The Life and Death of King Iohn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Bale's <I>Kynge Johan</I> As English Nationalist Propaganda

Quidditas Volume 35 Article 10 2014 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George's County Public Schools, Prince George's Community College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation George, G. D. (2014) "John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda," Quidditas: Vol. 35 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol35/iss1/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Quidditas 35 (2014) 177 John Bale’s Kynge Johan as English Nationalist Propaganda G. D. George Prince George’s County Public Schools Prince George’s Community College John Bale is generally associated with the English Reformation rather than the Tudor government. It may be that Bale’s well-know protestant polemics tend to overshadow his place in Thomas Cromwell’s propaganda machine, and that Bale’s Kynge Johan is more a propaganda piece for the Tudor monarchy than it is just another of his Protestant dramas.. Introduction On 2 January, 1539, a “petie and nawghtely don enterlude,” that “put down the Pope and Saincte Thomas” was presented at Canterbury.1 Beyond the fact that a four hundred sixty-one year old play from Tudor England remains extant in any form, this particular “enterlude,” John Bale’s play Kynge Johan,2 remains of particular interest to scholars for some see Johan as meriting “a particular place in the history of the theatre. -

King John Take Place in the Thirteenth Century, Well Before Shakespeare’S Other English History Plays

Folger Shakespeare Library https://shakespeare.folger.edu/ Get even more from the Folger You can get your own copy of this text to keep. Purchase a full copy to get the text, plus explanatory notes, illustrations, and more. Buy a copy Contents From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library Front Textual Introduction Matter Synopsis Characters in the Play ACT 1 Scene 1 ACT 2 Scene 1 Scene 1 Scene 2 ACT 3 Scene 3 Scene 4 Scene 1 ACT 4 Scene 2 Scene 3 Scene 1 Scene 2 Scene 3 ACT 5 Scene 4 Scene 5 Scene 6 Scene 7 From the Director of the Folger Shakespeare Library It is hard to imagine a world without Shakespeare. Since their composition four hundred years ago, Shakespeare’s plays and poems have traveled the globe, inviting those who see and read his works to make them their own. Readers of the New Folger Editions are part of this ongoing process of “taking up Shakespeare,” finding our own thoughts and feelings in language that strikes us as old or unusual and, for that very reason, new. We still struggle to keep up with a writer who could think a mile a minute, whose words paint pictures that shift like clouds. These expertly edited texts are presented to the public as a resource for study, artistic adaptation, and enjoyment. By making the classic texts of the New Folger Editions available in electronic form as The Folger Shakespeare (formerly Folger Digital Texts), we place a trusted resource in the hands of anyone who wants them. -

Understanding Shakespeare's King John and Magna Carta in the Light

Bilgi [2018 Yaz], 20 [1]: 241-259 Understanding Shakespeare’s King John and 1 Magna Carta in the Light of New Historicism Kenan Yerli2 Abstract: Being one of the history plays of William Shakespeare, The Life and Death of King John tells the life and important polit- ical matters of King John (1166-1216). In this play, Shakespeare basically relates the political issues of King John to Queen Eliza- beth I. Political matters such as the threat of invasion by a foreign country, divine right of kings; papal excommunication and legit- imacy discussions constitute the main themes of the play. How- ever, Shakespeare does not mention a word of Magna Carta throughout the play. In this regard, it is critical to figure out and explain the reason why Shakespeare did not mention Magna Car- ta in his The Life and Death of King John, owing to the im- portance of Magna Carta in the history of England. In this respect, the analysis of The Life and Death of King John in the light of new historicism helps us to understand both how Shakespeare re- lated the periods of Queen Elizabeth and King John; and the rea- son why Shakespeare did not mention Magna Carta in his play. Keywords: Shakespeare, New Historicism, Magna Carta, Eliza- bethan Drama. 1. This article has been derived from the doctoral dissertation entitled Political Propaganda in Shakespeare’s History Plays. 2. Sakarya University, School of Foreign Languages. 242 ▪ Kenan Yerli Being one of the most important playwrights of all times, William Shakespeare wrote and staged great number of plays about English history. -

King John Article (Cathleen Sheehan)

