Design of the Apostle Islands Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WLSSB Map and Guide

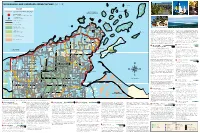

WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY (WLSSB) DEVILS ISLAND NORTH TWIN ISLAND MAP KEY ROCKY ISLAND SOUTH TWIN ISLAND CAT ISLAND WISCONSIN LAKE SUPERIOR SCENIC BYWAY APOSTLE ISLANDS BEAR ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE KIOSK LOCATION IRONWOOD ISLAND SCENIC BYWAY NEAR HERBSTER SAILING ON LAKE SUPERIOR LOST CREEK FALLS KIOSKS CONTAIN DETAILED INFORMATION ABOUT EACH LOCATION SAND ISLAND VISITOR INFORMATION OUTER ISLAND YORK ISLAND SEE REVERSE FOR COMPLETE LIST µ OTTER ISLAND FEDERAL HIGHWAY MANITOU ISLAND RASPBERRY ISLAND STATE HIGHWAY COUNTY HIGHWAY 7 EAGLE ISLAND NATIONAL PARKS ICE CAVES AT MEYERS BEACH BAYFIELD PENINSULA AND THE APOSTLE ISLANDS FROM MT. ASHWABAY & NATIONAL FOREST LANDS well as a Heritage Museum and a Maritime Museum. Pick up Just across the street is the downtown area with a kayak STATE PARKS K OAK ISLAND STOCKTON ISLAND some fresh or smoked fish from a commercial fishery for a outfitter, restaurants, more lodging and a historic general & STATE FOREST LANDS 6 GULL ISLAND taste of Lake Superior or enjoy local flavors at one of the area store that has a little bit of everything - just like in the “old (!13! RED CLIFF restaurants. If you’re brave, try the whitefish livers – they’re a days,” but with a modern flair. Just off the Byway you can MEYERS BEACH COUNTY PARKS INDIAN RESERVATION local specialty! visit two popular waterfalls: Siskiwit Falls and Lost Creek & COUNTY FOREST LANDS Falls. West of Cornucopia you will find the Lost Creek Bog HERMIT ISLAND Walk the Brownstone Trail along an old railroad grade or CORNUCOPIA State Natural Area. Lost Creek Bog forms an estuary at the take the Gil Larson Nature Trail (part of the Big Ravine Trail MICHIGAN ISLAND mouths of three small creeks (Lost Creek 1, 2, and 3) where System) which starts by a historic apple shed, continues RESERVATION LANDS they empty into Lake Superior at Siskiwit Bay. -

Apostle Islands National Lakehore Geologic Resources Inventory

Geologic Resources Inventory Scoping Summary Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Division Prepared by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich National Park Service August 7, 2010 US Department of the Interior The Geologic Resources Inventory (GRI) provides each of 270 identified natural area National Park System units with a geologic scoping meeting and summary (this document), a digital geologic map, and a geologic resources inventory report. The purpose of scoping is to identify geologic mapping coverage and needs, distinctive geologic processes and features, resource management issues, and monitoring and research needs. Geologic scoping meetings generate an evaluation of the adequacy of existing geologic maps for resource management, provide an opportunity to discuss park-specific geologic management issues, and if possible include a site visit with local experts. The National Park Service held a GRI scoping meeting for Apostle Islands National Lakeshore on July 20-21, 2010 both out in the field on a boating site visit from Bayfield, Wisconsin, and at the headquarters building for the Great Lakes Network in Ashland, Wisconsin. Jim Chappell (Colorado State University [CSU]) facilitated the discussion of map coverage and Bruce Heise (NPS-GRD) led the discussion regarding geologic processes and features at the park. Dick Ojakangas from the University of Minnesota at Duluth and Laurel Woodruff from the U.S. Geological Survey presented brief geologic overviews of the park and surrounding area. Participants at the meeting included NPS staff from the park and Geologic Resources Division; geologists from the University of Minnesota at Duluth, Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, and U.S. Geological Survey; and cooperators from Colorado State University (see table 2). -

Breeding and Feeding Ecology of Bald Eagl~S in the Apostle Island National Lakeshore

