Class, Religion and Society in Limerick City, 1922-1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bishop Brendan Leahy

th . World Day of Poor 19 November, 2017 No great economic success story possible as long as homelessness and other poverty crises deepen – Bishop Brendan Leahy Ireland cannot claim itself an economic success while it allows the neglect of its poor, Bishop of Limerick Brendan Leahy has stated in his letter to the people of the diocese to mark the first World Day of the Poor. The letter - read at Masses across the diocese for the official World Day of the Poor called by Pope Francis – says that with homelessness at an unprecedented state of crisis today in Ireland, it is almost unjust and unchristian to claim economic success. “Throughout the centuries we have great examples of outreach to the poor. The most outstanding example is that of Francis of Assisi, followed by many other holy men and women over the centuries. In Ireland we can think of great women such as Catherine McAuley and Nano Nagle. “Today the call to hear the cry of the poor reaches us. In our Diocese we are blessed to have the Limerick Social Services Council that responds in many ways. There are many other initiatives that reach out to the homeless, refugees, people in situations of marginalisation,” he wrote. “But none of us can leave it to be outsourced to others to do. Each of us has to do our part. Today many of us live a privileged life in the material sense compared to generations gone by, Today is Mission Sunday and the Holy Father invites all Catholics to contribute to a special needing pretty much nothing. -

Roinn Cosanta

ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 624 Witness Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Identity. Member of A.O.H. and of Cumann na mBan. Subject. Reminiscences of the period 1895-1924. Conditions, if any, Stipulated by Witness. Nil File No. S.1901 Form B.S.M.2 Statement by Mrs. Mary Flannery Woods, 17 Butterfield Crescent, Rathfarnham, Dublin. Memories of the Land League and Evictions. I am 76 years of age. I was born in Monasteraden in County Sligo about five miles from Ballaghaderreen. My first recollections are Of the Lend League. As a little girl I used to go to the meetings of Tim Healy, John Dillon and William O'Brien, and stand at the outside of the crowds listening to the speakers. The substance of the speeches was "Pay no Rent". It people paid rent, organizations such as the "Molly Maguire's" and the "Moonlighters" used to punish them by 'carding them', that means undressing them and drawing a thorny bush over their bodies. I also remember a man, who had a bit of his ear cut off for paying his rent. He came to our house. idea was to terrorise them. Those were timid people who were afraid of being turned out of their holdings if they did not pay. I witnessed some evictions. As I came home from school I saw a family sitting in the rain round a small fire on the side of the road after being turned out their house and the door was locked behind them. -

De Courcy O'dwyer

DE COURCY O’DWYER FOR SALE BY PRIVATE TREATY ‘SPRINGFIELD’ STATION ROAD KILLONAN CO. LIMERICK V94HKP3 PRICE REGION: €625,000 PHONE: 061 410 410 PSRA No. 002371 www.propertypartners.ie EMAIL: [email protected] DESCRIPTION Springfield is a truly superb family home tucked away in this tranquil setting in the ever popular location of Killonan. This exceptional private residence of c.3250 sq.ft. on approx 1 Acre has been restored and extended to a high standard throughout with beautiful period type features, offering gracious proportions and an abundance of light and space throughout. The ground floor comprises of a well appointed entrance hall with staircase leading to the upper level. Off the hallway is a large bright dining room with 3 roof lights making this an ideal place to entertain. On the opposite side of the hallway is a well proportioned living room with a door leading to the kitchen/breakfast room area. The kitchen has extensive wall and floor units throughout while the breakfast room benefits from a large open fireplace with free standing solid fuel stove and double doors leading to the walled courtyard. Beyond the kitchen is an office area with guest W.C. and a good sized utility room with plenty of storage space. To the back of the kitchen/breakfast room is a spacious sitting room with a door to the rear garden and a second stairwell leading to the first floor level. This completes the ground floor accommodation. On the split level first floor there are five double bedrooms, two with ensuite bathrooms. -

