Conversations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

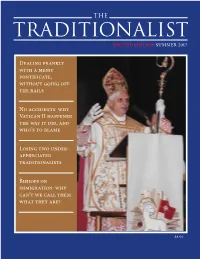

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Branson-Shaffer-Vatican-II.Pdf

Vatican II: The Radical Shift to Ecumenism Branson Shaffer History Faculty advisor: Kimberly Little The Catholic Church is the world’s oldest, most continuous organization in the world. But it has not lasted so long without changing and adapting to the times. One of the greatest examples of the Catholic Church’s adaptation to the modernization of society is through the Second Vatican Council, held from 11 October 1962 to 8 December 1965. In this gathering of church leaders, the Catholic Church attempted to shift into a new paradigm while still remaining orthodox in faith. It sought to bring the Church, along with the faithful, fully into the twentieth century while looking forward into the twenty-first. Out of the two billion Christians in the world, nearly half of those are Catholic.1 But, Vatican II affected not only the Catholic Church, but Christianity as a whole through the principles of ecumenism and unity. There are many reasons the council was called, both in terms of internal, Catholic needs and also in aiming to promote ecumenism among non-Catholics. There was also an unprecedented event that occurred in the vein of ecumenical beginnings: the invitation of preeminent non-Catholic theologians and leaders to observe the council proceedings. This event, giving outsiders an inside look at 1 World Religions (2005). The Association of Religious Data Archives, accessed 13 April 2014, http://www.thearda.com/QuickLists/QuickList_125.asp. CLA Journal 2 (2014) pp. 62-83 Vatican II 63 _____________________________________________________________ the Catholic Church’s way of meeting modern needs, allowed for more of a reaction from non-Catholics. -

The Death of a Pope Reading and Discussion Guide

The Death of a Pope Reading and Discussion Guide About The Death of a Pope The Death of a Pope is a fast-paced theological thriller set in London, Rome and Africa during the last months of the pontificate of Pope John Paul II. A former Jesuit, Juan Uriarte, working for a Catholic relief agency, Misericordia, is looking for a supply of poison gas. For what purpose? Can we take at face value his own explanation? Why did he leave the priesthood? What are his present beliefs about the state of the Catholic Church? Three quotations appear as epigraphs to The Death of a Pope and set the context for the ideas treated in the drama. The first is from Pope Benedict XVI, reminding us that Jesus was not Spartacus - `he was not engaged in a fight for political liberation’. The second is from the theologian Hans Küng, ISBN: 9781586172954 denouncing the system whereby conservative popes appoint See more: ipnovels.com/novels/the-death-of-a- conservative cardinals who will ensure the election of a pope/ conservative successor. The third is from the British journalist Polly Toynbee who, in her column in the Guardian in 2002, stated that `the Pope kills millions through his reckless spreading of AIDS’. However, the story involves more than ideas. We learn about the inner workings of the Curia in Rome, and the British secret service; and we share the human emotions of the diverse characters involved - a young journalist, Kate Ramsey; a British secret agent, David Kotovski; a Catholic priest, Father Luke Scott; a Dutch Curial Cardinal, Cardinal Doornik; his secretary, Mosignor Doornik; and finally the charismatic aid worker, Juan Uriarte. -

VATICAN II and NEW THINKING ABOUT CATHOLIC EDUCATION: AGGIORNAMENTO THINKING and PRINCIPLES INTO PRACTICE Gerald Grace Centre F

‘Copies can also be obtained from Professor Grace at CRDCE, St. Mary’s Catholic University, Waldegrave Road, Twickenham TW1 4SX’. VATICAN II AND NEW THINKING ABOUT CATHOLIC EDUCATION: AGGIORNAMENTO THINKING and PRINCIPLES INTO PRACTICE Gerald Grace Centre for Research and Development in Catholic Education (CRDCE) St. Mary’s University, Twickenham, London UK. Chapter for: New Thinking about Catholic Education (Ed). S. Whittle Routledge, 2016 Note on Contributor Gerald Grace has researched and written widely on Catholic education. His latest book, Faith, Mission and Challenge in Catholic Education has been published by Routledge in the World Library of Educationalists Series (2016) Part 1: Historical Background INTRODUCTION : Gravissimum Educationis, ‘a rather weak document’ (Ratzinger, 1966) Gravissimum Educationis (1965) failed to excite much interest and discussion at the time of its publication and subsequent comment upon it has been generally critical. Thus we find Professor Alan McClelland (1991) describing it as ‘somewhat uninspiring and, in places almost platitudinous’ (p.172). In a later scholarly paper entitled, ‘Toward a Theology of Catholic Education’ (1999), Dr.Brian Kelty lamented the fact that Gravissimum Educationis largely repeated the teaching of Pius XI that Christian education should be seen as ‘preparation for eternal life in the world to come’ (p.11), (an entirely proper and classic Catholic understanding), but failed to develop thinking about, ‘preparing people capable of working for the transformation of this world’ (p.13). Perhaps the most influential judgment on the document had already been made by Professor Joseph Ratzinger in his book, Theological Highlights of Vatican II (1966) in which he described the Decree on Christian Education as ‘ unfortunately, a rather weak document’ (p.254). -

