A Sustainable Transport Blueprint for Canterbury

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chartham Parish Council

Page 072 2018/2019 CHARTHAM PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD AT 7.30 P.M. ON TUESDAY 12th MARCH 2019 AT THE VILLAGE HALL, STATION ROAD, CHARTHAM, NR CANTERBURY, KENT, CT4 7JA. Present: Cllr. C. Manning – Chairman Cllr. S. Hatcher – Vice Chairman Cllr. S. Dungay Cllr. A. Frost Cllr. D. Butcher Cllr. G. Hoare (left at 9.30pm) Cllr. P. Coles Cllr. L. Root Cllr. T. Clark Cllr. R. Thomas CCC/KCC Cllr. R. Doyle CCC (left at 9.43pm) Miss C. Sparkes (Clerk) 3 Members of the Public (1) Chairman’s Opening Remarks and Apologises for Absence: The Chairman welcomed everyone to the meeting and asked for apologies for absence. These were recorded as Cllr. A. Hopkins (Illness) and Cllr. R. Mallet (Work Commitments). (2) Confirmation of previous Minutes of the last meeting held 12th February 2019: Cllr Hatcher proposed and Cllr Butcher seconded, and all councillors voted in favour, that the Minutes of the parish council meeting held on 12th February 2019 (previously circulated) be accepted as a true record of the meeting and the Chairman duly signed them. (3) Council: a) Declaration of any councillor’s interest in agenda items. None Declaration of Disclosable Pecuniary Interests and Other Significant Interests and Voluntary Announcements of Other Interests, and a reminder to think of any changes to the DPI Register held at CCC, such as a change of job or home. No change to any councillors DPI Register details. (4) Matters Arising from the Minutes: Cllr Manning reported that Robin Baker, who has been instructed to paint the changing rooms, has not provided a copy of his insurance and the dates previously set to undertake the works were cancelled as other jobs Mr Baker had been instructed on took priority. -

Appeal Decision

Appeal Decision Inquiry Held between 30 July and 7 August 2019 Site visits made on 29 July and 2 August 2019 by John Felgate BA(Hons) MA MRTPI an Inspector appointed by the Secretary of State Decision date: 3rd September 2019 Appeal Ref: APP/J2210/W/18/3216104 Land off Popes Lane, Sturry, Kent CT2 0JZ • The appeal is made under section 78 of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 against a refusal to grant outline planning permission. • The appeal is made by Gladman Developments Limited against the decision of Canterbury City Council. • The application Ref 18/01305, dated 22 June 2018, was refused by notice dated 24 September 2018. • The development proposed is the erection of up to 140 Dwellings, with public open space, landscaping, sustainable drainage system, and vehicular access. Decision 1. The appeal is dismissed. Preliminary Matters General 2. The appeal proposal is for outline permission with all details reserved except for access. In so far as the submitted Framework Plan includes details of other elements, including the type and disposition of the proposed open space and planting, it is agreed that these details are illustrative. 3. During the inquiry, a Section 106 planning agreement was completed. The agreement secures the provision of affordable housing and the proposed on- site open spaceRichborough and sustainable urban drainage Estates (SUDs) system, and a system of travel vouchers for future house purchasers. It also provides for financial contributions to schools, libraries, community learning, healthcare, adult social care, youth services, highways, cycle routes, public rights of way, traffic regulation orders (TROs), and ecological mitigation. -

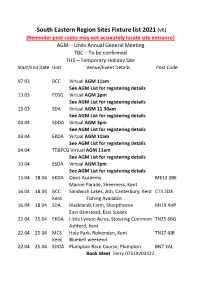

South Eastern Region Sites Fixture List 2021 (V6)

