Reflections from Bob Moses the Algebra Project, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Algebra Project Newsletter

December 15, 2020 NEWSLETTER Math Literacy | Is the Key | to 21st Century Citizenship! A student’s math Student voices his math literacy journey: Jevonnie literacy journey: I struggled through middle school. I barely made it to high school. The Jevonnie, p. 1 summer between 8th and 9th grade all athletes were required to be involved with the Young People’s Project Jevonnie, a high school senior (YPP) and the Algebra Project. I was really in Broward County, FL, shares not optimistic because it was doing math in the summer and all I wanted to do was his math literacy journey. work out and play football. But it was a totally different experience than what I Bob Moses & Henry envisioned it to be. The Algebra Project Hipps’ Fireside classroom when we started school was the Chat, link: p same. I was like, “oh, my gosh! I have math at 7:30 in the morning, every day.” Then I went and I was like… “wow this doesn’t feel The Algebra Project like a math class.” For the majority of the class you are not sitting down. in Broward County You are walking around, collaborating, talking with your friends, your peers, doing work with them. Ms. Caicedo is breaking things down. We Public Schools - would be so intrigued and involved in the lesson.… video highlights, p.2 As a YPP Math Literacy Worker (MLW) I got to see things outside of what my mind was always fixed on, which was sports. The kids came in Office of Academics: https:// and we started teaching them and I got to see the ‘mini-me’s’ – I got to www.browardschools.com/ see how I was in them. -

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in Mccomb, Mississippi, 1928-1964

“A Tremor in the Middle of the Iceberg”: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Local Voting Rights Activism in McComb, Mississippi, 1928-1964 Alec Ramsay-Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 1, 2016 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For Dana Lynn Ramsay, I would not be here without your love and wisdom, And I miss you more every day. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... ii Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter One: McComb and the Beginnings of Voter Registration .......................... 10 Chapter Two: SNCC and the 1961 McComb Voter Registration Drive .................. 45 Chapter Three: The Aftermath of the McComb Registration Drive ........................ 78 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 102 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 119 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have done this without my twin sister Hunter Ramsay-Smith, who has been a constant source of support and would listen to me rant for hours about documents I would find or things I would learn in the course of my research for the McComb registration -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

Waveland, Mississippi, November 1964: Death of Sncc, Birth of Radicalism

WAVELAND, MISSISSIPPI, NOVEMBER 1964: DEATH OF SNCC, BIRTH OF RADICALISM University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire: History Department History 489: Research Seminar Professor Robert Gough Professor Selika Ducksworth – Lawton, Cooperating Professor Matthew Pronley University of Wisconsin – Eau Claire May 2008 Abstract: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) was a nonviolent direct action organization that participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. After the Freedom Summer, where hundreds of northern volunteers came to participate in voter registration drives among rural blacks, SNCC underwent internal upheaval. The upheaval was centered on the future direction of SNCC. Several staff meetings occurred in the fall of 1964, none more important than the staff retreat in Waveland, Mississippi, in November. Thirty-seven position papers were written before the retreat in order to reflect upon the question of future direction of the organization; however, along with answers about the future direction, these papers also outlined and foreshadowed future trends in radical thought. Most specifically, these trends include race relations within SNCC, which resulted in the emergence of black self-consciousness and an exodus of hundreds of white activists from SNCC. ii Table of Contents: Abstract ii Historiography 1 Introduction to Civil Rights and SNCC 5 Waveland Retreat 16 Position Papers – Racial Tensions 18 Time after Waveland – SNCC’s New Identity 26 Conclusion 29 Bibliography 32 iii Historiography Research can both answer questions and create them. Initially I discovered SNCC though Taylor Branch’s epic volumes on the Civil Right Movements in the 1960s. Further reading revealed the role of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced Snick) in the Civil Right Movement and opened the doors into an effective and controversial organization. -

