A Nuyorican Son

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent Latin Artist La India Sola Album Download Torrent

latin artist la india sola album download torrent Latin artist la india sola album download torrent. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 66ca8e0e4e9c0d3e • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. India. There at least two artist by the name of India, one from the United States and one from the United Kingdom. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. While known for her Salsa recordings, India started out recording Freestyle w/ her debut album Breaking Night in 1990 as well as lending her vocals to many house classics. 1) A highly-emotive approach to Latin music has led to Puerto Rico-born and Bronx, New York-raised La India (born: Linda Viera Caballero) being dubbed, "The Princess of Salsa." Her 1994 album, Dicen Que Soy, spent months on the Latin charts. -

La Salsa (Musical)

¿En qué piensan cuando leen la palabra - Salsa? ¿Piensan en lo que comemos con patatas fritas o tortillas? ¿O piensan en la mùsica y el baile? ¿Qué es la Salsa? Salsa es un estilo de música latinoamericana que surgió en Nueva York como resultado del choque de la música afrocaribeña traída por puertoriqueños, cubanos, colombianos, venezolanos, panameños y dominicanos, con el Jazz y el Rock de los norteamericanos. Desde ese entonces, vive deambulando de isla en isla, de país a país, incrementando de tal manera, su riqueza de elementos. Es asi que la Salsa no es una moda pasajera, sinó una corriente musical establecida, de alto valor artístico y gran significado sociocultural: en ella no existen barreras de clase ni de edad. ¿Quienes son los artistas de la Salsa? Celia Cruz La que se va a volver la Reina de la Salsa nació en 1924. Desde niña, al nacer su talento se atreve a cantar en unas fiestas escolares o de barrio, luego en unos concursos radiofónicos. Notaron su talento y entonces empezó una carrera bajo los consejos aclarados de uno de sus profesores. Asi fue que en el 1950, pudo imponerse como cantante en uno de los grupos más famosos de La Havana : la Sonora Matancera. Con este grupo de leyenda fue con quien recorrió toda América Latina durante quinze años, dejando mientras tanto en Cuba su experienca revolucionaria hasta que se instale en 1960 en los Estados Unidos. Hasta ahora, va a guardar una nostalgia de su país, que a menudo se podrá sentir en sus textos y intrevistas. -

Lecuona Cuban Boys

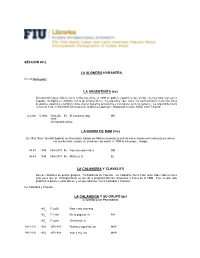

SECCION 03 L LA ALONDRA HABANERA Ver: El Madrugador LA ARGENTINITA (es) Encarnación López Júlvez, nació en Buenos Aires en 1898 de padres españoles, que siendo ella muy niña regresan a España. Su figura se confunde con la de Antonia Mercé, “La argentina”, que como ella nació también en Buenos Aires de padres españoles y también como ella fue bailarina famosísima y coreógrafa, pero no cantante. La Argentinita murió en Nueva York en 9/24/1945.Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, SGAE 2000 T-6 p.66. OJ-280 5/1932 GVA-AE- Es El manisero / prg MS 3888 CD Sonifolk 20062 LA BANDA DE SAM (me) En 1992 “Sam” (Serafín Espinal) de Naucalpan, Estado de México,comienza su carrera con su banda rock comienza su carrera con mucho éxito, aunque un accidente casi mortal en 1999 la interumpe…Google. 48-48 1949 Nick 0011 Me Aquellos ojos verdes NM 46-49 1949 Nick 0011 Me María La O EL LA CALANDRIA Y CLAVELITO Duo de cantantes de puntos guajiros. Ya hablamos de Clavelito. La Calandria, Nena Cruz, debe haber sido un poco más joven que él. Protagonizaron en los ’40 el programa Rincón campesino a traves de la CMQ. Pese a esto, sólo grabaron al parecer, estos discos, y los que aparecen como Calandria y Clavelito. Ver:Calandria y Clavelito LA CALANDRIA Y SU GRUPO (pr) c/ Juanito y Los Parranderos 195_ P 2250 Reto / seis chorreao 195_ P 2268 Me la pagarás / b RH 195_ P 2268 Clemencia / b MV-2125 1953 VRV-857 Rubias y trigueñas / pc MAP MV-2126 1953 VRV-868 Ayer y hoy / pc MAP LA CHAPINA. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Lockett, P.W. (1988). Improvising pianists : aspects of keyboard technique and musical structure in free jazz - 1955-1980. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/8259/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] IMPROVISING PIANISTS: ASPECTS OF KEYBOARD TECHNIQUE AND MUSICAL STRUCTURE IN FREE JAll - 1955-1980. Submitted by Mark Peter Wyatt Lockett as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University Department of Music May 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No I List of Figures 3 IIListofRecordings............,........ S III Acknowledgements .. ..... .. .. 9 IV Abstract .. .......... 10 V Text. Chapter 1 .........e.e......... 12 Chapter 2 tee.. see..... S S S 55 Chapter 3 107 Chapter 4 ..................... 161 Chapter 5 ••SS•SSSS....SS•...SS 212 Chapter 6 SS• SSSs•• S•• SS SS S S 249 Chapter 7 eS.S....SS....S...e. -

