TRB TCRP RRD: Germany's Track-Sharing Experience: Mixed Use of Rail Corridors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2.2 Pointwork Configurations in the Following Paragraphs Some of the More Maintenance Is Straightforward

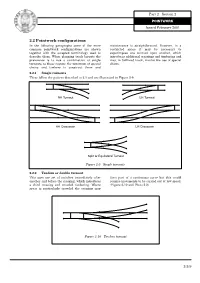

Part 2 Section 2 POINTWORK Issued February 2001 2.2 Pointwork configurations In the following paragraphs some of the more maintenance is straightforward. However, in a common pointwork configurations are shown restricted space it may be necessary to together with the accepted terminology used to superimpose one turnout upon another, which describe them. When planning track layouts the introduces additional crossings and timbering and preference is to use a combination of single may, in bullhead track, involve the use of special turnouts as these require the minimum of special chairs. chairs and timbers to construct them and 2.2.1 Single turnouts These follow the pattern described in 2.1 and are illustrated in Figure 2-9. RH Turnout LH Turnout RH Crossover LH Crossover Split or Equilateral Turnout Figure 2-9 Single turnouts 2.2.2 Tandem or double turnout This uses one set of switches immediately after form part of a continuous curve but this would another and before the crossing, which introduces require movements to be carried out at low speed. a third crossing and crowded timbering. Where (Figure 2-10 and Photo 2.2) space is particularly crowded the crossing may Figure 2-10 Tandem turnout 2-2-9 2.2.3 Three-throw turnout Photo 2.2 A double tandem turnout leading off from a double There is a nomenclature problem here slip at Stowmarket Goods Yard. as the 3-throw yields the same outcome (NRM Windwood Collection GE1005) as the double turnout. It uses a left hand and a right hand set of switches that are superimposed to divide three ways together in symmetrical form. -

Making Rail Accessible: Helping Older and Disabled Customers

TfL Rail Making rail accessible: Helping older and disabled customers May 2016 MAYOR OF LONDON Contents Our commitment to you page 3 Commitments page 5 Assistance for passengers page 6 Alternative accessible transport page 9 Passenger information page 10 Fares and tickets page 12 At the station page 16 On the train page 17 Making connections page 19 Accessible onward transport page 20 Disruption to facilities and services page 21 Contact us page 23 Station accessibility information page 24 Contact information back page 2 Our commitment to you TfL Rail is managed by Transport for London (TfL) and operated by MTR Crossrail. We operate rail services between Liverpool Street and Shenfield. At TfL Rail, we are committed to providing you with a safe, reliable and friendly service. We want to make sure that you can use our services safely and in comfort. 3 Our commitment to you (continued) We recognise that our passengers may have different requirements when they travel with us and we are committed to making your journey as easy as possible. This applies not only to wheelchair users, but also: • Passengers with visual or auditory impairment or learning disabilities • Passengers whose mobility is impaired through arthritis or other temporary or long term conditions • Older people • Passengers accompanying disabled children in pushchairs • Disabled passengers requiring assistance with luggage We welcome your feedback on the service we provide and any suggestions you may have for improvements. Our contact details are shown on the back page of this -

Metro Rail Design Criteria Section 10 Operations

METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 OPERATIONS METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 10.1 INTRODUCTION 1 10.2 DEFINITIONS 1 10.3 OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE PLAN 5 Metro Baseline 10- i Re-baseline: 06/15/10 METRO RAIL DESIGN CRITERIA SECTION 10 / OPERATIONS OPERATIONS 10.1 INTRODUCTION Transit Operations include such activities as scheduling, crew rostering, running and supervision of revenue trains and vehicles, fare collection, system security and system maintenance. This section describes the basic system wide operating and maintenance philosophies and methodologies set forth for the Metro Rail Projects, which shall be used by designer in preparation of an Operations and Maintenance Plan. An initial Operations and Maintenance Plan (OMP) is developed during the environmental phase and is based on ridership forecasts produced during this early planning phase of a project. From this initial Operations and Maintenance plan, headways are established that are to be evaluated by a rail operations simulation upon which design and operating headways can be established to confirm operational goals for light and heavy rail systems. The Operations and Maintenance Plan shall be developed in order to design effective, efficient and responsive transit system. The operations criteria and requirements established herein represent Metro’s Rail Operating Requirements / Criteria applicable to all rail projects and form the basis for the project-specific operational design decisions. They shall be utilized by designer during preparation of Operations and Maintenance Plan. Any proposed deviation to Design Criteria cited herein shall be approved by Metro, as represented by the Change Control Board, consisting of management responsible for project construction, engineering and management, as well as daily rail operations, planning, systems and vehicle maintenance with appropriate technical expertise and understanding. -

