Book Reviews 193

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon-California Trails Association Convention Booklet

Oregon-California Trails Association Thirty-Sixth Annual Convention August 6 – 11, 2018 Convention Booklet Theme: Rails and Trails - Confluence and Impact at Utah’s Crossroads of the West \ 1 | P a g e Table of Contents Page 2 Invitation & Contact Info 3 Registration Information 4 Acknowledgement of Risk 5 Menu 7 Mail in Form 9 Schedule & Daily Events 11 Activity Stations/Displays 12 Speakers 14 Activity Station Presenters 16 Tour Guides 17 Pre-& Post-Convention Tour Descriptions 20 Convention Bus Tour Descriptions 22 Special Events 22 Book Room, Exhibits, & Authors Night 23 Accommodations (Hotels, RV sites) 24 State Parks 24 Places to Visit 26 Suggested Reading List, Sun & Altitude & Ogden-Eccles Conference Center Area Maps 2415 Washington Blvd. Ogden, Utah 84401 27-28 Convention Center Maps An Invitation to OCTA’s Thirty-Sixth Annual Convention On behalf of the Utah Crossroads Chapter, we invite you to the 2018 OCTA Convention at the Eccles Convention Center in Ogden, Utah. Northern Utah was in many ways a Crossroads long before the emigrants, settlers, railroad and military came here. As early as pre-Fremont Native Americans, we find evidence of trails and trade routes across this geographic area. The trappers and traders, both English and American, knew the area and crisscrossed it following many of the Native American trails. They also established new routes. Explorers sought additional routes to avoid natural barriers such as the mountains and the Great Salt Lake. As emigrants and settlers traveled west, knowledge of the area spread. The Crossroads designation was permanently established once the Railroad spanned the nation. -

Jacob Hamblin History'

presents: JACOB HAMBLIN: HIS OWN STORY Hartt Wixom 7 November, 1998 Dixie College with Support from the Obert C. TannerFoundation When I began researching some 15 years ago to write a biography of Jacob Hamblin, I sought to separate the man from many myths and legends. I sought primary sources, written in his own hand, but initially found mostly secondary references. From the latter I knew Hamblin had been labeled by some high officials in the hierarchy of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as the "Mormon Apostle to the Lamanites" (Book of Mormon name for the American Indian). I also found an insightful autobiography edited by James A. Little, first published in 1887, but unfortunately concluding some ten years before Hamblin died. Thus, I began seeking primary sources, words written with Jacob Hamblin's own pen. I was informed by Mark Hamblin, Kanab, a great- great-grandson of Jacob, that a relative had a copy of an original diary. Family tradition had it that this diary was found in a welltraveled saddle bag, years after Jacob died These records, among others, provide precious understanding today into the life of a man who dared to humbly believe in a cause greater than himself-- and did more than pay lip service to it. His belief was that the Book of Mormon, published by the LDS Church in 1830, made promises to the Lamanites by which they might live up to the teachings of Jesus Christ, as had their forefathers, and receive the same spiritual blessings. Jacob firmly believed he might in so doing, also broker a peace between white and red man which could spare military warfare and bloodshed on the frontier of southern Utah and northern Arizona in the middle and late 1800s. -

Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows

Book Reviews 149 Book Reviews WILL BAGLEY. Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002. xxiv + 493 pp. Illustrations, maps, appendix, notes, bibliography, index. $39.95 hardback.) Reviewed by W. Paul Reeve, assistant professor of history, Southern Virginia University, and Ardis E. Parshall, independent researcher, Orem, Utah. Explaining the violent slaughter of 120 men, women, and children at the hands of God-fearing Christian men—priesthood holders, no less, of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—is no easy task. Biases per- meate the sources and fill the historical record with contradictions and polemics. Untangling the twisted web of self-serving testimony, journals, memoirs, government reports, and the like requires skill, forthrightness, integrity, and the utmost devotion to established standards of historical scholarship. Will Bagley, a journalist and independent historian with sever- al books on Latter-day Saint history to his credit, has recently tried his hand at unraveling the tale. Even though Bagley claims to be aware of “the basic rules of the craft of history” (xvi), he consistently violates them in Blood of the Prophets. As a result, Juanita Brooks’ The Mountain Meadows Massacre remains the most definitive and balanced account to date. Certainly there is no justification for the Mountain Meadows Massacre. Mormon men along with Paiute allies acted beyond the bounds of reason to murder the Fancher party, a group of California-bound emigrants from Arkansas passing through Utah in 1857. It is a horrific crime, one that Bagley correctly identifies as “the most violent incident in the history of America’s overland trails” (xiii), and it belongs to Utah and the Mormons. -