Stanley Cowell Samuel Blaser Shunzo Ohno Barney

JUNE 2015—ISSUE 158 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM RAN BLAKE PRIMACY OF THE EAR STANLEY SAMUEL SHUNZO BARNEY COWELL BLASER OHNO WILEN Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 116 Pinehurst Avenue, Ste. J41 JUNE 2015—ISSUE 158 New York, NY 10033 United States New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: [email protected] Interview : Stanley Cowell by anders griffen Andrey Henkin: 6 [email protected] General Inquiries: Artist Feature : Samuel Blaser 7 by ken waxman [email protected] Advertising: On The Cover : Ran Blake 8 by suzanne lorge [email protected] Editorial: [email protected] Encore : Shunzo Ohno 10 by russ musto Calendar: [email protected] Lest We Forget : Barney Wilen 10 by clifford allen VOXNews: [email protected] Letters to the Editor: LAbel Spotlight : Summit 11 by ken dryden [email protected] VOXNEWS 11 by katie bull US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $35 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or money order to the address above In Memoriam 12 by andrey henkin or email [email protected] Festival Report Staff Writers 13 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Fred Bouchard, Stuart Broomer, CD Reviews 14 Katie Bull, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Brad Farberman, Sean Fitzell, Miscellany 41 Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Alex Henderson, Marcia Hillman, Event Calendar Terrell Holmes, Robert Iannapollo, 42 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Robert Milburn, Russ Musto, Sean J. O’Connell, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Ken Waxman There is a nobility to turning 80 and a certain mystery to the attendant noun: octogenarian. -

Playbill 0911.Indd

umass fine arts center CENTER SERIES 2008–2009 1 2 3 4 playbill 1 Latin Fest featuring La India 09/20/08 2 Dave Pietro, Chakra Suite 10/03/08 3 Shakespeare & Company, Hamlet 10/08/08 4 Lura 10/09/08 DtCokeYoga8.5x11.qxp 5/17/07 11:30 AM Page 1 DC-07-M-3214 Yoga Class 8.5” x 11” YOGACLASS ©2007The Coca-Cola Company. Diet Coke and the Dynamic Ribbon are registered trademarks The of Coca-Cola Company. We’ve mastered the fine art of health care. Whether you need a family doctor or a physician specialist, in our region it’s Baystate Medical Practices that takes center stage in providing quality and excellence. From Greenfield to East Longmeadow, from young children to seniors, from coughs and colds to highly sophisticated surgery — we’ve got the talent and experience it takes to be the best. Visit us at www.baystatehealth.com/bmp Supporting The Community We Live In Helps Create a Better World For All Of Us Allen Davis, CFP® and The Davis Group Are Proud Supporters of the Fine Arts Center! The work we do with our clients enables them to share their assets with their families, loved ones, and the causes they support. But we also help clients share their growing knowledge and information about their financial position in useful and appropriate ways in order to empower and motivate those around them. Sharing is not limited to sharing material things; it’s also about sharing one’s personal and family legacy. It’s about passing along what matters most — during life, and after. -