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

Bus and Shared-Ride Taxi Use in Two Small Urban Areas

Bus and Shared-Ride Taxi Use in Two Small Urban Areas David P. Middendorf, Peat, Marwick, Mitchell and Company Kenneth W. Heathington, University of Tennessee The demand for publicly owned fixed-route. fixed-schedule bus service are used for work and business-related trips to and was compared with tho demand for privately owned shared-ride taxi ser within CBDs and for short social, shopping, medical, vice in Davenport. Iowa, and Hicksville, New York, through on-board and personal business trips. surveys end cab company dispatch records and driver logs. The bus and In many small cities and in many suburbs of large slmrcd·ride taxi systems in Davenport com11eted for the off.peak-period travel market. During off-peak hours, the taxis tended to attract social· metropol.il;e:H!:i, l.lus~s nd taxicabs operate within tlie recreation, medical, and per onal business trips between widely scattered same jlu·isclictions and may compete for the same public origins and destinations, while the buses tended 10 attract shopping and transportation market. Two examples of small commu personal business trips to the CBD. The shared-ride taxi system in Hicks· nities in which buses and ta.xis coexist are Davenport, ville, in addition to providing many-to·many service, competed with the Iowa, and Hicksville, New York. The markets, eco counlywide bus system as a feeder system to the Long Island commuter nomic characteristics, organization, management, and railroad network. In each study area, the markets of each mode of public operation of the taxicab systems sel'Ving these commu transportation were similar. -

Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen 2021

Abfuhrkalender 2021 AbfallWirtschaftsBetrieb für Privathaushalte Eggenstein-Leopoldshafen Landkreis Karlsruhe Dez. 2020 Januar Februar März April Mai Juni 1 Di 1 Fr Neujahr 1 Mo 1 Mo 1 Do 1 Sa Tag der Arbeit 1 Di 2 Mi 2 Sa 2 Di 2 Di 2 Fr Karfreitag 2 So 2 Mi + + 3 Do 3 So 3 Mi 3 Mi 3 Sa 3 Mo 3 Do Fronleichnam + 4 Fr 4 Mo 4 Do 4 Do 4 So 4 Di 4 Fr 5 Sa 5 Di 5 Fr 5 Fr 5 Mo Ostermontag 5 Mi 5 Sa + 6 So 6 Mi Heilige drei Könige 6 Sa 6 Sa 6 Di 6 Do 6 So 7 Mo 7 Do 7 So 7 So 7 Mi 7 Fr 7 Mo 8 Di 8 Fr 8 Mo 8 Mo 8 Do 8 Sa 8 Di + + + 9 Mi 9 Sa 9 Di 9 Di 9 Fr 9 So 9 Mi + wö + 10 Do 10 So 10 Mi 10 Mi 10 Sa 10 Mo 10 Do + + 11 Fr 11 Mo 11 Do 11 Do 11 So 11 Di 11 Fr + 12 Sa 12 Di 12 Fr 12 Fr 12 Mo 12 Mi 12 Sa 13 So 13 Mi 13 Sa 13 Sa 13 Di 13 Do Christi Himmelfahrt 13 So + wö + 14 Mo 14 Do 14 So 14 So 14 Mi 14 Fr 14 Mo + 15 Di 15 Fr 15 Mo 15 Mo 15 Do 15 Sa 15 Di 16 Mi 16 Sa 16 Di 16 Di 16 Fr 16 So 16 Mi + + + 17 Do 17 So 17 Mi 17 Mi 17 Sa 17 Mo 17 Do 18 Fr 18 Mo 18 Do 18 Do 18 So 18 Di 18 Fr 19 Sa 19 Di 19 Fr 19 Fr 19 Mo 19 Mi 19 Sa + 20 So 20 Mi 20 Sa 20 Sa 20 Di 20 Do 20 So + 21 Mo 21 Do 21 So 21 So 21 Mi 21 Fr 21 Mo + 22 Di 22 Fr 22 Mo 22 Mo 22 Do 22 Sa 22 Di + + 23 Mi 23 Sa 23 Di 23 Di 23 Fr 23 So 23 Mi wö + 24 Do 24 So 24 Mi 24 Mi 24 Sa 24 Mo Pfingstmontag 24 Do + + 25 Fr 1. -