Select Bibliography

select bibliography primary sources archives Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archive of the Archbishop of Mechelen), Brussels, Belgium. Archive at St. Anthony Convent and Motherhouse, Sisters of St. Francis, Syracuse, NY. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Honolulu. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Leuven, Belgium. Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. kalaupapa manuscripts and collections Bigler, Henry W. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cannon, George Q. Journals. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cluff, Harvey Harris. Autobiography. Handwritten copy. Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Decker, Daniel H. Mission Journal, 1949–1951. Courtesy of Daniel H. Decker. Farrer, William. Biographical Sketch, Hawaiian Mission Report, and Diary of William Farrer, 1946. Copied from the original and housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Gibson, Walter Murray. Diary. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Green, Ephraim. Diary. Microfilm copy, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Halvorsen, Jack L. Journal and correspondence. Copies in possession of the author. Hammond, Francis A. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hawaii Mission President’s Records, 1936–1964. LR 3695 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haycock, D. Arthur. Correspondence, 1954–1961. Courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle. “Incoming Letters of the Board of Health.” Hansen’s Disease. -

Blood Atonement and the Origin of Plural Marriage : a Discussion

hod Atonement and the \Origin of Plural Marriage A DISCUSSION Correspondence between ^DER JOSEPH F. SMITH, JR. the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints MR. RICHARD C. EVANS Second Counselor in the Presidency of the "Reorganized" Chiurch Blood Atonement and the Origin of Plural Marriage A DISCUSSION Correspondence between ELDER JOSEPH F. SMITH, JR. Of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints AND MR. RICHARD C. EVANS Second Counselor in the Presidency of the "Reorganized" Chiu*ch '" HAROLD B ' 8RIGHAM .NivEH^^rn PP _AH "To correct misrepresentation, we adopt self representation.' —John Taylor. Blood Atonement —AND THE Origin of Plural Marriage A DISCUSSION Correspondence between Elder Josfjph F. Smith, (Jr.,) of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and Mr. Richard C. Evans, second counselor (1905) in the Presidency of the "Reorganized" Church. A con- clusive refutation of the false charges persistently made by ministers of the "Reorganized" Church against the Latter- day Saints and their beUef. Also a supplement containing a number of affidavits and other matters bearing on the subjects. Press of Zion's Printing and Publishing Company Independence, Jackson County, Missouri. HAROLD B. LEE LfBRAR> 3RIGHAM YOUNG UNIVEr^' ' PROVO UTAH BLOOD ATONEMENT And the Origin of Plural Marriage INTRODUCTION The correspondence in this pamphlet was brought about through the wilful misrepresentation of the doctrines of the Latter-day Saints and the unwarranted abuse of the authori- ties of the Church by Mr. Richard C. Evans, in an interview which appeared in the Toronto (Canada) Daily Star of January 28, 1905. A copy of that interview was placed in the hands of the writer, who, on February 19th following, replied to Mr. -

A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M

BYU Studies Quarterly Volume 53 | Issue 3 Article 15 9-1-2014 A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M. Compton Jay H. Buckley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq Recommended Citation Compton, Todd M. and Buckley, Jay H. (2014) "A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary," BYU Studies Quarterly: Vol. 53 : Iss. 3 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol53/iss3/15 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Studies Quarterly by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Compton and Buckley: A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary Todd M. Compton. A Frontier Life: Jacob Hamblin, Explorer and Indian Missionary. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2013. Reviewed by Jay H. Buckley acob Hamblin embodies one of the more colorful and interesting Mor- Jmon pioneers in Utah Territory during the second half of the nineteenth century. During his long and eventful life, he wore many hats—explorer, frontiersman, Indian agent, missionary, colonizer, community leader— and wore them well. Born on April 6, 1819, on the Ohio frontier, Hamblin left the family farm at age nineteen to strike out on his own. After nearly dying during a cave-in at a lead mine in Galena, Illinois, he collected his wages and traveled to Wisconsin to homestead. In 1839, he married Lucinda Taylor and began farming and raising a family. -