-South Eastern Region Sites Fixture list 2021 (v6) (Reminder post codes may not accurately locate site entrance} AGM – Units Annual General Meeting TBC – To be confirmed THS – Temporary Holiday Site Start/End Date Unit Venue/Event Details Post Code 07.03 BCC Virtual AGM 11am See AGM List for registering details 13.03 FDSG Virtual AGM 3pm See AGM List for registering details 13.03 SDA Virtual AGM 11.30am See AGM List for registering details 03.04 SDDA Virtual AGM 3pm See AGM List for registering details 03.04 EKDA Virtual AGM 11am See AGM List for registering details 04.04 TT&FCG Virtual AGM 11am See AGM List for registering details 10.04 ESDA Virtual AGM 2pm See AGM List for registering details 15.04 18.04 EKDA Oasis Academy ME12 2BE Marine Parade, Sheerness, Kent 16.04 18.04 BCC Sandwich Lakes, Ash, Canterbury, Kent CT3 2DA Kent Fishing Available 16.04 18.04 SDA Blacklands Farm, Sharpthorne RH19 4HP East Grinstead, East Sussex 22.04 25.04 EKDA Little Lynton Acres, Stowting Commom TN25 6BG Ashford, Kent 22.04 25.04 MCS Hole Park, Rolvenden, Kent TN17 4JB Kent Bluebell weekend 22.04 25.04 SDDA Plumpton Race Course, Plumpton BN7 3AL Book Meet Terry 07519203422 23.04 25.04 BCC Kent Fir Tree Farm, Rhodes Minnis, Kent CT4 6XR 29.04 04.05 MCS Orchard Farm, Chidham, Bosham PO18 8PP Southern West Sussex. PH/Bus close by BHM 29.04 03.05 EKDA Jemmet Farm, Mersham, Kent BHM TN25 7HB 29.04 04.05 MCS Kent Quex Park, Birchington, Kent BHM CT7 0BH 29.04 04.05 SDA Pierrepont Farm, Tilford, Surrey BHM GU10 3BS 29.04 03.05 ESDA Laughing Fish, Isfield, -

Prehistoric Settlement Patterns on the North Kent Coast Between Seasalter and the Wantsum

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 129 2009 PREHISTORIC SETTLEMENT PATTERNS ON THE NORTH KENT COAST BETWEEN SEASALTER AND THE WANTSUM TIM ALLEN The area of the north Kent coast addressed in the following study comprises the London Clay-dominated coastal flats, levels and low hills lying north of the Blean, west of the Wantsum Channel and east of Seasalter Level (Map 1). The area measures approximately 15km (10 miles) east-west and 4km (2½ miles) north-south, this representing 60km2. Archaeological remains dating from the Mesolithic to the Roman period were examined with the intention of determining whether significant changes in settlement/ occupation patterns could be discerned over this protracted period and, if so, whether the factors underlying those changes could be identified. A total of 32 sites were investigated and are listed below (Reculver, despite its Late Iron Age origin, has been excluded because of its largely military function during the Roman period, see Rivet and Smith 1981, 446-7; Philp 1959, 105). The statistical evidence derived from the sites is necessarily indicative rather than precise and, as new sites are constantly being uncovered, the list cannot be fully comprehensive. It is also probable that some of the sites represent parts of the same large, widespread settlements, others evidence of relatively transient occupation activity. Despite this it is proposed that the sample is large enough for significant conclusions to be drawn in terms of period-specific settlement activity and for new insights to be gained into the way settlement patterns have changed in the area over several thousand years. Background The archaeological potential of the study area was considered to be low until recently, probably because of its desolate and thinly settled nature during recent and historical times, as this description of the parish of Herne, in the eastern part of the coastal levels, makes clear: This parish is situated about six miles north-eastwards from Canterbury, in 189 TIM ALLEN Map. -

