Jazzin' the Classics: the AACM's Challenge to Mainstream Aesthetics Author(S): Ronald M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Underserved Communities

National Endowment for the Arts FY 2016 Spring Grant Announcement Artistic Discipline/Field Listings Project details are accurate as of April 26, 2016. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Click the grant area or artistic field below to jump to that area of the document. 1. Art Works grants Arts Education Dance Design Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts 2. State & Regional Partnership Agreements 3. Research: Art Works 4. Our Town 5. Other Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Information is current as of April 26, 2016. Arts Education Number of Grants: 115 Total Dollar Amount: $3,585,000 826 Boston, Inc. (aka 826 Boston) $10,000 Roxbury, MA To support Young Authors Book Program, an in-school literary arts program. High school students from underserved communities will receive one-on-one instruction from trained writers who will help them write, edit, and polish their work, which will be published in a professionally designed book and provided free to students. Visiting authors, illustrators, and graphic designers will support the student writers and book design and 826 Boston staff will collaborate with teachers to develop a standards-based curriculum that meets students' needs. Abada-Capoeira San Francisco $10,000 San Francisco, CA To support a capoeira residency and performance program for students in San Francisco area schools. Students will learn capoeira, a traditional Afro-Brazilian art form that combines ritual, self-defense, acrobatics, and music in a rhythmic dialogue of the body, mind, and spirit. -

The Academy of Vocal Arts

April 7, 2005 Contact: Matthew Levy 215-893-0140 [email protected] Philadelphia Music Project 2005 Grant Recipients Academy of Vocal Arts, $60,000 to support concert versions of Le Portrait de Manon and La Navarraise, two important but rarely performed verismo operas by Jules Massanet. Vocalists will include James Valenti (tenor), Ailyn Perez (soprano), Jennifer G. Hsuing (mezzo-soprano), and Keith Miller (baritone). Performances will take place at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in January 2006. Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, $160,000 over two years to engage the American Composers Orchestra (ACO) in a residency that will bring ACO’s acclaimed Orchestra Underground programs to the Annenberg Center for a series of six new music concerts. Guest artists and organizations participating in the project include Todd Reynolds (violin), Ryuichi Sakamoto (laptop), Bill T. Jones, So Percussion, Pilobolus, and the Ridge Theater. The residency will include educational and outreach activities, as well as a program of works by Philadelphia- area composers. Choral Arts Society of Philadelphia, $30,000 to host Maestro Dale Warland, the former music director and founder of the Dale Warland Singers, as guest conductor for a program of works by Howard Hanson, Rudi Tas, Arvo Pärt, Benjamin Britten, James MacMillan, Frank Ferko, Alexandre Gretchaninoff, Vytautus Miškinis, and Henryk Górecki. A regional choral conducting workshop is also planned with Mr. Warland and CASP’s Artistic Director, Matthew Glandorf. Doylestown School of Music and the Arts, $12,140 in support of Stretched Strings, a series of four concerts exploring acoustic guitar practice within a variety of styles, including Travis Picking, Classical, Fingerstyle, and Blues. -

Joseph Jarman's Black Case Volume I & II: Return

Joseph Jarman’s Black Case Volume I & II: Return From Exile February 13, 2020 By Cam Scott When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi- generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day. Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified. -

Vindicating Karma: Jazz and the Black Arts Movement

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-2007 Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/ W. S. Tkweme University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Tkweme, W. S., "Vindicating karma: jazz and the Black Arts movement/" (2007). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 924. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/924 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Massachusetts Amherst Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/vindicatingkarmaOOtkwe This is an authorized facsimile, made from the microfilm master copy of the original dissertation or master thesis published by UMI. The bibliographic information for this thesis is contained in UMTs Dissertation Abstracts database, the only central source for accessing almost every doctoral dissertation accepted in North America since 1861. Dissertation UMI Services From:Pro£vuest COMPANY 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106-1346 USA 800.521.0600 734.761.4700 web www.il.proquest.com Printed in 2007 by digital xerographic process on acid-free paper V INDICATING KARMA: JAZZ AND THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT A Dissertation Presented by W.S. TKWEME Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 W.E.B. -

Museum Archivist

Newsletter of the Museum Archives Section Museum Archivist Summer 2020 Volume 30, Issue 2 Letter From the Chair Fellow MAS and SAA members, To be blunt, we are currently in the midst of a challenging period of historic proportions. On top of a charged atmosphere filled with vitriol, 2020 has witnessed the unfolding of both a global pandemic and racial tensions exacerbated by systemic racism in law enforcement. The combination of this perfect storm has sowed a climate of chaos and uncertainty. It is easy to feel demoralized and discouraged. For your own mental health, allow yourself to feel. Allow yourself to take a breath and acknowledge that you are bearing witness to a uniquely challenging period like few in global history. Yet, there is reason to hope. The trite phrase, “that which does not kill us only makes us stronger” has significance. We adapt, learn, grow and improve. If this all is to be viewed as an incredible challenge, rest assured, we will overcome it. (To use yet another timeless phrase, “this, too, shall pass.”) I am curious to see what new measures, what new policies, what new courses of action we, as professionals in the field(s) of libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) will implement to further enhance and reinforce the primary goals of our respective professions. One question that keeps coming to mind is how the archives field—specifically as it relates to museums— will survive and adapt in the post-COVID-19 world. People will continue to turn to publicly available research material to learn and educate others. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

