A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Hamblin History'

presents: JACOB HAMBLIN: HIS OWN STORY Hartt Wixom 7 November, 1998 Dixie College with Support from the Obert C. TannerFoundation When I began researching some 15 years ago to write a biography of Jacob Hamblin, I sought to separate the man from many myths and legends. I sought primary sources, written in his own hand, but initially found mostly secondary references. From the latter I knew Hamblin had been labeled by some high officials in the hierarchy of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as the "Mormon Apostle to the Lamanites" (Book of Mormon name for the American Indian). I also found an insightful autobiography edited by James A. Little, first published in 1887, but unfortunately concluding some ten years before Hamblin died. Thus, I began seeking primary sources, words written with Jacob Hamblin's own pen. I was informed by Mark Hamblin, Kanab, a great- great-grandson of Jacob, that a relative had a copy of an original diary. Family tradition had it that this diary was found in a welltraveled saddle bag, years after Jacob died These records, among others, provide precious understanding today into the life of a man who dared to humbly believe in a cause greater than himself-- and did more than pay lip service to it. His belief was that the Book of Mormon, published by the LDS Church in 1830, made promises to the Lamanites by which they might live up to the teachings of Jesus Christ, as had their forefathers, and receive the same spiritual blessings. Jacob firmly believed he might in so doing, also broker a peace between white and red man which could spare military warfare and bloodshed on the frontier of southern Utah and northern Arizona in the middle and late 1800s. -

Rentmeister Book Collection

Rentmeister Book Collection Contents Utah 2 Geology; Land Use ..................................................................................... 2 History ........................................................................................................ 2 Miscellaneous ............................................................................................. 7 County, Local, and Regional Utah Histories, Guidebooks, etc. ................. 8 Native Americans 17 The West 22 General ...................................................................................................... 22 Arizona ..................................................................................................... 32 California .................................................................................................. 32 Idaho ......................................................................................................... 34 Montana .................................................................................................... 34 Nevada ...................................................................................................... 35 New Mexico ............................................................................................. 35 Wyoming .................................................................................................. 35 The West (Time-Life Books Series) ........................................................ 36 Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints 39 Bibliography ............................................................................................ -

Journal of Mormon History Vol. 33, No. 2, 2007

Journal of Mormon History Volume 33 Issue 2 Article 1 2007 Journal of Mormon History Vol. 33, No. 2, 2007 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation (2007) "Journal of Mormon History Vol. 33, No. 2, 2007," Journal of Mormon History: Vol. 33 : Iss. 2 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/mormonhistory/vol33/iss2/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Mormon History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Mormon History Vol. 33, No. 2, 2007 Table of Contents CONTENTS ARTICLES • --The Reed Smoot Hearings: A Quest for Legitimacy Harvard S. Heath, 1 • --Senator George Sutherland: Reed Smoot’s Defender Michael Harold Paulos, 81 • --Daniel S. Tuttle: Utah’s Pioneer Episcopal Bishop Frederick Quinn, 119 • --Civilizing the Ragged Edge: Jacob Hamblin’s Wives Todd Compton, 155 • --Dr. George B. Sanderson: Nemesis of the Mormon Battalion Sherman L. Fleek, 199 REVIEWS --Peter Crawley, A Descriptive Bibliography of the Mormon Church. Volume Two: 1848–1852 Curt A. Bench, 224 --Sally Denton, Faith and Betrayal: A Pioneer Woman’s Passage in the American West Jeffery Ogden Johnson, 226 --Donald Q. Cannon, Arnold K. Garr, and Bruce A. Van Orden, eds., Regional Studies in Latter-day Saint History: The New England States Shannon P. Flynn, 234 --Wayne L. Cowdrey, Howard A. Davis, and Arthur Vanick, Who Really Wrote the Book of Mormon? The Spalding Enigma Robert D. -

The Life of Edward Partridge (1793-1840), the First Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2009-11-20 Fact, Fiction and Family Tradition: The Life of Edward Partridge (1793-1840), The First Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Sherilyn Farnes Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Farnes, Sherilyn, "Fact, Fiction and Family Tradition: The Life of Edward Partridge (1793-1840), The First Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints" (2009). Theses and Dissertations. 2302. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fact, Fiction and Family Tradition: The Life of Edward Partridge (1793-1840), The First Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Sherilyn Farnes A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Susan Sessions Rugh, Chair Jenny Hale Pulsipher Steven C. Harper Department of History Brigham Young University December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Sherilyn Farnes All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Fact, Fiction and Family Tradition: The Life of Edward Partridge (1793-1840), The First Bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Sherilyn Farnes Department of History Master of Arts Edward Partridge (1793-1840) became the first bishop of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1831, two months after joining the church. -

