View PDF: Otrump Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia

Physical Geography of Southeast Asia Creating an Annotated Sketch Map of Southeast Asia By Michelle Crane Teacher Consultant for the Texas Alliance for Geographic Education Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 Guiding Question (5 min.) . What processes are responsible for the creation and distribution of the landforms and climates found in Southeast Asia? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 2 Draw a sketch map (10 min.) . This should be a general sketch . do not try to make your map exactly match the book. Just draw the outline of the region . do not add any features at this time. Use a regular pencil first, so you can erase. Once you are done, trace over it with a black colored pencil. Leave a 1” border around your page. Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 3 Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 4 Looking at your outline map, what two landforms do you see that seem to dominate this region? Predict how these two landforms would affect the people who live in this region? Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 5 Peninsulas & Islands . Mainland SE Asia consists of . Insular SE Asia consists of two large peninsulas thousands of islands . Malay Peninsula . Label these islands in black: . Indochina Peninsula . Sumatra . Label these peninsulas in . Java brown . Sulawesi (Celebes) . Borneo (Kalimantan) . Luzon Texas Alliance for Geographic Education; http://www.geo.txstate.edu/tage/ September 2013 6 Draw a line on your map to indicate the division between insular and mainland SE Asia. -

Spatial Variability of Levees As Measured Using the CPT

2nd International Symposium on Cone Penetration Testing, Huntington Beach, CA, USA, May 2010 Spatial Variability of Levees as Measured Using the CPT R.E.S. Moss Assistant Professor, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo J. C. Hollenback Graduate Researcher, U.C. Berkeley J. Ng Undergraduate Researcher, Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo ABSTRACT: The spatial variability of a soil deposit is something that is commonly discussed but difficult to quantify. The heterogeneity as a function of lateral distance can be critical to the design of long engineered structures such as highways, bridges, levees, and other lifelines. This paper presents a methodology for using CPT mea- surements to quantifying the spatial variability of cone tip resistance along a levee in the California Bay Delta. The results, presented in the form of a general relative va- riogram, identify the distance at which the maximum spatial variability is achieved for a given soil strata. This information helps define minimally correlated stretches of levee for proper failure and risk analysis. Presented herein are methods of interpret- ing, calculating, and analyzing CPT data to arrive at the quantified spatial variability with respect to different static and seismic failure modes common to levee systems. 1 INTRODUCTION Spatial variability of engineering properties in soil strata is inherent to the nature of soil. Spatial variability is controlled primarily by the depositional environment where high energy systems usually deposit materials with high spatial variability (e.g. al- luvial gravels) and low energy systems usually deposit materials with low spatial va- riability (e.g. lacustrine clays). This spatial variability is generally taken into account in geotechnical design in a qualitative empirical manner through appropriately spaced borings to assess the changing subsurface conditions. -

LIESSE Où Klaxonner Pour Faire Chier P. 17 LA POSTE Schwaller De Rien P. 16 DÉCROISSANCE Un Art Consommé P. 7 FOOT Bilan Et P

Vendredi 22 juin 2018 // No 369 // 9e année CHF 4.– // Abonnement annuel CHF 160.– // www.vigousse.ch FOOT DÉCROISSANCE LA POSTE LIESSE Bilan et perspectives Un art consommé Schwaller Où klaxonner pour PP. 2, 3, 4, 14 P. 7 de rien P. 16 faire chier P. 17 JAA – 1001 Lausanne P.P./Journal – Poste CH SA – Poste Lausanne P.P./Journal JAA – 1001 2 C’EST PAS POUR DIRE ! POINT V 3 opposants se font mystérieusement empoisonner, un Etat qui inonde le Y a faute, ou bien ? reste du monde de fake news, de faits Parité bien alternatifs, de théories du complot et FOOT NEWS On nous cache tout, on nous dit rien ! La vérité est de désinformation stupide, une clique malmenée de partout, sauf, heureusement, dans le seul domaine qui truque toutes les élections depuis qui compte : le football. des années, bref, le royaume du faux ordonnée… et de la magouille. Mais pour le foot, faut pas déconner quand même : on Séverine André Ce lundi, tandis que les petits Suisses mais y a hors-jeu là ! » ; « Hé ! Quel peut parfaitement faire confiance à se remettaient à peine de la nuit de connard, il l’a poussé ! » ; ou « Quel ces mythos. Car le football, c’est la t soudain, dimanche 17 juin, après des folie faisant suite au glorieux match enculé, il s’est laissé tomber ! » Très vérité. nul contre le Brésil, les élèves fran- clairement, c’est le cas que p si, et siècles d’iniquité, la Suisse s’enthousiasme çais gambergeaient sec devant leur seulement si, il y a effectivement Autre preuve que la vérité, c’est pour l’égalité. -