May • June 2013 Jazz Issue 348

may • june 2013 jazz Issue 348 &blues report now in our 39th year May • June 2013 • Issue 348 Lineup Announced for the 56th Annual Editor & Founder Bill Wahl Monterey Jazz Festival, September 20-22 Headliners Include Diana Krall, Wayne Shorter, Bobby McFerrin, Bob James Layout & Design Bill Wahl & David Sanborn, George Benson, Dave Holland’s PRISM, Orquesta Buena Operations Jim Martin Vista Social Club, Joe Lovano & Dave Douglas: Sound Prints; Clayton- Hamilton Jazz Orchestra, Gregory Porter, and Many More Pilar Martin Contributors Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, Dewey Monterey, CA - Monterey Jazz Forward, Nancy Ann Lee, Peanuts, Festival has announced the star- Wanda Simpson, Mark Smith, Duane studded line up for its 56th annual Verh, Emily Wahl and Ron Wein- Monterey Jazz Festival to be held stock. September 20–22 at the Monterey Fairgrounds. Arena and Grounds Check out our constantly updated Package Tickets go on sale on to the website. Now you can search for general public on May 21. Single Day CD Reviews by artists, titles, record tickets will go on sale July 8. labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 2013’s GRAMMY Award-winning years of reviews are up and we’ll be lineup includes Arena headliners going all the way back to 1974. Diana Krall; Wayne Shorter Quartet; Bobby McFerrin; Bob James & Da- Comments...billwahl@ jazz-blues.com vid Sanborn featuring Steve Gadd Web www.jazz-blues.com & James Genus; Dave Holland’s Copyright © 2013 Jazz & Blues Report PRISM featuring Kevin Eubanks, Craig Taborn & Eric Harland; Joe No portion of this publication may be re- Lovano & Dave Douglas Quintet: Wayne Shorter produced without written permission from Sound Prints; George Benson; The the publisher. -

Why Jazz Still Matters Jazz Still Matters Why Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Journal of the American Academy

Dædalus Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Spring 2019 Why Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2019 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, guest editors with Farah Jasmine Griffin Gabriel Solis · Christopher J. Wells Kelsey A. K. Klotz · Judith Tick Krin Gabbard · Carol A. Muller Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Why Jazz Still Matters” Volume 148, Number 2; Spring 2019 Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson, Guest Editors Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Pianist Geri Allen. Photograph by Arne Reimer, provided by Ora Harris. © by Ross Clayton Productions. Contents 5 Why Jazz Still Matters Gerald Early & Ingrid Monson 13 Following Geri’s Lead Farah Jasmine Griffin 23 Soul, Afrofuturism & the Timeliness of Contemporary Jazz Fusions Gabriel Solis 36 “You Can’t Dance to It”: Jazz Music and Its Choreographies of Listening Christopher J. Wells 52 Dave Brubeck’s Southern Strategy Kelsey A. K. Klotz 67 Keith Jarrett, Miscegenation & the Rise of the European Sensibility in Jazz in the 1970s Gerald Early 83 Ella Fitzgerald & “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” Berlin 1968: Paying Homage to & Signifying on Soul Music Judith Tick 92 La La Land Is a Hit, but Is It Good for Jazz? Krin Gabbard 104 Yusef Lateef’s Autophysiopsychic Quest Ingrid Monson 115 Why Jazz? South Africa 2019 Carol A. -

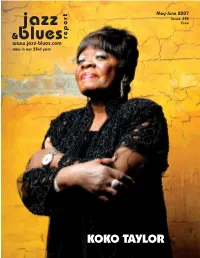

May-June 293-WEB

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Musica Jazz Autore Titolo Ubicazione