Ran Blake E Sara Serpa

Jazz 11 de maio 2012 Aurora Ran Blake e Sara Serpa Saturday A segunda cena que irá ser pro- É curioso o facto de poucos músicos jetada esta noite é retirada do filme tocarem Saturday, uma bonita balada Spiral Staircase (Silêncio nas Trevas), que a lendária Sarah Vaughan gravou realizado por Robert Siodmak em 1945. no início da sua carreira, para uma Combinando técnicas do expressio- pequena e obscura editora, antes de nismo alemão com o estilo contemporâ- ter sido contratada pela Columbia neo do cinema americano, poderá ver-se ou Mercury, em 1951. Esta canção é a cara de Dorothy McGuire (persona- parecida com Wednesday’s Child ou gem que não consegue falar), na perspe- Thursday’s Child, no sentido em que são tiva do serial killer que acredita que não todas canções melancólicas, com uns há espaço no mundo para a imperfeição. laivos de pensamentos positivos. A última cena projetada será do filme Le Boucher (O Carniceiro) (1970) de Claude When Autumn Sings (R. B. Lynch) Chabrol. Repare-se na beleza dos planos R. B. Lynch é um compositor pouco reco- e no trabalho maravilhoso do diretor nhecido. Esta é uma das quatro canções de fotografia Jean Rabier. A música foi que ele escreveu para Abbey Lincoln. composta por Pierre Jansen e a jovem Abbey gravou todas elas, incluindo Love atriz é Stephane Audran. Lament. Esta peça tem uma melodia extremamente inovadora, com umas Cansaço notas surpreendentes. Abbey Lincoln (Joaquim Campos, Luís Macedo) escreveu a letra para todas estas canções. Cansaço é um poema de Luís de Macedo (1901-1971) cantado por Amália Piano Ran Blake Voz Sara Serpa Dr. -

(46000) Latinas in Popular Performance: from Celia to Selena

THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN DEPARTMENT OF MEXICAN AMERICAN AND LATINA/O STUDIES SPRING 2021 MAS 315 (40640) AND WGS 301 (46000) LATINAS IN POPULAR PERFORMANCE: FROM CELIA TO SELENA MONDAYS AND WEDNESDAYS FROM 10:00 TO 11:30 AM. (SYNCHRONOUS) INTERNET (CANVAS / ZOOM) PROFESSOR: LAURA G. GUTIÉRREZ EMAIL: [email protected] OFFICE PHONE: 471-3543 OFFICE HOURS: ON ZOOM OFFICE HOURS: MONDAYS AND WEDNESDAYS FROM 3:30-4:30 PM & BY APPOINTMENT Land Acknowledgment (I) We would like to acknowledge that we are meeting on Indigenous land. Moreover, (I) We would like to acknowledge and pay our respects to the Carrizo & Comecrudo, Coahuiltecan, Caddo, Tonkawa, Comanche, Lipan Apache, Alabama-Coushatta, Kickapoo, Tigua Pueblo, and all the American Indian and Indigenous Peoples and communities who have been or have become a part of these lands and territories in Texas, here on Turtle Island. Course Description: While this course’s title suggest that the span of the class material covered will begin with a visual cultural analysis of Celia Cruz, the Queen of Salsa, and will end with Selena, the Queen of Tejano, these two figures only conceptually bookend the ideas that will be explored during the semester. This class will begin by sampling a number of performances of Latinas in popular cultural texts to get lay the ground for the analytical and conceptual frameworks that we will be exploring during the semester. First of all, in a workshop format, we will learn to analyze cultural texts that are visual and movement-based. We will, for example, learn to write performance and visual analysis by collectively learning and putting into practice vocabulary connected to the body in movement, space(s), and visual references (from color to specific ethnic tropes). -

