This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D4 DEACCESSION LIST 2019-2020 FINAL for HLC Merged.Xlsx

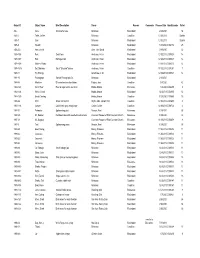

Object ID Object Name Brief Description Donor Reason Comments Process Date Box Barcode Pallet 496 Vase Ornamental vase Unknown Redundant 2/20/2020 54 1975-7 Table, Coffee Unknown Condition 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-7 Saw Unknown Redundant 12/12/2019 Stables 1976-9 Wrench Unknown Redundant 1/28/2020 C002172 25 1978-5-3 Fan, Electric Baer, John David Redundant 2/19/2020 52 1978-10-5 Fork Small form Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-7 Fork Barbeque fork Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-9 Masher, Potato Anderson, Helen Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1978-10-16 Set, Dishware Set of "Bluebird" dishes Anderson, Helen Condition 11/12/2019 C001351 7 1978-11 Pin, Rolling Grantham, C. W. Redundant 12/12/2019 C001523 14 1981-10 Phonograph Sonora Phonograph Co. Unknown Redundant 2/11/2020 1984-4-6 Medicine Dr's wooden box of antidotes Fugina, Jean Condition 2/4/2020 42 1984-12-3 Sack, Flour Flour & sugar sacks, not local Hobbs, Marian Relevance 1/2/2020 C002250 9 1984-12-8 Writer, Check Hobbs, Marian Redundant 12/3/2019 C002995 12 1984-12-9 Book, Coloring Hobbs, Marian Condition 1/23/2020 C001050 15 1985-6-2 Shirt Arrow men's shirt Wythe, Mrs. Joseph Hills Condition 12/18/2019 C003605 4 1985-11-6 Jumper Calvin Klein gray wool jumper Castro, Carrie Condition 12/18/2019 C001724 4 1987-3-2 Perimeter Opthamology tool Benson, Neal Relevance 1/29/2020 36 1987-4-5 Kit, Medical Cardboard box with assorted medical tools Covenant Women of First Covenant Church Relevance 1/29/2020 32 1987-4-8 Kit, Surgical Covenant -

Bibliography

Professor Peter Henriques, Emeritus E-Mail: [email protected] Recommended Books on George Washington 1. Paul Longmore, The Invention of GW 2. Noemie Emery, Washington: A Biography 3. James Flexner, GW: Indispensable Man 4. Richard Norton Smith, Patriarch 5. Richard Brookhiser, Founding Father 6. Marcus Cunliffe, GW: Man and Monument 7. Robert Jones, George Washington [2002 edition] 8. Don Higginbotham, GW: Uniting a Nation 9. Jack Warren, The Presidency of George Washington 10. Peter Henriques, George Washington [a brief biography for the National Park Service. $10.00 per copy including shipping.] Note: Most books can be purchased at amazon.com. A Few Important George Washington Web sites http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/henriques/hist615/index.htm [This is my primitive website on GW and has links to most of the websites listed below plus other material on George Washington.] www.virginia.edu/gwpapers [Website for GW papers at UVA. Excellent.] http://etext.virginia.edu/washington [The Fitzpatrick edition of the GW Papers, all word searchable. A wonderful aid for getting letters on line.] http://georgewashington.si.edu [A great interactive site for students of all grades focusing on Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait of GW.] http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/presiden/washpap.htm [The Avalon Project which contains GW’s inaugural addresses and many speeches.] http://www.mountvernon.org [The website for Mount Vernon.] Additional Books and Websites, 2004 Joe Ellis, His Excellency, October 2004 [This will be a very important book by a Pulitzer winning -

Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War

History in the Making Volume 9 Article 5 January 2016 Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War Heather K. Garrett CSUSB Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making Part of the United States History Commons, and the Women's History Commons Recommended Citation Garrett, Heather K. (2016) "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making: Vol. 9 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/history-in-the-making/vol9/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in History in the Making by an authorized editor of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Articles Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spies: Women and the Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War By Heather K. Garrett Abstract: When asked of their memory of the American Revolution, most would reference George Washington or Paul Revere, but probably not Molly Pitcher, Lydia Darragh, or Deborah Sampson. Therefore, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate not only the lack of inclusivity of women in the memory of the Revolutionary War, but also why the women that did achieve recognition surpassed the rest. Women contributed to the war effort in multiple ways, including serving as cooks, laundresses, nurses, spies, and even as soldiers on the battlefields. Unfortunately, due to the large number of female participants, it would be impossible to include the narratives of all of the women involved in the war. -