BREEDING AND FEEDING ECOLOGY OF BALD EAGL~S IN THE APOSTLE ISLAND NATIONAL LAKESHORE by Karin Dana Kozie A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin December 1986 APPROVED BY THE GRADUATE COMMITTEE OF; Dr. Raymond K. Anderson, Major Advisor Professor of Wildlife Dr. Neil F Professor of Dr. Byron Shaw Professor of Water Resorces ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people donated considerable time and effort to this project. I wish to thank Drs. Neil Payne and Byron Shaw -of-n my graduate ncommittee, for---providing Use fliT comments on this manuscript; my committee chairman, Dr. Ray Anderson, whose support, patience and knowledge will long be appreciated. Special thanks to Chuck Sindelar, eagle biologist for the state of Wisconsin, for conducting aerial surveys, organizing banding crews and providing a vast supply of knowledge and time, and to Ron Eckstein and Dave Evans of the banding crew, for their climbing expertise. I greatly appreciate the help of the following National Park Service personnel: Merryll Bailey, ecologist,.provided equipment, logistical arrangements and fisheries expertise; Maggie Ludwig graciously provided her home, assisted with fieldwork and helped coordinate project activities on the mainland while researchers were on the islands; park ranger/naturalists Brent McGinn, Erica Peterson, Neil Howk, Ellen Maurer and Carl and Nancy Loewecke donated their time and knowledge of the islands. Many people volunteered the~r time in fieldwork; including Jeff Rautio, Al Bath, Laura Stanley, John Foote, Sandy Okey, Linda Laack, Jack Massopust, Dave Ross, Joe Papp, Lori Mier, Kim Pemble and June Rado. -

The Archeological Investigation of Four Lighthouse Complexes at the Western End of Lake Superior: the 1988 Testing Program Withi~Postle Islands National Lakeshore

()-/~'7 The Archeological Investigation of Four Lighthouse Complexes at the Western End of lake Superior: The 1988 Testing Program Withi~postle Islands National lakeshore National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center Ie PLEAS: I\ZTurm TO: TECHN1Cfil 1~!r-0:1MAT!O;l c::: :-:-:.::1 DENVC1 S:::;-:"":::: c;:::--;::1 ON M1CROF!Lf,l B&WScans r~i~TIO;~f~L f;~~:' ~Z~'J:C2 z .J'-t~ZO~5 -- --~~~------- ----~---- b - ----- ------------ THE ARCHEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION OF FOUR LIGHTHOUSE COMPLEXES AT THE WESTERN END OF LAKE SUPERIOR: THE 1988 TESTING PROGRAM WITHIN APOSTLE ISLANDS NATIONAL LAKESHORE By Vergil E. Noble Midwest Archeological Center Technical Report No.8 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska 1993 Ie ------ -- -- - -- --_.- - ----------------------------- --- ----- ABSTRACT During June and July of 1988, archeologists from the Midwest Archeological Center performed limited testing at four historic lighthouse complexes within Apostle Islands National Lakeshore. The lighthouses, which still protect shipping at the western end of Lake Superior, were scheduled for exterior restoration work. Specifically, immediate plans called for the installation of drainage systems about certain structures on Sand Island, Michigan Island, Outer Island, and Devils Island to mitigate continuing ground water damage to their foundations. Archeological investigations sought to assess the potential impacts to cultural resources in those areas of the light stations that would be disturbed by proposed developments. Shovel probes and controlled test excavations were used to examine the proposed drain alignments, as well as construction staging areas. No significant cultural resources were discovered during the five-week project that would warrant modification of the drainage systems or further archeological excavation prior to construction of these improvements. -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 ON THIS PAGE An opening in an ice-fringed sea cave reveals ice flows on Lake Superior. Photograph by Neil Howk (National Park Service) taken in winter 2008. ON THE COVER Wind and associated wave activity created a window in Devils Island Sandstone at Devils Island. Photograph by Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich (Colorado State University) taken in summer 2010. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR—2015/972 Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich Colorado State University Research Associate National Park Service Geologic Resources Division Geologic Resources Inventory PO Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225 May 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. The series supports the advancement of science, informed decision-making, and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series also provides a forum for presenting more lengthy results that may not be accepted by publications with page limitations. -

![Linn[Ae]An Society of New York](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9123/linn-ae-an-society-of-new-york-4539123.webp)