Mungretgate Brochure Web.Pdf

Get the most out of family life at Mungret Gate, a new development of beautiful spacious homes nestled between Raheen and Dooradoyle, 5km from Limerick City Centre. Set in a well-established and well-serviced area, the homes at Mungret Gate benefit from countryside surroundings with plenty of activites nearby including a playground, stunning scenery and 2km of walk and cycle paths. Ideal for families of all ages, Mungret Gate is surrounded by an abundance of established and highly regarded local amenities. Several schools are in the immediate area, including Mungret Community College, Limerick City East Educate Together, and St Nessans National School, along with a crèche and Montessori school. Leisure time will be well spent at one of the many sports clubs in the area. Mungret has its own football and GAA clubs, offering fun for all the family, while the famous Garryowen rugby club is just down the road. Mungret Gate itself offers walking and cycling in its surrounding parkland, along with a playground that includes a sensory area and facilities for all ages. 1.Education limerick city& Schools east educate together 2. tiny friends creche and monterssori 3. st. nessan’s n.s. 4. st gabriels school 5. limerick education centre 6. crescent college comprehensive 15 12 7. catherine mcauley school What’s Nearby 8. st. paul’s n.s. r iver 9. laurel hill sh n18 10. griffith college an n Shannon irport 11. limerick college of further education o 7 n Galway 11 12. mungret community college 13 13. gaelscoil an raithin 16 14. mary immaculate college 10 15. -

Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018

Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 MOUNTMELLICK LOCAL AREA PLAN 2012-2018 Contents VOLUME 1 - WRITTEN STATEMENT Page Laois County Council October 2012 1 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 2 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Contents Page Introduction 5 Adoption of Mountmellick Local area Plan 2012-2018 7 Chapter 1 Strategic Context 13 Chapter 2 Development Strategy 20 Chapter 3 Population Targets, Core Strategy, Housing Land Requirements 22 Chapter 4 Enterprise and Employment 27 Chapter 5 Housing and Social Infrastructure 40 Chapter 6 Transport, Parking and Flood Risk 53 Chapter 7 Physical Infrastructure 63 Chapter 8 Environmental Management 71 Chapter 9 Built Heritage 76 Chapter 10 Natural Heritage 85 Chapter 11 Urban Design and Development Management Standards 93 Chapter 12 Land-Use Zoning 115 3 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 4 Mountmellick Local Area Plan 2012-2018 Introduction Context Mountmellick is an important services and dormitory town located in north County Laois, 23 kms. south-east of Tullamore and 11 kms. north-west of Portlaoise. It lies at the intersection of regional routes R422 and R433 with the National Secondary Route N80. The River Owenass, a tributary of the River Barrow, flows through the town in a south- north trajectory. Population-wise Mountmellick is the third largest town in County Laois, after Portlaoise and Portarlington. According to Census 2006, the recorded population of the town is 4, 069, an increase of 21% [708] on the recorded population of Census 2002 [3,361]. The population growth that occurred in Mountmellick during inter-censal period 2002-2006 has continued through to 2011 though precise figures for 2011 are still pending at time of writing. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Manor Brook, Adare, Co. Limerick

MANOR BROOK ADARE, CO. LIMERICK Loving life in Adare MANOR BROOK ADARE, CO. LIMERICK 2 ⧸ 3 Come home to village life at its best The charm and beauty of living in one of Ireland’s most idyllic historic villages, Adare, Co Limerick is as picturesque as it is lively. The exclusivity of being within walking distance from every attraction you could want - such as premium boutiques and exclusive restaurants, to excellent schools, newly- built playground, the Manor Fields, not to mention the world-renowned Adare Manor Hotel & Golf Resort. Adare is situated just 15km from all that Limerick City has to offer. This is life at Manor Brook - an exciting new development from Bloom Capital Ltd. Here, the style and elegance of your own beautiful, contemporary-designed home meets the established peace and family magic of traditional village living. All set in a region that is ranked as one of the top 10 locations in Western Europe in which to invest. Come home to belonging, to community and to convenience. Come home to Manor Brook. MANOR BROOK ADARE, CO. LIMERICK 4 ⧸ 5 Manor Brook at a glance 40 TWO-STOREY HOMES BOTH DETACHED & SEMI-DETACHED SITUATED IN ONE OF IRELAND’S MOST IDYLLIC HISTORIC VILLAGES 4 DIFFERENT DESIGNS WITH SIZES RANGING FROM NEXT TO THE FIVE-STAR LUXURY RESORT, ADARE MANOR HOTEL 1,157 SQ FT TO 2,078 SQ FT AND GOLF RESORT MODERN, SPACIOUS, ELEGANT & CONTEMPORARY MANY AWARD-WINNING RESTAURANTS, CAFÉS AND PUBS CLOSE TO FOUR EXCELLENT PRIMARY SCHOOLS AS WELL ALL MAJOR ROUTES AND MOTORWAYS ARE EASILY ACCESSIBLE AS PLAYING FIELDS AND PLAYGROUNDS FROM MANOR BROOK MANOR BROOK ADARE, CO. -