MUSICA JAZZ AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE AA.VV. Blues for Dummies MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. \The \\metronomes MSJ/CD MET AA.VV. Beat & Be Bop MSJ/CD BEA AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Casino lights '99 MSJ/CD CAS AA.VV. Victor Jazz History vol. 13 MSJ/CD VIC AA.VV. Blue'60s MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. 8 Bold Souls MSJ/CD EIG AA.VV. Original Mambo Kings (The) MSJ/CD MAM AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 1 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. New Orleans MSJ/CD NEW AA.VV. Woodstock Jazz Festival 2 MSJ/CD WOO AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. \Le \\grandi trombe del Jazz MSJ/CD GRA AA.VV. Real birth of Fusion two (The) MSJ/CD REA AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe III: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI AA.VV. Celebrating the music of Weather Report MSJ/CD CEL AA.VV. Night and Day : The Cole Porter Songbook MSJ/CD NIG AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. \L'\\album jazz più bello del mondo MSJ/CD ALB AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Blues jam in Chicago MSJ/CD BLU AA.VV. Saint-Germain-des-Pres Cafe II: the finest electro-jazz compilationMSJ/CD SAI Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball Adderley MSJ/CD ADD Aires Tango Origenes [CD] MSJ/CD AIR Al Caiola Serenade In Blue MSJ/CD ALC Allison, Mose Jazz Profile MSJ/CD ALL Allison, Mose Greatest Hits MSJ/CD ALL Allyson, Karrin Footprints MSJ/CD ALL Anikulapo Kuti, Fela Teacher dont't teach me nonsense MSJ/CD ANI Armstrong, Louis Louis In New York MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Louis Armstrong live in Europe MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis Satchmo MSJ/CD ARM Armstrong, Louis -

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk Tenorsaxofonist, Født 20.10.1934 I Chicago, IL, D

Eddie Who? - Eddie Harris Amerikansk tenorsaxofonist, født 20.10.1934 i Chicago, IL, d. 5.11.1996 Sanger og pianist som barn i baptistkirker og spillede senere vibrafon og tenorsax. Debuterede som pianist med Gene Ammons før universitetsstudier i musik. Spillede med bl.a. Cedar Walton i 7. Army Symphony Orchestra. Fik i 1961 et stort hit og jazzens første guldplade med filmmelodien "Exodus", hvad der i de følgende år gav ham visse problemer med accept i jazzmiljøet. Udsendte 1965 The in Sound med bl.a. hans egen komposition Freedom Jazz Dance, som siden er indgået i jazzens standardrepertoire. Spillede fra 1966 elektrificeret saxofon og hybrider af sax og basun. Flirtede med rock på Eddie Harris In the UK (Atlantic 1969). Spillede 1969 på Montreux festivalen med Les McCann (Swiss Movement, Atlantic) og skrev 1969-71 musik til Bill Cosbys tv-shows. Spillede i 80'erne med bl.a. Tete Montoliu og Bo Stief (Steps Up, SteepleChase, 1981) og igen med Les McCann. Som sideman med bl.a. Jimmy Smith, Horace Silver, Horace Parlan og John Scofield (Hand Jive, Blue Note, 1993). Optrådte trods sygdom, så sent som maj 1996. Indspillede et stort antal plader for mange selskaber, fra 80'erne mest europæiske. Med udgangspunkt i bopmusikken udviklede Harris sine eksperimenter til en meget personlig stil med umiddelbart genkendelig, egenartet vokaliserende tone, fra 70'erne krydret med (ofte lange), humoristisk filosofisk/satiriske enetaler. Følte sig ofte underkendt som musiker og satiriserede over det i sin "Eddie Who". Kilde: Politikens Jazz Leksikon, 2003, red. Peter H. Larsen og Thorbjørn Sjøgren There's a guys (Chorus) You ought to know Eddie Harris .. -

May 2001 03 Jazz Ed

ALL ABOUT JAZZ monthly edition — may 2001 03 Jazz Ed. 04 Pat Metheny: New Approaches 09 The Genius Guide to Jazz: Prelude EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Aaron Wrixon 14 The Fantasy Catalog: Tres Joses ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael Martino 18 Larry Carlton and Steve Lukather: Guitar Giants CONTRIBUTORS: 28 The Blue Note Catalog: All Blue Glenn Astarita, Mathew Bahl, Jeff Fitzgerald, Chris Hovan, Allen Huotari, Nils Jacobson, Todd S. Jenkins, Joel Roberts, Chris M. Slawecki, Derek Taylor, Don Williamson, 32 Joel Dorn: Jazz Classics Aaron Wrixon. ON THE COVER: Pat Metheny 42 Dena DeRose: No Detour Ahead PUBLISHER: 48 CD Reviews Michael Ricci Contents © 2001 All About Jazz, Wrixon Media Ventures, and contributors. Letters to the editor and manuscripts welcome. Visit www.allaboutjazz.com for contact information. Unsolicited mailed manuscripts will not be returned. Welcome to the May issue of All About Jazz, Pogo Pogo, or Joe Bat’s Arm, Newfoundland Monthly Edition! (my grandfather is rolling over in his grave at This month, we’re proud to announce a new the indignity I have just committed against columnist, Jeff Fitzgerald, and his new, er, him) — or WHEREVER you’ve been hiding column: The Genius Guide to Jazz. under a rock all this while — and check some Jeff, it seems, is blessed by genius and — of Metheny’s records out of the library. as is the case with many graced by voluminous The man is a guitar god, and it’s an intellect — he’s not afraid to share that fact honour and a privilege to have Allen Huotari’s with us.