Based Theatre in 21St Century Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Image: Brian Hartley

IMAGINATE FESTIVAL Scotland’s international festival of performing arts for children and young people 6-13 may 2013 TICKETS:0131 228 1404 WWW.TRAVERSE.CO.UK Image: Brian Hartley IMAGINATE FESTIVAL FUNDERS & SUPPORT ABOUT IMAGINATE Every year Imaginate receives financial and in kind support from a range of national and international organisations.We would like to thank them all for their invaluable support of the Imaginate Festival. Imaginate is a unique organisation in Scotland,leading in the promotion,development If you would like to know more about our supporters or how to support us,please visit: and celebration of the performing arts for children and young people. www.imaginate.org.uk/support/ We achieve this through the delivery of an integrated M A J O R F U N D E R S BEYONDTHE FESTIVAL annual programme of art-form development, learning supported through the partnerships and performance, including the world Imaginate believes that a high quality creative Scottish Government’s Edinburgh Festivals Expo Fund famous Imaginate Festival, Scotland’s international development programme is the key to unlocking festival of performing arts for children and young people. creativity and supporting artistic excellence in the performing arts sector for children and young people in THE IMAGINATE FESTIVAL Scotland. This programme creates regular opportunities for artists and practitioners, whether they are students, T R U S T S A N D F O U N D AT I O N S PA R T N E R S Every year the Festival and Festival On Tour attracts established artists or at the beginning of their career. -

Macbeth Act by Act Study

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE MACBETH NAME:_____________________________________ LIT AO1, AO2, AO3 Act One Scene One The three witches meet in a storm and decide when they will meet up again. AO1: What does the weather suggest to the audience about these characters? _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________ AO2: Why are the lines below important? What do they establish about this play? Fair is foul, and foul is fair: Hover through the fog and filthy air. (from BBC Bitesize): In Shakespeare’s time people believed in witches. They were people who had made a pact with the Devil in exchange for supernatural powers. If your cow was ill, it was easy to decide it had been cursed. If there was plague in your village, it was because of a witch. If the beans didn’t grow, it was because of a witch. Witches might have a familiar – a pet, or a toad, or a bird – which was supposed to be a demon advisor. People accused of being witches tended to be old, poor, single women. It is at this time that the idea of witches riding around on broomsticks (a common household implement in Elizabethan England) becomes popular. King James I became king in 1603. He was particularly superstitious about witches and even wrote a book on the subject. Shakespeare wrote Macbeth -

Edinburgh International Festival Society Papers

Inventory Acc.11779 Edinburgh International Festival Society Papers National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland BOX 1 1984 1. Venue letting contracts. 2. Australian Youth Orchestra. 3. BBC Orchestra. 4. Beckett Clurman. 5. Black Theatre 6. Boston Symphony 7. Brussels Opera 8. Childrens Music Theatre 9. Coleridges Ancient Mariner 10. Hoffung Festival BOX 2 1984 11. Komische Opera 12. Cleo Laine 13. LSO 14. Malone Dies 15. Negro Ensemble 16. Philharmonia 17. Scottish National 18. Scottish Opera 19. Royal Philharmonic 20. Royal Thai Ballet 21. Teatro Di San Carlo 22. Theatre de L’oeuvre 23. Twice Around the World 24. Washington Opera 25. Welsh National Opera 26. Broadcasting 27. Radio Forth/Capital 28. STV BOX 2 1985 AFAA 29. Applications 30. Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra/Netherlands Chamber Orchestra 31. Balloon Festival. 32. BBC TV/Radio. 33. Le Misanthrope – Belgian National Theatre 34. John Carroll 35. Michael Clark. BOX 3 36. Cleveland Quartet 37. Jean Phillippe Collard 38. Compass 39. Connecticut Grand Opera 40. Curley 41. El Tricicle 42. EuroBaroque Orchestra 43. Fitzwilliam 44. Rikki Fulton 45. Goehr Commission 46. The Great Tuna 47. Haken Hagegard and Geoffery Parons 48. Japanese Macbeth 49. .Miss Julie 50. Karamazous 51. Kodo 52. Ernst Kovacic 53. Professor Krigbaum 54. Les Arts Florissants. 55. Louis de France BOX 4 56. London Philharmonic 57. Lo Jai 58. Love Amongst the Butterflies 59. Lyon Opera 60. L’Opera de Nice 61. Montreal Symphony Orchestra 62. -

