Jacob Hamblin in Tooele

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Hamblin History'

presents: JACOB HAMBLIN: HIS OWN STORY Hartt Wixom 7 November, 1998 Dixie College with Support from the Obert C. TannerFoundation When I began researching some 15 years ago to write a biography of Jacob Hamblin, I sought to separate the man from many myths and legends. I sought primary sources, written in his own hand, but initially found mostly secondary references. From the latter I knew Hamblin had been labeled by some high officials in the hierarchy of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as the "Mormon Apostle to the Lamanites" (Book of Mormon name for the American Indian). I also found an insightful autobiography edited by James A. Little, first published in 1887, but unfortunately concluding some ten years before Hamblin died. Thus, I began seeking primary sources, words written with Jacob Hamblin's own pen. I was informed by Mark Hamblin, Kanab, a great- great-grandson of Jacob, that a relative had a copy of an original diary. Family tradition had it that this diary was found in a welltraveled saddle bag, years after Jacob died These records, among others, provide precious understanding today into the life of a man who dared to humbly believe in a cause greater than himself-- and did more than pay lip service to it. His belief was that the Book of Mormon, published by the LDS Church in 1830, made promises to the Lamanites by which they might live up to the teachings of Jesus Christ, as had their forefathers, and receive the same spiritual blessings. Jacob firmly believed he might in so doing, also broker a peace between white and red man which could spare military warfare and bloodshed on the frontier of southern Utah and northern Arizona in the middle and late 1800s. -

The Legend of Porter Rockwell

Reviews/115 THE L E G E N D OF P O R T E R ROCKWELL Gustive O. Larson Orrin Porter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder. By Harold Schindler. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1966. Pp. 399. Gustive Larson is Associate Professor of Religion and History at Brigham Young University and the author of many books and articles on Utah and the Mormons. He is presently working on the anti-polygamy crusade. The sketches in this review are taken from this exceptionally handsome volume. The artist is Dale Bryner. The history of Mormonism and of early Utah as the two merge after 1847 has customarily featured ecclesiastical and political leaders, leaving others who played significant roles on the fighting front of westward expansion to lurk in historical shadows. Among many such neglected men were Ste- phen Markham, Ephraim Hanks, Howard Egan, and Orrin Porter Rock- well. Of the last much has been writ- ten but, like the vines which cover the sturdy tree, legend has entwined itself so intricately in Rockwell literature as to create a challenging enigma. This challenge has been accepted by Har- old Schindler in his book, Orrin Por- ter Rockwell: Man of God, Son of Thunder. The result has been to bring the rugged gun-man more definitely into view but with much of the legendary still clinging to him. An impressive bibliography reflects thorough research on the part of the author, and absence of discrimination between Mormon and Gentile sources indicates a conscientious effort to be objective. Yet the reader raises an intel- lectual eyebrow when confronted with an over-abundance of irresponsible "testimony" and sensationalism represented by such names as William Daniels, Bill Hickman, Joseph H. -

A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 53 | Issue 3 Article 15 9-1-2014 A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M. Compton Jay H. Buckley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Compton, Todd M. and Buckley, Jay H. (2014) "A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 53 : Iss. 3 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol53/iss3/15 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Compton and Buckley: A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M. Compton. A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2013. Reviewed by Jay H. Buckley acob Hamblin embodies one of the more colorful and interesting Mor- Jmon pioneers in Utah Territory during the second half of the nineteenth century. During his long and eventful life, he wore many hats—explorer, frontiersman, Indian agent, missionary, colonizer, community leader— and wore them well. Born on April 6, 1819, on the Ohio frontier, Hamblin left the family farm at age nineteen to strike out on his own. After nearly dying during a cave-in at a lead mine in Galena, Illinois, he collected his wages and traveled to Wisconsin to homestead. In 1839, he married Lucinda Taylor and began farming and raising a family. -

Jacob Vernon Hamblin

JACOB VERNON HAMBLIN Jacob Vernon Hamblin was born April 2, 1819 in Salem Ohio. His parents were Isaiah and Daphne Haynes Hamblin. He had a normal childhood with a family that was religious and studied the bible. He grew to a lean six feet tall. He married Lucinda Taylor in the autum of 1839. Jacob learned about the gospel from Elder Lyman Stoddard. He was baptized March 3, 1842 much to the chagrin of his wife, family and neighbors. My wife, Brigid, is from Michigan and in 1981 she joined the Church. One of the missionaries who baptized and confirmed her was Elder Gary Stoddard from Idaho. The Stoddard family blessed my life twice. Jacob's father-in-law took great pains to insult and abuse him. Jacob told him "you won't have the privilege of abusing me much longer". A few days later he took sick and he died. Later Lucinda asked Jacob "why don't you pray with me and our family?" Jacob stated "I don't like to pray before non-believers." Lucinda explained that her father appeared to her in a dream and said not to oppose Jacob any longer. She was baptized soon after. Jacob's father Isaiah Hamblin was very ill with spotted fever and near death when Jacob felt prompted to stop by. Jacob prayed for him and from that moment on, the fever broke and Isaiah was healed. Later, his 18 year old brother, Obed, was sick and near death and Jacob gave him a priesthood blessing and he was healed. -

