The Emerging Metamodern Sensibility in Narrative: a Case Study of Things Left Forgotten and the Dai Gyakuten Saiban Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1

The Primitivist Critique of Modernity: Carl Einstein and Walter Benjamin1 David Pan In the “Sirens” episode in Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus, relying on nothing more than the wax in his sailors’ ears and the rope binding him to the mast of his ship, was able to hear the sirens’ song without being drawn to his death like all the sailors before him.2 Franz Kafka, finally giving the sirens their due, points out that their song could certainly pierce wax and would lead a man to burst all bonds. Instead of attributing Odysseus’ sur- vival to his cunning use of technical means, which he calls “childish mea- sures,”3 Kafka attributes it to the sirens’ use of an even more horrible weapon than their song: their silence. Believing his trick had worked, Odysseus did not hear their silence, but imagined he heard the sound of their singing, for no one could resist “the feeling of having triumphed over them by one’s own strength, and the consequent exaltation that bears down everything before it.”4 The sirens disappeared from Odysseus’per- ceptions, which were focused entirely on himself. Kafka concludes: “If the sirens had possessed consciousness, they would have been annihilated at that moment. But they remained as they had been; all that had hap- pened was that Odysseus had escaped them.”5 Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno have argued that this ancient 1. From Primitive Renaissance: Rethinking German Expressionism by David Pan. Copyright 2001 by the University of Nebraska Press. 2. Homer, Odyssey, Book 12, pp.166-200. 3. -

Performance Is a Genre in Which Art Is Presented "Live," Usually by the Artist but Sometimes with Collaborators Or Performers

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Performance is a genre in which art is presented "live," usually by the artist but sometimes with collaborators or performers. It has had a role in avant-garde art throughout the 20th century, playing an important part in anarchic movements such as Futurism and Dada. Indeed, whenever artists have become discontented with conventional forms of art, such as painting and traditional modes of sculpture, they have often turned to performance as a means to rejuvenate their work. The most significant flourishing of Performance art took place following the decline of modernism and Abstract Expressionism in the 1960s, and it found exponents across the world. Performance art of this period was particularly focused on the body, and is often referred to as Body Art. This reflects the period's so- called 'dematerialization of the art object,' and the flight from traditional media. It also reflects the political ferment of the time: the rise of feminism, which encouraged thought about the division between the personal and political; and anti-war activism, which supplied models for politicized art 'actions.' Although the concerns of performance artists have changed since the 1960s, the genre has remained a constant presence, and has largely been welcomed into the conventional museums and galleries from which it was once excluded. Key Points The foremost purpose of Performance art has almost always been to challenge the conventions of traditional forms of visual art such as painting and sculpture. When these modes no longer seem to answer artists' needs - when they seem too conservative, or to enmeshed in the traditional art world and too distant from ordinary people - artists have often turned to Performance in order to find new audiences and test new ideas. -

New Modernism(S)

New Modernism(s) BEN DUVALL 5 Intro: Surfaces and Signs 13 The Typography of Utopia/Dystopia 27 The Hyperlinked Sign 41 The Aesthetics of Refusal 5 Intro: Surfaces and Signs What can be said about graphic design, about the man- ner in which its artifact exists? We know that graphic design is a manipulation of certain elements in order to communicate, specifically typography and image, but in order to be brought together, these elements must exist on the same plane–the surface. If, as semi- oticians have said, typography and images are signs in and of themselves, then the surface is the locus for the application of sign systems. Based on this, we arrive at a simple equation: surface + sign = a work of graphic design. As students and practitioners of this kind of “surface curation,” the way these elements are functioning currently should be of great interest to us. Can we say that they are operating in fundamentally different ways from the way they did under modern- ism? Even differently than under postmodernism? Per- haps the way the surface and sign are treated is what distinguishes these cultural epochs from one another. We are confronted with what Roland Barthes de- fined as a Text, a site of interacting and open signs, 6 NEW MODERNISM(S) and therefore, a site of reader interpretation and of SIGNIFIER + SIGNIFIED = SIGN semiotic play.1 This is of utmost importance, the treat- ment of the signs within a Text is how we interpret, Physical form of an Ideas represented Unit of meaning idea, e.g. -