Last Stop Ranchara Staged Reading Script (239.48

LAST STOP RANCHERA Script-in-Progress by Latina Theater Lab For a Staged Concert Reading at: The Yerba Buena Center for the Arts February 12, 1999 Dramaturg, Cherríe Moraga. Working version: February 9, 1999 ACT 1 PROLOGUE: (Excerpt from) “Prodigal Hija and The Last Stop Cantina” by Mónica Sánchez Sound cue of heart beating and panting. Lights fade up. PRODIGAL HIJA: I am running And I can't stop Estoy corriendo To the Last Stop Last Stop Ranchera Where all roads lead For those in search of a truth like me MUSICA: Mariachi music to "La Negra". Ends with sound montage of Ranchera endings. This is my quest. This ubiquitous "tan-tan" leaves me no rest. Like a reccurring waking dream, like a ringing echo in my ear, like an audio pebble in my shoe, this musical punctuation hammers at my core, consumes me desde el corazón al patín. I have to get to root of the matter, I have to know: Why? Why, "TAN-TAN"? What is the Genesis of the Finale, "TAN-TAN". Y como el viento que corre, I run: past Banda MUSICA past Cumbia MUSICA past Bolero MUSICA past Corrido MUSICA past Salsa y Son MUSICA until at last, the distant sounds of mariachi and the smell of tequila lead me to my ranchera revelation. In true Ranchera form, I follow my heart, which in this case means to follow my feet, hasta llegar al fondo, straight to the caballo's mouth, to the end of the line, to the last stop ranchera. “Opera en la Misión” by Marlène Ramírez-Cancio MUSICA: Yma Sumac MARLENE: Then the music came in. -

Creative Music Studio Norman Granz Glen Hall Khan Jamal David Lopato Bob Mintzer CD Reviews International Jazz News Jazz Stories Remembering Bert Wilson

THE INDEPENDENT JOURNAL OF CREATIVE IMPROVISED MUSIC Creative Music Studio Norman Granz Glen Hall Khan Jamal David Lopato Bob Mintzer CD Reviews International jazz news jazz stories Remembering bert wilson Volume 39 Number 3 July Aug Sept 2013 romhog records presents random access a retrospective BARRY ROMBERG’S RANDOM ACCESS parts 1 & 2 “FULL CIRCLE” coming soon www.barryromberg.com www.itunes “Leslie Lewis is all a good jazz singer should be. Her beautiful tone and classy phrasing evoke the sound of the classic jazz singers like Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah aughan.V Leslie Lewis’ vocals are complimented perfectly by her husband, Gerard Hagen ...” JAZZ TIMES MAGAZINE “...the background she brings contains some solid Jazz credentials; among the people she has worked with are the Cleveland Jazz Orchestra, members of the Ellington Orchestra, John Bunch, Britt Woodman, Joe Wilder, Norris Turney, Harry Allen, and Patrice Rushen. Lewis comes across as a mature artist.” CADENCE MAGAZINE “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” is the latest recording by jazz vocalist Leslie Lewis and her husband pianist Gerard Hagen. While they were in New York to perform at the Lehman College Jazz Festival the opportunity to record presented itself. “Leslie Lewis & Gerard Hagen in New York” featuring their vocal/piano duo is the result those sessions. www.surfcovejazz.com Release date August 10, 2013. Surf Cove Jazz Productions ___ IC 1001 Doodlin’ - Archie Shepp ___ IC 1070 City Dreams - David Pritchard ___ IC 1002 European Rhythm Machine - ___ IC 1071 Tommy Flanagan/Harold Arlen Phil Woods ___ IC 1072 Roland Hanna - Alec Wilder Songs ___ IC 1004 Billie Remembered - S. -

MESA REDONDA La India Catalina ¿Un Símbolo Apto De Cartagena? ______

303 ____________________________________________________________________ MESA REDONDA La India Catalina ¿Un símbolo apto de Cartagena? ____________________________________________________________________ PARTICIPANTES Gerardo Ardila Elizabeth Cunin Rafael Ortiz Moderador: Alberto Abello Vives Alberto Abello Vives: Una niña nacida en Zamba, hoy Galera Zamba, fue raptada por Diego de Nicuesa en su incursión a la Costa del hoy Caribe Colombiano entre 1509 y 1511. Los españoles la bautizaron con el nombre de Catalina y la llevaron esclavizada a Santo Domingo. Allí fue criada por religiosas que le enseñaron la lengua castellana y la religión católica. Se convirtió en traductora y fue enviada a Gaira, provincia de Santa Marta. De allí fue recogida por Pedro de Heredia, quien la trajo a Cartagena en 1533. Fue con Pedro de Heredia a Zamba y allí se volvió a encontrar con su gente. Dijeron los españoles que en ese entonces Catalina vestía a la usanza española, de zapatillas y abanico. Fue la guía de Heredia y su traductora. Terminó acusándolo en su primer juicio de residencia. Casi 500 años después Catalina está viva en Ursúa, la novela de William Ospina publicada en el 2005. Hay en ese libro unas líneas dedicadas al retorno de esta muchacha legendaria a Galerazamba. El novelista la llama Catalina de Galera Zamba. En el año 2006, Hernán Urbina publica Las huellas de la india Catalina, un ensayo de 140 páginas en el que reconstruye la ruta de sus viajes desde que fuera secuestrada por Diego de Nicuesa, hasta cuando desapareció en las sombras de la historia. El autor se preocupa por su personalidad y sus sentimientos. Se pregunta si 304 ¿Logró Catalina ser feliz? Aporta también a la memoria los recuerdos de quienes hoy son responsables de una Catalina hecha estatua, de pie, empinada, incansable en aquella glorieta cartagenera que hizo famosa. -