Groundwater Issues in the Paleozoic Plateau a Taste of Karst, a Modicum of Geology, and a Whole Lot of Scenery

GGroundwaterroundwater IssuesIssues inin tthehe PaleozoicPaleozoic PlateauPlateau A Taste of Karst, a Modicum of Geology, and a Whole Lot of Scenery Iowa Groundwater Association Field Trip Guidebook No. 1 Iowa Geological and Water Survey Guidebook Series No. 27 Dunning Spring, near Decorah in Winneshiek County, Iowa September 29, 2008 In Conjunction with the 53rd Annual Midwest Ground Water Conference Grand River Center, Dubuque, Iowa, September 30 – October 2, 2008 Groundwater Issues in the Paleozoic Plateau A Taste of Karst, a Modicum of Geology, and a Whole Lot of Scenery Iowa Groundwater Association Field Trip Guidebook No. 1 Iowa Geological and Water Survey Guidebook Series No. 27 In Conjunction with the 53rd Annual Midwest Ground Water Conference Grand River Center, Dubuque, Iowa, September 30 – October 2, 2008 With contributions by M.K. Anderson Robert McKay Iowa DNR-Water Supply Engineering Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Bruce Blair Jeff Myrom Iowa DNR-Forestry Iowa DNR-Solid Waste Michael Bounk Eric O’Brien Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Karen Osterkamp Lora Friest Iowa DNR-Fisheries Northeast Iowa Resource Conservation and Development Jean C. Prior Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey James Hedges Luther College James Ranum Natural Resources Conservation Service John Hogeman Winneshiek County Landfi ll Operator Robert Rowden Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Claire Hruby Iowa DNR-Geographic Information Systems Joe Sanfi lippo Iowa DNR-Manchester Field Offi ce Bill Kalishek Gary Siegwarth Iowa DNR-Fisheries Iowa DNR-Fisheries George E. Knudson Mary Skopec Luther College Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Bob Libra Stephanie Surine Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Huaibao Liu Paul VanDorpe Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Iowa DNR-Geological and Water Survey Iowa Department of Natural Resources Richard Leopold, Director September 2008 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . -

Hogback Is Ridge Formed by Near- Vertical, Resistant Sedimentary Rock

Chapter 16 Landscape Evolution: Geomorphology Topography is a Balance Between Erosion and Tectonic Uplift 1 Topography is a Balance Between Erosion and Tectonic Uplift 2 Relief • The relief in an area is the maximum difference between the highest and lowest elevation. – We have about 7000 feet of relief between Boulder and the Continental divide. Relief 3 Mountains and Valleys • A mountain is a large mass of rock that projects above surrounding terrain. • A mountain range is a continuous area of high elevation and high relief. • A valley is an area of low relief typically formed by and drained by a single stream. • A basin is a large low-lying area of low relief. In arid areas basins commonly have closed topography (no river outlet to the sea). Mountains • Typically occur in ranges. • Glaciated forms –Horn –Arête • Desert Mountains – Vertical Cliffs – Alluvial Fans 4 Mountain Landforms: Horn Deserts: Vertical Cliffs and Alluvial Fans 5 Valleys and Basins • River Valleys – U-shape (Glacial) – V-shape (Active Water erosion) – Flat-floored (depositional flood plain) • Tectonic (Fault) Valleys (Basins) – Tectonic origin – San Luis Valley – Jackson Hole – Great Basin U-shaped Valley: Glacial Erosion 6 V-shaped Valley: Active water erosion Flat-floored Valley: Depositional Flood Plain 7 Desert and Semi-arid Landforms • A plateau is a broad area of uplift with relatively little internal relief. • A mesa is a small (<10 km2)plateau bounded by cliffs, commonly in an area of flat-lying sedimentary rocks. • A butte is a small (<1000m2) hill bounded by cliffs Plateau, Mesa, Butte 8 Colorado National Monument Canyonlands 9 Desert and Semi-arid Landforms • A cuesta is an asymmetric ridge in dipping sedimentary rocks as the Flatirons. -

2019 Pleasure-Way Brochure 1

FROM THE CEO My name is Dean Rumpel and I am CEO of Pleasure-Way At Pleasure-Way, we recognize the extraordinary Industries Ltd. I have been involved with Pleasure-Way people who build our motorhomes. It is the incredible from the very beginning and I am proud to say I have efforts of our employees that have made Pleasure- worked my way up through the ranks over the years. Way unsurpassed in the industry. Their dedication and My family has been invested in the RV industry since commitment to quality is evident in every detail of our 1968 when my father, Merv Rumpel, opened his own coaches and in our incomparable customer service. RV dealership. In 1986, he decided that he could build a better, higher-quality camper van than what he was We strive to build the perfect coach for our owners seeing in the market and Pleasure-Way was born. Merv’s so they can rest easy knowing they made the right vision of a luxury product with innovative features and purchasing decision. Whether you are a current or superior quality led to the company’s humble beginnings. potential owner, you know we have a vested interest in your satisfaction, and providing you with the best The cornerstone of Pleasure-Way is my father’s old- ownership experience possible. fashioned work ethic, pride in craftsmanship and a “customer comes first” approach to business. We remain committed to follow these principles today. I am proud to say that Pleasure-Way is still a family-owned Dean Rumpel and operated company with three generations involved CEO, Pleasure-Way Industries Ltd. -