Connections Between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M

Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal Volume 36 Article 2 January 2009 "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M. Brandon Hillsdale College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/ctamj Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, and the Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies Commons Recommended Citation Brandon, J. (2009). "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky's Hypermodern Times and Post- Soviet Russian Cinema. Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal, 36, 7-22. This General Interest is brought to you for free and open access by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication and Theater Association of Minnesota Journal by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Brandon: "Brother," Enjoy Your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles CTAMJ Summer 2009 7 “Brother,” Enjoy your Hypermodernity! Connections between Gilles Lipovetsky’s Hypermodern Times and Post-Soviet Russian Cinema James M. Brandon Associate Professor [email protected] Department of Theatre and Speech Hillsdale College Hillsdale, MI ABSTRACT In prominent French social philosopher Gilles Lipovetsky’s Hypermodern Times (2005), the author asserts that the world has entered the period of hypermodernity, a time where the primary concepts of modernity are taken to their extreme conclusions. The conditions Lipovetsky described were already manifesting in a number of post-Soviet Russian films. In the tradition of Slavoj Zizek’s Enjoy Your Symptom (1992), this essay utilizes a number of post-Soviet Russian films to explicate Lipovetsky’s philosophy, while also using Lipovetsky’s ideas to explicate the films. -

Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon

INTERLITT ERA RIA 2019, 24/2: 495–508 495 Bleeding Edge of Postmodernism Bleeding Edge of Postmoder nism: Metamodern Writing in the Novel by Thomas Pynchon SIMON RADCHENKO Abstract. Many different models of co ntemporary novel’s description arose from the search for methods and approaches of post-postmodern texts analysis. One of them is the concept of metamodernism, proposed by Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker and based on the culture and philosophy changes at the turn of this century. This article argues that the ideas of metamodernism and its main trends can be successfully used for the study of contemporary literature. The basic trends of metamodernism were determined and observed through the prism of literature studies. They were implemented in the analysis of Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Bleeding Edge (2013). Despite Pynchon being usually considered as postmodern writer, the use of metamodern categories for describing his narrative strategies confirms the idea of the novel’s post-postmodern orientation. The article makes an endeavor to use metamodern categories as a tool for post-postmodern text studies, in order to analyze and interpret Bleeding Edge through those categories. Keywords: meta-modernism; postmodernism; Thomas Pynchon; oscillation; new sincerity How can we study something that has not been completely described yet? Although discussions of a paradigm shift have been around long enough, when talking about contemporary literary phenomena we are still using the categories of feeling rather than specific instruments. Perception of contemporary lit era- ture as post-postmodern seems dated today. However, Joseph Tabbi has questioned the novelty of post-postmodernism as something new, different from postmodernism and proposes to consider the abolition of irony and post- modernism (Tabbi 2017). -

122520182414.Pdf

Archive of SID University of Tabriz-Iran Journal of Philosophical Investigations ISSN (print): 2251-7960/ (online): 2423-4419 Vol. 12/ No. 24/ fall 2018 Postmodernism, Philosophy and Literature* Hossein Sabouri** Associate Professor, University of Tabriz, Iran Abstract No special definite definition does exist for postmodernism however it has had an inordinate effect on art, architecture, music, film, literature, philosophy, sociology, communications, fashion, and technology. The main body of this work can be seen as an admiration and reverence for the values and ideals associated with postmodern philosophy as well as postmodern literature. , I have argued that postmodern has mainly influenced philosophy and literature and they are recognized and praised for their multiplicity. Postmodernism might seem exclusive in its work, its emphasis on multiplicity and the decentered subject makes very uncomfortable reading for traditional theorists or philosophers. It rejects western values and beliefs as only small part of the human experience and it rejects such ideas, beliefs, culture and norms of the western. Integrity is fragmented apart into unharmonious narratives which lead to a shattering of identity and an overall breakdown of any idea of the self. Relativism and Self- reflexivity have replaced self-confidence due to the postmodern belief that all representation distorts reality. I have also referred that in a sense; postmodernism is a part of modernism we find the instantaneous coexistence of these two methods of expression and thinking, especially in visual arts and literature. Key words: Postmodernism, modernism, Philosophy, Literature, self, relativism, * Received date: 2018/07/15 Accepted date: 2018/09/26 ** E-mail: [email protected] www.SID.ir Archive of SID272/ Philosophical Investigations, Vol. -

