Study Guide for the Midterm Exam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hassuna Samarra Halaf

arch 1600. archaeologies of the near east joukowsky institute for archaeology and the ancient world spring 2008 Emerging social complexities in Mesopotamia: the Chalcolithic in the Near East. February 20, 2008 Neolithic in the Near East: early sites of socialization “neolithic revolution”: domestication of wheat, barley, sheep, goat: early settled communities (ca 10,000 to 6000 BC) Mudding the world: Clay, mud and the technologies of everyday life in the prehistoric Near East • Pottery: associated with settled life: storage, serving, prestige pots, decorated and undecorated. • Figurines: objects of everyday, magical and cultic use. Ubiquitous for prehistoric societies especially. In clay and in stone. • Mud-brick as architectural material: Leads to more structured architectural constructions, perhaps more rectilinear spaces. • Tokens, hallow clay balls, tablets and early writing technologies: related to development o trade, tools of urban administration, increasing social complexity. • Architectural models: whose function is not quite obvious to us. Maybe apotropaic, maybe for sale purposes? “All objects of pottery… figments of potter’s will, fictions of his memory and imagination.” J. L. Myres 1923, quoted in Wengrow 1998: 783. What is culture in “culture history” (1920s-1960s) ? Archaeological culture = a bounded and binding ethnic/cultural unit within a defined geography and temporal/spatial “horizons”, uniformly and unambigously represented in the material culture, manifested by artifactual assemblage. pots=people? • “Do cultures actually -

AN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN CASE STUDY a Primary

54 RETHINKINGCERAMIC DEGENERATION: AN ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIAN CASE STUDY Steven E. A primary researchconcern of archaeologists is the explanation of social change. Since archaeologists must deal with changeas itis mani- fested in the variability of material culture, itis not surprising that special attention has been givento studies of pottery, one of the most abundant forms of archaeological evidence,and onemost sensitive to tem- poral change. Unfortunately, interpretations of changingpottery reper- toires have usually failed to consider thesocioeconomic factors which also may be responsible for ceramic variation. This has been notably true when trends of change are judged to be Hdegenerative.htA study of ceramic change in the 'IJbaid and Uruk periods ofMesopotamia illustrates how can be correlated with the development of complex societies in the region. An Introduction to the Problem of Degeneration A heterodox approach to the explanation ofspecific Mesopotamian instances of supposed ceramic degenerationis-proposed in this paper for three fundamental reasons. First, traditional approaches all too often do not explain this form of change. At best they describe it and at worst, merely label it. Second, traditional approaches failto view changing material culture in light ofgreater economic frameworks which restrict behavior in all complex societies, includingour own. Third, traditional notions of degenerationare rarely explicitly defined, and tend to focus on examples of declining elegancein painted decoration to the exclusion of other aspects of ceramic change (cf.,Perkins 191+9:75). hDegeneration,hlas presently ill—defined, simply is not productive for the study of social change (cf., Lloyd 1978:45). Further,existing archaeological accounts of degenerationcommonly make the error of dealing with the resultsof change while overlooking the underlying basis of change: altered patterns of human behavior. -

(Main Building) Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 Munich

11th ICAANE Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich Hauptgebäude (main building) Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 Munich Time 03.04.2018 8:30 onwards Registration (Hauptgebäude of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich) Welcome 10:00 - 10:45 Bernd Huber (President of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität/LMU Munich) Paolo Matthiae (Head of the International ICAANE Comittee) Adelheid Otto (Head of the Organizing Comittee) 10:45 - 11:15 Key note: Shaping the Living Space Ian Hodder 11:15 - 11:45 Coffee 11:45 - 12:15 Key note: Mobility in the Ancient Near East Roger Matthews 12:15 - 12:45 Key note: Images in Context Ursula Calmeyer-Seidl 12:45 - 14:00 Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Lunch Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Section 4 Section 7 Section 7 Section 7 Images in Context Archaeology as Engendering Near Mobility in the Cultural Heritage Eastern Field reports Field reports Field reports Ancient Near Archaeology East I II III 14:00 - 14:30 Arkadiusz Vittoria Karen Sonik Cinzia Pappi and Jebrael Nokandeh Flemming Højlund Marciniak Dall'Armellina Minor and Marginal? Constanza and Mahdi Jahed The collapse of the Mobility of people Images of a new Model and Coppini Rescue Archaeology Dilmun Kingdom and and ideas in the Aristocracy. A koinè Transgressive Women From Ahazum to of Nay Tepe, Iran: the Sealand Dynasty Near East in the of symbols and in Mesopotamia's Idu: The Gorgan Plain second half of the cultural values in the Pictorial and Literary Archaeological seventh millennium Caucasus, Anatolia Arts Survey of Koi- BC. The Late and Aegean -