The Historical King John By Cathleen Sheehan, Dramaturg Today, King John is a little-known historical figure. If you are a student of history, you might connect him to the Magna Carta; if you are a student of romance literature (or Disney films), you might recognize him as the nemesis of Robin Hood. For Shakespeare’s contemporaries, however, King John was a compelling figure—a complicated king whose reign resonated with the anxieties of the day. In King John, Shakespeare addresses the fears of England as a land of civil disputes, subject to foreign invasion and Papal interference. The most pressing and controversial issues in the play are questions of succession and legitimacy. Shakespeare used several sources for the story—relying predictably on Holinshed, the official Tudor chronicler, as well as John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments. As always, Shakespeare’s adaptation of historical facts—or what were taken to be facts—reveals his thematic and dramatic intentions. The play opens in roughly 1199 with the French making gestures of aggression toward King John. France disputes John’s right to be king—backing instead his nephew Arthur, the son of John’s older brother Geoffrey. Presumably, King Philip of France likes the thought of a French-raised, very young king in England—a king who might be easy to influence and more favorably inclined toward France. And Arthur’s claim to the throne is not so easily dismissed, as John’s mother even admits. Arthur’s claim pits inheritance by primogeniture against inheritance by will—a pertinent tension in Shakespeare’s day. -

John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation

Durham E-Theses John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation ROYAL, SUSAN,ANN How to cite: ROYAL, SUSAN,ANN (2014) John Foxe's 'Acts and Monuments' and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10624/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 John Foxe's Acts and Monuments and the Lollard Legacy in the Long English Reformation Susan Royal A Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Durham University Department of Theology and Religion 2013 Abstract This thesis addresses a perennial historiographical question of the English Ref- ormation: to what extent, if any, the late medieval dissenters known as lollards influenced the Protestant Reformation in England. To answer this question, this thesis looks at the appropriation of the lollards by evangelicals such as William Tyndale, John Bale, and especially John Foxe, and through them by their seven- teenth century successors. -

Review Essay

Early Theatre 16.1 (2013), 151–75 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12745/et.16.1.9 Review Essay Kent Cartwright Defining Tudor Drama The gods are smiling upon the field of Tudor literature — perhaps to para- doxical effect, as we shall later see. In 2009 Oxford University Press published Mike Pincombe and Cathy Shrank’s magnificent (and award-winning) col- lection of multi-authored essays The Oxford Handbook of Tudor Literature.1 For drama specialists, Oxford has now followed it with Thomas Betteridge and Greg Walker’s The Oxford Handbook of Tudor Drama.2 This fresh atten- tion to Tudor literature has surely received encouragement from scholarly interest in political history and in religious change during the sixteenth century in England, as illustrated in drama studies by the transformational influence of, for example, Paul Whitfield White’s 1993 Theatre and Reforma- tion: Protestantism, Patronage and Playing in Tudor England. The important Records of Early English Drama project, now almost four decades old, has bolstered such interests.3 More recently, Tudor literature has figured in the ongoing reconsideration of a reigning theory of literary periodization that segmented off what was ‘medieval’ from what was ‘Renaissance’; that recon- sideration, well under way, now tracks the long reach of medieval values and worldviews into the 1530s and beyond. Tudor literary studies has received impetus, too, from the tireless efforts of a number of eminent scholars. Greg Walker, the co-editor of the Handbook, for instance, has authored a series of books on Tudor drama (and most recently Tudor literature) that display a fine-grained, locally attuned, paradigm-setting political analysis at a level never before achieved. -

