Hidden Authority, Public Display: Representations of First Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

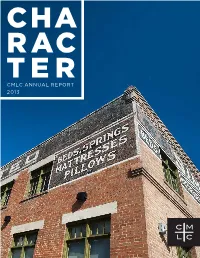

Cmlc Annual Report 2013 Contents

CMLC Annual Report // 2013 CHA1 RAC TER CMLC ANNUAL REPORT 2013 CONTENTS A Message from Lyle Edwards 8 A Message from Michael Brown 10 A Message from Mayor Naheed Nenshi 12 Public Infrastructure Projects 13 Infrastructure Updates 14 Heritage Buildings 16 Ongoing Projects 17 Community Infrastructure Partners 22 Marketing, Public Engagement and Communications 26 Environment and Sustainability 36 Accountability Report 40 Independent Auditor’s Report 49 Financial Statements 51 Notes to Financial Statements 57 CMLC Team 70 CMLC staff showed their true colours true in their unscripted, far-beyond-the-call- of-duty efforts to CHA evacuate, comfort and return home some of RAC the neighbourhood’s TER most vulnerable residents. In a year forever marked by the June 2013 flood event, the residents and developers of East Village showed a strength and generosity that isn’t apparent in everyday life. When the long-standing homes of East Village seniors – Murdoch Manor, King Tower and East Village Place – were compromised by rising waters, CMLC staff showed their true colours in their unscripted, far-beyond-the-call-of-duty participation in efforts to evacuate, comfort and return home some of the neighbourhood’s most vulnerable residents. The infrastructure of East Village proved resilient in 2013 because the flood plain has been raised up to six feet in some places since 2007. But it’s the resiliency and character of the people – residents, business owners, CMLC staff, the East Village Neighbourhood Association and many others – that we remember long after the waters receded. CMLC’s hybrid retail strategy, designed to attract both destination and niche retailers, drew the country’s largest real estate trust and the city’s most enterprising culinary entrepreneurs. -

Calgary's Dynamic Dance Scene P. 15

Enough $$ for YYC music? The Calgary PAGE 19 JOURNALReporting on the people, issues and events that shape our city APRIL 2015 FREE Calgary’s Dynamic Dance Scene P. 15 Trespassing in Medicinal Flying paint elder care homes marijuana A night at Calgary’s only Law being questioned by Calgary’s first medicinal indoor paintball field loved ones of seniors marijuana clinic to open PAGE 4-5 PAGE 6-7 PAGE 28 THIS ISSUE APRIL 2015 FEATURES EDITORS-IN-CHIEF CAITLIN CLOW OLIVIA CONDON CITY EDITORS JOCELYN DOLL JALINE PANKRATZ ARTS EDITORS ALI HARDSTAFF ANUP DHALIWAL CITY FEATURES EDITOR PAUL BROOKS Spring into the SPORTS EDITOR A.J. MIKE SMITH April Journal and come with us to SPORTS PHOTO & PRODUCTION EDITORS some of our MASHA SCHEELE favourite “places.” GABRIELA CASTRO FACULTY EDITORS TERRY FIELD FEATURES PH: (403) 440-6189 [email protected] THE LENS SALLY HANEY PH: (403) 462-9086 [email protected] PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR ADVERTISING BRAD SIMM PH: (403) 440-6946 [email protected] The Calgary Journal reports on the people, issues and events that shape our city. It is produced by journalism students at Mount Royal University. CITY THE LENS PAGE 4 | Trespassing on seniors’ facilities PAGE 16 | Growing dance scene FOLLOW US ONLINE: PAGE 6 | Calgary’s first marijuana clinic @calgaryjournal PAGE 8 | Babyboomers facing homelessness facebook.com/CalgaryJournal ARTS calgaryjournal.ca PAGE 9 | April is poetry month PAGE 20 | Vinyl pressing PAGE 21 | Local bands leaving town for success CONTACT THE JOURNAL: FEATURES PAGE 22 | Funding for artists across Canada -