September 13, 2013 EIR Scoping Period Comment Commenter Date Received Letter

Valero Crude by Rail Project Public Comments received August 9 - September 13, 2013 EIR Scoping Period Comment Commenter Date Received Letter ............ .'.: ... '··.·.·.·.i·.....·.·"....·.··.... ..... >.; ....••.......• ::.;.;., •... '" ................ ..•. ••. ..• .•... "...•.. i •. .•·.i ......... ...... Al California Public Utlities Commission, Ken Chiang, P.E. Ulilities Engineer 28-Aug-13 A2 Linda Scourtis, Bay Area Conservation and Development Commission 3-Sep-13 A3 Caltans, Erik Aim, District Branch Chief, Local Oeve!opment~lntergovernmenta! Review 6-Sep-13 . .... .'. OiganizBtl()n~·.·.... •.•....• ••.••• ••.•. .•...•. .i/<'.' •..... '.>. ,... .... .......•••••.. '.........•.•.•............... ' ..... Bl INatural Resources Defense Council 13-Sep-13 .·/··· ••·.·.··;)·\·,.· .•. • •• ··.··.·r> ·•·••• ···.··i·/.·.·· ..y•............ ·C/;{··.·(·.···...••. L• .•.....•.. <.•., .•.....•..••.•••............ > •. C1 Grant Cooke 13-Aug-13 C2 Roger Straw 19-Aug-13 C3 Roger Straw 21-Aug-13 C4 Dennis Lewis 26-Aug-13 C5 Rick Slizeski 11-Sep-13 C6 Kathy Kerridge 12-Sep-13 C7 Roger Straw 12-Sep-13 C8 Clark Driggars 12-Sep-13 C9 Roger Straw J Mary Frances Kelly Poh 12-Sep-13 Cl0 Mary Frances Kelly Poh 13-Sep-13 Cl1 Milton Kalish 13-Sep-13 C12 Marilyn 8ardet 13-Sep-13 C13 Donald Dean 13-Sep-13 C14 Charles Davidson 13-Sep-13 C15 Lynne NUtter and Richard McAdam 13-Sep-13 C16 Ed Ruszel 13-Sep-13 C17 Judith S. Sullivan 13-Sep-13 STATE OF CALIFORNIA EDMUND G. BROWN JR .• Governor PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION 320 WEST 4TH STREET, SUITE 500 lOS ANGELES, CA 90013 (213) 576-7083 July 2, 2013 Charlie Knox City of Benicia 250 E. L Street Benicia, California 94510 Dear Mr. Knox: Re: SCH# 2013052074; Valero Crude Oil by Rail Project, Valero Benicia Refinery DMND The California Public Utilities Commission (Commission) has jurisdiction over the safety of highway-rail crossings (crossings) in California. -

The Struggle for Voting Rights in Mississippi ~ the Early Years

The Struggle for Voting Rights in Mississippi ~ the Early Years Excerpted from “History & Timeline” Mississippi — the Eye of the Storm It is a trueism of the era that as you travel from the north to the south the deeper grows the racism, the worse the poverty, and the more brutal the repression. In the geography of the Freedom Movement the South is divided into mental zones according to the virulence of bigotry and oppression: the “Border States” (Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, and the urban areas of Maryland); the “Mid South” (Virginia, the East Shore of Maryland, North Carolina, Florida, Tennessee, Arkansas, Texas); and the “Deep South” (South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana). And then there is Mississippi, in a class by itself — the absolute deepest pit of racism, violence, and poverty. During the post-Depression decades of the 1940s and 1950s, most of the South experiences enormous economic changes. “King Cotton” declines as agriculture diversifies and mechanizes. In 1920, almost a million southern Blacks work in agriculture, by 1960 that number has declined by 75% to around 250,000 — resulting in a huge migration off the land into the cities both North and South. By 1960, almost 60% of southern Blacks live in urban areas (compared to roughly 30% in 1930). But those economic changes come slowly, if at all, to Mississippi and the Black Belt areas of Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. In 1960, almost 70% of Mississippi Blacks still live in rural areas, and more than a third (twice the percentage in the rest of the South) work the land as sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and farm laborers. -

The 6Th Circuit Court and the Constitutional Right to a Foundational Level of Literacy