Jacob Vernon Hamblin

JACOB VERNON HAMBLIN Jacob Vernon Hamblin was born April 2, 1819 in Salem Ohio. His parents were Isaiah and Daphne Haynes Hamblin. He had a normal childhood with a family that was religious and studied the bible. He grew to a lean six feet tall. He married Lucinda Taylor in the autum of 1839. Jacob learned about the gospel from Elder Lyman Stoddard. He was baptized March 3, 1842 much to the chagrin of his wife, family and neighbors. My wife, Brigid, is from Michigan and in 1981 she joined the Church. One of the missionaries who baptized and confirmed her was Elder Gary Stoddard from Idaho. The Stoddard family blessed my life twice. Jacob's father-in-law took great pains to insult and abuse him. Jacob told him "you won't have the privilege of abusing me much longer". A few days later he took sick and he died. Later Lucinda asked Jacob "why don't you pray with me and our family?" Jacob stated "I don't like to pray before non-believers." Lucinda explained that her father appeared to her in a dream and said not to oppose Jacob any longer. She was baptized soon after. Jacob's father Isaiah Hamblin was very ill with spotted fever and near death when Jacob felt prompted to stop by. Jacob prayed for him and from that moment on, the fever broke and Isaiah was healed. Later, his 18 year old brother, Obed, was sick and near death and Jacob gave him a priesthood blessing and he was healed. -

Utah: Connect with the Crossroads of the West Laurie Werner Castillo [email protected]

Utah: Connect with the Crossroads of the West Laurie Werner Castillo [email protected] 4 DIVISIONS of Utah History: Religious Colony, Supply station, Critical link to the West. 1 Ecclesiastical 24 Jul 1847 - 12 Mar 1849 LDS Church was the civil government also. 2 Provisional Government of the State of Deseret 13 Mar 1849 - 8 Sep 1850 3 Territory of Utah 9 Sep 1850 - 3 Jan 1896 4 State of Utah Jan 1896 - Present Most civil vital records date to this time period. I. Utah Geography & Jurisdictions - Search records for all that apply! 1847 Mexico-US Territorial Acquisitions - http://www.uintahbasintah.org/maps/usterritories.jpg 1849 Proposed State of Deseret - https://tinyurl.com/y96wm9ve 1850 Utah Territory Created - Included parts of future Nevada, Arizona, Colorado and Wyoming 1850-1868 Utah Territorial Evolution - https://tinyurl.com/y75k94zs Animated map -Territorial Losses 1852-1918 Chart of County Formation in Utah & Chart of Extinct Counties of Utah - For both see: UT State Archives https://archives.utah.gov/research/guides/county-formation.htm 1856 Utah Territory Map https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Utah_Territory_1856_map.png Contested Boundaries: Creating Utah State Lines https://history.utah.gov/connect/maps/ II. Getting Started: Locate Jurisdictions & Assess Record Availability A. Basics: Step 1 - Locate a map of the time period involved. List the potential jurisdictions. Step 2 - Utah State Archives - Guides, Digital Records & Indexes https://archives.utah.gov/ Step 3 - Assess holdings at FamilySearch www.familysearch.org & Ancestry www.Ancestry.com B. Things to Keep in Mind: 1. Territories were administered by the Federal government. They were led by Governors who were appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate. -

Make It an Indian Massacre:”

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By JOHN E. BAUCOM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 “MAKE IT AN INDIAN MASSACRE:” THE SCAPEGOATING OF THE SOUTHERN PAIUTES A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY ______________________________ Dr. R. Warren Metcalf, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Rachel Shelden ______________________________ Dr. Sterling Evans © Copyright by JOHN E. BAUCOM 2016 All Rights Reserved. To my encouraging study-buddy, Heather ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: First, I would like to thank the Mountain Meadows Monument Foundation. Specifically Dr. Burr Fancher, Diann Fancher, and Ron Wright. The MMMF is largely comprised of the descendants of the seventeen young children that survived the massacre. Their personal support and feedback have proven to be an invaluable resource. I wish them success in their continued efforts to honor the victims of the massacre and in their commitment to guarantee unrestricted access to the privately owned massacre site. I’m grateful for the MMMF’s courage and reverence for their ancestors, along with their efforts in bringing greater awareness to the Mountain Meadows Massacre. I must also acknowledge the many helpful archivists that I’ve met along the way. Their individual expertise, patience, and general support have greatly influenced this project. The Mountain Meadows Massacre is no trivial or unfamiliar topic in the quiet corridors of Utah’s archives. And rather than rolling their eyes at yet another ambitious inquiry into massacre, many were quick to point me in new directions. -