ALFRED NYE & SON, 17. St. Margaret's Street

20 CANTERBURY, HERNE BAY, WHITSTABLE --------------------------------- ---------~·---------------------- Mdfaster, John, Esq. (J.P.) The Holt, .:\Iount, H. G. Esq. (Roselands) Whit Harbledown stable road l\IcQueen, Mrs. (R-ae Rose) Clover rise, Mourilyan, Staff-Corn. T. Longley Whitstable (R.N., J.P.) 5 St. Lawrence Yils. Meakin, Capt. G. (The Shrubbery) Old Dover road Barham 1\Iourilyan, The Misses, 3 St. Lawrence ;\[,ll·w;·, Rev. F. H. (::\LA.) (The Rec villas, Old Dover road tory) Barham 1\luench, Bernard, Esq. (Glen Rest) \'Ie~senger, Robert, Esq. (A. R.I.B.A.) Salisbury road, Herne Bay (The Hut) Hillborough rd. Ilerne ~Ioxon, Capt. Cha:rles Ash (Cedar Bay (Herne Bay Club) Towers) Tankerton rd. W'stable 1\Ietcalfe, Engineer-Capt. Henry Wray 1\Iunn, l\Irs. 33 St. Augustines road (The Clave1ings) Harbledown l\Iurgatroyd, l\Irs. J. (Kable Cot) Mills, Mrs. 4 Ethelbert road Tankerton road, Whitstable Miles, Francis, Esq. Glendhu, Ed- Murphy, Capt. C. E. (F.R.C.S.) dington . (Fordwich House) Fordwich MiLler, J. C. Esq. (M.A.) (Seasa1ter l\Iurrell, Rev. Frederick John (Wesley Lodge) Seasalter Cross, Whit Manse) Whitstable road stable Milner, The Right Hon. Viscount Neilson, Lieut. \V. 27 Old Dover road (G.C.B., G.C.M.G., etc.) Sturry N elsvn, Sidney Herbert, Esq. Barton Court, Sturry; and 17 Great Col- , Mill House, Barton lege Street, S.W. (Clubs: Brook's,! Neville, F. W. Esq. (Elm Croft) Clap Athenaeum, and New University) 1 ham hill, Whitstable 1\Iitchell, Lady (Burgate House) 11 Nt:Vi.lle, J. J. Esq. (Homeland) Clap Burgate street ham hill, Whitstable N c' ille, The lVIisses (Amyand) Clap 1Vluw:y, 1\lrs. -

Community Network Profile Herne

Community network profile Herne Bay November 2015 Produced by Faiza Khan: Public Health Consultant ([email protected]) Wendy Jeffries: Public Health Specialist ([email protected]) Del Herridge, Zara Cuccu, Emily Silcock: Kent Public Health Observatory ([email protected]) Last Updated: 9th June 2016 | Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................ 5 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Key Findings ................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction & Objectives....................................................... 9 2.1 Community Network Area .......................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Community Network ....................................................................................................... 9 3. Maternity ............................................................................. 10 3.1 Life expectancy at birth ............................................................................................. 10 3.1.1 Community network life expectancy trend .................................................................. 10 3.1.2 Ward level life expectancy ............................................................................................ 11 3.2 General fertility rate ................................................................................................. -

D'elboux Manuscripts

D’Elboux Manuscripts © B J White, December 2001 Indexed Abstracts page 63 of 156 774. Halsted (59-5-r2c10) • Joseph ASHE of Twickenham, in 1660 • arms. HARRIS under Bradbourne, Sevenoaks • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 =, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE 775. Halsted (59-5-r2c11) • Thomas BOURCHIER of Canterbury & Halstead, d1486 • Thomas BOURCHIER the younger, kinsman of Thomas • William PETLEY of Halstead, d1528, 2s. Richard = Alyce BOURCHIER, descendant of Thomas BOURCHIER the younger • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761 776. Halsted (59-5-r2c12) • William WINDHAM of Fellbrigge in Norfolk, m1669 (London licence) = Katherine A, d. Joseph ASHE 777. Halsted (59-5-r3c03) • Thomas HOLT of London, d1761, s. Thomas HOLT otp • arms. HOLT of Lancashire • John SARGENT of Halstead Place, d1791 = Rosamund, d1792 • arms. SARGENT of Gloucestershire or Staffordshire, CHAMBER • MAN family of Halstead Place • Henry Stae MAN, d1848 = Caroline Louisa, d1878, d. E FOWLE of Crabtree in Kent • George Arnold ARNOLD = Mary Ann, z1760, d1858 • arms. ROSSCARROCK of Cornwall • John ATKINS = Sarah, d1802 • arms. ADAMS 778. Halsted (59-5-r3c04) • James ASHE of Twickenham, d1733 = ……, d. Edmund BOWYER of Richmond Park • Joseph WINDHAM = ……, od. James ASHE • George Arnold ARNOLD, d1805 • James CAZALET, d1855 = Marianne, d1859, d. George Arnold ARNOLD 779. Ham (57-4-r1c06) • Edward BUNCE otp, z1684, d1750 = Anne, z1701, d1749 • Anne & Jane, ch. Edward & Anne BUNCE • Margaret BUNCE otp, z1691, d1728 • Thomas BUNCE otp, z1651, d1716 = Mary, z1660, d1726 • Thomas FAGG, z1683, d1748 = Lydia • Lydia, z1735, d1737, d. Thomas & Lydia FAGG 780. Ham (57-4-r1c07) • Thomas TURNER • Nicholas CARTER in 1759 781. -