The Boggs Shooting and Attempted Extradition: Joseph Smith’S Most Famous Case Morris A

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 48 | Issue 1 Article 2 1-1-2009 The Boggs Shooting and Attempted Extradition: Joseph Smith’s Most Famous Case Morris A. Thurston Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Thurston, Morris A. (2009) "The Boggs Shooting and Attempted Extradition: Joseph Smith’s Most Famous Case," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 48 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol48/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Thurston: The Boggs Shooting and Attempted Extradition: Joseph Smith’s Most Nineteenth-century lithograph of the Tinsley Building in Springfield, Illinois, where proceedings in Joseph Smith’s extradition case took place in January 1843. The courtroom was located in rented facilities on the second floor. In August 1843, Abraham Lincoln and Stephen T. Logan moved their law practice to the third floor of the Tinsley Building. Published by BYU ScholarsArchive, 2009 1 BYU Studies Quarterly, Vol. 48, Iss. 1 [2009], Art. 2 The Boggs Shooting and Attempted Extradition Joseph Smith’s Most Famous Case Morris A. Thurston hen the Mormons were driven out of Missouri during the winter of W1838–39, they found the people of Illinois to have sympathetic hearts and welcoming arms. The Quincy Whig noted that the Mormons “appear, so far as we have seen, to be a mild, inoffensive people, who could not have given a cause for the persecution they have met with.” TheAlton Telegraph declared that in Missouri’s treatment of the Mormons “every principle of law, justice, and humanity, [had] been grossly outraged.”1 Over the next six years, however, feelings toward the Mormons gradually deteriorated, newspaper sentiment outside Nauvoo turned stridently negative, and in June 1844 their prophet was murdered by an enraged mob. -

Polygamy and Mormon Church Leaders Alpheus Cutler February 29, 1784

Polygamy and Mormon Church Leaders Alpheus Cutler February 29, 1784 – June 10, 1864 “It is no exaggeration to say that Cutler, next to the apostles, was one of Mormonism's most important leaders during this period.” – Journal of Mormon History, “Conflict in the Camps of Israel,” DANNY L. JORGENSEN, p. 31 1808 One thing to keep in mind when it comes to this family and others in early Mormonism is everyone involved is either married to, or a blood relative of each other. It’s almost impossible to extract definitive information on who fathered whom, or making sense of how they know each other. To complicate matters further, some have lied about a father’s identity by using pseudonyms, even to their own children. Our story about Alpheus picks up in 1808 with his first marriage, as records of Cutler’s life before that time are sparse. He met and married Lois Lathrop (distant cousin of Joseph Smith) while living in New Hampshire. Several years into their marriage they moved to western New York, where he and his family listened to a sermon by David Patten and Reynolds Cahoon. 1833 Following Patten’s sermon, they asked him to pray for their ailing daughter, Lois, and according to journals after laying hands on her, she was cured. (There are also stories of the daughter, 21 yrs old, making the request they lay hands on her). Not long after she was temporarily healed from TB, the family quickly joined the Church and moved to Kirtland sometime between 1833-1834. She ended up dying about 4-5 yrs later. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

Early Marriages Performed by the Latter-Day Saint Elders in Jackson County, Missouri, 1832-1834

Scott H. Faulring: Jackson County Marriages by LDS Elders 197 Early Marriages Performed by the Latter-day Saint Elders in Jackson County, Missouri, 1832-1834 Compiled and Edited with an Introduction by Scott H. Faulring During the two and a half years (1831-1833) the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints lived in Jackson County, Missouri, they struggled to establish a Zion community. In July 1831, the Saints were commanded by revelation to gather to Jackson County because the Lord had declared that this area was “the land of promise” and designat- ed it as “the place for the city of Zion” (D&C 57:2). During this period, the Mormon settlers had problems with their immediate Missourian neighbors. Much of the friction resulted from their religious, social, cultural and eco- nomic differences. The Latter-day Saint immigrants were predominantly from the northeastern United States while the “old settlers” had moved to Missouri from the southern states and were slave holders. Because of the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Missouri was a slave state. Eventually, by mid-July 1833, a militant group of Jackson County Missourians became intolerant of the Mormons and began the process of forcefully expelling them from the county.1 And yet in spite of these mounting hostilities, a little-known aspect of the Latter-day Saints’ stay in Jackson County is that during this time, the Mormon elders were allowed to perform civil marriages. In contrast to the legal difficulties some of the elders faced in Ohio, the Latter-day Saint priest- hood holders were recognized by the civil authorities as “preachers of the gospel.”2 Years earlier, on 4 July 1825, Missouri enacted a statute entitled, “Marriages. -