Tu Amor Es Mi Fortuna

ASI SON LOS HOMBRES (AGUA BELLA) TU AMOR ES MI FORTUNA (AGUA MARINA) YOU OUTHTA KNOW (ALANIS MORRISETTE) NI TU NI NADIE (ALASKA DINARAMA) QUE ME QUITAN LO BAILAO (ALBITA) ETERNAMENTE BELLA (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) MIRALO MIRALO (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) REINA DE CORAZONES (ALEJANDRA GUZMAN) BESITO DE COCO/CARAMELO (ALQUIMIA) BERENICE (AMPARO SANDINO) CAMINOS DEL CORAZON (AMPARO SANDINO) GOZATE LA VIDA (AMPARO SANDINO) VALERIE (AMY WHITEHOUSE) BANDIDO (ANA BARBARA) LO QUE SON LAS COSAS (ANAIS) TANTO LA QUERIA (ANDY & LUCAS) PAYASO (ANDY MONTAÑEZ) SE FUE Y ME DEJO (ANDY MONTAÑEZ) ANAISAOCO (ANGEL CANALES) BOMBA CARAMBOMBA (ANGEL CANALES) LEJOS DE TI (ANGEL CANALES) SANDRA (ANGEL CANALES) SOLO SE QUE TIENE NOMBRE DE MUJER (ANGEL CANALES) QUE BOMBOM (ANTHONY CRUZ) GAROTA DE IPANEMA (ANTONIO CARLOS JOBIM) CERVECERO (ARMONIA 10) EL SOL NO REGRESARA (ARMONIA 10) HASTA LAS 6 AM (ARMONIA 10) LA CARTA FINAL (ARMONIA 10) LA RICOTONA (ARMONIA 10) SURENA (ARTURO SANDOVAL) LA CURITA (AVENTURA) BESELA YA (BACILOS) PASOS DE GIGANTE (BACILOS) LA TREMENDA (BAMBOLEO) YA NO ME HACES FALTA (BAMBOLEO) YO NO ME PAREZCO A NADIE (BAMBOLEO) EL PILLO (BAMBOLEO) IF NOT NOW THEN WHEN (BASIA) LAGRIMAS NEGRAS (BEBO VALDES) EL AGUA (BOBBY VALENTIN) TE VOY A REGALAR MI AMOR (BONGA) RABIA (BRENDA STAR) DANCING IN THE DARK (BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN) DOS GARDENIAS(BOLERO) (BUENA VISTA S. CLUB) LA CHOLA CADERONA (BUSH Y LOS MAGNIFICOS) MI BOMBOM (CABAS) DE QUE ME SIRVE QUERERTE (CALLE CIEGA) UNA VEZ MAS (CALLE CIEGA) COMO SI NADA (CAMILO AZUQUITA) COLGANDO EN TUS MANOS (CARLOS BAUTE) LA MARAVILLA (CARLOS VIVES) TORO MATA (CELIA CRUZ) BEMBA COLORA (CELIA CRUZ) KIMBARA (CELIA CRUZ) LA VIDA ES UN CARNAVAL (CELIA CRUZ) NO ME HABLES DE AMOR(BOLERO) (CELIA CRUZ) UD ABUSO (CELIA CRUZ) VIEJA LUNA(BOLERO) (CELIA CRUZ) YO SI SOY VENENO (CELIA CRUZ) SALVAJE (CESAR FLORES) PROCURA (CHICHI PERALTA) ESTOY AQUÍ (CHIKY SALSA) MAMBO INFLUENCIADO (CHUCHO VALDES) EL VIENTO ME DA (COMBO DEL AYER) ME ENAMORO DE TI (COMBO LOCO) GOZA LA VIDA (CONJ.