International Legal Experience and the Mormon Theology of the State, 1945–2012

E1_OMAN.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 12/15/2014 3:31 PM International Legal Experience and the Mormon Theology of the State, 1945–2012 Nathan B. Oman I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 715 II. THE INTERNATIONAL EXPANSION OF MORMONISM SINCE 1945 .. 719 A. PRE-1945 MORMON EXPANSION .............................................. 719 B. THE POST-WAR PERIOD ........................................................... 720 III. LEGAL CHALLENGES AND INTERNATIONAL EXPANSION ................ 723 A. LEGAL CHALLENGES FACED BY THE CHURCH ............................ 724 B. CAUSES OF THE CHURCH’S LEGAL CHALLENGES ........................ 730 IV. LAW AND THE MORMON THEOLOGY OF THE STATE ...................... 740 A. EARLIER MORMON THEOLOGIES OF THE STATE ........................ 742 B. A QUIETIST MORMON THEOLOGY OF THE STATE ...................... 744 V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................ 749 I. INTRODUCTION By spring 1945, the Third Reich had reached its Götterdämmerung. The previous summer, Allied Armies, under Dwight D. Eisenhower, landed in Normandy and began driving toward the Fatherland. The Red Army had been pushing west toward Berlin since its victory over the final German offensive at the Battle of Kursk in August 1943. On April 30, Hitler committed suicide in his bunker, and Germany surrendered seven days later. War continued on the other side of the globe. The American strategy of island-hopping had culminated in the 1944 recapture of the Philippines and the final destruction Professor of Law and Robert and Elizabeth Scott Research Professor, William & Mary Law School. I would like to thank Abigail Bennett, Jeffrey Bennett, Bob Bennett, Wilfried Decoo, Cole Durham, and Michael Homer for their assistance and comments. I also presented an earlier version of this paper at the 2014 International Religious Legal Theory Conference sponsored by the Center for the Study of Law and Religion at Emory Law School and benefited from participants’ comments. -

St. George Tabernacle, Photograph Courtesy Intellectual Reserve. Landon: the History of the St

St. George Tabernacle, photograph courtesy Intellectual Reserve. Landon: The History of the St. George Tabernacle 125 “A Shrine to the Whole Church”: The History of the St. George Tabernacle Michael N. Landon At least as early as 1862, Brigham Young directed Latter-day Saint lead- ers in St. George to construct a tabernacle, a building designed not only for church services, but which also would serve as a social and cultural center for the entire community. In a letter to Mormon Apostle Erastus Snow, Brigham Young clearly noted that the tabernacle would represent more than a place of worship: As I have already informed you, I wish you and the brethren to build, as speedily as possible, a good substantial, commodious, well finished meeting house, one large enough to comfortably seat at least 2000 persons and that will be not only useful but also an ornament to your city and a credit to your energy and enterprise. I hereby place at your disposal, expressly to aid in building the aforesaid meeting-house, the labor, molasses, vegetable and grain tithing of Cedar City and of all places and persons south of that city. I hope you will begin the building at the earliest practicable date; and be able with the aid herein given to speedily prosecute the work to completion.1 Brigham Young’s efforts to encourage Latter-day Saints to settle in St. George, indeed in all of southern Utah, had met with mixed results. Even George A. Smith, his longtime friend and counselor in the First Presidency, once described the area as “the most wretched, barren, God-forsaken country in the world.”2 In his letter to Snow, Brigham Young implied that a substantial meeting place would give the St. -

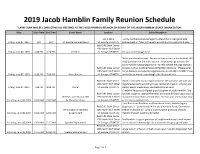

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS at the JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION on BEHALF of the JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION

2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion Schedule *LARRY BURK WILL BE CONDUCTING ALL MEETINGS AT THE JACOB HAMBLIN REUNION ON BEHALF OF THE JACOB HAMBLIN LEGACY ORGANIZATION. Date Start Time End Time Event Name Location Event Description 250 E 400 S Family members are encouraged to attend the St. George temple Friday, June 07, 2019 N/A N/A St. George Temple (Open) St. George, UT 84770 before check-in if they arrive early enough and are willing and able. Red Cliffs Stake Center 1285 North Bluff Street Friday, June 07, 2019 6:00 PM 6:20 PM Check-in St. George, UT 84770 Get your name badges here Bid on your favorite items. Donate an item or two to the Auction! We need donations for the silent auction. All proceeds go towards the Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization to help achieve the organization's Red Cliffs Stake Center mission, such as building the Jacob Hamblin Memorial. (Please email 1285 North Bluff Street Sonya Watkins, [email protected], or call 480-229-8082 if you Friday, June 07, 2019 6:30 PM 7:30 PM Silent Auction St. George, UT 84770 would like to donate something to the silent auction.) Red Cliffs Stake Center Dinner is included in your registration fee. Be sure you have paid and 1285 North Bluff Street registered properly according to our records at check-in. (If you have Friday, June 07, 2019 7:00 PM 8:30 PM Dinner St. George, UT 84770 dietary needs, please email [email protected]) Chevonne Pease is a 3rd great grand daughter of Jacob Hamblin.