Boston Guide

what to do U wherewher e to go U what to see July 13–26, 2009 Boston FOR KIDS INCLUDING: New England Aquarium Boston Children’s Museum Museum of Science NEW WEB bostonguide.com now iPhone and Windows® smartphone compatible! oyster perpetual gmt-master ii The moon landing 40th anniversary. See how it Media Sponsors: OFFICIALROLEXJEWELER JFK ROLEX OYSTER PERPETUAL AND GMT-MASTER II ARE TRADEMARKS. began at the JFK Presidential Library and Museum. Columbia Point, Boston. jfklibrary.org StunningCollection of Murano Glass N_Xc\ NXkZ_ E\n <e^cXe[ 8hlXi`ld J`dfej @D8O K_\Xki\ Pfli e\ok Furnishings, Murano Glass, Sculptures, Paintings, X[m\ekli\ Tuscan Leather, Chess Sets, Capodimonte Porcelain Central Wharf, Boston, MA www.neaq.org | 617-973-5206 H:K:CIN C>C: C:L7JGN HIG::I s 7DHIDC B6HH68=JH:IIH XnX`kj telephone s LLL <6AA:G>6;ADG:CI>6 8DB DAVID YURMAN JOHN HARDY MIKIMOTO PATEK PHILIPPE STEUBEN PANERAI TOBY POMEROY CARTIER IPPOLITA ALEX SEPKUS BUCCELLAITI BAUME & MERCIER HERMES MIKIMOTO contents l Jew icia e ff le O r COVER STORY 14 Boston for Kids The Hub’s top spots for the younger set DEPARTMENTS 10 hubbub Sand Sculpting Festival and great museum deals 18 calendar of events 20 exploring boston 20 SIGHTSEEING 30 FREEDOM TRAIL 32 NEIGHBORHOODS 47 MAPS 54 around the hub 54 CURRENT EVENTS 62 ON EXHIBIT 67 SHOPPING 73 NIGHTLIFE 76 DINING on the cover: JUMPING FOR JOY: Kelly and Patrick of Model Kelly and Patrick enjoy the Club Inc. take a break in interactive dance floor in the front of a colorful display Boston Children’s Museum’s during their day of fun at the Kid Power exhibit area. -

Schools Programme

Schools Programme WELCOME A recent study found that children who regularly attended theatre with their school had higher aspirations and better hopes about their future lives. This news sent my heart soaring as this is what this job is all about! The productions presented this year are surprising and eclectic, taking the spectator along visually interesting pathways. The works include a wide variety of theatrical genres from spoken text to puppetry, from dance theatre and musical explorations to acrobatics. Many of the productions are non-text based making them accessible to a broader audience. Central to the Festival are four exciting shows by Scotland based companies as well as a regional focus on Flanders, the Dutch-speaking northern part of Belgium, one of the world’s leaders in producing innovative theatre and dance for young audiences. We have also extended the dates of the Festival to accommodate the increased demand from schools with three international productions opening in the week prior to the main Festival week. In line with our mission, this will allow more children access to high quality theatre. I hope that the 2020 Edinburgh International Children’s Festival is full of special moments for you and your students. Exquisitely theatrical experiences that encourage children and young people to wish, desire and aspire beyond their own lives and immediate neighbourhoods, into their potential future selves. Focus on Flanders supported by: Noel Jordan Festival Director Beyond the Festival: • Creative learning project Imaginate -

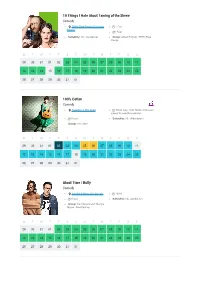

10 Things I Hate About Taming of the Shrew

10 Things I Hate About Taming of the Shrew Comedy PBH's Free Fringe @ Voodoo 17:55 Rooms 1 hour Suitability: 16+ (Guideline) Group: Gillian English / PBH's Free Fringe M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 01 100% Cotton Comedy Paradise in The Vault Times vary. Click 'Dates, times and prices' to view the calendar 1 hour Suitability: 16+ (Restriction) Group: Liz Cotton M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 01 About Time / Bully Comedy Laughing Horse @ City Cafe 19:10 1 hour Suitability: 14+ (Guideline) Group: Sian Davies and Thanyia Moore / Free Festival M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 01 Agatha Is Missing! Comedy Gilded Balloon Teviot 14:30 1 hour Suitability: 12+ (Guideline) Group: Fringe Management, LLC M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 01 Age Fright: 35 and Counting Comedy PQA Venues @Riddle's Court 17:00 50 minutes Suitability: 18+ (Restriction) Group: Jaleelah Galbraith M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 01 Algorithms Theatre Pleasance Courtyard 12:45 1 hour Suitability: 14+ (Guideline) Group: Sadie Clark & Laura Elmes Productions M T W T F S S M T W T F S S 29 30 31 -