The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88632-1 - The New Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Margreta De Grazia and Stanley Wells Index More information INDEX Note: Page numbers for illustrations are given in italics. Works by Shakespeare appear under title; works by others under author’s name. 4D art: La Tempête 296 , 297 language 83–4 , 86 , 202 , 203 , 208 performance 52 , 333 actor-managers 287 sexuality and gender 221 actors apprentices 45–6 actions and feelings 194–5 Arabic performances 297–8 globalization 287–91 Archer, William 236 performance 233–8 , 248–9 , 287–8 Arden, Mary ( later Shakespeare) xiv , in Shakespeare’s London 45–9 , 61 4 , 5 see also boy actors Arden, Robert 4 , 5 Adams, W. E. 68 ‘Arden Shakespeare’ 69 , 73 , 83 , 255 , 292 , Addison, Joseph 80–1 326 Adelman, Janet Ariosto, Ludovico: Orlando Furioso 92 Hamlet to the Tempest 338 Aristotle 88 , 122 , 128 , 138 Suffocating Mothers: Fantasies of Armin, Robert 46 , 98 Maternal Origin in Shakespeare’s art 339 Plays 338 As You Like It xv , 62 , 114–15 Aesop: Fables 19 categorization 171 Afghanistan 289–90 , 294 characters 46 Age of Kings, An (BBC mini-series) 313 language 17 Akala 280–1 plot devices 109 , 173 Al-Bassam, Sulayman: Richard III – An Arab sexuality and gender 218 , 219 , 223–4 Tragedy 297–8 sources 23 Alexander, Shelton 280 theatre 51 , 52 All is True see Henry VIII Ascham, Roger: The Scholemaster 18 , 20 , Allen, A. J. B. 327 22–3 Allot, Robert: England’s Parnassus 91 Aubrey, John 8 All’s Well That Ends Well xvi , 62 , 84 , audiences 116–17 , 122 , 199 , 213 , 219 audience agency 316–17 Almereyda, Michael: Hamlet 318 , 319–21 , early modern popular culture 271–3 , 274 320 media history 315–17 Amyot, Jacques 20 authors and authorship 1 , 32–4 , 61–2 , 97 , Andrews, John F.: William Shakespeare: His 291–5 , 308 World, His Work, His Infl uence 328 Autran, Paulo 290–1 anti-Stratfordianism 273 Antony and Cleopatra xvi , 62 , 162–3 Bacon, Francis 128 actors 46 Bakhtin, Michaïl 275 characters 163 , 274 Baldwin, T. -

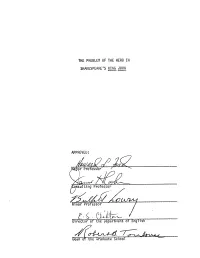

THE PROBLEM of the HERO in SHAKESPEARE's KING JOHN APPROVED: R Professor Suiting Professor Minor Professor Partment of English

THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN APPROVED: r Professor / suiting Professor Minor Professor l-Q [Ifrector of partment of English Dean or the Graduate School THE PROBLEM OF THE HERO IN SHAKESPEARE'S KING JOHN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Wilbert Harold Ratledge, Jr., B. A. Denton, Texas June, 1970 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE MILIEU OF KING JOHN 7 III. TUDOR HISTORIOGRAPHY 12 IV. THE ENGLISH CHRONICLE PLAY 22 V. THE SOURCES OF KING JOHN 39 VI. JOHN AS HERO 54 VII. FAULCONBRIDGE AS HERO 67 VIII. ENGLAND AS HERO 82 IX. WHO IS THE VILLAIN? 102 X. CONCLUSION BIBLIOGRAPHY 118 in CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION During the last twenty-five years Shakespeare scholars have puolished at least five major works which deal extensively with Shakespeare's history plays. In addition, many critical articles concerning various aspects of the histories have been published. Some of this new material reinforces traditional interpretations of the history plays; some offers new avenues of approach and differs radically in its consideration of various elements in these dramas. King John is probably the most controversial of Shakespeare's history plays. Indeed, almost everything touching the play is in dis- pute. Anyone attempting to investigate this drama must be wary of losing his way among the labyrinths of critical argument. Critical opinion is amazingly divided even over the worth of King John. Hardin Craig calls it "a great historical play,"^ and John Masefield finds it to be "a truly noble play . -

Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Shaun Stiemsma Washington, DC 2017 Dramatic Form in the Early Modern English History Play Shaun Stiemsma, Ph.D. Director: Michael Mack, Ph.D. The early modern history play has been assumed to exist as an independent genre at least since Shakespeare’s first folio divided his plays into comedies, tragedies, and histories. However, history has never—neither during the period nor in literary criticism since—been satisfactorily defined as a distinct dramatic genre. I argue that this lack of definition obtains because early modern playwrights did not deliberately create a new genre. Instead, playwrights using history as a basis for drama recognized aspects of established genres in historical source material and incorporated them into plays about history. Thus, this study considers the ways in which playwrights dramatizing history use, manipulate, and invert the structures and conventions of the more clearly defined genres of morality, comedy, and tragedy. Each chapter examines examples to discover generic patterns present in historical plays and to assess the ways historical materials resist the conceptions of time suggested by established dramatic genres. John Bale’s King Johan and the anonymous Woodstock both use a morality structure on a loosely contrived history but cannot force history to conform to the apocalyptic resolution the genre demands. -