Orrin Porter Rockwell

Heroes and Heroines: Orrin Porter Rockwell By Lawrence Cummins Lawrence Cummins, “Orrin Porter Rockwell,” Friend, May 1984, 42 Listening to the Prophet Joseph Smith tell the story of the angel and the hidden plates, young Porter Rockwell’s adventurous nature was stirred. The Smiths and Rockwells, frontier neighbors in Manchester, New York, often visited each other. Although Porter was eight years younger than the Prophet, a bond of friendship between the two was quickly formed. Later, when Joseph needed money to publish The Book of Mormon, Porter picked berries by moonlight—after his chores were done—and sold them. When there were no berries to pick, he gathered wood and hauled it to town to sell. The money he earned was given to the Prophet. The two families remained loyal to each other, and when the Smiths moved to Fayette, New York, the Rockwells followed. Sixteenyearold Porter was probably the youngest member of the first group to be baptized into the Church, after it was organized in 1830. When the Fayette Branch of the Church moved to Kirtland, Ohio, Porter went with them. However, his stay there was short. Porter was sent with the first group of Saints to Jackson County, Missouri, the intended central gathering place for members of the Church. The elders often met at Porter’s home to discuss ways of protecting the Saints from the lawless Missouri mobs who were persecuting them. While he was in Missouri, Porter became a crack marksman with a gun. And he made several trips to Liberty Jail to take food and comfort to Joseph Smith and his counselors when they had been illegally jailed. -

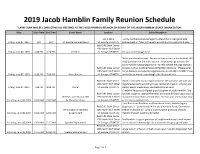

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS at the JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION on BEHALF of the JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS AT THE JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION ON BEHALF OF THE JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION. Date Start Time End Time Event Name Location Event Description 250 E 400 S Family members are encouraged to attend the St. George temple Friday, June 07, 2019 N/A N/A St. George Temple (Open) St. George, UT 84770 before check-in if they arrive early enough and are willing and able. Red Cliffs Stake Center 1285 North Bluff Street Friday, June 07, 2019 6:00 PM 6:20 PM Check-in St. George, UT 84770 Get your name badges here Bid on your favorite items. Donate an item or two to the Auction! We need donations for the silent auction. All proceeds go towards the Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization to help achieve the organization's Red Cliffs Stake Center mission, such as building the Jacob Hamblin Memorial. (Please email 1285 North Bluff Street Sonya Watkins, [email protected], or call 480-229-8082 if you Friday, June 07, 2019 6:30 PM 7:30 PM Silent Auction St. George, UT 84770 would like to donate something to the silent auction.) Red Cliffs Stake Center Dinner is included in your registration fee. Be sure you have paid and 1285 North Bluff Street registered properly according to our records at check-in. (If you have Friday, June 07, 2019 7:00 PM 8:30 PM Dinner St. George, UT 84770 dietary needs, please email [email protected]) Chevonne Pease is a 3rd great grand daughter of Jacob Hamblin. -

Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: an Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University

BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University Compiled by STANLEY B. KIMBALL 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 The Library SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Carbondale—Edwardsville Bibliographic Contributions No. 1 SOURCES OF MORMON HISTORY IN ILLINOIS, 1839-48 An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 Compiled by Stanley B. Kimball Central Publications Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois ©2014 Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, May, 1966 FOREWORD In the course of developing a book and manuscript collection and in providing reference service to students and faculty, a univeristy library frequently prepares special bibliographies, some of which may prove to be of more than local interest. The Bibliographic Contributions series, of which this is the first number, has been created as a means of sharing the results of such biblio graphic efforts with our colleagues in other universities. The contribu tions to this series will appear at irregular intervals, will vary widely in subject matter and in comprehensiveness, and will not necessarily follow a uniform bibliographic format. Because many of the contributions will be by-products of more extensive research or will be of a tentative nature, the series is presented in this format. Comments, additions, and corrections will be welcomed by the compilers. The author of the initial contribution in the series is Associate Professor of History of Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, Illinois. He has been engaged in research on the Nauvoo period of the Mormon Church since he came to the university in 1959 and has published numerous articles on this subject. -

Book Reviews 193

Book Reviews 193 Book Reviews PATRICK Q. MASON, The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormon- ism in the Postbellum South. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, xi + 252 pp., charts, photographs, index, $29.95 hardback.) Reviewed by Beth Barton Schweiger Patrick Q. Mason has written an impor- tant book that cracks open a fresh topic for historians, who have barely touched the subject of Mormon missions in the South, much less the difficult question of anti- Mormon violence. Yet Mason’s ambitions reach beyond the region; he intends his book, which is “less about the experience of Mormons in the South than the reaction of southerners to their presence” (11), as a case study that will illuminate the vexing question of religious violence in American history and beyond. The signal contribution of the book is to recover the story of the Mormon missions in the Southern States. For this, Mason relies mainly on the Southern States Mission Manuscript History in the LDS Archives in Salt Lake City, which has languished virtually untouched by scholars. The manuscript offers a wealth of sources, including newspaper clippings, diaries, letters, and photographs which document in detail the numbers of missionaries and geographical reach of the missions, and accounts of anti-Mormon violence from eye-witnesses. Mason’s work focuses on the roughly the half century between 1852 and 1904—the period when Mormons openly practiced plural marriage. Mormon missions in the Southern States began soon after Mormonism’s founding in 1830 and encompassed the region. Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia were the focus of the work, but missionaries also worked in the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi.