3-1 Chapter 3 the Oboe and Cor Anglais in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO) President

POSITION DESCRIPTION June 2021 Mississippi Symphony Orchestra (MSO) President MSO seeks a business professional who will partner with veteran Music Director & Conductor Crafton Beck, to deliver exceptional orchestral music experiences and education programs that engage and include Mississippi communities throughout the state. Founded in 1944, the Mississippi Symphony Orchestra is the cornerstone of Mississippi performing arts and has a long history of innovation, creativity, and excellence. Led by Music Director Crafton Beck and based in the City of Jackson, MSO is an innovative regional orchestra that presents orchestral music performances, programs and education of the highest quality to residents and visitors of Mississippi. Known as the “Birthplace of America’s Music,” Mississippi has shaped the course of modern music with its contributions to blues, jazz, rock, country and gospel. BACKGROUND MSO has acted as a cultural trailblazer since its founding. As the largest professional performing arts organization in the state, the financially stable MSO performs approximately 20 concerts and approximately 100 full orchestra and small ensemble educational performances statewide for more than 30,000 Mississippians each year. The Selby and Richard McRae Foundation Bravo Series is MSO’s banner classical series of 5 concerts which are annually performed along with the 2 concert Pops Series at the 2,040 seat Thalia Mara Hall in downtown Jackson, while an equally successful Chamber Orchestra Series of four concerts is performed in intimate venues throughout Jackson and the region and the popular Pepsi Pops concert is performed at a local outdoor venue. MSO tours statewide as a full orchestra, chamber orchestra in three resident ensembles - Woodwind Quintet, Brass Quintet and String Quartet with annual and bi-annual visits to Vicksburg, Pascagoula, McComb, Brookhaven, Poplarville, and other cities. -

1 Requirements for the Call to Establish the Oboe/Cor Anglais

Requirements for the call to establish the oboe/cor anglais substitution pool for the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra 1- Purpose of the call The purpose of this call is the creation of a substitution pool, with the category of Senior Professor of Music (Tutti) in the specialty of oboe/cor anglais, to be hired in the mode of temporary employment, based on the needs of the Consorci de L’Auditori i l’Orquestra in the department of the Barcelona Symphony Orchestra (hereinafter OBC). The incorporation of temporary work personnel shall be limited to the circumstances established in the regulations, in line with the general principle of hiring staff at L'Auditori by means of passing through selective processes and whenever there are reasons for the maintenance of essential services, specifically: Temporary replacement of the appointees; Increase in staff for artistic needs for the temporary execution of programmes; The incorporations in any case must be made in accordance with the conditions stemming from the budgetary regulations. The incorporation of temporary work personnel shall be governed by the labour relations of a special nature for artists in public performances provided for in the Workers’ Statute and regulated by Royal Decree 1435/1985. The remuneration and the working hours shall be that agreed upon in the collective bargaining agreement. 2- Requirements for participation All requirements must be met by the deadline for submission of applications and must be maintained for as long as the employment relationship with the Consorci de l’Auditori i l’Orquestra should last. - Be at least 16 years of age and not exceed the age established for forced retirement. -

Instruments of the Orchestra

INSTRUMENTS OF THE ORCHESTRA String Family WHAT: Wooden, hollow-bodied instruments strung with metal strings across a bridge. WHERE: Find this family in the front of the orchestra and along the right side. HOW: Sound is produced by a vibrating string that is bowed with a bow made of horse tail hair. The air then resonates in the hollow body. Other playing techniques include pizzicato (plucking the strings), col legno (playing with the wooden part of the bow), and double-stopping (bowing two strings at once). WHY: Composers use these instruments for their singing quality and depth of sound. HOW MANY: There are four sizes of stringed instruments: violin, viola, cello and bass. A total of forty-four are used in full orchestras. The string family is the largest family in the orchestra, accounting for over half of the total number of musicians on stage. The string instruments all have carved, hollow, wooden bodies with four strings running from top to bottom. The instruments have basically the same shape but vary in size, from the smaller VIOLINS and VIOLAS, which are played by being held firmly under the chin and either bowed or plucked, to the larger CELLOS and BASSES, which stand on the floor, supported by a long rod called an end pin. The cello is always played in a seated position, while the bass is so large that a musician must stand or sit on a very high stool in order to play it. These stringed instruments developed from an older instrument called the viol, which had six strings. -

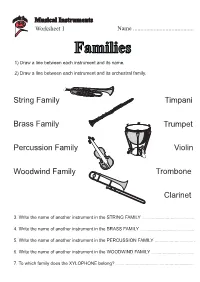

Families 2) Draw a Line Between Each Instrument and Its Orchestral Family

Musical Instruments Worksheet 1 Name ......................................... 1) Draw a line between each instrument and its name.Families 2) Draw a line between each instrument and its orchestral family. String Family Timpani Brass Family Trumpet Percussion Family Violin Woodwind Family Trombone Clarinet 3. Write the name of another instrument in the STRING FAMILY .......................................... 4. Write the name of another instrument in the BRASS FAMILY ........................................... 5. Write the name of another instrument in the PERCUSSION FAMILY ................................ 6. Write the name of another instrument in the WOODWIND FAMILY .................................. 7. To which family does the XYLOPHONE belong? ............................................................... Musical Instruments Worksheet 3 Name ......................................... Multiple Choice (Tick the correct family) String String String Oboe Brass Double Brass Bass Brass Woodwind bass Woodwind drum Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cymbals Brass Bassoon Brass Trumpet Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String French Brass Cello Brass Clarinet Brass horn Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Cor Brass Trombone Brass Saxophone Brass Anglais Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion Percussion String String String Viola Brass Castanets Brass Euphonium Brass Woodwind Woodwind Woodwind Percussion Percussion -