Full Text (PDF)

International Journal of Art and Art History December 2019, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 39-52 ISSN: 2374-2321 (Print), 2374-233X (Online) Copyright © The Author(s).All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijaah.v7n2p4 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/ijaah.v7n2p4 The Black Image in the English Gaze: Depictions of Blackness in English Art Tony Frazier1 Abstract: This paper analyzes English art to view the black experience in the eighteenth-century. English painters placed black people into their portraits in various stations of life throughout the period. The fashioning and placement of black people in English art renders for the reader some interpretation how English artists used the black body in their paintings. These images of blacks emerged from the imaginations of white artists; thusly these portraits and prints are not from the black perspective of English society, but a reflection of white attitudes. Therefore, a certain caution exists in any interpretation of the paintings. The inference about the implications of the paintings develops from the gaze of white artists. This paper suggests that an interpretation through English art does reveal something about the status of black people and shed light on satirical explanations of race and sex in eighteenth-century England. Keywords: William Hogarth, Black British Art, George Moorland, Richard Cosway, British Painters, Frances Villiers In the minds of many white Londoners of the eighteenth century, blacks were very present in society. White Londoners in fact constructed their own images of blacks, which in many ways related to social reality of the day. -

Fall 2005 — Vol

W&M CONTENTS FALL 2005 — VOL. 71, NO. 1 FEATURES 37 2005 ALUMNI 42 MEDALLION RECIPIENTS BY MELISSA V. PINARD AND JOHN T. WALLACE 42 JUSTICE FOR ALL Kaign Christy J.D. ’83 Defends Children from Sex Slavery in Cambodia BY DAVID MCKAY WILSON 48 EGYPT TO INXS Nancy Gunn’s ’88 Career in Reality Television Y ’96 BY MELISSA V. PINARD 50 PROTESTS ... HERE? At William and Mary Civil Discourse Ultimately Prevails BY JAMES BUSBEE ’90 SEPH CAMPANELLA CLEAR SEPH CAMPANELLA O 54 WILLIAM AND MARY’S FAVORITE ARCHITECT Kaign Christy J.D. ’83, the Interna- tional Justice Mission’s director of Sir Christopher Wren Rebuilds overseas field presence in Cambodia, London for the Monarchs is at the forefront of the battle against child prostitution in Southeast Asia. BY CHILES T.A. LARSON ’53 These rescued victims’ eyes are blurred to protect their identities. DEPARTMENTS /TED HADDOCK; BOTTOM PHOTO: J 5 UP FRONT 65 CLASS NOTES 7 MAILBOX 114 VITAL STATS MISSION 22 9 AROUND THE WREN 126 WHO, WHAT, WHERE 15 VIEWPOINT 128 CIRCA 17 ALUMNI SPIRIT SPECIAL SECTION: TIONAL JUSTICE TIONAL A HONOR ROLL OF DONORS 22 JUST OFF DOG STREET 25 ARTS & HUMANITIES ON THE COVER: A period drawing of the exterior Joseph Campanella 29 TRIBE SPORTS of London’s Chelsea Hospital, designed by Sir Cleary ’96 masters the art of mandolin making. Christopher Wren. IMAGE COURTESY OF COLONIAL 34 PHILANTHROPY TOP PHOTO: INTERN WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2005 3 UPFRONT ToBe Public and Great or several weeks now, I have Unsurprisingly, perhaps, I have my own occupied what must be one of inclinations. -

