Report on Equality Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Midlands Schools

List of West Midlands Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbot Beyne School Staffordshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Alcester Academy Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Alcester Grammar School Warwickshire 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Aldersley High School Wolverhampton 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Aldridge -

WEDNESBURY (Inc

HITCHMOUGH’S BLACK COUNTRY PUBS WEDNESBURY (Inc. Kings Hill, Mesty Croft) 3rd. Edition - © 2014 Tony Hitchmough. All Rights Reserved www.longpull.co.uk INTRODUCTION Well over 40 years ago, I began to notice that the English public house was more than just a building in which people drank. The customers talked and played, held trips and meetings, the licensees had their own stories, and the buildings had experienced many changes. These thoughts spurred me on to find out more. Obviously I had to restrict my field; Black Country pubs became my theme, because that is where I lived and worked. Many of the pubs I remembered from the late 1960’s, when I was legally allowed to drink in them, had disappeared or were in the process of doing so. My plan was to collect any information I could from any sources available. Around that time the Black Country Bugle first appeared; I have never missed an issue, and have found the contents and letters invaluable. I then started to visit the archives of the Black Country boroughs. Directories were another invaluable source for licensees’ names, enabling me to build up lists. The censuses, church registers and licensing minutes for some areas, also were consulted. Newspaper articles provided many items of human interest (eg. inquests, crimes, civic matters, industrial relations), which would be of value not only to a pub historian, but to local and social historians and genealogists alike. With the advances in technology in mind, I decided the opportunity of releasing my entire archive digitally, rather than mere selections as magazine articles or as a book, was too good to miss. -

Wolverhampton City Council OPEN EXECUTIVE DECISION ITEM (AMBER)

Agenda Item: 5 Wolverhampton City Council OPEN EXECUTIVE DECISION ITEM (AMBER) SPECIAL ADVISORY GROUP Date: 28 October 2011 Portfolio(s) ALL Originating Service Group(s) DELIVERY Contact Officer(s)/ SUSAN KEMBREY KEY DECISION: YES Telephone Number(s) 4300 IN FORWARD PLAN: YES Title BOUNDARY COMMISSION REVIEW OF PARLIAMENTARY CONSTITUENCIES – WEST MIDLANDS REGION CONSULTATION ON INITIAL PROPOSALS Recommendation (a) That the initial proposals of the Boundary Commission for England for the review of Parliamentary Constituencies in the West Midland region England as detailed in Sections 2 and 3 of the report be noted (b) That the Special Advisory Group recommend Cabinet to invite the three political groups to formulate their individual views on the proposals set out in the consultation paper for submission to the Boundary Commission direct. 1 1.0 PURPOSE 1.1 To advise of the consultation exercise on the initial proposals of the Boundary Commission for the review of Parliamentary Constituencies in the West Midland region and the date to respond to the consultation. 2.0 BACKGROUND 2.1 The Boundary Commission for England (BCE) is an independent and impartial non- departmental public body which is responsible for reviewing Parliamentary constituency boundaries in England. The BCE conduct a review of all the constituencies in England every five years. Their role is to make recommendations to Parliament for new constituency boundaries. The BCE is currently conducting a review of all Parliamentary constituency boundaries in England based on new rules laid down by Parliament. These rules involve a reduction in the number of constituencies in England (from 533 to 502) and stipulate that every constituency, apart from two specific exemptions, must have an electorate no smaller than 72,810 and no larger than 80,473. -

'10 Lichfield to Wednesbury' (Pdf, 512KB)