The Ancient Near East

A History of Knowledge Oldest Knowledge What the Jews knew What the Sumerians knew What the Christians knew What the Babylonians knew Tang & Sung China What the Hittites knew What the Japanese knew What the Persians knew What the Muslims knew What the Egyptians knew The Middle Ages What the Indians knew Ming & Manchu China What the Chinese knew The Renaissance What the Greeks knew The Industrial Age What the Phoenicians knew The Victorian Age What the Romans knew The Modern World What the Barbarians knew 1 What the NearEast knew Piero Scaruffi 2004 2 What the Near-East knew • Bibliography – Henry Hodges: Technology in the Ancient World (1970) – Arthur Cotterell: Penguin Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations (1980) – Michael Roaf: Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East (1990) – Hans Nissen: The Early History of the Ancient Near East (1988) – Annie Caubet: The Ancient Near East (1997) – Alberto Siliotti: The Dwellings of Eternity (2000) – Trevor Bryce: The kingdom of the Hittites (1998) – Bernard Lewis: Race and Slavery in the Middle East3 (1992) Ancient Civilizations • River valleys 4 Ancient Civilizations • River valleys – Water means: • drinks, • fishing/agriculture/livestock (food), • transportation • energy 5 The Ancient Near East 6 http://victorian.fortunecity.com/kensington/207/mideast.html Ancient Near East • The evolution of knowledge – End of the ice age – Climatic changes – Hunters follow game that moves to new areas (e.g., northern Europe) – Others turn to farming and hunting new game (cattle, sheep) – Technology (“what farmers -

The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia

Athens Journal of History - Volume 6, Issue 1, January 2020 – Pages 73-96 The Appearance of Bricks in Ancient Mesopotamia By Kadim Hasson Hnaihen Mesopotamia is a region in the Middle East, situated in a basin between two big rivers- the Tigris and the Euphrates. About 5,500 years ago, much earlier than in Egypt, ancient civilization began, one of the oldest in the world. Continuous development was an important factor of everyday life. A warm climate, fertile soil, mixed with the sediment of flowing rivers and perhaps even the first oak all. A deficit of stone for building shelter was an impediment that the Sumerians faced, but from this shortage they found the perfect solution for their construction-brick. Shelter, homes and other buildings were built from material available in the area, such as clay, cane, soil, mule. Sumerians mastered the art of civic construction perfectly. They raised great buildings, made of bricks (Ziggurats, temples, and palaces) richly decorated with sculptures and mosaics. In this article I will focus on the most interesting time period in my opinion- when brick appeared, I will comment upon the process of production and the types of the brick used in Mesopotamia. It should be noted that the form we know today has been shaped by the cultural and social influences of many peoples who have successively settled these lands, continuing to a large extent the cultural heritage of the former. Introduction The ancient population of Iraq (from the Stone Age, 150,000 BC to 8,000 BC) inhabiting Mesopotamia is one of the oldest civilizations to be discovered. -

Eridu, Dunnu, and Babel: a Study in Comparative Mythology

ERIDU, DUNNU, AND BABEL: A STUDY IN COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY by PATRICK D. MILLER, JR. Princeton Theological Seminary, Princeton, NJ 08542 This essay focuses on some themes in two quite different myths from ancient Mesopotamia, one known commonly as the Sumerian Deluge or Flood story, discovered at Nippur and published around the turn of the century by Poebel (I 9 I 4a and b ), the other published much more recently by Lambert and Walcot (1966) and dubbed by Jacobsen (1984) "The Harab Myth." The former myth was the subject of some attention at the time of its publication and extensive analysis by Poebel, par ticularly in King's Schweich Lectures (1918). As Jacobsen notes, it has not been the subject of much further work except for Kramer's transla tion (Pritchard, 1955, pp. 42-44) and Civil's translation and notes in Lambert and Millard (1969, pp. 138-147). More recently, Kramer has given a new translation of the text together with notes (Kramer, 1983). Both texts have now been the subject of major new treatments in the last three or four years by Jacobsen (1978 and 1984), and that is in a large sense the impetus for my turning to them. Indeed, I first became interested in the two texts when Jacobsen delivered a paper on them entitled "Two Mesopotamian Myths of Beginnings" at a symposium on mythology given at Sweetbriar College several years ago. His rationale for dealing with the two of them at that time was that each "in its own way stands apart and it seems to me, raises interesting questions of a more general nature-about composition, interpretation, and what hap pens when a myth is borrowed from one people to another" ( 1978, p. -

