Social Mobilization and Governance of Community Forest in Chitwan, Central Terai, Nepal: a Case Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State Protection – Local Government – Ward Chairmen

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: NPL17502 Country: Nepal Date: 2 September 2005 Keywords: Nepal – Maoists – Chitwan – State protection – Local government – Ward Chairmen This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? 2. Do the Maoists have an office in Chitwan? Letter head paper or contact address? 3. What is a Ward and a Ward Chairman? 4. Is there evidence of the Maoists targeting members of Municipal councils or Ward Chairmen? RESPONSE 1. Can you provide information on the activities of Maoists in Chitwan and the ability of the authorities to provide protection for individuals against threats from Maoists? Activities A December 2002 Research Response provides information on Maoists in Chitwan suggesting it is a quiet area and they are mainly active in remote villages (RRT Country Research 2002 Research Response NPL17502, 24 December, question 1 – Attachment 1). A recent news item from the al Jazeera website refers to the Maoist-controlled district of Chitwan (‘Nepal blast triggers hunt for Maoists’ 2005, al Jazeera website, source: AFP, 6 June http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/9F7BE0A5-E320-4C5B-BD03- 7151D63A574F.htm - accessed 1 September 2005 - Attachment 2). -

Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang

Study on Enterprises for Self Employment in Banke and Dang Prepared for: USAID/Nepal’s Education for Income Generation in Nepal Program Prepared by: EIG Program Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry Shahid Sukra Milan Marg, Teku, Kathmandu May 2009 TABLE OF CONTENS Page No. Acknowledgement i Executive Summary ii 1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 9 2 Objective of the Study ....................................................................................................... 9 3 Methodology ...................................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Desk review ............................................................................................................... 9 3.2 Focus group discussion/Key informant interview ..................................................... 9 3.3 Observation .............................................................................................................. 10 4 Study Area ....................................................................................................................... 10 4.1 Overview of Dang and Banke district ...................................................................... 10 4.2 General Profile of Five Market Centers: .................................................................. 12 4.2.1 Nepalgunj ........................................................................................................ -

Krishna Kaphle, Bvsc and AH,,GHC, ELT, Phd

Krishna Kaphle, BVSc and AH,,GHC, ELT, PhD Current Position: Director, Veterinary Teaching Hospital and As- sociate Professor at Department of Theriogenology Institution: Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science Tribhuvan University, Paklihawa Campus, Sidharthanagar-1, Rupandehi, Lumbini, Nepal E-mails and phone: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Phone: : +977-71-506150; Cell: 9845056734 Research Interest: ONE HEALTH ADVOCATING VETERINARIAN (THERIOGENOLOGIST) Objective: In pursuit of establishing best approach for delivery of animal health, animal welfare and public health concerns in Nepalese society. Get deeper in understanding the science behind origin of life. Beliefs: Engaged faculty and motivated student make the teach- ing and learning meaningful and nothing transform society bet- ter than right education. MAJOR ROLES, RESPONSIBILITIES AND PUBLICATIONS Education Aug 2001 – May 2006 (PhD) -National Taiwan University,, Taipei, Tai- wan, Republic Of China (ROC). Aug 1991 – 1997 (BVSc and AH) -Rampur Campus, Institute of Agri- culture and Animal Science (IAAS), Tribhuvan University (TU), Bharat- pur, Chitwan, Bagmati, Nepal. Responsibilities Assistant Professor: since 2055-01-15 at Rampur Campus, IAAS, TU. Hostel Warden, Sports Coach, Student Welfare Chief, member of various committees, at IAAS, TU. Advisory role for various students clubs, coordinator of national and regional events related with professional, sports and leadership training. Editorial roles for IAAS Journal, NVA Journal, The Blue Cross and multiple others. Department Head of Theriogenology- (April 10th 2009 and again from July 2021), IAAS, TU. Stints as Member secretary Internship Advisory Committee, Subject Matter Com- mittee (Veterinary Science) now as member, Member of Faculty Board (2018-). Advisor of Internship students (~20) and PG students as minor advisor (10). -

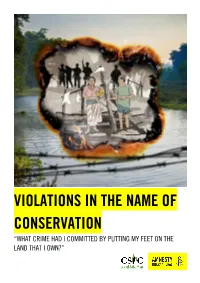

Violations in the Name of Conservation “What Crime Had I Committed by Putting My Feet on the Land That I Own?”