Springfield Plateau Regional Restoration Plan And

Springfield Plateau Regional Restoration Plan and Environmental Assessment U.S Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Missouri Department of Natural Resources On the cover. Diamond Grove Prairie Conservation Area, Diamond, MO. The Springfield Plateau of southwest Missouri was once mostly prairie with oak-hickory hardwood forests in areas of greater relief such as along streams. Hardwood forests are more frequent on the eastern side of the plateau with a shift to prairie to the west. Photo courtesy of Wayne Rhodus, Rhodus Photography, Bonner Springs, KS. ii TRUSTEES: U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Missouri Department of Natural Resources RESPONSIBLE FEDERAL AGENCY: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3, CONTACT: John Weber Environmental Contaminants Specialist U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 101 Park DeVille Dr. Suite A Columbia, MO 65203 573-234-2132 x177 Email: [email protected] RESPONSIBLE STATE AGENCY: Missouri Department of Natural Resources CONTACT: Tim Rielly Assessment and Restoration Manager Missouri Department of Natural Resources, P.O. Box 176 Jefferson City, MO 65102-0176 573-526-3353 Email: [email protected] DATE: May 2012 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 General Information 1 1.2 Scope and Scale of the Springfield Plateau Regional Restoration Plan 2 1.3 The Springfield Plateau Regional Restoration Plan and the Request for Proposal Process 6 1.4 Authority and Legal Requirements 6 1.5 Summary of Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration -

Geology of the Northern Portion of the Fish Lake Plateau, Utah

GEOLOGY OF THE NORTHERN PORTION OF THE FISH LAKE PLATEAU, UTAH DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State - University By DONALD PAUL MCGOOKEY, B.S., M.A* The Ohio State University 1958 Approved by Edmund M." Spieker Adviser Department of Geology CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. ................................ 1 Locations and accessibility ........ 2 Physical features ......... _ ................... 5 Previous w o r k ......... 10 Field work and the geologic map ........ 12 Acknowledgements.................... 13 STRATIGRAPHY........................................ 15 General features................................ 15 Jurassic system......................... 16 Arapien shale .............................. 16 Twist Gulch formation...................... 13 Morrison (?) formation...................... 19 Cretaceous system .............................. 20 General character and distribution.......... 20 Indianola group ............................ 21 Mancos shale. ................... 24 Star Point sandstone................ 25 Blackhawk formation ........................ 26 Definition, lithology, and extent .... 26 Stratigraphic relations . ............ 23 Age . .............................. 23 Price River formation...................... 31 Definition, lithology, and extent .... 31 Stratigraphic relations ................ 34 A g e .................................... 37 Cretaceous and Tertiary systems . ............ 37 North Horn formation. .......... -

Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain

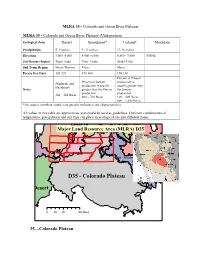

MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus MLRA 35 - Colorado and Green River Plateaus (Utah portion) Ecological Zone Desert Semidesert* Upland* Mountain Precipitation 5 -9 inches 9 -13 inches 13-16 inches Elevation 3,000 -5,000 4,500 -6,500 5,800 - 7,000 NONE Soil Moisture Regime Typic Ardic Ustic Aridic Aridic Ustic Soil Temp Regime Mesic/Thermic Mesic Mesic Freeze free Days 120-220 120-160 100-130 Percent of Pinyon Percent of Juniper production is Shadscale and production is usually usually greater than blackbrush Notes greater than the Pinyon the Juniper production production 300 – 500 lbs/ac 400 – 700 lbs/ac 100 – 500 lbs/ac 800 – 1,000 lbs/ac *the aspect (north or south) can greatly influence site characteristics. All values in this table are approximate and should be used as guidelines. Different combinations of temperature, precipitation and soil type can place an ecological site into different zones. Rocky Mountains Major Land ResourceBasins and Plateaus Area (MLRA) D35 D36 - Southwestern Plateaus, Mesas, and Foothills D35 - Colorado Plateau Desert 07014035 Miles 35—Colorado Plateau This area is in Arizona (56 percent), Utah (22 percent), New Mexico (21 percent), and Colorado (1 percent). It makes up about 71,735 square miles (185,885 square kilometers). The cities of Kingman and Winslow, Arizona, Gallup and Grants, New Mexico, and Kanab and Moab, Utah, are in this area. Interstate 40 connects some of these cities, and Interstate 17 terminates in Flagstaff, Arizona, just outside this MLRA. The Grand Canyon and Petrified Forest National Parks and the Canyon de Chelly and Wupatki National Monuments are in the part of this MLRA in Arizona. -