THE 6TH CIRCUIT COURT AND THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO A FOUNDATIONAL LEVEL OF LITERACY Throughout U.S. history the courts, Congress, local legislatures, and the executive branch of government have resisted the idea that public school students have a constitutional right to meaningful education. Our decades of work with the Algebra Project bring this into sharp focus. The lack of opportunity rooted inside the educational system, and with mathematics in particular, continues to lock generations of youth from full participation in democracy and the economy, basically making full citizenship impossible. Furthermore, the caste system created by this failure has broadened to include not just blacks, but people of color and people living in poverty. On April 24 of this year, the 6th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Cincinnati ruled that there is a Constitutional right to a “foundational level of literacy.” This opens a small window that raises the possibility to meaningfully turn around this long-standing disparity. This is an organizing opportunity – a time to make it clear to the many who will not know of this 6th Circuit ruling and what implementing it will mean to those being left out of equal educational opportunity. Now is the time to generate pressure. I have spent a lifetime both participating in and witnessing the critical connection between organized pressure directed at laws and lawmakers and achieving meaningful change. In the early 1960s, field secretaries of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) of whom I was one, organized a campaign aimed at gaining the right to vote—an insurgency really—which led to the federal Justice Department bringing suits against the states of Mississippi and Louisiana. -

HONORING CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT VETERANS “Write That I” Poems

HONORING CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT VETERANS “Write That I” Poems Poetry by Teachers in the 2018 NEH Summer Institute on the Civil Rights Movement: Grassroots Perspectives Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University, SNCC Legacy Project, and Teaching for Change July, 2018 Table of Contents ABOUT THE COLLECTION........................................................................................................................................ 1 AMELIA BOYNTON ................................................................................................................................................. 2 FOR AMZIE MOORE ............................................................................................................................................... 4 ANNE BRADEN ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ANNIE PEARL AVERY .............................................................................................................................................. 9 BAYARD RUSTIN .................................................................................................................................................. 11 BERNARD LAFAYETTE JR. ..................................................................................................................................... 14 SPROUTING REVOLUTION: BETITA MARTÍNEZ .................................................................................................... -

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project

I appeal to you to hlep us make the most of the historic opportunities before 20 July us. PLEASE SEND WHATEVER CONTRIBUTION YOU CAN AFFORD TODAY. 1960 Speed your gift now in the enclosed envelope. NO POSTAGE IS NECESSARY. In addition to your immediate contribution, I would also like to urge you to make an annual pledge to our organization. Also, have your church, club, or other or- ganization to do likewise. This will keep our work going on a substantial basis. The pledge card is enclosed-please return it todaywith your contribution. As you write your check think of a few of our heroic board members such as Daisy Bates, Fred Shuttlesworth, C. K. Steele, Ralph D. Abernathy, only to mention a few, and the heroic students of the South. If they can face jeering and hostile mobs and suffer brutal and nightmarish bombings to advance justice, how can you and I be less generous in our support? Yours for the cause of freedom, [signed] Martin Luther King Jr. Martin Luther King, Jr. President Attest: Ralph D. Abernathy Financial Secretary-Treasurer MLKAmh Enclosures: 2 P.S. If you receive more than one of these letters, then please pass it on to a friend. THLS. ERC-NHyF The Martin Luther King, Jr. Papers Project From Ella J. Baker 20 July 1960 Shortly before resigning as executive director, Baker recommends that Bob Moses be sent lo assist leaders 0fSCLCk Louisiana affiliate, the United Christian Movement.’ Moses, a high school math teacher, had come to know Baker while volunteering at I. Baker cited “the need for some extended rest” and upcoming cataract surgery as reasons for her I August resignation (Baker, Form letter to Friend, 31Jdy 1960).Robert Parris Moses (1935- ), ’ born in New York City, received a B.A. -

