Avian Flight Originated in Arboreal Archosaurs Gliding On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flying Dromaeosaurs

A winged, but flightless, Deinonychus by Stephen A. Czerkas FLYING DROMAEOSAURS Stephen A. Czerkas, Dianshuang Zhang, Jinglu Li and Yinxian Li The Dinosaur Museum, 754 South 200 West, Blanding, Utah 84511, USA; Liaoning Provincial Bureau of Land Resources Management, Liaoning Fossil Administration Office, and Liaoning Museum of Paleontology, Left of Nanshan Park, Beipiao, Liaoning Province 122100, People’s Republic of China. The Dinosaur Museum © 2002 Abstract Dromaeosaurs have been regarded as theropod dinosaurs that were among the closest avian ancestors which were strictly terrestrial having not yet evolved the ability to fly. Consequently, phylogenetic analyses have resulted in the claims of birds having evolved from “the ground up” within a dinosaurian ancestry. Though widely accepted, the relationship between birds and dinosaurs has remained highly controversial and disputed by advocates of birds as having been derived from an arboreal, non-dinosaurian type of archosaur. The cladistical interpretation of the dinosaur/bird relationship hinges upon the presumption of the dromaeosaurs inability to fly. Recent discoveries of dromaeosaurs have revealed impressions of feathers and avian characters in the skeleton that nearly equal and even surpass that of Archaeopteryx. Yet despite this, the ability to fly has been discounted due to the shorter length of the forelimbs. Described below are two such dromaeosaurs, but preserved with impressions of primary flight feathers extending from the manus which demonstrate an undeniable correlation towards the ability to fly. This compelling evidence refutes the popular interpretation of birds evolving from dinosaurs by revealing that dromaeosaurs were already birds and not the non-avian theropod dinosaurs as previously believed. -

A Chinese Archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx Gen. Nov

A Chinese archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. by Qiang Ji and Shu’an Ji Geological Science and Technology (Di Zhi Ke Ji) Volume 238 1997 pp. 38-41 Translated By Will Downs Bilby Research Center Northern Arizona University January, 2001 Introduction* The discoveries of Confuciusornis (Hou and Zhou, 1995; Hou et al, 1995) and Sinornis (Ji and Ji, 1996) have profoundly stimulated ornithologists’ interest globally in the Beipiao region of western Liaoning Province. They have also regenerated optimism toward solving questions of avian origins. In December 1996, the Chinese Geological Museum collected a primitive bird specimen at Beipiao that is comparable to Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer, 1992). The specimen was excavated from a marl 5.5 m above the sediments that produce Sinornithosaurus and 8-9 m below the sediments that produce Confuciusornis. This is the first documentation of an archaeopterygian outside Germany. As a result, this discovery not only establishes western Liaoning Province as a center of avian origins and evolution, it provides conclusive evidence for the theory that avian evolution occurred in four phases. Specimen description Class Aves Linnaeus, 1758 Subclass Sauriurae Haeckel, 1866 Order Archaeopterygiformes Furbringer, 1888 Family Archaeopterygidae Huxley, 1872 Genus Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. Genus etymology: Acknowledges that the specimen possesses characters more primitive than those of Archaeopteryx. Diagnosis: A primitive archaeopterygian with claviform and unserrated dentition. Sternum is thin and flat, tail is long, and forelimb resembles Archaeopteryx in morphology with three talons, the second of which is enlarged. Ilium is large and elongated, pubes are robust and distally fused, hind limb is long and robust with digit I reduced and dorsally migrated to lie in opposition to digit III and forming a grasping apparatus. -

