenuo difensore della Commedia dell'Arte, è chiaro che le sue fiabe hanno in realtà ben poco a che fare con l'Improvvisa e il loro tono, sempre dominato da personaggi seri, è ben più drammatico, mentre le varie trame non sono ricavate dalla solita tradizione scenica ma da racconti ita- liani ed orientali, nel loro adattamento teatrale parigino della Foire. L'esotismo e la magia, inoltre, erano anch'essi elementi ignoti alla Commedia dell'Arte e la lo- ro fusione con la continua polemica letteraria sono chiara indicazione di come il commediografo fosse ben altro che un mero restauratore di scenari improvvisati. Trionfano nelle fiabe i valori tradizionali, dall'amor coniugale {Re Cervo, Tu- randot, Donna serpente e Mostro Turchino), all'amore fraterno, la fedeltà e la virtù della semplicità (Corvo, Pitocchi fortunati e Zeim re de' Geni). -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

The German Romantic Movement

The German Romantic Movement Start date 27 March 2020 End date 29 March 2020 Venue Madingley Hall Madingley Cambridge CB23 8AQ Tutor Dr Robert Letellier Course code 1920NRX040 Director of ISP and LL Sarah Ormrod For further information on this Zara Kuckelhaus, Fleur Kerrecoe course, please contact the Lifelong [email protected] or 01223 764637 Learning team To book See: www.ice.cam.ac.uk or telephone 01223 746262 Tutor biography Robert Ignatius Letellier is a lecturer and author and has presented some 30 courses in music, literature and cultural history at ICE since 2002. Educated in Grahamstown, Salzburg, Rome and Jerusalem, he is a member of Trinity College (Cambridge), the Meyerbeer Institute Schloss Thurmau (University of Bayreuth), the Salzburg Centre for Research in the Early English Novel (University of Salzburg) and the Maryvale Institute (Birmingham) as well as a panel tutor at ICE. Robert's publications number over 100 items, including books and articles on the late seventeenth-, eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century novel (particularly the Gothic Novel and Sir Walter Scott), the Bible, and European culture. He has specialized in the Romantic opera, especially the work of Giacomo Meyerbeer (a four-volume English edition of his diaries, critical studies, and two analyses of the operas), the opera-comique and Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Operetta, the Romantic Ballet and Ludwig Minkus. He has also worked with the BBC, the Royal Opera House, Naxos International and Marston Records, in the researching and preparation of productions. University of Cambridge Institute of Continuing Education, Madingley Hall, Cambridge, CB23 8AQ www.ice.cam.ac.uk Course programme Friday Please plan to arrive between 16:30 and 18:30. -

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini

La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène DU 15 AU 28 OCTOBRE 2013 6 REPRESENTATIONS Théâtre des Champs-Elysées SERVICE DE PRESSE +33 1 49 52 50 70 theatrechampselysees.fr La Caisse des Dépôts soutient l’ensemble de la RESERVATIONS programmation du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées T. +33 1 49 52 50 50 theatrechampselysees.fr Spontini 5 La Vestale La Vestale Gaspare Spontini NOUVELLE PRODUCTION Jérémie Rhorer direction Eric Lacascade mise en scène Emmanuel Clolus décors Marguerite Bordat costumes Philippe Berthomé lumières Daria Lippi dramaturgie Ermonela Jaho Julia Andrew Richards Licinius Béatrice Uria-Monzon La Grande Vestale Jean-François Borras Cinna Konstantin Gorny Le Souverain Pontife Le Cercle de l’Harmonie Chœur Aedes 160 ans après sa dernière représentation à Paris, le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées présente une nouvelle production de La Vestale de Gaspare Spontini. Spectacle en français Durée de l’ouvrage 2h10 environ Coproduction Théâtre des Champs-Elysées / Théâtre de la Monnaie, Bruxelles MARDI 15, VENDREDI 18, MERCREDI 23, VENDREDI 25, LUNDI 28 OCTOBRE 2013 19 HEURES 30 DIMANCHE 20 OCTOBRE 2013 17 HEURES SERVICE DE PRESSE Aude Haller-Bismuth +33 1 49 52 50 70 / +33 6 48 37 00 93 [email protected] www.theatrechampselysees.fr/presse Spontini 6 Dossier de presse - La Vestale 7 La Vestale La nouvelle production du Théâtre des Champs-Elysées La Vestale n’a pas été représentée à Paris en version scénique depuis 1854. On doit donner encore La Vestale... que je l’entende une seconde fois !... Quelle Le Théâtre des Champs-Elysées a choisi, pour cette nouvelle production, de œuvre ! comme l’amour y est peint !.. -