S P R I N G 2 0 0 3 Upfront 7 News Politics and Policy Culture And

spring 2003 upfront culture and economy environment 2 whitehall versus wales communications 40 rural survival strategy 62 making development analysing the way Westminster 33 gareth wyn jones and einir sustainable shares legislative power with ticking the box young say we should embrace kevin bishop and unpacking the Welsh 2001 Cardiff Bay robert hazell ‘Development Domains’ as a john farrar report on a census results denis balsom says Wales risks getting the central focus for economic new study to measure our finds subtle connections worst of both worlds policy in the Welsh countryside impact on the Welsh between the language and cover story cover environment 7 news nationality 43 making us better off steve hill calls for the 64 mainstreaming theatre special Assembly Government to renewable energy politics and policy adopt a culture of evaluation peter jones says Wales 13 35 i) a stage for wales in its efforts to improve should move towards clear red water michael bogdanov says Welsh prosperity more sustainable ways of rhodri morgan describes the Cardiff and Swansea living distinctive policy approach should collaborate to developed by Cardiff Bay over science special produce the forerunner europe the past three years for a federal national 47 i) why we need a 15 red green theatre science strategy 66 team wales abroad eluned haf reports on the progressive politics 38 ii) modest venue – phil cooke charts Wales’ adam price speculates on melodramatic progress in venturing into new Welsh representation whether a coalition between debate the -

Download Publication

ARTS COUNCIL CONTENTS C hairina;,'~ Introduction 4 The Arts Council of Great Britain, as a 5 publicly accountable body, publishes an Sui kA• 1r. -C;eneral's Preface 8 Annual Report to provide Parliament and Departmental Report s 14 the general public with an overview of th e Scotland year's work and to record ail grants an d Wales 15 guarantees offered in support of the arts . Council 16 Membership of Council and Staff 17 A description of the highlights of th e Advisory Panels and Committee s 18 Council's work and discussion of its policie s Staff 23 appear in the newspaper Arts in Action Annual Accounts 25 which is published in conjunction with thi s Funds, Exhibitions, SchewsandAuvrd~ Report and can be obtained, free of charge , from the Arts Council Shop, 8 Long Acre , London WC2 and arts outlets throughou t the country . The objects for which the Arts Council of Great Britain is established are : I To develop and improve the knowledge , understanding and practice of the arts ; 2 To increase the accessibility of the arts to the public throughout Great Britain ; 3 To co-operate with governmen t departments, local authorities and othe r bodies to achieve these objects. CHAIRMAN'S INTRODUCTION and performing artists and of helping t o wherever possible both Mth local build up the audiences which must be th e authorities and with private sponsors. real support for the arts . It is the actua l event, the coming together of artist an d The Arts Council is very conscious that th e audience, which matters . -

Annual Report 2000-2001

NATIONAL MUSEUMS & GALLERIES OF WALES report Annual Report of the Council 2000-2001 The President and Council would like to thank the following, and those who wish to remain anonymous, for their generous support of the National Museums & Galleries of Wales in the period from 1st April 2000 to 31st March 2001 Corporate Sponsors 2000 to 2001 Save & Prosper Educational Trust Arts & Business Cymru Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths of London Barclays Anonymous Trust BG Transco plc BT Individual Donors giving in excess of £250 Ceramiks David and Diana Andrews Consignia, formerly The Post Office David and Carole Burnett DCA Mrs Valerie Courage DFTA Designs from the Attic Geraint Talfan Davies Dow Corning Marion Evans ECD Energy and Environment Mrs Christine Eynon GE Aircraft Engines, Inc. Roger and Kathy Farrance Gerald Davies Ltd Michael Griffith GMB G. Wyn Howells Lloyds TSB Commercial David Watson James, OBE Paula Rosa Jane Jenkins The Principality Dr and Mrs T. P. Jones Redrow South Wales Ltd Dr Margaret Berwyn Jones Smartasystems Miss K.P. Kernick Standard Signs The Rt Hon. Neil Kinnock Stannah Dafydd Bowen Lewis Transport & General Workers Union Gerald and Pat Long Unison L. Hefin Looker United Welsh Housing Association Mr Howard Moore Wales Information Society Mrs Rosemary Morgan Wincilate Malcolm and Monica Porter Our 174 partner companies who have ensured Mathew and Angela Prichard the success of the House for the Future at the Alan K.P. Smith Museum of Welsh Life Dr P.M. Smith John and Jane Sorotos Founder and Corporate Members Roger G. Thomas GE Aircraft Engines, Inc. John Foster Thomas Golley Slater Public Relations Mrs Meriel Watkins Interbrew Richard N. -