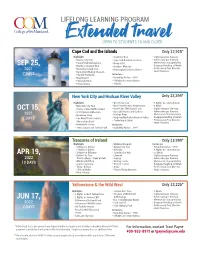

Extended Travel OPEN to STUDENTS 18 and OLDER

LIFELONG LEARNING PROGRAM Extended travel OPEN TO STUDENTS 18 AND OLDER Cape Cod and the Islands Only $2,925* Highlights • Cranberry Bog • Sightseeing per Itinerary • Boston City Tour • Cape Cod National Seashore • Admissions per Itinerary • Faneuil Hall Marketplace • Newport RI • Motorcoach Transportation SEP 25, • Martha’s Vineyard Tour • Breakers Mansion • Baggage Handling at Hotels • Professional Tour Director 2021 • Nantucket Island Visit • New England Lobster Dinner • Nantucket Whaling Museum • Hotel Transfers 7 DAYS • Plimoth Plantation Inclusions • Mayflower II • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU • Plymouth Rock • 6 Nights Accommodations • Provincetown • 9 Meals .................................................................................................................................................... New York City and Hudson River Valley Only $3,399* Highlights • West Point Tour • 6 Nights Accommodations • New York City Tour • New Paltz/Historic Huguenot St. • 8 Meals OCT 15, • Statue of Liberty/Ellis Island • Hyde Park-FDR Historic Site • Sightseeing per Itinerary • 9/11 Memorial/Museum • Boscobel House and Gardens • Admissions per Itinerary 2021 • Broadway Show • Hudson River • Motorcoach Transportation • One World Trade Center/ • Kingston/Manhattan/Hudson Valley • Baggage Handling at Hotels 7 DAYS • Professional Tour Director Observation Deck • Crown Maple Syrup • Hotel Transfers • Rockefeller Center Inclusions • Times Square and Central Park • Roundtrip Airfare – HOU ................................................................................................................................................... -

Midlands-Our-Past-Our-Pleasure.Pdf

Guide The MidlandsIreland.ie brand promotes awareness of the Midland Region across four pillars of Living, Learning, Tourism and Enterprise. MidlandsIreland.ie Gateway to Tourism has produced this digital guide to the Midland Region, as part of suite of initiatives in line with the adopted Brand Management Strategy 2011- 2016. The guide has been produced in collaboration with public and private service providers based in the region. MidlandsIreland.ie would like to acknowledge and thank those that helped with research, experiences and images. The guide contains 11 sections which cover, Angling, Festivals, Golf, Walking, Creative Community, Our Past – Our Pleasure, Active Midlands, Towns and Villages, Driving Tours, Eating Out and Accommodation. The guide showcases the wonderful natural assets of the Midlands, celebrates our culture and heritage and invites you to discover our beautiful region. All sections are available for download on the MidlandsIreland.ie Content: Images and text have been provided courtesy of Áras an Mhuilinn, Athlone Art & Heritage Limited, Athlone, Institute of Technology, Ballyfin Demense, Belvedere House, Gardens & Park, Bord na Mona, CORE, Failte Ireland, Lakelands & Inland Waterways, Laois Local Authorities, Laois Sports Partnership, Laois Tourism, Longford Local Authorities, Longford Tourism, Mullingar Arts Centre, Offaly Local Authorities, Westmeath Local Authorities, Inland Fisheries Ireland, Kilbeggan Distillery, Kilbeggan Racecourse, Office of Public Works, Swan Creations, The Gardens at Ballintubbert, The Heritage at Killenard, Waterways Ireland and the Wineport Lodge. Individual contributions include the work of James Fraher, Kevin Byrne, Andy Mason, Kevin Monaghan, John McCauley and Tommy Reynolds. Disclaimer: While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in the information supplied no responsibility can be accepted for any error, omission or misinterpretation of this information. -