Jacob Vernon Hamblin

JACOB VERNON HAMBLIN Jacob Vernon Hamblin was born April 2, 1819 in Salem Ohio. His parents were Isaiah and Daphne Haynes Hamblin. He had a normal childhood with a family that was religious and studied the bible. He grew to a lean six feet tall. He married Lucinda Taylor in the autum of 1839. Jacob learned about the gospel from Elder Lyman Stoddard. He was baptized March 3, 1842 much to the chagrin of his wife, family and neighbors. My wife, Brigid, is from Michigan and in 1981 she joined the Church. One of the missionaries who baptized and confirmed her was Elder Gary Stoddard from Idaho. The Stoddard family blessed my life twice. Jacob's father-in-law took great pains to insult and abuse him. Jacob told him "you won't have the privilege of abusing me much longer". A few days later he took sick and he died. Later Lucinda asked Jacob "why don't you pray with me and our family?" Jacob stated "I don't like to pray before non-believers." Lucinda explained that her father appeared to her in a dream and said not to oppose Jacob any longer. She was baptized soon after. Jacob's father Isaiah Hamblin was very ill with spotted fever and near death when Jacob felt prompted to stop by. Jacob prayed for him and from that moment on, the fever broke and Isaiah was healed. Later, his 18 year old brother, Obed, was sick and near death and Jacob gave him a priesthood blessing and he was healed. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

Another Look at Joseph Smith's First Vision

SECTION TITLE Another Look at Joseph Smith’s First Vision Stan Larson The First Vision, that seminal event which has inspired and intrigued all of us for nearly two centuries, came into sharp focus again in 2012 when another volume of the prestigious Joseph Smith Papers was published. Highlighting the volume is the earliest known description of what transpired during the “boy’s frst uttered prayer”1 near his home in Palmyra in 1820. The narrative was written by Joseph Smith with his own pen in a ledger book in 1832. It is printed in the Papers volume under the title “History, Circa Summer 1832” and is especially interesting because the account was suppressed for about three decades. In the following transcription of the 1832 account, Joseph Smith’s words, spelling, and punctuation are retained and the entire block quote of the 1832 account is printed in bold (fol- lowing the lead of the Joseph Smith Papers printing): At about the the age of twelve years my mind become seriously imprest with regard to the all importent con- cerns of for the wellfare of my immortal Soul which led me to searching the scriptures believeing as I was taught, that they contained the word of God thus apply- ing myself to them and my intimate acquaintance with those of differant denominations led me to marvel excedingly for I discovered that <they did not adorn> instead of adorning their profession by a holy walk and Godly conversation agreeable to what I found contained in that sacred depository this was a grief to my Soul thus from the age of twelve years to ffteen I pondered many things in my heart concerning the sittuation of the world 37 38 DIALOGUE: A JOURNAL OF MORMON THOUGHT, 47, no. -

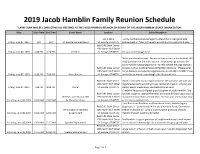

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS at the JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION on BEHALF of the JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS AT THE JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION ON BEHALF OF THE JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION. Date Start Time End Time Event Name Location Event Description 250 E 400 S Family members are encouraged to attend the St. George temple Friday, June 07, 2019 N/A N/A St. George Temple (Open) St. George, UT 84770 before check-in if they arrive early enough and are willing and able. Red Cliffs Stake Center 1285 North Bluff Street Friday, June 07, 2019 6:00 PM 6:20 PM Check-in St. George, UT 84770 Get your name badges here Bid on your favorite items. Donate an item or two to the Auction! We need donations for the silent auction. All proceeds go towards the Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization to help achieve the organization's Red Cliffs Stake Center mission, such as building the Jacob Hamblin Memorial. (Please email 1285 North Bluff Street Sonya Watkins, [email protected], or call 480-229-8082 if you Friday, June 07, 2019 6:30 PM 7:30 PM Silent Auction St. George, UT 84770 would like to donate something to the silent auction.) Red Cliffs Stake Center Dinner is included in your registration fee. Be sure you have paid and 1285 North Bluff Street registered properly according to our records at check-in. (If you have Friday, June 07, 2019 7:00 PM 8:30 PM Dinner St. George, UT 84770 dietary needs, please email [email protected]) Chevonne Pease is a 3rd great grand daughter of Jacob Hamblin. -

Book Reviews 193

Book Reviews 193 Book Reviews PATRICK Q. MASON, The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormon- ism in the Postbellum South. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, xi + 252 pp., charts, photographs, index, $29.95 hardback.) Reviewed by Beth Barton Schweiger Patrick Q. Mason has written an impor- tant book that cracks open a fresh topic for historians, who have barely touched the subject of Mormon missions in the South, much less the difficult question of anti- Mormon violence. Yet Mason’s ambitions reach beyond the region; he intends his book, which is “less about the experience of Mormons in the South than the reaction of southerners to their presence” (11), as a case study that will illuminate the vexing question of religious violence in American history and beyond. The signal contribution of the book is to recover the story of the Mormon missions in the Southern States. For this, Mason relies mainly on the Southern States Mission Manuscript History in the LDS Archives in Salt Lake City, which has languished virtually untouched by scholars. The manuscript offers a wealth of sources, including newspaper clippings, diaries, letters, and photographs which document in detail the numbers of missionaries and geographical reach of the missions, and accounts of anti-Mormon violence from eye-witnesses. Mason’s work focuses on the roughly the half century between 1852 and 1904—the period when Mormons openly practiced plural marriage. Mormon missions in the Southern States began soon after Mormonism’s founding in 1830 and encompassed the region. Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia were the focus of the work, but missionaries also worked in the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. -

