The Last Flight of Wellington Mp.630]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military Aircraft Crash Sites in South-West Wales

MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH-WEST WALES Aircraft crashed on Borth beach, shown on RAF aerial photograph 1940 Prepared by Dyfed Archaeological Trust For Cadw DYFED ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST RHIF YR ADRODDIAD / REPORT NO. 2012/5 RHIF Y PROSIECT / PROJECT RECORD NO. 105344 DAT 115C Mawrth 2013 March 2013 MILITARY AIRCRAFT CRASH SITES IN SOUTH- WEST WALES Gan / By Felicity Sage, Marion Page & Alice Pyper Paratowyd yr adroddiad yma at ddefnydd y cwsmer yn unig. Ni dderbynnir cyfrifoldeb gan Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf am ei ddefnyddio gan unrhyw berson na phersonau eraill a fydd yn ei ddarllen neu ddibynnu ar y gwybodaeth y mae’n ei gynnwys The report has been prepared for the specific use of the client. Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited can accept no responsibility for its use by any other person or persons who may read it or rely on the information it contains. Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Dyfed Cyf Dyfed Archaeological Trust Limited Neuadd y Sir, Stryd Caerfyrddin, Llandeilo, Sir The Shire Hall, Carmarthen Street, Llandeilo, Gaerfyrddin SA19 6AF Carmarthenshire SA19 6AF Ffon: Ymholiadau Cyffredinol 01558 823121 Tel: General Enquiries 01558 823121 Adran Rheoli Treftadaeth 01558 823131 Heritage Management Section 01558 823131 Ffacs: 01558 823133 Fax: 01558 823133 Ebost: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Gwefan: www.archaeolegdyfed.org.uk Website: www.dyfedarchaeology.org.uk Cwmni cyfyngedig (1198990) ynghyd ag elusen gofrestredig (504616) yw’r Ymddiriedolaeth. The Trust is both a Limited Company (No. 1198990) and a Registered Charity (No. 504616) CADEIRYDD CHAIRMAN: Prof. B C Burnham. CYFARWYDDWR DIRECTOR: K MURPHY BA MIFA SUMMARY Discussions amongst the 20th century military structures working group identified a lack of information on military aircraft crash sites in Wales, and various threats had been identified to what is a vulnerable and significant body of evidence which affect all parts of Wales. -

Brighton City Airport (Shoreham) Heritage Assessment March 2016

Brighton City Airport (Shoreham) Heritage Assessment March 2016 Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Setting, character and designations 3 3. The planning context 5 4. The history of the airfield to 1918 7 5. The end of the First World War to the outbreak of the Second 10 6. The Second World War 13 7. Post-war history 18 8. The dome trainer and its setting 20 9. The airfield as the setting for historical landmarks 24 10 Significance 26 11. Impacts and their effects 33 12. Summary and conclusions 40 13. References 42 Figures 1. The proposed development 2. The setting of the airfield 3. The view northwards from the airfield to Lancing College 4. Old Shoreham Bridge and the Church of St Nicolas 5. The view north eastwards across the airfield to Old Shoreham 6. Principal features of the airfield and photograph viewpoints 7. The terminal building, municipal hangar and the south edge of the airfield 8. The tidal wall looking north 9. The railway bridge 10. The dome trainer 11. The north edge and north hangar 12. The airfield 1911-1918 13. The 1911 proposals 14. The airfield in the 1920s and 1930s 15. The municipal airport proposal 16. Air photograph of 1936 17. Airfield defences 1940-41 18. Air photograph, November 1941 19. Map of pipe mines 20. Air photograph, April 1946 21. Air Ministry drawing, 1954 22. The airfield in 1967 23. Post-war development of the south edge of the airfield 24. Dome trainer construction and use 25. Langham dome trainer interior 26. Langham dome trainer exterior 27. -