VIOLATIONS IN THE NAME OF CONSERVATION “WHAT CRIME HAD I COMMITTED BY PUTTING MY FEET ON THE LAND THAT I OWN?” Amnesty International is a movement of 10 million people which mobilizes the humanity in everyone and campaigns for change so we can all enjoy our human rights. Our vision is of a world where those in power keep their promises, respect international law and are held to account. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and individual donations. We believe that acting in solidarity and compassion with people everywhere can change our societies for the better. © Amnesty International 2021 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Illustration by Colin Foo (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Photo: Chitwan National Park, Nepal. © Jacek Kadaj via Getty Images https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2021 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 31/4536/2021 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1.1 PROTECTING ANIMALS, EVICTING PEOPLE 5 1.2 ANCESTRAL HOMELANDS HAVE BECOME NATIONAL PARKS 6 1.3 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY THE NEPAL ARMY 6 1.4 EVICTION IS NOT THE ANSWER 6 1.5 CONSULTATIVE, DURABLE SOLUTIONS ARE A MUST 7 1.6 LIMITED POLITICAL WILL 8 2. -

Gunjaman Singh Hospital, Pithuwa Village, Chitwan District, Nepal

Gunjaman Singh Hospital, Pithuwa Village, Chitwan District, Nepal GGHH Agenda Goals Energy Hospital Goals 1. Reduce energy costs 2. Reduce carbon dioxide emissions 3. Continue to treat patients during power cuts Progress Achieved Our solar panel installation (Photo below) is working perfectly. With careful power management we have enough electric power, for the hospital and doctors’ quarters even during load shedding (power outages) of sometimes up to 18 hours per day. This includes power for the x-ray machine and the waste autoclave. We have completely CO 2 free energy and low energy cost for loading batteries sometimes when there isn’t enough sunshine. The cost of installation for sixteen panels, the inverter and the sixteen batteries of 100Ah system was around 12,000 CHF (US$13,000) in 2010; prices have dropped since The Issue The hospital is funded by Swiss NGO “Shanti Med Nepal” and private sponsorship. Environmental health and sustainability is an important factor in decisions in the development in the hospital. Sustainability Strategy Implemented Solar energy was installed as a priority for the hospital as soon as Shanti Med became involved in its operation. Implementation process In such a small facility, the decision making and implementation process is comparatively simple. Dr Gonseth was responsible for selecting the projects to be undertaken, any necessary fundraising, identifying collaboration partners and directing implementation for all elements within GSH. Tracking Progress Solar power: success is measured by the ability of the system to produce all the electricity required by the health post and staff quarters. The level of power in the battery system is recorded and allows demand to be managed through the day. -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

INTRODUCTION Social and Economic Benefi Ts

60/ The Third Pole SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT OF TOURISM IN SAURAHA CHITWAN, NEPAL Tej Prasad Sigdel Teaching Assistant, Department of Geography Education, T. U., Nepal Abstract In Nepal, the number of tourist arrivals and stay their length have been increasing day to day. This incensement has directly infl uenced the socio-economic status of Nepalese people. The main objective of this paper is to explore the socio- economic impact of tourism on Sauraha. To fulfi ll the objective both primary and secondary data had been used. There are both direct and indirect impacts on socio-economic condition of local people. Tourism has contributed a lot a raising the awareness among the communities, preserving traditional culture, values, norms and heritage. But it is also facing a problem of sanitation, improper solid waste management, unmanaged dumping site and poaching wild life. Tourism development in Sauraha should be assessed both the local traditions and culture. Key Words: Tourism, socio-economic impact, World Heritage Site, sustainable development INTRODUCTION social and economic benefi ts. Economic benefi ts are, increased government revenue through various In general term, ‘tourism’ denotes the journey of types of taxation, create a jobs and increase family human beings from one place to the another, where and community income, provide the opportunity it may be within own country or second countries for for innovation and creativity, provides the support various purposes. The word ‘Tourism’ which was th for existing business and services, helps to develop originated in the 19 century and was popularized local crafts and trade and develop international in 1930s, but its signifi cance was not fully realized peace and understanding. -

Factors Influencing Organic Farm Income in Chitwan District of Nepal

Factors influencing organic farm income in Chitwan district of Nepal By Mrinila Singh, Keshav Lall Maharjan and Bijan Maskey Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation (IDEC), Hiroshima University, Japan Premium price is one of the most attractive features of organic farming but having access to one possess various difficulties, especially in the context of developing countries. The objective of this study is to analyze factors impacting involvement in marketing of crops and intensity of income generation therein between organic and conventional farmers by taking into consideration the existence of premium market. It was conducted in semi-urban Chitwan district of Nepal where group conversion to organic farming exists. Data from 285 respondents, selected using stratified sampling method, were analyzed using probit and ordinary least square model. This study finds that income from organic farming is less than conventional farming because production per hectare, commercialization rate and price at which the crops are sold per unit is higher for conventional farm, and access to premium market is very limited. This should be the primary focus for making organic farming monetarily attractive. 1. Introduction Nepal is predominantly an agriculture-based economy that accounts for 36% of the gross domestic product (GDP) and employs 66% of the 26.5 million people (MoAD, 2015). Therefore, the progress in this sector is very much essential for improving lives of the majority and for the development of the economy as a whole. Among others, monetary benefit is one of the major driving forces for the farmers as it provides resources to re/invest in not just farming activities but other sectors such as education and health as well which ultimately improves their living standard. -