Linn[Ae]An Society of New York

x9 6 Sct'e•tlQfcSocz'elt'es. [April six have eight pairs. Of these six foul- have the extra pairofcostalarticu_ lations at the posterior end of the series while only t•vo have theadditional pair at the anterior extremity of the sternum. •oitwould seem that the chances offinding an extra pair of ribs connected with the sternum at the posterior end of the seriesare twice as great as of finding an extra pair so attached to the anterior portion ofl;he sternum, A portion of the definition of the super-family 31t'croibocloœcleawas acci- dentally omitted from mypapel-in the January Auk. This is. that of the six pairs ofribsall, save the first, articulate with the margin of the ster- num proper and not with the costalprocess. This seems to be a rather important character, as among the highly specialized Passeresthe ribs articulate exclusively with the costal process, while in more generalized forms, such as the water birds, the ribs articulate •vith the costalmargin of the sternum.--F. A. Lucas, V(as,•ing•ton,D.C. SCIENTIFIC SOCIETIES. Linnaean Society of New York. Tvm Society has issued no regular publications since August, •884, when Vol. II of the 'Transactions' xvas published. Many papers read before the Society have been printed in 'The Auk,' 'Forest and Stream, and elsewhere. The following is a r•snln• of the Proceedings for the officialyear •888-89. Asbrœl•3, •888.--Mr. Frank M. Chapman, Vice-President, in the chair. Mr.L.S. Foster presented a paper giving a chronological sketch of the life of John James Audubon. -

Apostle Islands Sea Kayaking

University of Minnesota Duluth – Recreational Sports Outdoor Program Apostle Islands Sea Kayaking Pick Your Dates HERE’S WHAT TO EXPECT: Explore More with RSOP: The freedom and excitement that Lake Superior sea kayaking offers is •Whitewater Kayak Courses something we’re thrilled to share with you! As a participant you will be actively involved and learning about equipment, paddling techniques, •Whitewater Canoe Courses navigation, on-water safety, and camping from sea kayaks. The itinerary will allow time to explore the natural features and cultural history of the •Rock Climbing on Minnesota’s Apostle Islands. North Shore WHO: •Rock Climbing Wall This trip is suited for all skill levels. Paddlers will be using a combination of single and tandem kayaks. •American Canoe Association Instructor Certification Workshops WHERE: Meet your instructors at the Little Sand Bay Visitor Center, Apostle Islands •Climbing Instructor Certifica- National Lakeshore or Red Cliff Casino. tion and Training Workshops COST: •Summer Youth Adventure $450/person/(2-3 people) Camps $425/person/(4-6 people) General Information and ITINERARY: Registration Phone: (218) 726-7128 As a participant, your abilities and expectations must be appropriate for the Fax: (218) 726-6767 following generalized conditions: Email [email protected] Website www.umdrsop.org 1. Lake Superior’s water temperature is in the fouties this time of year except for the shallow bays where water is warmed by the sun. A farmer Sea Kayaking Information john wetsuit and various poly-nylon layers, and a lifejacket will be worn at Call Pat Kohlin at 218-726-8801 all times. Weather and unforeseen group situations can create the need to alter our on-water activities. -

Town of Russell, Bayfield County, Wisconsin

Town of Russell 35900 State Highway 13 Bayfield, Wisconsin 54814 (715) 779-5338 or Fax (715) 779-0249 [email protected] www.townofrussell.org Paul “Rocky” Tribovich Judy Meierotto Dave Good Chairman Deputy Clerk/Treasurer Clerk/Treasurer TOWN BOARD MEETING 7 p.m. – Tuesday, September 11, 2018 Community Center 32500 W Old County K Road Any person wishing to attend who, because of a disability, requires special accommodations, should contact the Town Clerk at 715 779-5338, at least 24 hours before the scheduled meeting time, so appropriate arrangements can be made. 1. Call to order and roll call. 2. Pledge of Allegiance. 3. Approval of the agenda. 4. Public Input (3-minute limit-max 15 minutes total) at the beginning of the agenda. 5. Approval of the minutes of the August 21, 2018 Town Board Meeting Special Town Board/Roads Meeting of August 24, 2018****. OLD BUSINESS 6. Status of delivery of a new Town pick-up truck. 7. Proposal for a plow package for the new Town pick-up truck****. 8. Trade existing JD Loader and purchase of a 2018 JD Loader****. 9. Crack seal proposals for various blacktop roads****. a. Discussion regarding joint purchase of crack seal/patching equipment with Tribe. NEW BUSINESS 10. Propane proposals for 2018-2019 heating seasons****. 11. 2018-2019 driveway snow plowing rules & rates**** a. Driveways requiring maintenance in order for the Town to plow****. 12. Discussion and possible action regarding fund depository accounts****. STANDING AGENDA ITEMS 13. Road maintenance report and discussion. 14. Update on Town Land Development behind Community Center. -