L CHF ELD STAFFORDSH RE West Midlands Key Route Network WALSALL LichfieldWOLVERHAMPTON to Wednesbury WEST BROMW CH DUDLEY BRMNGHAM WARW CKSH RE WORCESTERSH RE SOL HULL COVENTRY Figure 1 12 A5 A38, A38(M), A47, A435, A441, A4400, A4540, A5127, B4138, M6 L CHF ELD Birmingham West Midlands Cross City B4144, B4145, B4148, B4154 11a Birmingham Outer Circle A4030, A4040, B4145, B4146 Key Route Network A5 11 Birmingham to Stafford A34 Black Country Route A454(W), A463, A4444 3 2 1 M6 Toll BROWNH LLS Black Country to Birmingham A41 M54 A5 10a Coventry to Birmingham A45, A4114(N), B4106 A4124 A452 East of Coventry A428, A4082, A4600, B4082 STAFFORDSH RE East of Walsall A454(E), B4151, B4152 OXLEY A449 M6 A461 Kingswinford to Halesowen A459, A4101 A38 WEDNESF ELD A34 Lichfield to Wednesbury A461, A4148 A41 A460 North and South Coventry A429, A444, A4053, A4114(S), B4098, B4110, B4113 A4124 A462 A454 Northfield to Wolverhampton A4123, B4121 10 WALSALL A454 A454 Pensnett to Oldbury A461, A4034, A4100, B4179 WOLVERHAMPTON Sedgley to Birmingham A457, A4030, A4033, A4034, A4092, A4182, A4252, B4125, B4135 SUTTON T3 Solihull to Birmingham A34(S), A41, A4167, B4145 A4038 A4148 COLDF ELD PENN B LSTON 9 A449 Stourbridge to Wednesbury A461, A4036, A4037, A4098 A4123 M6 Stourbridge to A449, A460, A491 A463 8 7 WEDNESBURY M6 Toll North of Wolverhampton A4041 A452 A5127 UK Central to Brownhills A452 WEST M42 A4031 9 A4037 BROMW CH K NGSTAND NG West Bromwich Route A4031, A4041 A34 GREAT BARR M6 SEDGLEY West of Birmingham A456, A458, B4124 A459 M5 A38 A461 -

Review of Baseline Conditions

Walsall Site Allocation Document (SAD) and Town Centre Action Plan (AAP) Sustainability Appraisal Report (March 2016) 4. Review of ‘Baseline’ Evidence 4.1 Background to Review Appendix E to the Revised SA Scoping Report (v2 May 2013) summarises the baseline evidence reviewed by the Council at the scoping stage, by SA Topic, and Chapters 5 and 6 of the report provides a summary of existing environmental, economic and social conditions and problems, how they are likely to develop, and the areas likely to be affected. This chapter provides an updated summary of ‘baseline’ environmental, social and economic conditions, which is based on the most up-to-date evidence available at the time the SA Framework was reviewed in July 2015. The baseline date for the evidence used in the appraisal (unless otherwise specified) is April 2015, although more up-to-date information has been used where available. 4.2 Development of Evidence Base Evidence Used in Appraisal and Plan Preparation Schedule 2 of the SEA Regulations states that the SA Report should include a description of: “The relevant aspects of the current state of the environment and the likely evolution thereof without implementation of the plan or programme;” “The environmental characteristics of areas likely to be significantly affected;” and “Any existing environmental problems which are relevant to the plan or programme, including areas of particular environmental importance,” such as ‘European Sites’ designated under the Habitats and Birds Directives.1 This Chapter addresses these requirements (see Appendix P). As the SA is an integrated assessment that includes EqIA and HIA as well as SEA, the baseline evidence must include 1 These are sites of European importance for biodiversity, including sites which are designated or proposed to be designated as Special Areas of Conservation (SAC), Special Protection Areas (SPAs) and Ramsar sites. -

View Walsall's Local Climate Impacts Profile (LCLIP)