1 Curriculum Vitae Francis X. Clooney, S.J. Parkman Professor of Divinity

Curriculum Vitae Francis X. Clooney, S.J. Parkman Professor of Divinity and Professor of Comparative Theology Director of the Center for the Study of World Religions Harvard Divinity School 45 Francis Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 384-9396 [email protected] http://www.hds.harvard.edu/faculty/clooney.cfm Educational Data 1984 Ph.D., University of Chicago, Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations 1978 M.Div., Weston School of Theology; with distinction 1973 B.A., Fordham University; Summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa Honorary Doctorates College of the Holy Cross, 2011 Australian Catholic University, 2012 Corresponding Fellow, British Academy, 2010- Memberships and Editorial Boards American Academy of Religion Board of Directors, 2003-2008 Executive Committee, 2005-2006 Chair, Publications Committee, 2003-2005 Hinduism Group, Steering Committee, 2003-2005 Comparative Theology Group, Founder and Member, 2006- American Theological Society, 1998- Boston Theological Society, 1984- Catholic Theological Society of America; Board of Directors (2001-2003) Center for Faith and Culture at Saint Michael's College (Vermont), 2005- 1 Coordinator for Interreligious Dialogue, Society of Jesus, United States, 1998-2004; National Dialogue Advisory Board, Society of Jesus, 2005-9 Dilatato Corde, Editorial Board, 2010- European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Editorial Board, 2007- International Journal of Hindu Studies, Editorial Board International Society for Hindu-Christian Studies: First President, 1994-1996; Chair, Book Committee, -

Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs

2007–2008 ANNUAL REPORT GEORGETOWN UNIVERSITY Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs “At Georgetown University we have long recognized the necessity of building bridges of understanding between faiths and cultures. Through the Berkley Center, we bring together intellectual leaders and the public to provide knowledge, inform debate, and promote greater dialogue across religious traditions.” Georgetown University President Dr. John J. DeGioia CENTER HigHLigHTs ....................................... 2 COLLABORATiVE PARTNERs ............................... 3 PROgRAMs • RELigiOUs PluralisM ANd WORLd AffAiRs ......... 4 • GlobalizatiON, RELigiONs, ANd THE sECULAR ..... 8 • RELigiON ANd Us fOREigN POLiCy ................... 10 • THE CHURCH ANd iNTERRELigiOUs dialogUE ....... 12 • RELigiON, POLiTiCs, ANd Law ........................ 14 • RELigiON ANd Global Development ............... 16 UNdERgRAduate iNiTiatiVEs ............................. 18 DatabasEs................................................. 20 PEOPLE..................................................... 22 2007— 2008 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Center Highlights The force of religion in contemporary world affairs demands knowledge, dialogue, and action. Religion’s role in national and international politics remains poorly understood. Commu- nication across traditions is difficult. Yet religious communities have unmet potential in the struggle against violence, injustice, poverty, and disease around the world. Through research, teaching, and outreach activities, the Berkley Center -