PIPE Sprlnli Nafional Monumenl ARIZONA Pipe Spring National Monument

Old Mormon Fort PIPE SPRlnli nafional monumenl ARIZONA Pipe Spring national monument United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary National Park Service. Newton B. Drury. Director The buildings at Pipe Spring National opment of this part of the Southwest. Monument, constructed by the Mormons Under the leadership of Brigham during 1869-1870,and later used by pri- Young, they were able to establish their vate interests as a ranch headquarters culture in this land where many others and cattle buying and shipping point, failed. As an expression of the fore- represent an important phase of the sight, courage, vigor, persistence, and movement westward by the American faith of the pioneer, and of the Mormons pioneer. The Mormons who settled at in particular, Pipe Spring is preserved Pipe Spring and other similar areas can as a monument, not only to those who be given much of the credit for the settled the Southwest but to all who took exploration, colonization, and devel- part in the Westward Movement. Interior Courtyard Pipe Spring is within a general area paces. Hamblin did fail to puncture of tremendous geological interest, a the handkerchief; because the silk cloth, stratigraphic section extending 100 miles hung by the upper edge only, yielded The Natural Setting from north to south. This is from the Pipe Spring Is Named before the force of the bullet. Grand Canyon of the Colorado, where Hamblin, somewhat vexed, turned to Pipe Spring is in the southwestern part the old original basic rocks of the earth The first white men to visit Pipe Spring one of the men, daring him to put his of the Colorado Plateau, at an elevation are exposed, to the relatively new and were the Jacob Hamblin party, who, in pipe on a rock near the spring, which of approximately 5,000 feet above sea- recent beds (only about 60 million years 1856, camped at this then nameless was at some distance, so that the mouth level. -

Drought and the Mountain Meadows Massacre Dillon

Hell in the Promised Land: Drought and the Mountain Meadows Massacre Dillon Maxwell HIST 539: World Environmental History 5/7/2018 1 From September 7 to 11, 1857, hell came to the Promised Land. Between those days Mormon militiamen and several Paiute Native Americans attacked a wagon train leaving no survivors. On September 12, 120 bodies of men, women, and children lay bloody and lifeless, baking under the Utah sun. The gruesome scene spread across the valley of Mountain Meadows, Utah. The Baker-Fancher Party met their fate. A month earlier in August of 1857, the Baker-Fancher party stopped in Salt Lake City en- route to California to resupply their caravan. In Salt Lake City, the party decided to turn south to follow the Old Spanish Trail through Nevada. On September 7, they reached Mountain Meadows, a famous stop for migrants in southwestern Utah. Mountain Meadows hosted streams, springs, and rolling pastureland; a fine place for a large wagon train to make camp for a few days before making the trek across the deserts of Nevada. The event that took place in mid-September, 1857 became known as the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon militiamen from Iron County killed 120 members of the Baker-Fancher party, sparing the lives of several small children. Different perspectives offer different reasons as to what drove the Mormon Militia to attack the passing emigrants. Rising tensions between the US Government and Mormons, radicalized Mormon preaching against non-believers, and suspicion that the party of emigrants committed offensive acts to the Mormons settlers all factor into event. -

Download a Printable PDF File of the Selected Chapter

(The Improvement Era , December 1948) Chapter 3 In the year 1851, President Brigham Young sent a colony to build a fort and establish a place called Parowan, thus extending the great Mormon expansion to the south, encouraged at first by the Ute Chief Walker. But as the thin line of forts began to reach farther and farther into Chief Walker's territory, he viewed this influx with alarm and incited his people to attack. Among the Mormons were those who genuinely loved the Indians and made constant appeals to them. Foremost in this number were Jacob Hamblin and Thales Haskell. Added to the hostility of the Utes were three other adversaries: the Navajos the renegade whites, and nature, which seemed at times the greatest adversary of all. In cold blood an Indian had shot George A. Smith with his own gun which the Indian had borrowed, and Jacob Hamblin-and his company had been forced to go on and leave his body. The plunderers followed Hamblin's trail homeward and raided the herds of the weary settlers. No treaty with the United States could guarantee settlers from the depredations of the Navajos. However profitable the Utah field was proving to be, the beaten trails of the Navajo to the southeast were still too inviting and too rich in yield to forsake because of the undeveloped prospects on the northwest. From these trails to the southeast they brought home crops, livestock, children, women. All the promises they had made to refrain from this practice meant nothing to them. It was a rich industry; nothing but force could ever pry them out of it.