A Case from Chitwan District of Nepal

SAARC J. Agri., 16(2): 129-141 (2018) DOI: https://doi.org/10.3329/sja.v16i2.40265 SURVEY ON USAGE OF MEDICINAL PLANTS: A CASE FROM CHITWAN DISTRICT OF NEPAL A. Joshi*, D. Kalauni and S. Bhattarai Faculty of Agriculture, Agriculture and Forestry University, Rampur, Chitwan, Nepal ABSTRACT The aim of this study was to know the commonly available medicinal plants and to document their usages. Study was carried out around periphery of 'Gyaneswor Community Forest' of Bharatpur-16 of Chitwan district of Nepal. Altogether, forty household were selected by random sampling, and key informant interview was carried out with community forest personnel's and leading farmers. Most of the respondents of Bharatpur-16 were found to be dependent on medicinal plants for their primary health care. Because of no side effect, easy availability and cost effectiveness of medicinal plants, most people were found satisfied using it. However, the use of and preference for medicinal plant was found limited to minor diseases only. The findings of this study revealed that there are many medicinal plants in our periphery that can be used as an alternative for allopathic medicines, but they need to be systematically managed and conserved. Keywords: Allopathic; Ayurvedic; Cultivation; Community forest; Medicine; Processing INTRODUCTION Nepal consists of vast biological diversity. It is ranked as 31st richest country in the world, in terms of biodiversity and 10th richest country in the Asia region (MoAD, 2017). Despite of its small coverage area in world map, the unique and rich geography, ecology and climatic condition is attributed due to the wide altitudinal range that measures from about 60 m in plains to 8848 m to the top of the world. -

2 Chitwan District: Asset Baseline

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 44168-012 Capacity Development Technical Assistance (CDTA) October 2013 Nepal: Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development (Financed by the Strategic Climate Fund) District Baseline Reports: Department of Water Supply and Sewerage (DWSS) – Urban Watsan Chitwan, Dolakha, and Kathmandu Districts Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. MOSTE | Mainstreaming climate change risk management in development | WATSAN-Urban district baselines TA – 7984 NEP October, 2013 Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development 1 Main Consultancy Package (44768-012) CHITWAN DISTRICT BASELINE: DEPARTMENT OF WATER SUPPLY AND SEWERAGE (DWSS) – URBAN WATSAN Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management METCON Consultants APTEC Consulting Prepared for Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, Government of Nepal Environment Natural Resources and Agriculture Department, South Asia Department, Asian Development Bank Version B i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 CHITWAN DISTRICT .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Chitwan Sector Master Plan ........................................................................................... -

Features of Small Holder Goat Farming from Chitwan District of Bagmati

Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science 6(2): 186-193 (2021) https://doi.org/10.26832/24566632.2021.0602010 This content is available online at AESA Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science Journal homepage: journals.aesacademy.org/index.php/aaes e-ISSN: 2456-6632 ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE Features of small holder goat farming from Chitwan district of Bagmati province in Nepal Alok Dhakal1 , Sujit Regmi1, Meena Pandey1* , Teknath Chapagain1 and Krishna Kaphle2 1Paklihawa Campus, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Tribhuvan University, Rupandehi, Lumbini, NEPAL 2Associate Professor and Director, Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Paklihawa Campus, Institute of Agriculture and Animal Science, Tribhuvan University, Rupandehi, Lumbini, NEPAL *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received: 01 April 2021 An assessment was done to analyze the status of small scale goat production system in Revised received: 12 May 2021 Chitwan, Nepal. A semi-structured questionnaire having both open ended and close ended Accepted: 15 June 2021 questions were interviewed to 147 farmers (69 males, 78 females). The average goat holding was 5.48±0.15 head with female: male ratio of 6: 5. Mainly women folks in the household were involved in husbandry of the raised goats. In this research, we realized that goats were a Keywords valuable commodity for the community in the survey area. Grazing in public forest, fallow Assessment lands, tree leaves, shrubs and bushes were the main sources of feed for goats throughout the Goat year. When inquired about vaccination, 92.51% of the farmers did not vaccinate their goats Husbandry and were not aware about its importance. -

Chitwan District Vulnerability Assessment Report

TA – 7984 NEP April, 2014 Mainstreaming Climate Change Risk Management in Development 1 Main Consultancy Package (44768-012) WATSAN – CHITWAN DISTRICT VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT REPORT Prepared by ICEM – International Centre for Environmental Management METCON Consultants APTEC Consulting Prepared for Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment, Government of Nepal Environment Natural Resources and Agriculture Department, South Asia Department, Asian Development Bank Version B (Draft for Comment) MOSTE | Mainstreaming climate change risk management in development | WATSAN - Chitwan District – VA Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 DISTRICT ASSETS/SYSTEM PRIORITIES .............................................................................. 1 1.1 Chitwan District WATSAN Infrastructure ........................................................................ 1 1.2 Vulnerability Assessments .............................................................................................. 1 2 VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT METHOD ............................................................................ 3 2.1 VA Method ...................................................................................................................... 3 2.2 Suitability of VA Method to WATSAN Sector .................................................................. 5 2.3 Climate Change Threat Profiles ....................................................................................... 6 3 VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT RESULTS ...........................................................................