Church As Christ's Sacrament and the Spirit's

THE TRINITARIAN FORM OF THE CHURCH: CHURCH AS CHRIST’S SACRAMENT AND THE SPIRIT’S LITURGY OF COMMUNION Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Robert Mark Zeitzmann, B.A. Dayton, Ohio August 2021 THE TRINITARIAN FORM OF THE CHURCH: CHURCH AS CHRIST’S SACRAMENT AND THE SPIRIT’S LITURGY OF COMMUNION Name: Zeitzmann, Robert Mark APPROVED BY: ________________________________________________ Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ________________________________________________ Elizabeth Groppe, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ________________________________________________ William H. Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ________________________________________________ Jana Bennett, Ph.D. Chairperson ii © Copyright by Robert Mark Zeitzmann All rights reserved 2021 iii ABSTRACT THE TRINITARIAN FORM OF THE CHURCH: CHURCH AS CHRIST’S SACRAMENT AND THE SPIRIT’S LITURGY OF COMMUNION Name: Zeitzmann, Robert Mark University of Dayton Advisor: Dennis M. Doyle, Ph.D. This thesis argues that the Western sacramental and christological ecclesiology of Otto Semmelroth, SJ, is complementary with the Eastern pneumatological-trinitarian theology of liturgy of Jean Corbon, OP. Their little studied theologies are taken as key for interpreting and receiving the Second Vatican Council. Where Semmelroth had a distinct and influential impact on Vatican II’s sacramental ecclesiology, particularly in Lumen Gentium, Corbon had a similar impact on the theology of liturgy of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. A particular point of significance of Vatican II is its personalist paradigm shift of recentering the faith of the church on God’s revelation of self as Trinity of persons. -

Envisioning Catholicism: Popular Practice of a Traditional Faith in the Post-Wwii Us

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2020 ENVISIONING CATHOLICISM: POPULAR PRACTICE OF A TRADITIONAL FAITH IN THE POST-WWII US Christy A. Bohl University of Kentucky, [email protected] Author ORCID Identifier: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0884-2280 Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.497 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Bohl, Christy A., "ENVISIONING CATHOLICISM: POPULAR PRACTICE OF A TRADITIONAL FAITH IN THE POST-WWII US" (2020). Theses and Dissertations--History. 64. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/64 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Mary, the Us Bishops, and the Decade

REVEREND MONSIGNOR JOHN T. MYLER MARY, THE U.S. BISHOPS, AND THE DECADE OF SILENCE: THE 1973 PASTORAL LETTER “BEHOLD YOUR MOTHER WOMAN OF FAITH” A Doctoral Dissertation in Sacred Theology in Marian Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Sacred Theology DIRECTED BY REV. JOHANN G. ROTEN, S.M., S.T.D. INTERNATIONAL MARIAN RESEARCH INSTITUTE UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON DAYTON, OHIO July 19, 2017 Mary, The U.S. Bishops, and the Decade of Silence: The 1973 Pastoral Letter “Behold Your Mother Woman of Faith” © 2017 by Reverend Monsignor John T. Myler ISBN: 978-1-63110-293-6 Nihil obstat: Francois Rossier, S.M.. STD Vidimus et approbamus: Johann G. Roten, S.M., PhD, STD – Director Bertrand A. Buby, S.M., STD – Examinator Thomas A. Thompson, S.M., PhD – Examinator Daytonensis (USA), ex aedibus International Marian Research Institute, et Romae, ex aedibus Pontificiae Facultatis Theologicae Marianum die 19 Julii 2014. All Rights Reserved Under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Printed in the United States of America by Mira Digital Publishing Chesterfield, Missouri 63005 For my Mother and Father, Emma and Bernard – my first teachers in the way of Faith… and for my Bishops, fathers to me during my Priesthood: John Nicholas, James Patrick, Wilton and Edward. Abbreviations Used CTSA Catholic Theological Society of America DVII Documents of Vatican II (Abbott) EV Evangelii Nuntiandi LG Lumen Gentium MC Marialis Cultus MS Marian Studies MSA Mariological Society of America NCCB National Conference of Catholic Bishops NCWN National Catholic Welfare Conference PL Patrologia Latina SC Sacrosanctam Concilium USCCB United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Contents Introduction I. -

The Catholic Church and the Turn of the 20Th Century: an Anthropology of Human Flourishing and a Church for Peace