The Climate Impacts of High-Speed Rail and Air Transportation: a Global Comparative Analysis

The Climate Impacts of High-Speed Rail and Air Transportation: A Global Comparative Analysis by Regina Ruby Lee Clewlow B.S. Computer Science, Cornell University (2001) M.Eng. Civil and Environmental Engineering, Cornell University (2002) Submitted to the Engineering Systems Division in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2012 © Regina R. L. Clewlow All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author ............................................................................................................................ Engineering Systems Division August 17, 2012 Certified by ........................................................................................................................................ Joseph M. Sussman JR East Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Engineering Systems Thesis Supervisor Certified by ........................................................................................................................................ Hamsa Balakrishnan Assistant Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Certified by ........................................................................................................................................ Mort D. Webster Assistant Professor of -

Surface Access Integrated Ticketing Report May 2018 1

SURFACE ACCESS INTEGRATED TICKETING REPORT MAY 2018 1. Contents 1. Executive Summary 3 1.1. Introduction 3 1.2. Methodology 3 1.3. Current Practice 4 1.4. Appetite and Desire 5 1.5. Barriers 5 1.6. Conclusions 6 2. Introduction 7 3. Methodology 8 4. Current Practice 9 4.1. Current Practice within the Aviation Sector in the UK 11 4.2. Experience from Other Modes in the UK 15 4.3. International Comparisons 20 5. Appetite and Desire 25 5.1. Industry Appetite Findings 25 5.2. Passenger Appetite Findings 26 5.3. Passenger Appetite Summary 30 6. Barriers 31 6.1. Commercial 32 6.2. Technological 33 6.3. Regulatory 34 6.4. Awareness 35 6.5. Cultural/Behavioural 36 7. Conclusions 37 8. Appendix 1 – About the Authors 39 9. Appendix 2 – Bibliography 40 10. Appendix 3 – Distribution & Integration Methods 43 PAGE 2 1. Executive Summary 1.1. Introduction This report examines air-to-surface access integrated ticketing in support of one of the Department for Transport’s (DfT) six policy objectives in the proposed new avia- tion strategy – “Helping the aviation industry work for its customers”. Integrated Ticketing is defined as the incorporation of one ticket that includes sur- face access to/from an airport and the airplane ticket itself using one transaction. Integrated ticketing may consider surface access journeys both to the origin airport and from the destination airport. We recognise that some of the methods of inte- grated ticketing might not be truly integrated (such as selling rail or coach tickets on board the flight), but such examples were included in the report to reflect that these exist and that the customer experience in purchasing is relatively seamless. -

Comparison Between Bus Rapid Transit and Light-Rail Transit Systems: a Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach

Urban Transport XXIII 143 COMPARISON BETWEEN BUS RAPID TRANSIT AND LIGHT-RAIL TRANSIT SYSTEMS: A MULTI-CRITERIA DECISION ANALYSIS APPROACH MARÍA EUGENIA LÓPEZ LAMBAS1, NADIA GIUFFRIDA2, MATTEO IGNACCOLO2 & GIUSEPPE INTURRI2 1TRANSyT, Transport Research Centre, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, Spain 2Department of Civil Engineering and Architecture (DICAR), University of Catania, Italy ABSTRACT The construction choice between two different transport systems in urban areas, as in the case of Light-Rail Transit (LRT) and Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) solutions, is often performed on the basis of cost-benefit analysis and geometrical constraints due to the available space for the infrastructure. Classical economic analysis techniques are often unable to take into account some of the non-monetary parameters which have a huge impact on the final result of the choice, since they often include social acceptance and sustainability aspects. The application of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) techniques can aid decision makers in the selection process, with the possibility to compare non-homogeneous criteria, both qualitative and quantitative, and allowing the generation of an objective ranking of the different alternatives. The coupling of MCDA and Geographic Information System (GIS) environments also permits an easier and faster analysis of spatial parameters, and a clearer representation of indicator comparisons. Based on these assumptions, a LRT and BRT system will be analysed according to their own transportation, economic, social and environmental impacts as a hypothetical exercise; moreover, through the use of MCDA techniques a global score for both systems will be determined, in order to allow for a fully comprehensive comparison. Keywords: BHLS, urban transport, transit systems, TOPSIS. -