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:R 5 1954 253

KUNGL ÖRLOGSMANNA SÄLLSKAPET N:r 5 1954 253 Kring några nyförvärv i Kungl. Orlogs- 111annasällskapets bibliotek Av Kommendörkapten GEORG HAFSTRöM. Bland äldre böcker, som_ under de senare åren tillförts Sällskapets bibliotek befinner sig fyra handskrivna volym_er, mottagna såsom gåva från ett sterbhus. Två av dessa här• stammar från slutet av 1700-talet och två från förra hälften av 1800-talet. De är skrivna av tvenne sjöofficerare, resp. far och son, nämligen fänriken vid amiralitetet Michael J a rislaf von Bord-. och premiärlöjtnanten vid Kungl. Maj :ts flotta J o han August von Borclc Som de inte sakna sitt in tresse vid studiet av förhållandena inom flottan under an förda tid utan fastmera bidrager att i sin mån berika vår kännedom om vissa delar av tjänsten och livet inom sjövap• net, må några ord om desamma här vara på sin plats. Först några orienterande data om herrarna von Borclc De tillhör de en gammal pommersk adelssläkt, som under svensktiden såg flera av sina söner ägna sig åt krigaryrket. Ej mindre än 6 von Borekar tillhörde sålunda armen un der Karl XII :s dagat·, samtliga dragonofficerare. Och un der m itten och senare delen av 1700-talet var 3 medlemmar av ätten officerare vid det i Siralsund garnisonerade Drott ningens livregemente. Förmodligen son till den äldste av dessa sistnämnda föd• des Michael Jarislaf von Borck 1758. Han antogs 1786 till arklintästare vid amiralitetet och utnämndes 1790 till fän• rik, P å hösten 1794 begärde han 3 års permission »för att un der sitt nuvarande vistande i England vinna all möjlig för• ~<ovr an i metiern». -

Sir Frank Cooper on Air Force Policy in the 1950S & 1960S

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society Copyright © Royal Air Force Historical Society, 1993 All rights reserved. 1 Copyright © 1993 by Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 1993 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. Printed by Hastings Printing Company Limited Royal Air Force Historical Society 2 THE PROCEEDINGS OFTHE ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY Issue No 11 President: Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Committee Chairman: Air Marshal Sir Frederick B Sowrey KCB CBE AFC General Secretary: Group Captain J C Ainsworth CEng MRAeS Membership Secretary: Commander P O Montgomery VRD RNR Treasurer: D Goch Esq FCCA Programme Air Vice-Marshal G P Black CB OBE AFC Sub-Committee: Air Vice-Marshal F D G Clark CBE BA Air Commodore J G Greenhill FBIM T C G James CMG MA *Group Captain I Madelin Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA Group Captain A R Thompson MBE MPhil BA FBIM MIPM Members: A S Bennell Esq MA BLitt *Dr M A Fopp MA PhD FMA FBIM A E Richardson *Group Captain N E Taylor BSc D H Wood Comp RAeS * Ex-officio The General Secretary Regrettably our General Secretary of five years standing, Mr B R Jutsum, has found it necessary to resign from the post and the committee. -

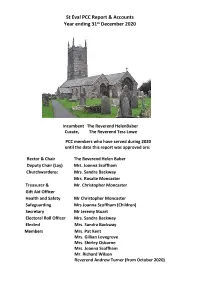

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year Ending 31St December 2020

St Eval PCC Report & Accounts Year ending 31st December 2020 Incumbent The Reverend HelenBaber Curate, The Reverend Tess Lowe PCC members who have served during 2020 until the date this report was approved are: Rector & Chair The Reverend Helen Baber Deputy Chair (Lay) Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Churchwardens: Mrs. Sandra Backway Mrs. Rosalie Moncaster Treasurer & Mr. Christopher Moncaster Gift Aid Officer Health and Safety Mr Christopher Moncaster Safeguarding Mrs Joanna Scoffham (Children) Secretary Mr Jeremy Stuart Electoral Roll Officer Mrs. Sandra Backway Elected Mrs. Sandra Backway Members Mrs. Pat Kent Mrs. Gillian Lovegrove Mrs. Shirley Osborne Mrs. Joanna Scoffham Mr. Richard Wilson Reverend Andrew Turner (from October 2020) The method of appointment of PCC members is set out in the Church Representation Rules. All church Attendees are encouraged to register on the Electoral Roll and stand for election to the PCC. The PCC met twice during the year. St. Eval PCC has the responsibility of co-operating with the incumbent in promoting the whole mission of the church, pastoral, evangelistic, social and ecumenical in the ecclesiastical parish. It also has maintenance responsibilities for the church, churchyard, church room, toilet block and grounds. The Parochial Church Council (PCC) is a charity excepted from registration with the Charity Commission. The church is part of the Diocese of Truro within the Church of England and is one of the four churches in the Lann Pydar Benefice. The other Parishes are St. Columb Major, St. Ervan and St. Mawgan-in-Pydar. The Parish Office, which is shared with the other 3 churches within the benefice, has now been relocated to the Rectory in St Columb Major. -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

Seeschlachten Im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung)