College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses School of Theology and Seminary January 2020 The Catholic Church and the Turn of the 20th Century: An Anthropology of Human Flourishing and a Church for Peace Maria Siebels College of Saint Benedict and Saint John's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Siebels, Maria, "The Catholic Church and the Turn of the 20th Century: An Anthropology of Human Flourishing and a Church for Peace" (2020). School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses. 1923. https://digitalcommons.csbsju.edu/sot_papers/1923 This Graduate Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Theology and Seminary at DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Theology and Seminary Graduate Papers/Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@CSB/SJU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Siebels The Catholic Church and the Turn of the 20th Century: An Anthropology of Human Flourishing and a Church for Peace By: Maria Siebels A Paper Submitted to the Faculty of the School of Theology and Seminary of Saint John’s University, Collegeville, Minnesota, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Theological Studies SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND SEMINARY Saint John’s University Collegeville, Minnesota 3/22/19 1 Siebels This paper was written under the direction of 2 Siebels The Catholic Church and the Turn of the 20th Century: An Anthropology of Human Flourishing and a Church for Peace Description: This paper will explore the connections between the 20th century’s unsurpassed violence and the Catholic Church’s adoption of anthropology of human dignity and flourishing, resulting in a call and commission for peace as seen in Pacem et Terris, Gaudium et Spes, and the Catholic Worker Movement. -

Introduction 1. for Examples of These Types of Media Stories, See Joseph Berger, “Interfaith Marriages Stir Mixed Feelings, T

Notes Introduction 1. For examples of these types of media stories, see Joseph Berger, “Interfaith Marriages Stir Mixed Feelings,” The New York Times (Aug. 4, 2010), http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/04 /us/04interfaith.html?_r=1, accessed Aug. 4, 2010; Marion L. Usher, “Chelsea Clinton and Marc Mezvinsky: Religion and Interfaith Marriage,” The Washington Post , (Aug. 4, 2010), http:// newsweek.washingtonpost.com/onfaith/guestvoices/2010/07 /chelsea_clinton_and_marc_mezvinsky_religion_and_interfaith _marriage.html?hpid=talkbox1, accessed Aug. 10, 2010. 2. These observations are based upon a cursory analysis of blogs from people commenting on the news regarding the Clinton-Mezvinsky marriage. 3. See Richard Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 1–22. 4. See Alex B. Leeman, “Interfaith Marriage in Islam: An Examination of the Legal Theory Behind the Traditional and Reformist Positions,” Indiana Law Journal (Spring 2009): 743–771. 5. See Dana Lee Robert, Christian Mission: How Christianity Became a World Religion (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009); Hugh McLeod, ed., World Christianities (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006). 6. I use the term “religious intermarriage” broadly and generically to refer to interreligious, interfaith, mixed, and/or exogamous mar- riage—terms widely used to refer to the phenomenon of marriage between individuals who identify with different religious beliefs and practices. 7. Maurice Fishberg, Jews, Race, and Environment (New Brunswick, NJ: Translation Publishers, 2006, c.1911), 221; Paul R. Spickard, Mixed Blood: Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 165. 174 NOTES 8. James A. Brundage, Sex, Law, and Marriage in the Middle Ages (Brookfield, VT: Variorum/Ashgate Publishing Company, 1993), 26–27. -

Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Dissertations (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia Shaun London Blanchard Marquette University Recommended Citation Blanchard, Shaun London, "Eighteenth-Century Forerunners of Vatican II: Early Modern Catholic Reform and the Synod of Pistoia" (2018). Dissertations (2009 -). 774. https://epublications.marquette.edu/dissertations_mu/774 EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA by Shaun L. Blanchard, B.A., MSt. A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Milwaukee, Wisconsin May 2018 ABSTRACT EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY FORERUNNERS OF VATICAN II: EARLY MODERN CATHOLIC REFORM AND THE SYNOD OF PISTOIA Shaun L. Blanchard Marquette University, 2018 This dissertation sheds further light on the nature of church reform and the roots of the Second Vatican Council (1962–65) through a study of eighteenth-century Catholic reformers who anticipated Vatican II. The most striking of these examples is the Synod of Pistoia (1786), the high-water mark of “late Jansenism.” Most of the reforms of the Synod were harshly condemned by Pope Pius VI in the Bull Auctorem fidei (1794), and late Jansenism was totally discredited in the increasingly ultramontane nineteenth-century Catholic Church. Nevertheless, many of the reforms implicit or explicit in the Pistoian agenda – such as an exaltation of the role of bishops, an emphasis on infallibility as a gift to the entire church, religious liberty, a simpler and more comprehensible liturgy that incorporates the vernacular, and the encouragement of lay Bible reading and Christocentric devotions – were officially promulgated at Vatican II.