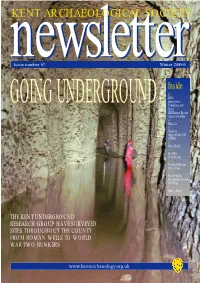

K E N T a Rc H a E O Lo G I C a L S O C I E

KE N T ARC H A E O LO G I C A L SO C I E T Y nnIssue numberee 67 wwss ll ee tt tt ee Winter r2005/6r Inside 2-3 KURG Library Notes GOING UNDERGROUND Tebbutt Research Grants KHBCRequire Recruits Letters to the Editor 4-5 What’s on 6-7 What’s on Happy Birthday CAT CATKITS 8-9 Notice Board 10-11 Bee Boles Cattle Droving 12-13 Wye Rural Museum YACActivities 14-15 Thanet Pipeline Microfilm Med Records New Books 16 Hunt the Saxons THE KENT UNDERGROUND RESEARCH GROUP HAVE SURVEYED SITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTY FROM ROMAN WELLS TO WORLD WAR TWO BUNKERS www.kentarchaeology.org.uk KE N T UN D E R G R O U N D RE S E A R C H GR O U P URG is an affiliated group of the KAS. We are mining historians – a unique blend of unlikely Kopposites. We are primarily archaeologists and carry out academic research into the history of underground features and associated industries. To do this, however, we must be practical and thus have the expertise to carry out exploration and sur- veying of disused mines. Such places are often more dangerous than natural caverns, but our members have many years experience of such exploration. Unlike other mining areas, the South East has few readily available records of the mines. Such records as do exist are often found in the most unlikely places and the tracing of archival sources is an ongoing operation. A record of mining sites is maintained and constantly updated as further sites are discovered. -

Community PRIDE

EVENTS AT CANTERBURY CHRIST CHURCH UNIVERSITY 2018 SUMMER 2018 CHRIST CHURCH PROUD TO SUPPORT Community PRIDE MARITIME KENT IN THE SNOW: Summer / THROUGH THE AGES STEPHANIE QUAYLE matters Friday 22 June, 7pm and Saturday 11 August to Canterbury Christ Church Saturday 23 June, 5pm Saturday 22 September University was proud to be one of A regular update from Canterbury Christ Church Old Sessions House, Sidney Cooper Gallery, the sponsors for this year’s Pride University for local residents Longport, CT1 1PL 22-23 St Peter’s Street, Canterbury festival, a celebration This lecture on Kent’s rich marine Canterbury CT1 2BQ of the LGBT+ community. environment and changes to the Artist Stephanie Quayle will consider coastline over the years, features the legacy of the gallery’s namesake The event, which took place on Richard Holdsworth MBE (Chatham and founder, Thomas Sidney Cooper – Saturday 9 June, attracted thousands UNIVERSITIES Historic Dockyard) on Friday a renowned livestock painter. of people who came together in evening (7pm). the city centre to join in the carnival RECEIVE FUNDING Saturday’s educational session is atmosphere. TO DEVELOP KENT brought to you by Christ Church’s Dr MOTION ALPHA SUMMER The event began with a parade Moving out Chris Young. PROJECT: ONE WEEK AND MEDWAY’S DANCING COURSE through Canterbury High Street, Tickets cost £18 per person, £16 Kent featuring local organisations at the end of the academic year FIRST MEDICAL Archaeological Society members and Monday 20 August to and groups, followed by live £10 for Christ Church students. Friday 24 August, 10am to 4pm SCHOOL entertainment in the Dane John The universities, working with Canterbury City Council, are here to help Anselm Studio 2, North Holmes Gardens, as well as food and drink Road, Canterbury Campus, CT1 1QU students and local communities plan ahead for the end of the academic DATES stalls, and a Pride marketplace. -

THE KENT COUNTY COUNCIL (CANTERBURY RURAL PARISHES) (TRAFFIC REGULATION and STREET PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT No 3) ORDER 2002