Metamodernism, Or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism

“We’re Lost Without Connection”: Metamodernism, or Exploring the Afterlife of Postmodernism MA Thesis Faculty of Humanities Media Studies MA Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Giada Camerra S2103540 Media Studies: Comparative Literature and Literary Theory Leiden, 14-06-2020 Supervisor: Dr. M.J.A. Kasten Second reader: Dr.Y. Horsman Master thesis submitted in accordance with the regulations of Leiden University 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1: Discussing postmodernism ........................................................................................ 10 1.1 Postmodernism: theories, receptions and the crisis of representation ......................................... 10 1.2 Postmodernism: introduction to the crisis of representation ....................................................... 12 1.3 Postmodern aesthetics ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3.1 Sociocultural and economical premise ................................................................................. 14 1.3.2 Time, space and meaning ..................................................................................................... 15 1.3.3 Pastiche, parody and nostalgia ............................................................................................ -

Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in . Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Bäckström, P. (2008) One Earth, Four or Five Words: The Notion of ”Avant-Garde” Problematized Action Yes, 1(7): 1-17 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:lnu:diva-89603 ACTION YES http://www.actionyes.org/issue7/backstrom/backstrom-printfriendl... s One Earth, Four or Five Words The Notion of 'Avant-Garde' Problematized by Per Bäckström L’art, expression de la Société, exprime, dans son essor le plus élevé, les tendances sociales les plus avancées; il est précurseur et révélateur. Or, pour savoir si l’art remplit dignement son rôle d’initiateur, si l’artiste est bien à l’avant-garde, il est nécessaire de savoir où va l’Humanité, quelle est la destinée de l’Espèce. [---] à côté de l’hymne au bonheur, le chant douloureux et désespéré. […] Étalez d’un pinceau brutal toutes les laideurs, toutes les tortures qui sont au fond de notre société. [1] Gabriel-Désiré Laverdant, 1845 Metaphors grow old, turn into dead metaphors, and finally become clichés. This succession seems to be inevitable – but on the other hand, poets have the power to return old clichés into words with a precise meaning. Accordingly, academic writers, too, need to carry out a similar operation with notions that are worn out by frequent use in everyday language. -

Metamodernism and Vaporwave: a Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 3 Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Nicholas Morrissey University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Recommended Citation Morrissey, Nicholas. “Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture.” Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology 14, no. 1 (2021): 64-82. https://doi.org/10.5206/notabene.v14i1.13361. Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Abstract With the advent of Web 2.0, new forms of cultural and aesthetic texts, including memes and user generated content (UGC), have become increasingly popular worldwide as streaming and social media services have become more ubiquitous. In order to acknowledge the relevance and importance of these texts in academia and art, this paper conducts a three-part analysis of Vaporwave—a unique multimedia style that originated within Web 2.0—through the lens of a new cultural philosophy known as metamodernism. Relying upon a breadth of cultural theory and first-hand observations, this paper questions the extent to which Vaporwave is interested in metamodernist constructs and asks whether or not the genre can be classed as a metamodernist text, noting the dichotomy and extrapolation of nostalgia promoted by the genre and the unique instrumentality it offers to its consumers both visually and sonically. This paper ultimately theorizes that online culture will continue to play an important role in cultural production, aesthetic mediation, and even -