1979 Year Book

AMERICAN ACADEMY Of ACTUARIES 1979 Year Book PG^,qEMY ti CO 1965 FEBRUARY 1, 1979 When we build, let it be such work as our descen- dants willthank usfor: and let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that the time will come when men will say as they look upon the labor and the substance, "See! this ourfathers didfor us." JOHN RUSKIN AMERICAN ACADEMY Of ACTUARIES 1979 Year Book PUBLISHED BY THE ACADEMY Executive Office Administrative Office 1835 K Street, N.W. 208 South LaSaile Street Washington, D.C. 20006 Chicago, Illinois 60604 FEBRUARY 1, 1979 MADE IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY . BOARD OF DIRECTORS . ACADEMY HEADQUARTERS AND STAFF . STANDING COMMITTEES . SPECIAL COMMIT'TEES . 16 JOINT COMMITTEES . 18 PAST OFFICERS . 20 FUTURE ANNUAL MEETINGS . 22 MEMBERSHIP STATISTICS . 23 IVjEMBERSHIP, FEBRUARY 1, 1979. 25 B3tLAws . 2 67 PRESCRIBED EXAMINATIONS . 277 GUIDES TO PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT . 278 OPINIONS ASTO PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT. 282 FINANCIAL REPORTING RECOMMENDATIONS AND INTERPRETA'IKONS 300 PENSION PLAN RECOMMENDATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS . 350 APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION . 380 DUES . 381 O'I'HER ACTUARIAL ORGANIZATIONS . 382 ACTUARIAL CLUBS . 385 1 HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ACTUARIES It was on October 25, 1965 that the American Academy of Actuaries was organized as an unincorporated association to serve the actuarial profession in the United States. The corresponding national body in Canada, the Canadian Institute of Actuaries, had been incorporated earlier in the same year. For many years the profession in North America had consisted of four bodies: the Casualty Actuarial Society, the Conference of Actuaries in Public Practice, the Fraternal Actuarial Association, and the Society of Actuaries. -

The Calgary Exhibition and Stampedes: Culture, Context and Controversy, 1884-1923

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1999 The Calgary exhibition and stampedes: culture, context and controversy, 1884-1923 English, Linda Christine English, L. C. (1999). The Calgary exhibition and stampedes: culture, context and controversy, 1884-1923 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/17659 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/24998 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Calgary Exhibition and Stampedes: Culture, Context and Controversy, 1884- 1923 Linda Christine English A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA MAY, 1999 Q Linda Christine English 1999 National Library Bibliotheque nationale I*I of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre mlemce Our IW Notre relerence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordi me licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prster, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Mber - Order of the British Empire (Mbe)

MEMBER - ORDER OF THE BRITISH EMPIRE (MBE) MBE 2021 UPDATED: 26 June 2021 To CG: 26 June 2021 PAGES: 99 ========================================================================= Prepared by: Surgeon Captain John Blatherwick, CM, CStJ, OBC, CD, MD, FRCP(C), LLD(Hon) Governor General’s Foot Guards Royal Canadian Air Force / 107 University Squadron / 418 Squadron Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps HMCS Discovery / HMCS York / HMCS Protecteur 12 (Vancouver) Field Ambulance 1 MBE (military) awarded to CANADIAN ARMY WW1 (MBE) CG DATE NAME RANK UNIT DECORATIONS / 09/02/18 AUGER, Albert Raymond Captain Cdn Forestry Corps MBE 12/07/19 BAGOT, Christopher S. Major Cdn Forestry Corps (OBE) MBE 09/02/18 BENTLEY, William Joseph LCol Asst Director Dental Svc MBE 20/07/18 BLACK, Gordon Boyes Major Cdn Forestry Corps MBE 20/07/18 BROWN, George Thomas Lieutenant Cdn Army Medical Corps MBE 12/07/19 CAINE, Martin Surney Lieutenant Alberta Regiment MBE 20/07/18 CALDWELL, Bruce McGregor Major OIC Cdn Postal Corps MBE 09/02/18 CAMPBELL, David Bishop LCol Cdn Forestry Corps MBE 05/07/19 CARLESS, William Edward Lieutenant Canadian Engineers MBE 05/07/19 CASSELS, Hamilton A/Captain Attached RAF MBE 12/07/19 CASTLE, Ivor Captain General List MBE 09/02/18 CHARLTON, Charles Joseph Captain Staff Captain Cdn HQ MBE 12/07/19 CLARKE, Thomas Walter A/Captain Cdn Railway Troops MBE 05/07/19 COLES, Harry Victor Lieutenant Cdn Machine Gun Corps MBE 20/07/18 COLLEY, Thomas Bellasyse Captain Phys & Bayonet Training MBE 09/02/18 COOPER, Herbert Millburn Lieutenant Asst Inspect Munitions MBE 12/07/19 COX, Alexander Lieutenant Saskatchewan Reg MBE 05/07/19 CRAIG, Alexander Meldrum S/Sgt Maj Cdn Army Service Corps MBE 14/12/18 CRAFT, Samuel Louis Captain Quebec Regiment MBE 10/05/19 CRIPPS, George Wilfitt Lieutenant 13 Bn Cdn Railway Troop MBE 12/07/19 CURRIE, Thomas Dickson A/Captain Cdn Railway Troops MBE 12/09/19 CURRY, Charles Townley Hon Lt General List MBE 05/07/19 DEAN, George Edward Lieutenant CFA attched RAF MBE 05/07/19 DRIVER, George Osborne H. -