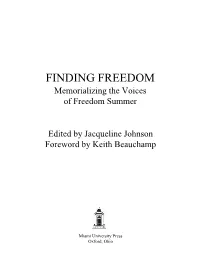

FINDING FREEDOM Memorializing the Voices of Freedom Summer

FINDING FREEDOM Memorializing the Voices of Freedom Summer Edited by Jacqueline Johnson Foreword by Keith Beauchamp Miami University Press Oxford, Ohio Ann Elizabeth Armstrong The Mississippi Summer Project ANN ELIZABETH ARMSTRONG THE MISSISSIPPI SUMMER PROJECT The Mississippi Summer Project of 1964 was a complex and creative campaign that took place at a crucial turning point in the civil rights movement. It was part of a multipronged initiative designed to engage the entire nation with the plight of African Americans in Mississippi and shift the spotlight on the violence and injustice there. “Freedom Summer,” as it would later be called,1 involved a coalition of several organizations, but the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was its driving force. In 1960, youth from sit-in movements founded the organization on a shared commitment to non-violent direct action and the empowerment of local communities. Throughout the early 1960s, SNCC developed direct action sit-in strategies, participated in Freedom Rides, started projects throughout the South, and eventually turned its focus to voting rights and voter education.2 SNCC began their activism with sit-ins that tested new integration laws, but they generated an expansive vision of social change, as illustrated in the Summer Project of 1964. From 1961 to 1963, SNCC initiated voter registration drives in Mississippi with little success. Frustrated by the escalating violence and the murders of key allies in the local Mississippi community, Bob Moses suggested that SNCC focus all its resources on Mississippi and reinvigorate its work by recruiting volunteers from a national pool of college students. In 1963, a similar small-scale effort called "The Freedom Vote" involving a few students · from Yale and Stanford had generated significant media attention (Sinsheimer 217-244). -

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964

Mississippi Freedom Summer, 1964 By Bruce Hartford Copyright © 2014. All rights reserved. For the winter soldiers of the Freedom Movement Contents Origins The Struggle for Voting Rights in McComb Mississippi Greenwood & the Mississippi Delta The Freedom Ballot of 1963 Freedom Day in Hattiesburg Mississippi Summer Project The Situation The Dilemma Pulling it Together Mississippi Girds for Armageddon Washington Does Nothing Recruitment & Training 10 Weeks That Shake Mississippi Direct Action and the Civil Rights Act Internal Tensions Lynching of Chaney, Schwerner & Goodman Freedom Schools Beginnings Freedom School Curriculum A Different Kind of School The Freedom School in McComb Impact The Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR) Wednesdays in Mississippi The McGhees of Greenwood McComb — Breaking the Klan Siege MFDP Challenge to the Democratic Convention The Plan Building the MFDP Showdown in Atlantic City The Significance of the MFDP Challenge The Political Fallout Some Important Points The Human Cost of Freedom Summer Freedom Summer: The Results Appendices Freedom Summer Project Map Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer Meeting the Freedom Workers The House of Liberty Freedom School Curriculum Units Platform of the Mississippi Freedom School Convention Testimony of Fannie Lou Hamer, Democratic Convention Quotation Sources [Terminology — Various authors use either "Freedom Summer" or "Summer Project" or both interchangeably. This book uses "Summer Project" to refer specifically to the project organized and led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO). We use "Freedom Summer" to refer to the totality of all Freedom Movement efforts in Mississippi over the summer of 1964, including the efforts of medical, religious, and legal organizations (see Organizational Structure of Freedom Summer for details). -

State of Rhode Island

2002 -- H 6748 ======= LC00855 ======= STATE OF RHODE ISLAND IN GENERAL ASSEMBLY JANUARY SESSION, A.D. 2002 ____________ H O U S E R E S O L U T I O N THANKING ROBERT PARRIS (BOB) MOSES FOR HIS PARTICIPATION AT THE UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND'S EIGHTH ANNUAL LECTURE ON MULTICULTURALISM Introduced By: Representatives Benson, and Carter Date Introduced: January 10, 2002 Referred To: House read and passed 1 WHEREAS, Robert Parris Moses, a mathematics teacher in New York City, began his 2 career as a civil rights activist in 1960. While visiting Virginia, he was inspired by black students 3 at a sit-in. Mr. Moses returned to New York where he participated in a march organized by 4 veteran civil rights activist Bayard Rustin; and 5 WHEREAS, Mr. Moses went on to volunteer with the Southern Christian Leadership 6 Conference which ultimately gave birth to a new youth-oriented organization, the Student Non- 7 Violence Coordinating Committee that stressed grassroots initiatives, cultivation of local 8 leadership and decentralized decision-making; and 9 WHEREAS, In 1961, Mr. Moses left teaching to commit to full-time work in the struggle 10 for civil rights. His career in Mississippi, pivotal to the civil rights movement included 11 emphasiz ing voter registration as a means for empowering low-income blacks, promoting 12 collaboration between various civil rights organizations, mobilizing the Mississippi Freedom 13 Summer Project and the nurturing and development of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic 14 Party; and 15 WHEREAS, After a period as a draft resister against the Vietnam War and as a math 16 teacher in Tanzania in East Africa, Mr.