THE KENT COUNTY COUNCIL (CANTERBURY RURAL PARISHES) (TRAFFIC REGULATION AND STREET PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT No 3) ORDER 2002 Notice is hereby given that KENT COUNTY COUNCIL propose to make the above named Order, under sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3), 3(2), 4(1) and 4(2), 32(1), 35(1), 45, 46, 49 and 53 of the road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, and of all other enabling powers, and after consultation with the chief officer of police in accordance with Paragraph 20 of Schedule 9 to the Act: The effect of the Order will be to introduce changes to waiting restrictions, parking places and formalise disabled drivers parking bays on the following roads or lengths of roads: - - SWEECHGATE - BROAD OAK CHURCH ROAD - LITTLEBOURNE STATION ROAD - CHARTHAM -- CHAFY CRESCENT - STURRY THE GREEN - CHARTHAM MILL ROAD - STURRY -:- FAULKNERS LANE - HARBLEDOWN --ASHENDEN CLOSE - THANINGTON - FORDWICH ROAD - FORDWICH WITHOUT MARLOW MEADOWS - FORDWICH --- STRANGERS CLOSE - THANINGTON THE MALTINGS - LITTLEBOURNE WITHOUT JUBILEE ROAD - LITTLEBOURNE STRANGERS LANE - THANINGTON HIGH STREET - LITTLEBOURNE WITHOUT Full details are contained in the draft Order which together with the relevant plans, any Orders, amended by the proposals and a statement of reasons for proposing to make the Order may be examined on Mondays to Fridays at the Council Offices, Military Road, Canterbury Between 8.30am and 5pm and in Sturry Library during normal opening hours. If you wish to offer support for or object to the proposed Order you should send the grounds in writing to the Highway Manager, Council Offices, Military Road, Canterbury, CT1 1YW by noon on Tuesday 7 May 2002. -

Investing in the Student Buy-To-Let Market

Investing In the Student Buy-to-let Market By Ajay Ahuja Visit: WWW.AJAYAHUJA.CO.UK 1 ABOUT THE RESEARCHER Having spent much of my time providing the business scope, I must state that I am indebted to the research input offered by a colleague. I would like to thank the immeasurable efforts of Kashim Uddin, whose hard work and persistence has seen the project through from start to finish. Having recently completed a research-based Masters degree in the sciences, his well- nourished analytical skills and versatile creative input has been of huge importance in the delivery of this book. Still in his infancy of business appreciation, his enthusiasm for this book has been more than welcoming and we’ll hopefully see some more of his work in the near future. Introduction The government intends to have 50% of 18-30 year olds in higher education by the year 2010. With the Buy-to-Let market seemingly over saturated, a steady and buoyant student buy-to-let market is one that still offers the potential of good returns. There are multiple reasons as to why the student buy-to-let is a worthwhile investment. UCAS, the University applications agency, has seen a year-by- year increase in applications. The Increased student numbers are fuelling a rush to build. It is a well-known fact that in today’s competitive market, universities are struggling financially, which is having knock-on effects. In addition to the increased numbers of students, massive student housing shortage and lack of Visit: WWW.AJAYAHUJA.CO.UK 2 investment in new housing initiatives offered by the universities, the benefits of private investment has never been better. -

Tenterden Royal Visits and Other Events

Tenterden Royal Visits and Other Events Death of Queen Victoria Queen Victoria, whose reign had dominated much of the last century passed away on Monday 22 January 1901and the following Sunday all places of worship in the town special reference was made of her late majesty and the Dead March (a funeral march) was played at each service. The funeral of the Queen took place on Saturday 3 February 2001 and the day was observed with every sign of mourning in the Borough, business being suspended for the day. A memorial service, which was attended by the Mayor and members of the Corporation in state, was held in the parish church at two o’clock. In a crowded church, the vicar (Rev S C Lepard) and his son (Rev A G G Lepard) carried out a most impressive service. The organist (Mr A H Smith) played the “Dead March” at the commencement of the service. At three o’clock a service, conducted by Mr R Weeks, was held in the Town Hall, which was filled to overflowing. Proclamation of King Edward VII (Kentish Express, February 2, 1901) At Tenterden the ceremony was carried out according to ancient custom on Monday. At noon the Mayor (Ald Hardcastle) in his robes and chain of office, attended by his Sergeants at Mace in their quaint dress, and accompanied by the Aldermen and members of the Council, the Town Clerk and Clerk of the Peace, assembled in front of the Town Hall, and, at the command of the Mayor the proclamation was read by the Town Clerk (Mr J Munn Mace), at the conclusion of which the band of the G Company, 2nd Volunteer Battalion, East Kent Regiment played “God Save the King”.