Local Climate Impacts Profile For Walsall Council Project Manager: Carol Edmondson, Climate Change Team, Walsall Council Telephone: 01922 652864 E-mail: [email protected] Research by: Groundwork Black Country Telephone: 0121 530 5500 Email: [email protected] Contents 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Background 2 1.2 Summary of results 3 1.3 Identified costs 3 1.4 Recommendations 4 2 Background 2.1 Project Background 7 2.2 Introduction to a Local Climate Impacts Profile (LCLIP) 7 2.3 Methodology 8 2.4 Classification of extreme weather impacts 8 3 The local climate and weather 3.1 Geographical context 9 3.2 Temperature 9 3.3 Precipitation 12 3.4 Wind 13 3.5 Storms 15 3.6 Frost/snow 16 3.7 Atmospheric particulates 17 3.8 Humidity 18 3.9 Climate Change 19 4 Service Impacts 4.1 Storms 21 4.2 Rain / flooding 21 4.3 Sun / heat 24 4.4 Snow and ice 26 5. Conclusion 28 Appendix 1 30 National Indicators relating to climate Appendix 2 31 Meteorological stations, glossary and references Appendix 3 32 Media Trawl Database 2 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Background The weather has historically had a major impact upon the way human society has developed. More than ever before changing weather patterns have the potential to impact heavily upon how we live our lives. It is now an accepted scientific fact that our climate is changing, and local authorities must act proactively to adapt to the world of tomorrow. The concept of ‘future proofing’ is now essential to local and central Governance. -

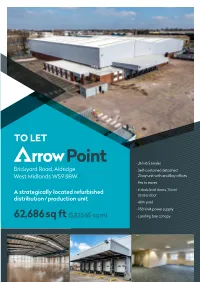

Rrow Point Rrow Point Rrow Point Rrow Point

rrow Point rro rro TO LET rrow Point • J6 M6 5.6miles Brickyard Road, Aldridge • Self-contained detached West Midlands WS9 8BW 2 bay unit with ancillary offices • 9m to eaves A strategically located refurbished • 6 dock level doors, 1 level rrow Point access door distribution/production unit • 40m yard • 950 KVA power supply 62,686sq ft (5,823.65 sq m) • Loading bay canopy w w P P oin oin t t rrow Point rrow Point Brickyard Road, Aldridge, West Midlands WS9 8BW rrow Point Location Description Terms • Aldridge is an established industrial • Comprises a detached two bay single To let, minimum term to 2023 or longer by town on the edge of the West Midlands storey warehouse constructed in the agreement. Full terms on application. conurbation. late 80s/early 90s and recently refurbished Rates • Good access to Junction 10 of the M6 • Steel portal frame construction with single approximately 5.5 miles to the south-west storey offices Current rateable value is £156,000, assessed providing access to the regions as warehouse premises. motorway network. • Power supply of 950 KVA • 6 dock level loading doors with canopy Viewing Location Mins Miles • 1 level access door Walsall Town Centre 15 4.3 Strictly by appointment only. Sutton Coldfield 16 6.4 • Secure fenced site with self-contained automatic entrance barriers with gatehouse Occupation Wolverhampton 33 10.5 Birmingham City Centre 24 12 • Approx. 40 metres yard depth with 22 lorry Available for immediate occupation, subject spaces. A tarmacadam surfaced car park to contract. M6 J10 18 5.6 with 42 spaces is situated at the front of M6 Toll JT6 5 12 the property EPC • Heating and lighting to the offices and Accommodation The building has a EPC score of C 66 and high bay lighting to the warehouse/ the full EPC Certificate is available on the production area request from the agents . -