City-Owned Historic Resource Management Strategy

LAS2014-25 ATTACHMENT 5 HISTORIC BUILDING SNAPSHOTS 1. A.E. Cross House 16. Glenmore Water Treatment Plant 2. Armour Block 17. Grand Trunk Cottage School 3. Bowness Town Hall 18. Hillhurst Cottage School 4. Calgary Public Building 19. Holy Angels School 5. Capitol Hill Cottage School 20. McHugh House 6. Cecil Hotel 21. Merchant’s Bank Building 7. Centennial Planetarium 22. Neilson Block Facade 8. Calgary City Hall 23. North Mount Pleasant School 9. Cliff Bungalow School 24. Reader Rock Garden - Residence 10. Colonel Walker House 25. Rouleau House 11. Eau Claire & Bow River Lumber 26. St.Mary’s Parish Hall/CNR Station 12. Edworthy House 27. Union Cemetery Caretakers Cottage 13. Fire Hall No. 1 28. Union Cemetery Mortuary 14. Fire Hall No. 2 29. Y.W.C.A. 15. Fire Hall No. 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 ISC: UNRESTRICTED Page 1 of 30 LAS2014-25 ATTACHMENT 5 1. A.E. CROSS HOUSE of Calgary's oldest homes and its asymmetrical design features includes several unusual architectural elements typical of the Queen Anne Revival period. These include a wood-shingled hip roof with cross gables, banks of bay windows on the front and side facades, a sandstone foundation, a "widow's walk" balustrade, and gingerbread trim. The interior has many of the original features, including hardwood flooring, fir used for the door and window trim as well as an elaborate open stairway with custom fabricated wood handrails, newels and balusters and two brick fireplaces. -

Glenbow Archives (M-742-7) Harold Mcgill's First World War Letters, January 8-December 6, 1917

Glenbow Archives (M-742-7) Harold McGill's First World War letters, January 8-December 6, 1917 France, Jan 8, 1917. Dear Miss Griffis;- A few minutes ago I was standing in my dugout with my back to the fire thinking very hard things of you, I really was. I was just about to sit down and send you a red hot letter in spite of the chilly atmosphere of the dugout, for it must be nearly a month since you wrote to me previous to your letter just received. As I remarked I was just making your ears burn when an orderly came in with your very nice and flattering letter. Of course we all like a little flattery and yours was so nicely given that I could not feel otherwise that pleased. Many thanks for your congratulations. I am afraid the people at home attach too much importance to these decorations. Sometimes they are awarded to the deserving ones and sometimes ------ . Gen. Byng our corps commander held a battalion inspection the day after Christmas and presented the ribbons to those awarded decorations. Just at present we are in support trenches but it will soon come our turn for the front line again. The weather is atrocious, cold with high wind and rain nearly every day. We had a much better Christmas this season than last. Fortunately we were out of the trenches in reserve and billeted in huts. The weather was fairly well behaved although we had some rain. All the men had a good Christmas dinner including turkey, plum pudding, beer, nuts, candy, etc. -

Native Soldiers – Foreign Battlefields

Remembrance Series Native Soldiers – Foreign Battlefields Cover photo: Recruits from Saskatchewan’s File Hills community pose with elders, family members and a representative from the Department of Indian Affairs before departing for Great Britain during the First World War. (National Archives of Canada (NAC) / PA-66815) Written by Janice Summerby © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Veterans Affairs, 2005. Cat. No. V32-56/2005 ISBN 0-662-68750-7 Printed in Canada Native Soldiers – Foreign Battlefields Generations of Canadians have served our country and the world during times of war, military conflict and peace. Through their courage and sacrifice, these men and women have helped to ensure that we live in freedom and peace, while also fostering freedom and peace around the world. The Canada Remembers Program promotes a greater understanding of these Canadians’ efforts and honours the sacrifices and achievements of those who have served and those who supported our country on the home front. The program engages Canadians through the following elements: national and international ceremonies and events including Veterans’ Week activities, youth learning opportunities, educational and public information materials (including online learning), the maintenance of international and national Government of Canada memorials and cemeteries (including 13 First World War battlefield memorials in France and Belgium), and the provision of funeral and burial services. Canada’s involvement in the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War, and Canada’s efforts during military operations and peace efforts has always been fuelled by a commitment to protect the rights of others and to foster peace and freedom. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