Wochenzeitung Der Stadt Baunatal

Wochenzeitung derStadt Baunatal Jahrgang 56 Mittwoch, 16.September2020Nr. 38 Immobilienmakler Einladungzur Bürgerversammlung BAUNATAL Donnerstag, 17.September2020, 18.00Uhr, Stadthalle Baunatal ZurBürgerversammlunggemäß §8aGemeindeordnungmit dem Schwerpunktthema Bewertung ·Beratung ·Verkauf 34225 Baunatal -Kirchbaunaer Str.5 DieZukunftder SportstadtBaunatal www.die5immoagentur.de 0561.503346-25 lade ich für Donnerstag,den 17.09.2020 um 18.00Uhr in dieStadthalle Baunatal herzlichein. Ichgebealleninteressierten Mitbürgerinnenund Mitbürgerndie Möglich- keit zurTeilnahme. Zu Beginn wird Bürgermeisterin Engler einenÜberblicküberdie derzeiti- ge Situationder städtischenSporteinrichtungenund dessen Nutzungge- ben. Im Anschluss werden dieGastreferentenProf. Dr.Hottenrot und Prof.Dr. Obingervon derDeutschenBerufsakademiefür Sportund Ge- sundheit, dasKonzept desSportentwicklungsplan derStadt Baunatal vor- Anzeigen stellenund hierzuIhreFragenbeantworten. Mandatsträgerder im Stadtparlamentvertretenden Parteien alsauchVer- treter desMagistratesstehenIhnen im Anschluss zu diesemund anderen Themen alsGesprächspartnerund zuroffenenDiskussion zurVerfügung. AufGrund derCorona-Pandemie undder einhergehenden Sicherheits- vorschriftenbitteich Sieeinen Mund-und Nasenschutz zu derVeranstal- tung mitzubringen.Die Anzahl derSitzplätzeinder Stadthalle wirdauf 90 begrenzt. BeiBedarfwerden weitere Steh-und SitzplätzeimFoyer der Stadthalle unterBeachtung derHygienevorschriftenhergerichtet. Ichbitte Siehierfür um Verständnis. HenryRichter Stadtverordnetenvorsteher -

LP NVK Anhang (PDF, 7.39

Landschaftsplan 2030 Nachbarschaftsverband Karlsruhe 30.11.2019 ANHANG HHP HAGE+HOPPENSTEDT PARTNER INHALT 1 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.1 – DER RAUM ........................................................... 1 1.1 Schutzgebiete ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Naturschutzgebiete ................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Landschaftsschutzgebiete ........................................................................ 2 1.1.3 Wasserschutzgebiete .................................................................................. 4 1.1.4 Überschwemmungsgebiete ...................................................................... 5 1.1.5 Waldschutzgebiete ...................................................................................... 5 1.1.6 Naturdenkmale – Einzelgebilde ................................................................ 6 1.1.7 Flächenhaftes Naturdenkmal .................................................................... 10 1.1.8 Schutzgebiete NATURA 2000 .................................................................... 11 1.1.8.1 FFH – Gebiete 11 1.1.8.2 Vogelschutzgebiete (SPA-Gebiete) 12 2 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.2 – GESUNDHEIT UND WOHLBEFINDEN DER MENSCHEN ..................... 13 3 ANHANG ZU KAP. 2.4 - LANDSCHAFT ..................................................... 16 3.1 Landschaftsbeurteilung ............................................................................................... -

The Myth of the Standard Gauge

The Myth of the Standard Guage: Rail Guage Choice in Australia, 1850-1901 Author Mills, John Ayres Published 2007 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/426 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366364 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au THE MYTH OF THE STANDARD GAUGE: RAIL GAUGE CHOICE IN AUSTRALIA, 1850 – 1901 JOHN AYRES MILLS B.A.(Syd.), M.Prof.Econ. (U.Qld.) DEPARTMENT OF ACCOUNTING, FINANCE & ECONOMICS GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL GRIFFITH UNIVERSITY Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2006 ii ABSTRACT This thesis describes the rail gauge decision-making processes of the Australian colonies in the period 1850 – 1901. Federation in 1901 delivered a national system of railways to Australia but not a national railway system. Thus the so-called “standard” gauge of 4ft. 8½in. had not become the standard in Australia at Federation in 1901, and has still not. It was found that previous studies did not examine cause and effect in the making of rail gauge choices. This study has done so, and found that rail gauge choice decisions in the period 1850 to 1901 were not merely one-off events. Rather, those choices were part of a search over fifty years by government representatives seeking colonial identity/autonomy and/or platforms for election/re-election. Consistent with this interpretation of the history of rail gauge choice in the Australian colonies, no case was found where rail gauge choice was a function of the disciplined search for the best value-for-money option.