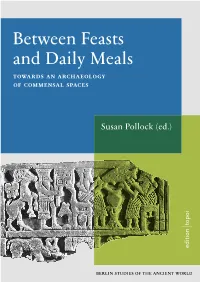

Between Feasts and Daily Meals. Towards an Archaeology Of

Between Feasts and Daily Meals Susan Pollock (ed.) BERLIN STUDIES OF THE ANCIENT WORLD – together in a common physical and social setting – is a central element in people’s everyday lives. This makes com- mensality a particularly important theme within which to explore social relations, social reproduction and the working of politics whether in the present or the past. Archaeological attention has been focused primarily on feasting and other special commensal occasions to the neglect of daily commensality. This volume seeks to redress this imbalance by emphasizing the dynamic relation between feasts and quotidian meals and devoting explicit attention to the micro- politics of Alltag (“the everyday”) rather than solely to special occasions. Case studies drawing on archaeological ( material) as well as written sources range from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in Western Asia and Greece, Formative to late pre-Columbian com munities in Andean South America, and modern Europe. berlin studies of 30 the ancient world berlin studies of the ancient world · 30 edited by topoi excellence cluster Between Feasts and Daily Meals towards an archaeology of commensal spaces edited by Susan Pollock Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. © 2015 Edition Topoi / Exzellenzcluster Topoi der Freien Universität Berlin und der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Cover image: Wall plaque with feasting scene, found in Nippur. Baghdad, Iraq Museum. Winfried Orthmann, Propyläen Kunstgeschichte Vol. 14: Der alte Orient. Berlin: Propyläen, 1975, Pl. 79b. Typographic concept and cover design: Stephan Fiedler Printed and distributed by PRO BUSINESS digital printing Deutschland GmbH, Berlin ISBN 978-3-9816751-0-8 URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:188-fudocsdocument0000000222142-2 First published 2015 Published under Creative Commons Licence CC BY-NC 3.0 DE. -

Neolithic Period, North-Western Saudi Arabia

NEOLITHIC PERIOD, NORTH-WESTERN SAUDI ARABIA Khalid Fayez AlAsmari PhD UNIVERSITY OF YORK ARCHAEOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2019 Abstract During the past four decades, the Neolithic period in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) had received little academic study, until recently. This was due to the previous widely held belief that the Arabian Peninsula had no sites dating back to this time period, as well as few local researchers and the scarcity of foreign research teams. The decline in this belief over the past years, however, has led to the realisation of the importance of the Neolithic in this geographical part of the world for understanding the development and spread of early farming. As well as gaining a better understanding of the cultural attribution of the Neolithic in KSA, filling the chronological gaps in this historical era in KSA is vital, as it is not well understood compared to many neighbouring areas. To address this gap in knowledge, this thesis aims to consider whether the Northwest region of KSA was an extension of the Neolithic developments in the Levant or an independent culture, through presenting the excavation of the Neolithic site of AlUyaynah. Despite surveys and studies that have been conducted in the KSA, this study is the first of its kind, because the site "AlUyaynah", which is the focus of this dissertation, is the first excavation of a site dating back to the pre-pottery Neolithic (PPN). Therefore, the importance of this study lies in developing an understanding of Neolithic characteristics in the North-Western part of the KSA. Initially, the site was surveyed and then three trenches were excavated to study the remaining levels of occupation. -

The Cradle of Civilization- Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent

The Cradle of Civilization- Mesopotamia and the Fertile Crescent Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Unit Two AB * Cradling Civilization • Mesopotamian Society • Although kings were not viewed as gods, they were considered to be appointed by the gods. • The city's priest, however, still held influence. A priest's disagreement with a king's decision could lead to tension. • For this reason, the king may have appointed members of the royal household to religious official status. • Sargon used religion to display his power. His land expanded through one of southern Mesopotamia's largest cities, Sumer, and also into northern Mesopotamia. • Sargon's successors held control over their land until around 1750 BC, when the land was conquered by Babylonian leader Hammurabi. • Hammurabi is unique because he created a code of laws governing behavior. • The code consisted of over 200 acts and their required punishment. * Cradling Civilization • Mesopotamian Society • Hammurabi claimed authority to create these laws by stating they were dictated to him by Marduk, the patron god of Hammurabi's homeland of Babylon. • The top of the stele where the Code of Hammurabi was inscribed. It depicts the god Marduk (seated) giving the law to Hammurabi * The Ubaid Period • The Ubaid Period was the Middle East’s Neolithic age, in which migrating hunter gatherers settled down into sedentary agricultural life styles. • The focal point of the Ubaid period was in the south of present day Iraq, on what was then the shores of the -