National US History Bee Round #1

National US History Bee Round 1 1. This group had a member who used the alias “Robert Rich” when writing The Brave One and who had previously written the anti-war novel Johnny Get Your Gun. This group was vindicated when member Dalton Trumbo received a credit for the movie Spartacus. Who were these screenwriters cited for contempt of Congress and blacklisted after refusing to testify before the anti-Communist HUAC? ANSWER: Hollywood Ten 052-13-92-01101 2. This man is seen pointing to a curiously bewigged child in a Grant Wood painting about his “fable.” This man invented a popular story in which a father praises the “act of heroism” of his son when the latter insists “I cannot tell a lie” after cutting down a cherry tree. Who is this man who invented numerous stories about George Washington for an 1800 biography? ANSWER: Parson Weems [or Mason Locke Weems] 052-13-92-01102 3. This building is depicted in Charles Wilson Peale’s self-portrait The Artist in His Museum. This building is where James Wilson proposed a compromise in a meeting convened after the Annapolis Convention suggested revising the Articles of Confederation. What is this Philadelphia building, the site of the Constitutional Convention? ANSWER: Independence Hall [or Old State House of Pennsylvania] 052-13-92-01103 4. This event's completion resulted in Major Ridge and Elias Boudinot's assassination by dissidents. This event was put into action after the Treaty of New Echota was signed. This event began at Red Clay, Tennessee, and many participants froze to death at places like Mantle Rock. -

America the Beautiful Part 1

America the Beautiful Part 1 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 1 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-141-8 Copyright © 2020 Notgrass Company. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Jordan Pond, Maine, background by Dave Ashworth / Shutterstock.com; Deer’s Hair by George Catlin / Smithsonian American Art Museum; Young Girl and Dog by Percy Moran / Smithsonian American Art Museum; William Lee from George Washington and William Lee by John Trumbull / Metropolitan Museum of Art. Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of Denali in Denali National Park. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History 975 Roaring River Rd. Gainesboro, TN 38562 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Thunder Rocks, Allegany State Park, New York Dear Student When God created the land we call America, He sculpted and painted a masterpiece. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/scholarly-editions-and-translations-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Institution: Princeton University Project Director: Barbara Bowen Oberg Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Statement of Significance and Impact of Project This project is preparing the authoritative edition of the correspondence and papers of Thomas Jefferson. Publication of the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1950 kindled renewed interest in the nation’s documentary heritage and set new standards for the organization and presentation of historical documents. Its impact has been felt across the humanities, reaching not just scholars of American history, but undergraduate students, high school teachers, journalists, lawyers, and an interested, inquisitive American public. -

Social Washington's Evolution from Republican Court to Self-Rule, 1801-1831 Merry Ellen Scofield Wayne State University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Digital Commons@Wayne State University Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2014 Assumptions Of Authority: Social Washington's Evolution From Republican Court To Self-Rule, 1801-1831 Merry Ellen Scofield Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Recommended Citation Scofield, Merry Ellen, "Assumptions Of Authority: Social Washington's Evolution From Republican Court To Self-Rule, 1801-1831" (2014). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 1055. This Open Access Embargo is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. ASSUMPTIONS OF AUTHORITY: SOCIAL WASHINGTON'S EVOLUTION FROM REPUBLICAN COURT TO SELF-RULE, 1801-1831 by MERRY ELLEN SCOFIELD DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2014 MAJOR: HISTORY Approved by: ______________________________________ Advisor Date ______________________________________ ______________________________________ ______________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY MERRY ELLEN SCOFIELD 2014 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Both Oakland University and Wayne State have afforded me the opportunity of working under scholars who have contributed either directly or indirectly to the completion of my dissertation and the degree attached to it. From Oakland, Carl Osthaus and Todd Estes encouraged and supported me and showed generous pride in my small accomplishments. Both continued their support after I left Oakland. There is a direct path between this dissertation and Todd Estes. -