LETTER Doi:10.1038/Nature14423

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature14423 A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran theropod with preserved evidence of membranous wings Xing Xu1,2*, Xiaoting Zheng1,3*, Corwin Sullivan2, Xiaoli Wang1, Lida Xing4, Yan Wang1, Xiaomei Zhang3, Jingmai K. O’Connor2, Fucheng Zhang2 & Yanhong Pan5 The wings of birds and their closest theropod relatives share a ratios are 1.16 and 1.08, respectively, compared to 0.96 and 0.78 in uniform fundamental architecture, with pinnate flight feathers Epidendrosaurus and 0.79 and 0.66 in Epidexipteryx), an extremely as the key component1–3. Here we report a new scansoriopterygid short humeral deltopectoral crest, and a long rod-like bone articu- theropod, Yi qi gen. et sp. nov., based on a new specimen from the lating with the wrist. Middle–Upper Jurassic period Tiaojishan Formation of Hebei Key osteological features are as follows. STM 31-2 (Fig. 1) is inferred Province, China4. Yi is nested phylogenetically among winged ther- to be an adult on the basis of the closed neurocentral sutures of the opods but has large stiff filamentous feathers of an unusual type on visible vertebrae, although this is not a universal criterion for maturity both the forelimb and hindlimb. However, the filamentous feath- across archosaurian taxa12. Its body mass is estimated to be approxi- ers of Yi resemble pinnate feathers in bearing morphologically mately 380 g, using an empirical equation13. diverse melanosomes5. Most surprisingly, Yi has a long rod-like The skull and mandible are similar to those of other scansoriopter- bone extending from each wrist, and patches of membranous tissue ygids, and to a lesser degree to those of oviraptorosaurs and some basal preserved between the rod-like bones and the manual digits. -

The Dinosaurs Are Back!

EXHIBITION FOR HIRE THE DINOSAURS ARE BACK! THE DINOSAURS ARE BACK! In partnership with Emilio’s Creations, Universeum proudly presents the unique dinosaur exhibition “The dinosaurs are back”. The latest scientific discoveries are summarised in a spectacular visitor experience with 16 life-size dinosaurs that move and make noises. Ten of them are feathered in accordance with recent research. The exhibition for hire comprises eight different species set in a prehistoric forest landscape with trees and plants from that specific era. Included is the world’s largest known land predator, theSpinosaurus , at 14 metres long and five metres tall. Also on display are the four-metre tall and fully feathered Therizinosaurus and the legendary Tyrannosaurus rex, together with a feathered juvenile. Feathers The dinosaurs in the exhibition for hire The dinosaurs never really died out. They live The dinosaurs in the exhibition have been carefully on and we see and hear them every day. After selected to show a diverse range of species and all, birds are directly descended from some of highlight scientifically interesting points. the most ferocious and predatory dinosaurs, Sinosauropteryx (x2). The first genus of dinosaur discovered with recent research confirming the close outside of Avialae(birds) that is known to have been links between dinosaurs and birds. This feathered. point is clearly illustrated when visitors see the Tyrannosaurus rex (x2). As well as being famous, it is of great feathered dinosaurs in the exhibition. scientific interest. Researchers are speculating as to whether the adult lost the coat of feathers it had when young or Environment whether it retained all or part of it throughout its life. -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

Winter Bird Feeding

BirdNotes 1 Winter Bird Feeding birds at feeders in winter If you feed birds, you’re in good company. Birding is one of North America’s favorite pastimes. A 2006 report from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimates that about 55.5 mil- lion Americans provide food for wild birds. Chickadees Titmice Cardinals Sparrows Wood- Orioles Pigeons Nuthatches Finches Grosbeaks Blackbirds Jays peckers Tanagers Doves Sunflower ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Safflower ◆ ◆ ◆ Corn ◆ ◆ ◆ Millet ◆ ◆ ◆ Milo ◆ ◆ Nyjer ◆ Suet ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ ◆ Preferred ◆ Readily Eaten Wintertime—and the Living’s counting birds at their feeders during selecting the best foods daunting. To Not Easy this winterlong survey. Great Back- attract a diversity of birds, provide a yard Bird Count participants provide variety of food types. But that doesn’t n much of North America, winter valuable data with a much shorter mean you need to purchase one of ev- Iis a difficult time for birds. Days time commitment—as little as fifteen erything on the shelf. are often windy and cold; nights are minutes in mid-February! long and even colder. Lush vegeta- Which Seed Types tion has withered or been consumed, Types of Bird Food Should I Provide? and most insects have died or become uring spring and summer, most dormant. Finding food can be espe- lack-oil sunflower seeds attract songbirds eat insects and spi- cially challenging for birds after a D Bthe greatest number of species. ders, which are highly nutritious, heavy snowfall. These seeds have a high meat-to- abundant, and for the most part, eas- shell ratio, they are nutritious and Setting up a backyard feeder makes ily captured. -