A Short History by Margaret Brice the GROWTH of WALSALL WOOD

A Short History by Margaret Brice THE GROWTH OF WALSALL WOOD The area originally comprised three main settlements, Shelfield, Walsall Wood and Clayhanger. It consisted mainly of a wooded area on the outer edges of Cannock Wood, combined with common land until the 19th century. Walsall Wood was the main settlement of the area, the earliest recorded community being at Bullings Heath, which was at the junction of Green Lane and Hall Lane. By 1763 a settlement had grown up at Paul •s Coppice, although it did not bear that name until 1805. The area now known as Coppice Wood was originally called 'Goblin's Pit Wood'. There was once a limestone mine there and it is believed that the l imestone from that mine was used for building bridges and loc ks during t he canal building boom of the 18th and 19th centuries. The canal through Walsall Wood was opened in the 19th century, as part of the Daw End Branch of the Wyrley and Essington Canal. It started at Catshill Junction, passed southwards through Walsall Wood then on to the Hay Head limestone works and thence to Walsall. There is evidence to suggest that dwellings in Hall ' Lane, Boatman ' s Lane, Hollinder•s , Lane and Brickkiln Lane belonged to people who helped to build the canal and afterwards settled down to live in Walsall Wood. The Walsall Wood parish registers support this idea - the records include references showing that boatmen and navigators were married and buried at St. John's Church. The main road, or rather pathway, at this time ran over Walsall Wood Common to Catshill approximately in line with what are now Brownhills Road and Lindon Road. -

Rushall-Shelfield Ward Were Economically Active

Ward Walk Profile: Rushall - Shelfield January 2020 Version - FINAL Councillors Name Party Elected on: Cllr Lorna Rattigan Conservatives 11 November 2010 Cllr Vera Waters Conservatives 3 May 2018 Cllr Richard Worrall Labour 3 May 2012 Geography . Covers 5.78 sq km (578 ha) . Makes up 5.6% of the area of Walsall borough . Population density of 20.6 people per hectare (lower than borough average of 27.3) Source: Ordnance Survey; ONS, Mid-2018 Population Estimates Assets Source: Ordnance Survey Population Source: ONS, Mid-2018 Population Estimates Ethnicity . 11% minority ethnic residents . Asian is the largest minority group at 5.4% (less than the Walsall average of 15.2%) . Of the Asian minority group, Indian is the most prolific at 3.2% (6.1% borough) Source: ONS, 2011 Census Housing Composition Tenure . 4,997 households (with at least 1 usual resident) . Increase of 3.4% since 2001 (Proportion of borough total 4.6%) . Average household size: 2.4 residents per h/hold (similar to Walsall average of 2.5) . 4.2% of households ‘overcrowded’* (Walsall average 6.5%) . 3.2% of households without central heating (Walsall average 2.8%) . High proportion of socially rented (20.5%) properties compared to borough (24.1%) . Above average (31.9%) mortgage owned (37.1%) Source: ONS, 2011 Census Social Segmentation - Groups The largest groups of households are classified as group K – Modest Traditions (30%) & group H – Aspiring Homemakers (15%) Most effective communication route Least effective communication routes Source: Experian - Mosaic Public Sector Profiler 2019; Ordnance Survey LLPG Address file Economic Summary • 78.1% of working age people in Rushall-Shelfield ward were economically active. -

Greater Birmingham HMA Strategic Growth Study Appendices

Greater Birmingham HMA Strategic Growth Study Appendices Greater Birmingham & the Black Country A Strategic Growth Study into the Greater Birmingham and Black Country Housing Market Area February 2018 Prepared by GL Hearn 280 High Holborn London WC1V 7EE T +44 (0)20 7851 4900 glhearn.com Wood Plc Gables House Leamington Spa CV32 6JX T +44(0)1926 439000 woodplc.com Contents Appendices APPENDIX A: NATIONAL CHARACTER AREA PROFILES 3 APPENDIX B: SECTOR ANALYSIS 15 APPENDIX C: STRATEGIC SUSTAINABILITY APPRAISAL FRAMEWORK 47 APPENDIX D: AREA OF SEARCH APPRAISAL 61 APPENDIX E: DEVELOPMENT MODEL APPRAISAL 272 GL Hearn Page 2 of 302 APPENDIX A: National Character Area Profiles GL Hearn Page 3 of 302 61. Shropshire, Cheshire and Staffordshire Plain The Shropshire, Cheshire and Staffordshire Plain National Character Area (NCA) comprises most of the county of Cheshire, the northern half of Shropshire and a large part of north-west Staffordshire. This is an expanse of flat or gently undulating, lush, pastoral farmland, which is bounded by the Mersey Valley NCA in the north, with its urban and industrial development, and extending to the rural Shropshire Hills NCA in the south. To the west, it is bounded by the hills of the Welsh borders and to the east and south-east by the urban areas within the Potteries and Churnet Valley, Needwood and South Derbyshire Claylands, and Cannock Chase and Cank Wood NCAs. A series of small sandstone ridges cut across the plain and are very prominent features within this open landscape. The Mid-Cheshire Ridge, the Maer and the Hanchurch Hills are the most significant. -