Seeschlachten im Atlantik (Zusammenfassung) U-Boot-Krieg (aus Wikipedia) 07_48/U 995 vom Typ VII C/41, der meistgebauten U-Boot-Klasse im Zweiten Weltkrieg Als U-Boot-Krieg (auch "Unterseebootkrieg") werden Kampfhandlungen zur See bezeichnet, bei denen U-Boote eingesetzt werden, um feindliche Kriegs- und Frachtschiffe zu versenken. Die Bezeichnung "uneingeschränkter U-Boot-Krieg" wird verwendet, wenn Schiffe ohne vorherige Warnung angegriffen werden. Der Einsatz von U-Booten wandelte sich im Laufe der Zeit vom taktischen Blockadebrecher zum strategischen Blockademittel im Rahmen eines Handelskrieges. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg änderte sich die grundsätzliche Einsatzdoktrin durch die Entwicklung von Raketen tragenden Atom- U-Booten, die als Träger von Kernwaffen eine permanente Bedrohung über den maritimen Bereich hinaus darstellen. Im Gegensatz zum Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg fand hier keine völkerrechtliche Weiterentwicklung zum Einsatz von U-Booten statt. Der Begriff wird besonders auf den Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg bezogen. Hierbei sind auch völkerrechtliche Rahmenbedingungen von Bedeutung. Anfänge Während des Amerikanischen Bürgerkrieges wurden 1864 mehrere handgetriebene U-Boote gebaut. Am 17. Februar 1864 versenkte die C.S.S. H. L. Hunley durch eine Sprengladung das Kriegsschiff USS Housatonic der Nordstaaten. Es gab 5 Tote auf dem versenkten Schiff. Die Hunley gilt somit als erstes U-Boot der Welt, das ein anderes Schiff zerstört hat. Das U-Boot wurde allerdings bei dem Angriff auf die Housatonic durch die Detonation schwer beschädigt und sank, wobei auch seine achtköpfige Besatzung getötet wurde. Auftrag der Hunley war die Brechung der Blockade des Südstaatenhafens Charleston durch die Nordstaaten. Erster Weltkrieg Die technische Entwicklung der U-Boote bis zum Beginn des Ersten Weltkrieges beschreibt ein Boot, das durch Dampf-, Benzin-, Diesel- oder Petroleummaschinen über Wasser und durch batteriegetriebene Elektromotoren unter Wasser angetrieben wurde. -

Vickers Armstrong Wellington.Pdf

FLIGHT, July 6. 1939. a Manoeuvrability is an outstanding quality of the Wellington. CEODETICS on the GRAND SCALE A Detailed Description of the Vickers-Armstrongs Wellington I : Exceptional Range and Large Bomb Capacity : Ingenious Structural Features (Illustrated mainly with "Flight" Photographs and Sketches) T is extremely unlikely that any foreign air force in place of the Pegasus XVIIIs); it has provision for five possesses bombers with as long a range as that attain turreted machine-guns; it is quite exceptionally roomy, I able by the Vickers-Armstrongs Wellington I (Type and it is amazingly agile in the air. 290), which forms the equipment of a number of The Bristol Pegasus XVIII engines fitted as standard in squadrons of the Royal Air Force and of which it is now permissible to dis close structural details. The Wellington's capa city for carrying heavy loads over great distances may be directly attributed to the Vickers geodetic system of construction, which proved its worth in the single-engined Welles- ley used" as standard equipment in a number of overseas squadrons of the R.A.F. But the qualities of the Wellington are not limited to load-carrying. It has a top speed of 265 m.p.h. (or consider ably more when fitted with Rolls-Royce Merlin or Bristol Hercules engines The Wellington, with its ex tremely long range, has comprehensive tankage ar rangements. The tanks (riveted by the De Bergue system) taper in conformity with the wing. FLIGHT, July 6, 1939. The rear section of the fuselage, looking toward the tail turret, with the chute for the reconnaissance flaref protuding on ihe left amidships. -

Coastal Command in the Second World War

AIR POWER REVIEW VOL 21 NO 1 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR By Professor John Buckley Biography: John Buckley is Professor of Military History at the University of Wolverhampton, UK. His books include The RAF and Trade Defence 1919-1945 (1995), Air Power in the Age of Total War (1999) and Monty’s Men: The British Army 1944-5 (2013). His history of the RAF (co-authored with Paul Beaver) will be published by Oxford University Press in 2018. Abstract: From 1939 to 1945 RAF Coastal Command played a crucial role in maintaining Britain’s maritime communications, thus securing the United Kingdom’s ability to wage war against the Axis powers in Europe. Its primary role was in confronting the German U-boat menace, particularly in the 1940-41 period when Britain came closest to losing the Battle of the Atlantic and with it the war. The importance of air power in the war against the U-boat was amply demonstrated when the closing of the Mid-Atlantic Air Gap in 1943 by Coastal Command aircraft effectively brought victory in the Atlantic campaign. Coastal Command also played a vital role in combating the German surface navy and, in the later stages of the war, in attacking Germany’s maritime links with Scandinavia. Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors concerned, not necessarily the MOD. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form without prior permission in writing from the Editor. 178 COASTAL COMMAND IN THE SECOND WORLD WAR introduction n March 2004, almost sixty years after the end of the Second World War, RAF ICoastal Command finally received its first national monument which was unveiled at Westminster Abbey as a tribute to the many casualties endured by the Command during the War. -