Information Taken from Collegeboard.Org August 2020

Information Taken from Collegeboard.org August 2020 Colleges which MAY provide credit for qualified CLEP exams - May be out of date https://clep.collegeboard.org/school-policy-search ALWAYS - verify information on CollegeBoard & at your designated college Alabama College Address Phone Civilian Associate Degree Program 60 W. Shumacher Avenue, Maxwell AFB, Alabama 36112 call Air University (Civilians ONLY, no Military)(334) 469-3233 1 Air University (Civilians ONLY, no Military) 2 Alabama A&M University P O Box 549 Normal, Alabama 35762 call Alabama A&M University256-372-5635 3 Alabama State University 915 South Jackson Street Montgomery, Alabama 36104 4 Athens State University 300 N. Beaty Street Athens, Alabama 35611 call Athens State University(256) 233-8130 5 Auburn University - Montgomery 7440 East Drive Montgomery, Alabama 36117 call Auburn University - Montgomery(334) 244-3796 6 Calhoun Community College ATTN: Admissions and Records PO Box 2216, Decatur, Alabama 35759 call Calhoun Community College(256) 306-2609 7 Central Alabama CC - Childressburg 34091 US Highway 280 Childersburg, Alabama 35044 8 Chattahoochee Valley Community College 2602 College Drive Phenix City, Alabama 36869 call Chattahoochee Valley Community College(334) 291-4996 9 Columbia Southern University 21982 University Lane Orange Beach, Alabama 36561 call Columbia Southern University(800) 977-8449 10 Community College of the Air Force (Active Military ONLY, no civilians) 100 South Turner Boulevard Montgomery, Alabama 36114 call Community College of the Air Force (Active Military ONLY, no civilians)(334) 649-5066 11 Faulkner University 5345 Atlanta Highway GNL University Testing Center, Montgomery, Alabama 36109-3398 call Faulkner University334 - 386 - 7209 12 Gadsden State Community College P.O. -

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania WASHINGTON by JOSEPH WRIGHT, 1784 the Pennsylvania Magazine of HISTORY and BIOGRAPHY

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania WASHINGTON BY JOSEPH WRIGHT, 1784 THE Pennsylvania Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY The Powel Portrait of Washington by Joseph Wright N THE EARLY 1930's when the selection of the best likeness of Washington for official use during the Washington Bicentennial I was being made, the choice narrowed down to a portrait painted by Joseph Wright for Mrs. Samuel Powel and the bust by Houdon. Though the experts agreed that the portrait was probably the better likeness, the bust was selected since it had long been nationally known. The portrait, on the other hand, had never been on public display and had been seen only by generations of Powels and their friends.1 It was not until the 1930's that it emerged from that state of privacy. Its history dates back to the autumn of 1783 and the arrival at Washington's headquarters at Rocky Hill, near Princeton, New Jersey, of a young artist, Joseph Wright. Born in nearby Borden- town in 1756, the son of Patience Wright, who was probably America's first sculptress, Wright had accompanied his mother to England in 1772. There he studied painting under Benjamin West 1 John C. Fitzpatrick, editor of The Writings of George Washington, told Mr. Powel this anecdote. Robert J. H. Powel, Notes on the "Wright" Portrait of General George Washington, copy provided by the Newport Historical Society. 419 420 NICHOLAS B. WAINWRIGHT October and John Hoppner, who married his sister. After a brief stay in France, where he painted Franklin, he returned to America intent on capturing a likeness of Washington. -

Johann Zoffany, Classical Art, Italy and Russian Patronage: Shedding New Light on Models, Men and Paintings

664 Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari УДК 7.034(410.1)8 ББК 85.03 DOI:10.18688/aa155-7-72 Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari Johann Zoffany, Classical Art, Italy and Russian Patronage: Shedding New Light on Models, Men and Paintings Antiquity was the great theme in European art and culture in the second half of the 18th century. Johann Zoffany’s (1733–1810) famous painting of theTribuna of the Uffizi (Royal Collections, UK, Ill. 112) made in Florence between 1772 and 1777, does not portray that room as it was, but sums up a number of classical models of paramount importance in the artistic and social education of any well-bred eighteenth-century European. The astonishing concentration of masterpieces in the Tribuna was a sum of the ideas of beauty selected from antiquity and the Renaissance, even if, considering the first, Rome was undoubtedly the place to go to discover and experience the antique in eighteenth-century Europe. Zoffany himself had discovered classical heritage while living in Rome, from 1750 to 1757 and being a pupil of Anton Raphael Mengs who was, together with Johann Joachim Winckelmann, the main testimonial of antiquity’s values and models. It was in Rome that Zoffany approached the composite community of Grand Tourists who probably showed him how much England was becoming the center of modern Europe and contributed to his decision to move there [8, p. 18] 1. Zoffany’s Classical education is very well shown by a painting he executed in 1753 — in Rome, or perhaps the reason for a short return to Germany — I’m pointing to the Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (Regensburg, Museen der Stadt) [14, p.