Director of Public Health Annual Report 1999

ON THE ROAD TO BETTER HEALTH Contents The A to Z for Primary Care Groups Introduction Part One Comparative Overview of Primary Care Groups The 1999 Annual Report of Coronary Heart Disease the Director of Public Health Asthma Accidents Medicine Infections Lung Cancer and Smoking Diet Teenage pregnancy Low Birthweight Screening for Breast and Cervical Cancer Socio-economic and Health Inequality: the Walsall Composite Index of Deprivation Part Two Within the Primary Care Groups North Primary Care Group South Primary Care Group East Primary Care Group West Primary Care Group 1 Foreword Acknowledgements The development of Primary Care Groups provides I would like to thank my colleagues who were a new structure and opportunity to address the instrumental in the production of this report: public health. The main focus of this report is thus on Primary Care Groups. Editorial Team Dr John Linnane The report examines the variation in health and its Consultant, Public Health Department. determinants across the Primary Care Groups Rebecca Suri seeking to link the effects of poverty, inequalities Epidemiologist, Public Health Department and lifestyle with morbidity and mortality. Editorial Consultant This report has a number of aims which include: Steve Griffiths, Public Management Associates ■ To give the Primary Care Groups a sense of the Administrative Support communities which they serve. Helena James, Public Health Department ■ To present the type of information and analysis Contributors which is possible on a Primary Care Group and Dr Shalini Pooransingh, Specialist Registrar ward basis. Dr Mamoona Tahir, Specialist Registrar Nigel Barnes, Pharmaceutical Advisor ■ To provide a broad picture of health and its Allison Heseltine, Public Health Nurse determinants across the borough. -

Local Government Boundary Commission for England Report No

Local Government Boundary Commission For England Report No. 512. Parish Review BOROUGH OF WALSALL LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOlt ENGUMB REPORT NO. LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR ENGLAND CHAIRMAN Mr G J Ellerton CMC MBE DEPUTY CHAIRMAN Mr J G Powell FRIGS FSVA MEMBERS Lady Ackner Mr T Brockbank DL Professor G E Cherry Mr K J L Newell Mr B Scholes QBE THE RIGET HON. KENNETH BAKES KP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE ENVIRONMENT 1* In accordance with the responsibilities imposed by section ^8(8) of the Local Government Act 1972, Walsall Metropolitan Borough Council conducted a parish review and reported to us on 3 September 19#2. ^he Borough is at present completely unparished and the Borough Council's report recommends that no parishes should be created. 2. We considered the Borough Council's report and associated comments in accordance with the requirements of section ^8(9) of the 1972 Act together with the representations made direct to us by the bodies and individuals listed at Schedule A. Copies of the Borough Council's report together with copies of the representations are beinfi sent separately to your Department. 3. Although we were satisfied that the review had been carried out in accordance with the requirements of section 60 of the A"ct we nad some reservations about the extent to which 'the procedure followed could be regarded as an adequate test of public opinion in an area unfamiliar with parish government. There were indications of ft lack of widefijrad consultation with local interests and there had been only a limited attempt by the Borough Council to explain the role of parishes, 'i'nis might have led tc local feeling not emerging fully.