Proposed Record of Protected Structures Newcastle West Municipal District

DRAFT LIMERICK DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2022-2028 Volume 3B Proposed Record of Protected Structures Newcastle West Municipal District June 2021 Contents 1.0 Introduction Record of Protected Structures (RPS) – Newcastle West Municipal District 1 2.0 Record of Protected Structures - Newcastle West Municipal District ................................. 2 1 1.0 Introduction Record of Protected Structures (RPS) – Newcastle West Municipal District Limerick City & County Council is obliged to compile and maintain a Record of Protected Structures (RPS) under the provisions of the Planning and Development Act 2000 (as amended). A Protected Structure, unless otherwise stated, includes the interior of the structure, the land lying within the curtilage of the structure, and other structures lying within that curtilage and their interiors. The protection also extends to boundary treatments. The proposed RPS contained within Draft Limerick Development Plan 2022 - 2028 Plan represents a varied cross section of the built heritage of Limerick. The RPS is a dynamic record, subject to revision and addition. Sometimes, ambiguities in the address and name of the buildings can make it unclear whether a structure is included on the RPS. Where there is uncertainty you should contact the Conservation Officer. The Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht is responsible for carrying out surveys of the architectural heritage on a county-by-county basis. Following the publication of the NIAH for Limerick City and County, and any subsequent Ministerial recommendations, the Council will consider further amendments to the Record of Protected Structures. The NIAH survey may be consulted online at buildingsofireland.ie There are 286 structures listed as Protected Structures in the Newcastle West Metropolitan District. -

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil Na Héireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland

Aguisíní Appendices Aguisín 1: Comóradh Céad Bliain Ollscoil na hÉireann Appendix 1: Centenary of the National University of Ireland Píosa reachtaíochta stairiúil ab ea Acht Ollscoileanna na hÉireann, 1908, a chuir deireadh go foirmeálta le tréimhse shuaite in oideachas tríú leibhéal na hEireann agus a d’oscail caibidil nua agus nuálaíoch: a bhunaigh dhá ollscoil ar leith – ceann amháin díobh i mBéal Feirste, in ionad sean-Choláiste na Ríona den Ollscoil Ríoga, agus an ceann eile lárnaithe i mBaile Átha Cliath, ollscoil fheidearálach ina raibh coláistí na hOllscoile Ríoga de Bhaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh, athchumtha mar Chomh-Choláistí d’Ollscoil nua na hÉirean,. Sa bhliain 2008, rinne OÉ ceiliúradh ar chéad bliain ar an saol. Is iomaí athrú suntasach a a tharla thar na mblianta, go háiriithe nuair a ritheadh Acht na nOllscoileanna i 1997, a rinneadh na Comh-Choláistí i mBaile Átha Cliath, Corcaigh agus Gaillimh a athbhunú mar Chomh-Ollscoileanna, agus a rinneadh an Coláiste Aitheanta (Coláiste Phádraig, Má Nuad) a athstruchtúrú mar Ollscoil na hÉireann, Má Nuad – Comh-Ollscoil nua. Cuireadh tús le comóradh an chéid ar an 3 Nollaig 2007 agus chríochnaigh an ceiliúradh le mórchomhdháil agus bronnadh céime speisialta ar an 3 Nollaig 2008. Comóradh céad bliain ón gcéad chruinniú de Sheanad OÉ ar an lá céanna a nochtaíodh protráid den Seansailéirm, an Dr. Garret FitzGerald. Tá liosta de na hócáidí ar fad thíos. The Irish Universities Act 1908 was a historic piece of legislation, formally closing a turbulent chapter in Irish third level education and opening a new and innovational chapter: establishing two separate universities, one in Belfast, replacing the old Queen’s College of the Royal University, the other with its seat in Dublin, a federal university comprising the Royal University colleges of Dublin, Cork and Galway, re-structured as Constituent Colleges of the new National University of Ireland. -

Transatlantic: the Flying Boats of Foynes

Transatlantic: The Flying Boats of Foynes A Documentary by Michael Hanley Transatlantic: The Flying Boats of Foynes Introduction: She'd come down into the water the very same as a razor blade... barely touch it ‐ you'd hardly see the impression it would make. That was usual, but other times they might hit it very hard... ah yes, they were great days, there's no doubt about it. Poem: I'm sure you still remember the famous flying boats, B.O.A.C., P.A.A. and American Export. With crews - some were small, some tall, some dressed in blue, And in a shade of silvery grey, Export hostess and crew. Narrator: The town of Foynes is situated 15 miles west of Limerick city at the mouth of the River Shannon. Today it is a quietly prosperous port that at first glimpse belies its significance in the history of aviation. 60 years ago the flying boats, the first large commercial aeroplanes ploughed their heavy paths through the rough weather of the transatlantic run to set their passengers down here, on the doorstep of Europe, gateway to a new world. In a time of economic depression and growing international conflict, Foynes welcomed the world in the embrace of the Shannon estuary. "It can't be done!" That was most people's reaction to the idea of flying the Atlantic. After the First War, aircraft could just not perform to the levels needed to traverse the most treacherous ocean in the world. But the glory and the economic rewards for those who succeeded were huge.