University of Nevada, Reno John Bale and the National Identity And

University of Nevada, Reno John Bale and the National Identity and Church of Tudor England A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English by Mark Farnsworth Dr. Eric Rasmussen/Dissertation Advisor May, 2014 © by Mark David Farnsworth 2014 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the dissertation prepared under our supervision by MARK FARNSWORTH entitled John Bale and the National Identity and Church of Tudor England be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Eric Rasmussen, Ph. D., Advisor James Mardock, Ph. D., Committee Member Dennis Cronan, Ph. D., Committee Member Kevin Stevens, Ph. D., Committee Member Linda Curcio, Ph. D., Graduate School Representative David Zeh, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School May, 2014 i Abstract Although some of John Bale’s works seemed disconnected from contemporary events of his time (including his Biblical plays, bibliographic histories, and exegetical works), this dissertation contends that he took a highly active role in seeking to guide and influence England’s national and political identity. Bale saw himself as a divinely called messenger to the monarch, to fellow preachers and writers, and to all Britons. King Johan , Bale’s most famous play, demonstrated themes common in Bale’s work, including the need for Biblical religion, the importance of British political and religious independence, and the leading role of the monarch in advancing these religious and political ideals. Bale depicted the ruler as having the ability to build on England’s heritage of historical goodness and bring about its righteous potential. -

The Historical Evolution of the Death of King John in Three Renaissance Plays

Quidditas Volume 3 Article 8 1982 The Historical Evolution of the Death of King John in Three Renaissance Plays Carole Levin University of Iowa Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Levin, Carole (1982) "The Historical Evolution of the Death of King John in Three Renaissance Plays," Quidditas: Vol. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol3/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Historical Evolution of the Death of King John in Three Renaissance Plays* by Carole Levin University of Iowa Although King John died of dysentery in 1216, three Renaissance dramas, John Bale's King Johan, The Troublesome Reign of King John, and Shakespeare's King John, reflect the influence of late medieval leg ends that John was dramatically poisoned. Bale and the anonymous author of The Troublesome Reign emphasize the horror of the king's death, dwelling upon his role as a religious leader; Shakespeare, however, sepa rates John from the kingship, focusing our attention upon a frightened man. This separation echoes the medieval political theory that the king ship is composed of two bodies.' By deliberately stripping away the Chris tian images that surround John's death in the earlier plays, Shakespeare establishes a contrast between John the man (the body natural) and the ideal of kingship (the body politic), the patriotic ideal enunciated by Faul conbridge. -

John Bale, William Shakespeare, and King John

John Bale, William Shakespeare, and King John By Mark Stevenson For Les Fairfield Christmastide, 1538-1539 must have been extraordinarily busy for the priest- playwright John Bale. Already deeply enmeshed in the intrigues and stratagems of the volatile religious and political atmosphere of the time, this Christmas season found Bale in the service of Thomas Cromwell, the “mother and midwife of the English Reformation” (House 123). As an active member of Cromwell’s stable of propagandists, Bale and his peripatetic troupe of actors might very well have found themselves performing a command holiday performance of Bale’s provocative play King John at Canterbury in the presence of Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer himself. 1 Bale’s play represents one of the high points in the astonishing rehabilitation of the reputation of King John, who at the time of the Canterbury performance had been dead for more than 300 years. The emergence of King John Lackland (reigned 1199-1216) as Protestant hero and martyr might seem curious, even grotesque. He had, after all, capitulated to the intense pressure of Pope Innocent III in surrendering his nation to the power of the papacy. While John’s motives for this action were clearly mixed and some historians see the move as a brilliant tactical maneuver, the fact remains that England had become a papal fiefdom and was subsequently plunged into civil war. As a result, John’s reputation had suffered for more than three centuries. While the reformation of John’s reputation was gradual and not simply a product of Cromwell’s Protestant propaganda campaign or Bale’s skills as a polemical 1 playwright, it does reflect a fundamental refocusing and reinterpretation of English history from the new perspective occasioned by Henry VIII’s break with Rome and the parallel emergence of a uniquely Protestant view of God, King, and Country.