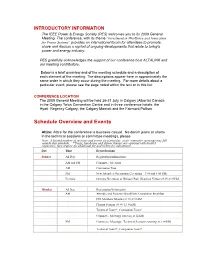

Schedule Overview and Events

INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION The IEEE Power & Energy Society (PES) welcomes you to its 2009 General Meeting. The conference, with its theme “Investment in Workforce and Innovation for Power Systems” provides an international forum for attendees to promote, share and discuss a myriad of ongoing developments that relate to today's power and energy industry. PES gratefully acknowledges the support of our conference host ALTALINK and our meeting contributors. Below is a brief overview and of the meeting schedule and a description of each element of the meeting. The descriptions appear here in approximately the same order in which they occur during the meeting. For more details about a particular event, please see the page noted within the text or in this list: CONFERENCE LOCATION The 2009 General Meeting will be held 26-31 July in Calgary (Alberta) Canada in the Calgary Telus Convention Centre and in three conference hotels: the Hyatt Regency Calgary, the Calgary Marriott and the Fairmont Palliser.. Schedule Overview and Events Attire: Attire for the conference is business casual. No denim jeans or shorts in the technical sessions or committee meetings, please. Note: A limited number of sessions and events (in particular, some committee meeting) may fall outside this schedule. *Tours, luncheons and dinner theater are optional with limited capacities; they require an additional fee and tickets for admittance. Day Time Event/Sessions Sunday All Day Registration/Information AM and PM Committee Meetings AM Companion Tour PM New Attendees Orientation -

A Case Study on Narrative Form and Aboriginal-Government Relations During the Second World War P

Document generated on 09/26/2021 12:20 a.m. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association Revue de la Société historique du Canada The Irony and the Tragedy of Negotiated Space: A Case Study on Narrative Form and Aboriginal-Government Relations during the Second World War P. Whitney Lackenbauer Volume 15, Number 1, 2004 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/012073ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/012073ar See table of contents Publisher(s) The Canadian Historical Association/La Société historique du Canada ISSN 0847-4478 (print) 1712-6274 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Lackenbauer, P. W. (2004). The Irony and the Tragedy of Negotiated Space: A Case Study on Narrative Form and Aboriginal-Government Relations during the Second World War. Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada, 15(1), 177–206. https://doi.org/10.7202/012073ar Tous droits réservés © The Canadian Historical Association/La Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit historique du Canada, 2004 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ chajournal2004.qxd 12/01/06 14:12 Page 177 The Irony and the Tragedy of Negotiated Space: A Case Study on Narrative Form and Aboriginal- Government Relations during the Second World War P. -

Doing Together What We Can't Do Alone

DOING TOGETHER WHAT WE CAN’T DO ALONE Inglewood Bird Sanctuary Science School Chevron Canada officially launches Chevron Open Minds School Program and contributes $1,000,000 over 5 years to help students learn in hands-on environments at the Calgary Zoo, Glenbow Museum and Calgary Science Centre. DON HA R E V Science Centre pilot classes are introduced at D N I E D K Science School (1997-present). Funded by Chevron Canada. Y O K R C Library School Jube School Tinker School Strong Kids School Jube School Library School Seed School N A A Canada Olympic Park (Winsport) Campus L A L I E G L G Calgary classes are introduced (1997-2012). A L I N R A Five new pilots were introduced to Campus Calgary: G Y Leighton Arts Centre pilots Campus Calgary (2007). Z Funded by TransAlta, CODA and RBC Foundation. O O The Calgary Public Library - Library School Inglewood Bird Sanctuary joins Campus Calgary as Bird Aero Space Museum City of Calgary, Calgary Parks pilots Campus Calgary at School and Nature School (1997-2013). Reader Rock Garden (2007, 2012-2013). Aero Space Museum (Hangar Flight Museum) launches Funded by City of Calgary, Calgary Parks. The Mustard Seed - Seed School In partnership with the Calgary Zoo, a forward thinking Funded by Petro-Canada/Suncor. Canada Olympic Park Campus Calgary Aero Space School (2005-2017). Funded by City Healthy Living School Healthy Living School educator (Gillian Kydd, Calgary Board of Education), a University of Calgary classes are offered (1997-2017). Centre for Performing Arts joins Campus Calgary (1999-2001).