Paper Abstracts

PAPER ABSTRACTS Plenary Address Eric H. Cline (The George Washington University), “Dirt, Digging, Dreams, and Drama: Why Presenting Proper Archaeology to the Public is Crucial for the Future of Our Field” We seem to have forgotten that previous generations of Near Eastern archaeologists knew full well the need to bring their work before the eyes of the general public; think especially of V. Gordon Childe, Sir Leonard Woolley, Gertrude Bell, James Henry Breasted, Yigael Yadin, Dame Kathleen Kenyon, and a whole host of others who lectured widely and wrote prolifically. Breasted even created a movie on the exploits of the Oriental Institute, which debuted at Carnegie Hall and then played around the country in the 1930s. The public was hungry for accurate information back then and is still hungry for it today. And yet, with a few exceptions, we have lost sight of this, sacrificed to the goal of achieving tenure and other perceived institutional norms, and have left it to others to tell our stories for us, not always to our satisfaction. I believe that it is time for us all— not just a few, but as many as possible—to once again begin telling our own stories about our findings and presenting our archaeological work in ways that make it relevant, interesting, and engaging to a broader audience. We need to deliver our findings and our thoughts about the ancient world in a way that will not only attract but excite our audiences. Our livelihoods, and the future of the field, depend upon it, for this is true not only for our lectures and writings for the general public but also in our classrooms. -

The Most Ancient Trace on the Commercial and Civilizational Relations Between

The most ancient trace on the commercial and civilizational relations between Mesopotamia and China By Dr. Bahnam Abu Al-Souf: The ancient Iraqis needed about eight thousand years, a number of raw materials to make their tools and weapons and those materials were not available or they were rare in Mesopotamia. The children and women's needs for the make-up required bringing all kinds of valuable pearls and shells, most of which were not found in various Iraqi areas. With the progress growth of the first agricultural villages in Northern and central Iraq and with their increase in number during the 6th and 5th millennium B.C., and due to the development of the social life in those first villages and the spread of many beliefs and religious practices related to the fertility, land, birth and magic powers of certain symbols and things the Iraqis who inhabited those villages brought kinds of shells from the coast of the Mediterranean sea and the Persian gulf carnelian from the Southern parts of the Arabian peninsula and from the eastern parts of Iran. They also got lapis-lazuli from its mining areas in Badkashan in the Northern Afghanistan. They also brought copper from Oman in the Persian Gulf and gold, silver and copper from Anatolia (1) and cedar woods from the mounta1ns of Lebanon. (2) There were two main roads to bring the materials from Anatolia. The first one came from the center and Southern parts of Asia minor, passing through town in Northern Syria, where it divided into two branches, one of them going southwards towards Palestine and then went westwards to Sinai and Egypt. -

Girda Qala North Trench D: Stratigraphy and Architecture

Girda QALA North TRENCH D: Stratigraphy AND Architecture Clélia Paladre, Rateb al Debs, Adel Hama Amin and Régis Vallet he excavations of Trench D have been carried out during seventeen days, from the 8th Tto the 25th of October 2016. The team was composed of four members, Clélia Paladre, Rateb al Debs, Adel Hama Amin and Régis Vallet plus a team of four workers. The aim of these excavations was to obtain southern Uruk stratified contexts in order to achieve a better understanding of the Uruk presence in the Qara Dagh area. We decided to open a trench of 10 x 5 m in the northern slope of the mound, oriented more or less north-west south-east. The emplacement of the trench was based on the results of the geomagnetic and archaeologi- cal surveys. Indeed, during the surface survey, we were able to observe a high concentration of southern Uruk material (ceramics -and animal bones) in the centre of the zone III (the richer zone of the prospection, cf. supra). This high concentration was associated on the geomagne- tic plan with an imposing anomaly (Fig. 1). These excavations allowed us to recognize five successive levels of occupation, all of them dating back from the Middle Uruk period1 (Fig. 2 and 3). Fig. 1 - Plan of Girdi Qala North Mound with the location of the presumed Uruk site, Trench D and the results of the geomagnetic survey. 1. See the pottery study, Baldi, infra. 98 Girda Qala North Mound Trench D: Stratigraphy and Architecture Fig. 2 - General plan of the Trench D.