R~;: PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL

....----------- 'r~;: i ! 'r; Pa/eont .. 62(4), 1988, pp. 64~52 Copyright © 1988, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/88/0062-0640$03.00 PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL, CLIMATOLOGICAL, GEOPHYSICAL, SURVIVAL, AND EVOLUTIONARY IMPLICATIONS OF CRETACEOUS POLAR DINOSAURS GREGORY S. PAUL 3109 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 ABSTRACTT- he presence of Late Cretaceous social dinosaurs in polar regions confronted them with winter conditions of extended dark, coolness, breezes, and precipitation that could best be coped with via an endothermic homeothermic physiology of at least the tenrec level. This is true whether the dinosaurs stayed year round in the polar regime-which in North America extended from Alaska south to Montana-or if they migrated away from polar winters. More reptilian physiologies fail to meet the demands of such winters -in certain key ways, a· point tentatively confirmed by the apparent failure of giant Late Cretaceous phobosuchid crocodilians to dwell north of Montana. Low metabolisms were also insufficient for extended annual migrations away from and towards the poles. It is shown that even high metabolic rate dinosaurs probably remained in their polar habitats year-round. The possibility that dinosaurs had avian-mammalian metabolic systems, and may have borne insulation at least seasonally, severely limits their use as polar paleoclimatic and Earth axial tilt indicators. Polar dinosaurs may have been a center of dinosaur evolution. The possible ability of polar dinosaurs to cope with conditions of cool and dark challenges theories that a gradual temperature decline, or a sudden, meteoritic or volcanic induced collapse in temperature and sunlight, destroyed the dinosaurs. INTRODUCTION America suggests that dinosaurs were regularly crossing, and NCREASINGNUMBERSof remains show that dinosaurs lived living upon, the Bering Land Bridge within a few degrees of the I near the North and South Poles during the Cretaceous. -

State of the Palaeoart

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org State of the Palaeoart Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway The discipline of palaeoart, a branch of natural history art dedicated to the recon- struction of extinct life, is an established and important component of palaeontological science and outreach. For more than 200 years, palaeoartistry has worked closely with palaeontological science and has always been integral to the enduring popularity of prehistoric animals with the public. Indeed, the perceived value or success of such products as popular books, movies, documentaries, and museum installations can often be linked to the quality and panache of its palaeoart more than anything else. For all its significance, the palaeoart industry ment part of this dialogue in the published is often poorly treated by the academic, media and literature, in turn bringing the issues concerned to educational industries associated with it. Many wider attention. We argue that palaeoartistry is standard practises associated with palaeoart pro- both scientifically and culturally significant, and that duction are ethically and legally problematic, stifle improved working practises are required by those its scientific and cultural growth, and have a nega- involved in its production. We hope that our views tive impact on the financial viability of its creators. inspire discussion and changes sorely needed to These issues create a climate that obscures the improve the economy, quality and reputation of the many positive contributions made by palaeoartists palaeoart industry and its contributors. to science and education, while promoting and The historic, scientific and economic funding derivative, inaccurate, and sometimes exe- significance of palaeoart crable artwork. -

Evaluating the Ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline Generalist Or Aquatic Pursuit Specialist?

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Evaluating the ecology of Spinosaurus: Shoreline generalist or aquatic pursuit specialist? David W.E. Hone and Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. ABSTRACT The giant theropod Spinosaurus was an unusual animal and highly derived in many ways, and interpretations of its ecology remain controversial. Recent papers have added considerable knowledge of the anatomy of the genus with the discovery of a new and much more complete specimen, but this has also brought new and dramatic interpretations of its ecology as a highly specialised semi-aquatic animal that actively pursued aquatic prey. Here we assess the arguments about the functional morphology of this animal and the available data on its ecology and possible habits in the light of these new finds. We conclude that based on the available data, the degree of adapta- tions for aquatic life are questionable, other interpretations for the tail fin and other fea- tures are supported (e.g., socio-sexual signalling), and the pursuit predation hypothesis for Spinosaurus as a “highly specialized aquatic predator” is not supported. In contrast, a ‘wading’ model for an animal that predominantly fished from shorelines or within shallow waters is not contradicted by any line of evidence and is well supported. Spinosaurus almost certainly fed primarily from the water and may have swum, but there is no evidence that it was a specialised aquatic pursuit predator. David W.E. Hone. Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London, E1 4NS, UK. [email protected] Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742 USA and Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20560 USA. -