A Wayside Exhibit Plan for Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

A WAYSIDE EXHIBIT PLAN FOR APOSTLE ISLANDS NATIONAL LAKESHORE by Paul Hlina ~I Graphic Images by: Sylvia Myhre and Greg Newell A Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE College of Natural Resources UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN Stevens Point, Wisconsin December, 1986 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Professor! Professor! "How many pages do I have to write in order to complete a Master's thesis project?" "Whatever it takes." "Is that all?" As pages began to accumulate in this project I realized the true impact of those words. For the last 2 years this project has been my life and work, but is not my work alone. In truth the project involved a collabora tion of minds that guided, advised, counseled and provided technical expertise when needed. Many thanks to Dr. Mike Gross, Dr. Randy Champeau, Mr. Ron Zimmerman, and Dr. Richard Geesey for their time and commitment in reviewing, editing, and commenting on the work. Their expertise and knowledge in effective environmental education and interpretation is found throughout the document. Also many thanks to the entire 1985 permanent and seasonal staff at the Apostle Islands National Lake shore. Not only was I provided with a place to live, but was made to feel welcome. In addition many workers went out of their way to transport me to islands or to locate an obscure government document. These indivi duals include: Jim Mack, . Chief Naturalist, Diane Keller, Assistant Chief Naturalist, Brent McGinn, Sea sonal District Ranger, Bill Ferraro, Chief Ranger Susan Brainard-Nelson, Seasonal Naturalist, Lydia Ferraro, Boat Operator, and Susan Monk, Park Historian. -

Historic Resource Study of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

People and Places: A Human History of the Apostle Islands Historic Resource Study of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Fred Hansen with grandson Fred Dahl, Sand Island, 1931. Courtesy of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, Alma Hansen Dahl Collection. Prepared under contract to: Midwest Regional Office, National Park Service United States Department of the Interior By Jane C. Busch, Ph.D. Omaha, 2008 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS …………………. v PREFACE ……………………………………………… vii Chapter One HISTORICAL OVERVIEW: NATURAL AND CULTURAL .. 1 Chapter Two NATIVE AMERICANS ………………………………….. 31 Chapter Three THE INTERNATIONAL FUR TRADE …………………… 73 Chapter Four SHIPPING AND LIGHTHOUSES ………………………… 111 Chapter Five COMMERCIAL FISHING ………………………………. 159 Chapter Six LOGGING ……………………………………………... 209 Chapter Seven QUARRYING …………………………………………... 245 Chapter Eight FARMING ……………………………………………… 267 Chapter Nine TOURISM AND RECREATION …………………………. 299 MAPS ………………………………………………….. 349 BIBLIOGRAPHY ……………………………………….. 363 INDEX …………………………………………………. 373 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 Lac Superieur by Claude Dablon and Claude Allouez, 1672 ……… 12 Figure 2 American Fur Company map of the Apostle Islands, 1839 ………... 16 Figure 3 Chief Buffalo ……………………………………………………….. 50 Figure 4 Annuity payment at Bad River, 1870 ………………………………. 63 Figure 5 Artifacts from the Winston-Cadotte site, Madeline Island………… 88 Figure 6 View of La Pointe, ca. 1843 ………………………………………... 104 Figure 7 Devils Island light station, ca. 1903 ………………………………... 130 Figure 8 Garden at Raspberry Island light station …………………………… 142 Figure 9 Ed Lane’s family at old Michigan Island lighthouse, 1910–15 ……. 144 Figure 10 Sand Island lighthouse in winter, before 1921 ……………………... 146 Figure 11 Hokenson brothers lifting pound nets, 1938 ……………………….. 182 Figure 12 Burt and Anna Mae Hill, Sand Island, ca. 1930s …………………... 189 Figure 13 Fred Hansen at the Boar’s Nest, Sand Island, ca. -

Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study

Social Science Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study Summer 2004 Report 157 Park Studies Unit Social Science Program National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Visitor Services Project Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Visitor Study Summer 2004 Margaret A. Littlejohn Steven J. Hollenhorst Visitor Services Project Report 157 April 2005 Margaret Littlejohn is the National Park Service VSP Coordinator and Dr. Steven Hollenhorst is the Director of the Park Studies Unit, Department of Conservation Social Sciences, University of Idaho. We thank Yen Le, Pixie Siebe, and the staff and volunteers of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore for their assistance with this study. The VSP acknowledges the Public Opinion Lab of the Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Washington State University, for its technical assistance. Apostle Islands National Lakeshore VSP Visitor Study July 24-August 1, 2004 Visitor Services Project Apostle Islands National Lakeshore Report Summary ! This report describes the results of a visitor study at Apostle Islands National Lakeshore (NL) during July 24 - August 1, 2004. A total of 671 questionnaires were distributed to visitor groups. Visitor groups returned 505 questionnaires for a 75% response rate. ! This report profiles Apostle Islands NL visitors. A separate appendix contains visitors’ comments about their visit. This report and the appendix include summaries of those comments. ! Forty percent of visitor groups had two people, 28% had three or four people, and 22% had six or more people. Many visitor groups consisted of family (47%) and friends (24%). Fifty-nine percent of visitors were ages 36-60 years and 11% were ages 15 years or younger. -

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Rocky Island, Wisconsin

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR ROCKY ISLAND QUADRANGLE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WISCONSIN-ASHLAND CO. 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 90°45' 42'30" 40' 90°37'30" 6 000m 6 6 6 6 6 6 1 810 000FEET 47°07'30" 71 E 72 73 75 76 78 79 47°07'30" 5221000mN 5221 710 000 5220 FEET 5220 5219 5219 5218 5218 Imagery................................................NAIP, January 2010 Roads..............................................©2006-2010 Tele Atlas Names...............................................................GNIS, 2010 5' 5' Hydrography.................National Hydrography Dataset, 2010 Contours............................National Elevation Dataset, 2010 5217 5216 Devils ―│ Island │ ― ―│ Shoal │ ― 10 │ 52 │ ― │ ― ― ―│ 16 │ ― ―│ T53N R3W │ ― ―│ │ ― │ │ ― │ Devils ― ― │ ― Island―│ │ ― ―│ │ ― │ │ ― ― ―│ │ ― ―│ AINL 650 5215 15 5215 5214 5214 17 18 20 ―│ T53N │ LAKE SUPERIOR ― ―│ ―│ R2W │ 52 │ 13 ― ― ―│ ―│ │ 650 ― 19│ ― ―│ 52 ―│ 13 ―│ │ 650 ― 2'30" │ 2'30" 24 ― ―│ │ ― ―│ ―│ │ 52 ― ―│ 12 Rocky―│ 20 │ │ ― Island― ―│ │ ― │ │ ― │ ― ― ―│ │ ― ―│ 52 12 │ ― ―│ ―│ │ ― │ ― │ ― ―│ │ ― ―│ T53N R3W South │ ― ―│ Twin ―│ T53N R2W │ 25 ― ―│ Island │ 30― ―│ 29 APOSTLE ISLANDS NATIONAL LAKESHORE 5211 ―│ 700 AINL ―│ ―│ ―│ 52 │ │ ― ― 650 11 650 ―│ 28 │ ― ―│ │ 28 │ ― ― ―│ │ ― ―│ │ ― ―│ │ ― ―│ 36 ―│ │ │ 5210― ― ―│ │ │ │ │ ― ― ― │ │ ― ― │ ― ― │ │ │ ― │ │ ― ― ― ― │ │ ― │ │ ― │ ― │ │ ― ― │ ― ― ― 52 │ │ │ │ ― ― ― │ 10 │ ― ― │ ― ― │ │ 33 │ ― │ │ ― ― ― ― │