Marschner Heinrich

MARSCHNER HEINRICH Compositore tedesco (Zittau, 16 agosto 1795 – Hannover, 16 dicembre 1861) 1 Annoverato fra i maggiori compositori europei della sua epoca, nonché degno rivale in campo operistico di Carl Maria von Weber, strinse amicizia con i maggiori musicisti del tempo, fra cui Ludwig van Beethoven e Felix Mendelssohn Bartoldy. Dopo gli studi fatti a Lipsia ed a Praga con Tomášek e dopo essersi introdotto nel mondo musicale viennese, fu nominato maestro di cappella a Bratislava e successivamente divenne il direttore dei teatri dell'opera di Dresda e Lipsia; fu quindi ad Hannover nel periodo 1830-59, per dirigere la cappella di corte. Marschner fu fondamentalmente un compositore teatrale, fra le opere che gli conferirono maggior fama si annoverano: Der Vampyr (1828), Der templar und die Jüdin (1829) e un'opera di gusto popolare e leggendario, come è nel suo stile, intitolata Hans Heiling (1833), la quale ha alcune analogie con L'olandese volante di Richard Wagner. Caratteristica dell'arte di Marschner sono: la ricerca (nel melodramma) di soggetti soprannaturali caratteristici di quel senso puramente romantico di "orrore dilettevole", ma anche cavallereschi e soprattutto popolari, resi attraverso una ritmica incalzante, una vasta coloritura dei timbri orchestrali e con l'ausilio di numerosi leitmotiv e fili conduttori musicali. Non mancano inoltre nella sua produzione numerosi Lieder, due quartetti per pianoforte e ben sette trii per pianoforte particolarmente apprezzati da Robert Schumann. 2 3 HANS HEILING Tipo: Opera romantica in un prologo e tre atti Soggetto: libretto di Philipp Eduard Devrient Prima: Berlino, Königliches Opernhaus, 24 maggio 1833 Cast: la regina degli spiriti (S), Hans Heiling (Bar), Anna (S), Gertrude (A), Konrad (T), Stephan (B), Niklas (rec); spiriti, contadini, invitati, giocatori, tiratori Autore: Heinrich Marschner (1795-1861) Il personaggio di Hans Heiling, tra quelli creati da Marschner, rappresenta una delle più notevoli incarnazioni del tipico tema romantico dell’io diviso, condannato a non trovare la propria unità. -

The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington

English 345 ~ English Romanticism: The Power of the Imagination~ Fall 2012 Division of Humanities—English University of Maine at Farmington Instructor: Dr. Misty Krueger Office: 216A Roberts Learning Center Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays from 10 a.m.-11 a.m. and 2:30 p.m.-3:30 p.m. Office Phone: 207-778-7473 E-mail: [email protected] (preferred method of contact) COURSE DESCRIPTION Welcome to this course, which will cover the English Romantic period (1785-1832). Notable writers from this period include Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen, William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, the Shelleys, and John Keats, among many others. In this course we will explore how their works react to important contemporary political events, reconstruct a gothic past, draw on the supernatural, and incorporate spontaneity and imagination. Our specific goal in this course is to study how the ‘powers of the imagination’ lead some of the most well-known Romantic authors to craft brilliant and inventive essays, fiction, poetry, and dramatic literature. As such, we will spend our time examining these authors’ inspirations for writing, means of composition, and conceptions of the purpose of literature, as well as its effects on the individual and society-at-large. We are about to study some of the most beautiful literature ever written in the English language. Get ready to be inspired! Get ready to become an enthusiastic, active participant in this course by contributing discussion questions about our readings, completing reading responses, giving a formal class presentation on scholarly criticism, and conversing informally with your classmates about our course materials. -

Rosemary Ellen Guiley

vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page i The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS vamps_fm[fof]_final pass 2/2/09 10:06 AM Page ii The Encyclopedia of VAMPIRES, WEREWOLVES, and OTHER MONSTERS Rosemary Ellen Guiley FOREWORD BY Jeanne Keyes Youngson, President and Founder of the Vampire Empire The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves, and Other Monsters Copyright © 2005 by Visionary Living, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Guiley, Rosemary. The encyclopedia of vampires, werewolves, and other monsters / Rosemary Ellen Guiley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-4684-0 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4381-3001-9 (e-book) 1. Vampires—Encyclopedias. 2. Werewolves—Encyclopedias. 3. Monsters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF1556.G86 2004 133.4’23—dc22 2003026592 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro Spirituals for Solo Vocalist Compiled by Randye Jones This is a sample of recordings recommended for enhancing library collections of Spirituals and, thus, is limited (with one exception) to recordings available on compact disc. This list includes a variety of voice types, time periods, interpretative styles, and accompaniment. Selections were compiled from The Spirituals Database, a resource referencing more than 450 recordings of Negro Spiritual art songs. Marian Anderson, Contralto He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands (1994) RCA Victor 09026-61960-2 CD, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, Hamilton Forrest, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, Roland Hayes Spirituals (1999) RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-63306-2 CD, recorded between 1936 and 1952, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, John C. Payne, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, Hamilton Forrest, Robert MacGimsey, Roland Hayes, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, R. Nathaniel Dett Angela Brown, Soprano Mosiac: a collection of African-American spirituals with piano and guitar (2004) Albany Records TROY721 CD, variously with piano, guitar Songs by Angela Brown, Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Betty Jackson King, Roland Hayes, Joseph Joubert Todd Duncan, Baritone Negro Spirituals (1952) Allegro ALG3022 LP, with piano Songs by J. Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, William C. Hellman, Edward Boatner Denyce Graves, Mezzo-soprano Angels Watching Over Me (1997) NPR Classics CD 0006 CD, variously with piano, chorus, a cappella Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Marvin Mills, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Shelton Becton, Roland Hayes, Robert MacGimsey Roland Hayes, Tenor Favorite Spirituals (1995) Vanguard Classics OVC 6022 CD, with piano Songs by Roland Hayes Barbara Hendricks, Soprano Give Me Jesus (1998) EMI Classics 7243 5 56788 2 9 CD, variously with chorus, a cappella Songs by Moses Hogan, Roland Hayes, Edward Boatner, Harry T.