Bb16 Instruction

Belcher Belcher Bits BB-16: Bits Liberator GRV Dumbo Radome / Leigh Light 1/48 33 Norway Spruce Street, Stittsville, ON, Canada K2S 1P3 Phone: (613) 836-6575, e-mail: [email protected] Intended kit: Revell Monogram B-24D rine. The first installation The Coastal Command use of the long range B-24 for anti-submarine replaced the dustbin work was the beginning of the end of the U-Boat menace in the North Atlantic; retractable lower turret on it meant there was less opportunity for submarines to surface away from con- the Wellington with a voys to recharge batteries and receive radio directions. The B-24 had the range similar mount for the Leigh for the work required as well as the capacity for the load in addition to the radar Light. A later development fit, and the speed necessary for the attack. Earlier Coastal Command aircraft housed the light in a such as the Consolidated Canso (PBY) used Yagi antenna and underslung streamlined pod slung weapons which slowed the aircraft down (and they were never speedy to start under the wing. This large with) so that a depth charge attack on a surfaced submarine often turned into a pod added considerably to shooting match. the drag of the aircraft but The B-24D (or Liberator GR V in RAF service) were delivered to the the B-24 had the neces- RCAF with the ASV Mk III centimetric radar fitted in either a retractable sary power and generating radome replacing the belly turret, or the Dumbo radome below the nose green- capacity to operate the house. -

Three Rivers Cockle Fishery

Welsh Government Marine and Fisheries CORONAVIRUS (COVID-19) ADVICE Please check the Welsh Government website regularly (or locally posted Public Notices) for any changes to arrangements following Government advice. Link: https://gov.wales/three- rivers-cockle-fishery General advice and the current Welsh Government position can be found on the Welsh Government website. Link: https://gov.wales/coronavirus You can also check current Government guidelines and advice on the Public Health Wales website. Link: https://phw.nhs.wales/topics/latest-information-on-novel- coronavirus-covid-19/ SECTION A THIS PERMIT entitles the Permit Holder to fish for, take or remove cockles from beds notified as OPEN within the Three Rivers Estuary Cockle fishery. This Permit is issued under the authority of the Minister for Environment, Energy and Rural Affairs one of the Welsh Ministers, for the purposes of Byelaw 47 of the former South Wales Sea Fisheries Committee (“SWSFC”). The Byelaws of the former SWSFC now have effect as if made in a statutory instrument by the Welsh Ministers, by virtue of Article 13(1) of, and Schedule 3 to, the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009 (Commencement No.1, Consequential, Transitional and Savings Provisions) (England and Wales) Order 2010 (S.I. 2010/630 (c.42)). This Permit entitles you to fish for, take or remove cockles, subject to the conditions set out below, from any cockle bed within the “Three Rivers Estuary area” (defined below) which is, at the relevant time, notified as open to cockle fishing activities, during 2021. Please regularly check the website, locally posted notices and social media for updates regarding which beds (if any) are open. -

The Connection

The Connection ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Copyright 2011: Royal Air Force Historical Society First published in the UK in 2011 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISBN 978-0-,010120-2-1 Printed by 3indrush 4roup 3indrush House Avenue Two Station 5ane 3itney O72. 273 1 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 8arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 8ichael Beetham 4CB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air 8arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-8arshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman 4roup Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary 4roup Captain K J Dearman 8embership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol A8RAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA 8embers Air Commodore 4 R Pitchfork 8BE BA FRAes 3ing Commander C Cummings *J S Cox Esq BA 8A *AV8 P Dye OBE BSc(Eng) CEng AC4I 8RAeS *4roup Captain A J Byford 8A 8A RAF *3ing Commander C Hunter 88DS RAF Editor A Publications 3ing Commander C 4 Jefford 8BE BA 8anager *Ex Officio 2 CONTENTS THE BE4INNIN4 B THE 3HITE FA8I5C by Sir 4eorge 10 3hite BEFORE AND DURIN4 THE FIRST 3OR5D 3AR by Prof 1D Duncan 4reenman THE BRISTO5 F5CIN4 SCHOO5S by Bill 8organ 2, BRISTO5ES