Landforms of the United States Are Indeed Keys to an Understanding of the Earth

of the UNITED STATES U.S.DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The United States contains a great variety of land forms which offer dramatic contrasts to a cross country traveler. Mountains and desert areas, tropical jungles and areas of permanently frozen subsoil, deep canyons and broad plains are examples of theN ation's varied surface. The present-day landforms- the features that make up the face of the earth-are products of the slow, sculpturing actions of streams and geologic processes that have been at work throughout the ages since the earth's beginning. Landforms may be classified as depositional or erosional. Depositional landforms have the character and shape of the deposits of which they are made. They include beaches, stream terraces, and alluvial fans at the foot of mountains. Erosional landforms are ones that have been created by agents of erosion such as rivers and streams, rain, and ice. The most widespread erosional landforms are those made by running water acting over very long periods of time. Rain, accumulating as a sheet of water on the ground, does not travel far before it gathers in channels. These channels, like branches of a tree, extend from a myriad of branchlets to larger and larger branches and finally to main trunk rivers. Stream channels are abundant in a humid climate and commonly one cannot travel in a straight line for more than a quarter of a mile without encountering one. Stream channels also occur in deserts, but they are farther apart and water runs in them only inter mittently. -

The Shatsky Rise Oceanic Plateau Structure from Two-Dimensional Multichannel Seismic Refl Ection Profi Les and Implications for Oceanic Plateau Formation

Downloaded from specialpapers.gsapubs.org on June 2, 2015 The Geological Society of America Special Paper 511 2015 The Shatsky Rise oceanic plateau structure from two-dimensional multichannel seismic refl ection profi les and implications for oceanic plateau formation Jinchang Zhang* William W. Sager† Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843, USA Jun Korenaga Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06520, USA ABSTRACT The Shatsky Rise is one of the largest oceanic plateaus, a class of volcanic fea- tures whose formation is poorly understood. It is also a plateau that was formed near spreading ridges, but the connection between the two features is unclear. The geologic structure of the Shatsky Rise can help us understand its formation. Deeply penetrating two-dimensional (2-D) multichannel seismic (MCS) refl ection profi les were acquired over the southern half of the Shatsky Rise, and these data allow us to image its upper crustal structure with unprecedented detail. Synthetic seismo- grams constructed from core and log data from scientifi c drilling sites crossed by the MCS lines establish the seismic response to the geology. High-amplitude basement refl ections result from the transition between sediment and underlying igneous rock. Intrabasement refl ections are caused by alternations of lava fl ow packages with dif- fering properties and by thick interfl ow sediment layers. MCS profi les show that two of the volcanic massifs within the Shatsky Rise are immense central volcanoes. The Tamu Massif, the largest (~450 km × 650 km) and oldest (ca. 145 Ma) volcano, is a single central volcano with a rounded shape and shallow fl ank slopes (<0.5°–1.5°), characterized by lava fl ows emanating from the volcano center and extending hun- dreds of kilometers down smooth, shallow fl anks to the surrounding seafl oor. -

Cumberland Plateau Geological History

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area Oneida, Tennessee Geology and History of the Cumberland Plateau Geological History Rising over 1000 feet above the region around it, the Cumberland Plateau is a large, flat-topped tableland. Deceptively rugged, the Plateau has often acted as a barrier to man and nature’s attempts to overcome it. The Plateau is characterized by rugged terrain, a moderate climate, and abundant rainfall. Although the soils are typically thin and infertile, the area was once covered by a dense hardwood forest equal to that of the Appalachians less than sixty miles to the east. As a landform, this great plateau reaches from north-central Alabama through Tennessee and Kentucky and Pennsylvania to the western New York border. Geographers call this landform the Appalachian Plateau, although it is known by various names as it passes through the differ ent regions. In Tennessee and Kentucky, it is called the Cumberland Plateau. Within this region, the Cumberland River and its tributaries are formed. A view from any over- look quickly confirms that the area is indeed a plateau. The adjoining ridges are all the same height, presenting a flat horizon. The River Systems The Clear Fork River and the New River come together to form the Big South Fork of the Cumberland River, the third largest tributary to the Cumberland. The Big South Fork watershed drains an area of 1382 square Leatherwood Ford in the evening sun miles primarily in Scott, Fentress, and Morgan counties in Tennessee and Wayne and Overlooks McCreary counties in Kentucky.