Transmodern Reconfigurations of Territoriality

societies Article Transmodern Reconfigurations of Territoriality, Defense, and Cultural Awareness in Ken MacLeod’s Cosmonaut Keep Jessica Aliaga-Lavrijsen Centro Universitario de la Defensa Zaragoza, Zaragoza 50090, Spain; [email protected] Received: 5 September 2018; Accepted: 17 October 2018; Published: 19 October 2018 Abstract: This paper focuses on the science fiction (SF) novel Cosmonaut Keep (2000)—first in the trilogy Engines of Light, which also includes Dark Light (2001) and Engines of Light (2002)—by the Scottish writer Ken MacLeod, and analyzes from a transmodern perspective some future warfare aspects related to forthcoming technological development, possible reconfigurations of territoriality in an expanding cluster of civilizations travelling and trading across distant solar systems, expanded cultural awareness, and space ecoconsciousness. It is my argument that MacLeod’s novel brings Transmodernism, which is characterized by a “planetary vision” in which human beings sense that we are interdependent, vulnerable, and responsible, into the future. Hereby, MacLeod’s work expands the original conceptualization of the term “Transmodernism” as defined by Rodríguez Magda, and explores possible future outcomes, showing a unique awareness of the fact that technological processes are always linked to political and power-related uses. Keywords: cultural awareness; future warfare; globalization; Fifth-Generation War; intergalactic territoriality; planetary civilizations; SF; space ecoconsciousness; speculative fiction; technological development; transmodernism “Where there is no vision, the people perish.” —Proverbs 29:18 “If these are the early days of a better nation there must be hope, and a hope of peace is as good as any, and far better than a hollow hoarding greed or the dry lies of an aweless god.” —Graydon Saunders 1. -

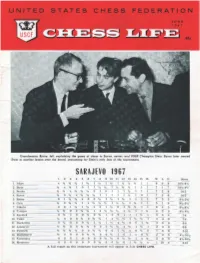

Sarajevo 1967 ° "' 1 '"

Grondmaster ayme, lefl, explafntnq the qallle 01 d»eu to 80"011, c.nter, and USSR Champion Stein, Byrne later floated SteIn 10 anOfher leuon o"er the board. accountmq tor Sleln's only lou 01 lhe lournamenl, SARAJEVO 1967 I 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 W L D !: ~~::: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.... .::: :' .' ...: . ~ ~~, ---.-~;.-.::~;--:~;-"~,==~: =~~f. =~"tl =j~~=;~t="ii"'\'----;.~:;:--;"-;-·I - ::- -;:===-;~'----;~'---";:""~=- 10 ~ .4- ~ 3. tknko , If.! Y.i: % 0 I 0 1 1 I ~ I \ _ ;-1 _~'~ ,;--;;-, - \1)-5 x 1h 'h ':-l - '--'' 1 I I 1 'h I 0 I ,';-,,'c-- -:';-_-- 1().5_ °1 '""' 1h x 0 0 n 1 n I ¥, I 1 1 I ,..' .....;:3_ ~ 9Ik.5 ~ h 1 x I,i h ~ 1 n h I I,i 1;.--:1_ _ 5 1 9 9h . ~~ ° "1 h 1 I,i x 0 I 'h 0 1 "':"''-''''7----:-1 t 6" 5'- - 8'7 .6% o o lit liz 1 x 1,1: .., .., 1 "':t I t ¥l -.' , 2 ~ 81.1 f1lh 1 0 0 n 0 If. :< 0 0 1 J I n _ -;-I _ ';--;-6_ ,_ _ ,.. - 11 Duc1n tcin .. .. .... ... n ~ ~ ~ ~ : ~ "~'- : : ~ ~ ~ --,~,,-:~:-~ ----.-~ :: ~! 12. Ja.noS('vic .... ... ... ... .. ~_-;";... _~ ~ _Ifl "1 ;;:0'--;,;..0 _ 0,,-:"':-"''7--;;:''--''''' 1 ~"''-.;.I _ _.;:-' _ ;!i 8 f.. 9 13. Pict%.Sch ................................... \o!t Vr 'tit;. _ ";. ,-~O:- 0 n 'fl 0 0 . __1 'h x 0 1:'.1 0 1 6 --;8- - - 5- 10 14. Bogdanuvic .. .................. Y.t 0 0 0 0 lit Yt 0 0 Yt 1 0 I x 0 h 2 8 5 _ _ " "1.100" :~ : ~:~;:~.