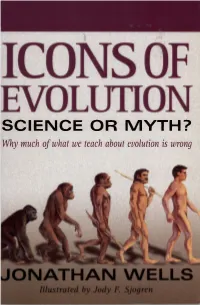

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

A Comparison of Flight Potential Among Small-Bodied Paravians

Chapter 11 High Flyer or High Fashion? A Comparison of Flight Potential among Small-Bodied Paravians T. ALEXANDER DECECCHI,1 HANS C.E. LARSSON,2 MICHAEL PITTMAN,3 AND MICHAEL B. HABIB4 ABSTRACT The origin of flight in birds and its relationship to bird origins itself has achieved something of a renaissance in recent years, driven by the discovery of a suite of small-bodied taxa with large pen- naceous feathers. As some of these specimens date back to the Middle Jurassic and predate the earli- est known birds, understanding how these potential aerofoil surfaces were used is of great importance to answering the question: which came first, the bird or the wing? Here we seek to address this question by directly comparing key members of three of the major clades of paravians: anchiorni- thines, Microraptor and Archaeopteryx across their known size classes to see how they differ in terms of major flight-related parameters (wing loading; disc loading; specific lift; glide speed; takeoff poten- tial). Using specimens with snout to vent length (SVL) ranging from around 150 mm to 400 mm and mass ranging from approximately 130 g to 2 kg, we investigated patterns of inter- and intraspe- cific changes in flight potential. We find that anchiornithines show much higher wing- and disc- loading values and correspondingly high required minimum glide and takeoff speeds, along with lower specific lift and flapping running outputs suggesting little to no flight capability in this clade. In contrast, we see good support for flight potential, either gliding or powered flight, for all size classes of both Microraptor and Archaeopteryx, though there are differing patterns of how this shifts ontogenetically. -

Technical Program

MONDAY, JULY 30 11:00AM 1801770 Polysaccharide Composites as Barrier Materials Jeffrey Catchmark, Penn State, University Park, PA TECHNICAL PROGRAM United States (Presenter: Jeffrey Catchmark) (Jeffrey MONDAY, JULY 30 Catchmark, Kai Chi, Snehasish Basu) 9:30AM-12:00PM 11:15AM 1800994 Production and characterization of in situ synthesis of silver nanoparticles into TEMPO-mediated oxi- The purpose of these Sessions is the open exchange of dized bacterial cellulose and their antivibriocidal ac- ideas, therefore, remarks made by a participant or mem- tivity against shrimp pathogens Sivaramasamy Elayaraja, Zhejiang University, ber of the audience cannot be quoted or attributed to ei- Hangzhou, Zhejiang China, People’s Republic of (Pre- ther the individual or the individuals’ company. NO senter: Sivaramasamy Elayaraja) (Sivaramasamy Ela- RECORDING of the participants’ remarks or discussion is yaraja, Liu Gang, Jianhai Xiang, Songming Zhu) 11:30AM 1801330 Design, Development, Evaluation of Gum Arabic permitted. Pictures of any material shown here are not Milling Machine permitted. Eyad Eltigani, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Khar- toum Sudan (Presenter: Eyad Eltigani) (Eyad Mohamed Eltigani Abuzeid, Khalid Elgassim Mohamed Ahmed, In respect for the presenters and the people attending the Hossamaldein Fadoul Brima) conference, ASABE would request that anyone having a 11:45AM 1801112 The Design of Longitudinal - axial cylinder for the combine pager, cell phone, or other electronic device please turn Meng Fanhu, Sandong University Technology, Zibo, them off. If your situation does not allow for these devices Shandong province China, People’s Republic of (Pre- to be turned off, please reseat yourself close to an exit senter: Meng Fanhu) (Meng Fanhu) such that everyone can benefit from the information pre- sented here without disruption.