Lady Macbeth, the Ill-Fated Queen

LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI BY 2015 Andrea Lynn Garritano ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of The University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz ________________________________ Prof. Joyce Castle ________________________________ Dr. John Stephens ________________________________ Dr. Kip Haaheim ________________________________ Dr. Martin Bergee Date Defended: December 19, 2014 ii The Dissertation Committee for ANDREA LYNN GARRITANO Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: LADY MACBETH, THE ILL-FATED QUEEN: EXPLORING SHAKESPEAREAN THEMES OF AMBITION, SEXUALITY, WITCHCRAFT, PATRILINEAGE, AND MATRICIDE IN VOCAL SETTINGS OF VERDI, SHOSTAKOVICH, AND PASATIERI ______________________________ Chairperson, Dr. Roberta Freund Schwartz Date approved: January 31, 2015 iii Abstract This exploration of three vocal portrayals of Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth investigates the transference of themes associated with the character is intended as a study guide for the singer preparing these roles. The earliest version of the character occurs in the setting of Verdi’s Macbeth, the second is the archetypical setting of Lady Macbeth found in the character Katerina Ismailova from -

Information Pack Trustees Welcome

Information Pack Trustees "Since its inception, National Theatre Wales have never been afraid to ask what theatre is and what it might be” The Guardian, UK Welcome. Thank you for your interest in the role of Trustee on the Board of National Theatre of Wales (NTW). NTW collaborates with people and places to make extraordinary theatre that inspires change. We operate from a small base in Cardiff city centre, but the nation of Wales is our stage, and its incredible stories and wealth of talent is our inspiration. The role of the Board, and each of its members, is critical in bringing effective leadership, support and inspiration to the organisation as it enters a new period in its history during challenging times for the arts sector as a whole. We trust that this recruitment pack will give you the relevant information you require on the role plus some further background on NTW and its future. You will find details on how to apply on page 6. The deadline for applications to be received is 12 noon, Wednesday 11th November. Thank you for your interest in NTW and for taking the time to consider joining us. We look forward to hearing from you. Clive Jones, Chair Background National Theatre Wales (NTW) is succession planning for its board of trustees and looking for a number of Non-Executive Directors to join the board from November 2020 onwards. Chaired by Sir Clive Jones CBE since December 2016, the board supports and advances the artistic vision of Lorne Campbell, the new CEO/Artistic Director, who joined the company in March 2020. -

Chicago Shakespeare in the Parks Tour Into Their Neighborhoods Across the Far North, West, and South Sides of the City

ANNOUNCING OUR 2018/2019 SEASON —The Merry Wives of Windsor Explosive, Pulitzer Prize-winning drama. Shakespeare’s tale of magic and mayhem—reimagined. The “76-trombone,” Tony-winning musical The Music Man. And so much more! 5-play Memberships start at just $100. We’re Only Alive For A Short Amount Of Time | How To Catch Creation | Sweat The Winter’s Tale | The Music Man | Lady In Denmark | Twilight Bowl | Lottery Day GoodmanTheatre.org/1819Season 312.443.3800 2018/2019 Season Sponsors MACBETH Contents Chicago Shakespeare Theater 800 E. Grand on Navy Pier On the Boards 10 Chicago, Illinois 60611 A selection of notable CST events, plays, and players 312.595.5600 www.chicagoshakes.com Conversation with the Directors 14 ©2018 Chicago Shakespeare Theater All rights reserved. Cast 23 ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CARL AND MARILYNN THOMA ENDOWED CHAIR: Barbara Gaines EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Playgoer's Guide 24 Criss Henderson PICTURED: Ian Merrill Peakes Profiles 26 and Chaon Cross COVER PHOTO BY: Jeff Sciortino ABOVE PHOTO BY: joe mazza A Scholar’s Perspective 40 The Basic Program of Liberal Education for Adults is a rigorous, non- Part of the John W. and Jeanne M. Rowe credit liberal arts program that draws on the strong Socratic tradition Inquiry and Exploration Series at the University of Chicago. There are no tests, papers, or grades; you will instead delve into the foundations of Western political and social thought through instructor-led discussions at our downtown campus and online. EXPLORE MORE AT: graham.uchicago.edu/basicprogram www.chicagoshakes.com 5 Welcome DEAR FRIENDS, When we first imagined The Yard at Chicago Shakespeare and the artistic capacity inherent in its flexible design, we hoped that this new venue would invite artists to dream big as they approached Shakespeare’s work.