5-1 Shostakovich's Knowledge and Understanding of the Oboe and Cor

5-1 CHAPTERS MELODIC ASPECTS 5.1 Introduction Shostakovich's knowledge and understanding of the oboe and cor anglais are clearly reflected in the allocation of solo material throughout his 15 symphonies. 5.2 Allocation of solo material to the oboe Although the oboe is clearly not Shostakovich's favourite instrument, the solo material reveals a deft understanding of the instrument's technical and lyrical capabilities. Symphonies No.2, 11 and 13, however, have no solos for the oboe. The oboes are not used in Symphony No. 14 as it is scored for strings, percussion and soloists. As early as Symphony No. 1 Shostakovich establishes himself with insight as an orchestrator of oboe solos. A wide range of dynamic indications accompany the oboe solos, unlike the cor anglais whose predominantly allocated dynamic range is piano. Shostakovich writes very sympathetically for the player by not exhausting his stamina and by allowing sufficient rests in solo passages and avoiding long phrases. Solo passages are sometimes given to the second oboe and cor anglais in unison or in thirds, sixths or otherwise (see Ex. 5-5). Solo passages are also sometimes shared with other woodwind instruments. Oboe solos are generally approximately 8 bars long, although longer solos are found in Symphonies No.1, 4, 7 and 10 with 16 or more bars in length. The first movement of Symphony No.7 has the longest solo of 35 bars in which the bassoon and first oboe have solos in free imitation. Oboe solos are often supported by a characteristic tremolo string accompaniment, or by sustained strings or low woodwinds. -

New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon

Hayley Elizabeth Roud 300220780 NZSM596 Supervisor- Professor Donald Maurice Master of Musical Arts Exegesis 10 December 2010 New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon Contents 1 Introduction 3 2.1 History of the contrabassoon in the international context 3 Development of the instrument 3 Contrabassoonists 9 2.2 History of the contrabassoon in the New Zealand context 10 3 Selected New Zealand repertoire 16 Composers: 3.1 Bryony Jagger 16 3.2 Michael Norris 20 3.3 Chris Adams 26 3.4 Tristan Carter 31 3.5 Natalie Matias 35 4 Summary 38 Appendix A 39 Appendix B 45 Appendix C 47 Appendix D 54 Glossary 55 Bibliography 68 Hayley Roud, 300220780, New Zealand Works for Contrabassoon, 2010 3 Introduction The contrabassoon is seldom thought of as a solo instrument. Throughout the long history of contra- register double-reed instruments the assumed role has been to provide a foundation for the wind chord, along the same line as the double bass does for the strings. Due to the scale of these instruments - close to six metres in acoustic length, to reach the subcontra B flat’’, an octave below the bassoon’s lowest note, B flat’ - they have always been difficult and expensive to build, difficult to play, and often unsatisfactory in evenness of scale and dynamic range, and thus instruments and performers are relatively rare. Given this bleak outlook it is unusual to find a number of works written for solo contrabassoon by New Zealand composers. This exegesis considers the development of contra-register double-reed instruments both internationally and within New Zealand, and studies five works by New Zealand composers for solo contrabassoon, illuminating what it was that led them to compose for an instrument that has been described as the 'step-child' or 'Cinderella' of both the wind chord and instrument makers. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan TRANSFORMATIONS of HARMONY AND

TRANSFORMATIONS OF HARMONY AND CONSISTENCIES OF FORM IN THE SIX ORGAN SYMPHONIES OF LOUIS VIERNE Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Long, Page Carroll, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 21:01:35 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/284469 This dissertation has been 63-6725 microfilmed exactly as received LONG, Page Carroll, 1933- TRANSFORMATIONS OF HARMONY AND CON SISTENCIES OF FORM IN THE SIX ORGAN SYMPHONIES OF LOUIS VIERNE. University of Arizona, A.Mus.D., 1963 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan TRANSFORMATIONS OF HARMONY AND CONSISTENCIES OF FOFM IN THE SIX ORGAN SYMPHONIES OF LOUIS VIERNE by v Page CiLong A Paper Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1963 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Page G. Long entitled TranaformationB of harmony and consistencies of form in the six organ symphonies of Louis Vierne. be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of A.Mus.D. <==»^Di ssertation Director Date After inspection of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:* 6 -3 1 ~ 6, 3 <9.^w. -

The Source Spectrum of Double-Reed Wood-Wind Instruments

Dept. for Speech, Music and Hearing Quarterly Progress and Status Report The source spectrum of double-reed wood-wind instruments Fransson, F. journal: STL-QPSR volume: 8 number: 1 year: 1967 pages: 025-027 http://www.speech.kth.se/qpsr MUSICAL ACOUSTICS A. THE SOURCE SPECTRUM OF DOUBLE-REED WOOD-VIIND INSTRUMENTS F. Fransson Part 2. The Oboe and the Cor Anglais A synthetic source spectrum for the bassoon was derived in part 1 of the present work (STL-GPSR 4/1966, pp. 35-37). A synthesis of the source spectrum for two other representative members of the double-reed family is now attempted. Two oboes of different bores and one cor anglais were used in this experiment. Oboe No. 1 of the old system without marking, manufactured in Germany, has 13 keys; Oboe No. 2, manufactured in France and marked Gabart, is of the modern system; and the Cor Anglais No. 3 is of the old system with 13 keys and made by Bolland & Wienz in Hannover. Measurements A mean spectrogram for tones within one octave covering a frequen- cy range from 294 to 588 c/s was produced for the oboes by playing two scrics of tones. One serie was d4, e4, f4, g4, and a and the other 4 serie was g 4, a4, b4, c 5' and d5. Both series were blown slurred ascending and descending in rapid succession, recorded and combined to a rather inharmonic duet on one loop. The spectrograms are shown in Fig. 111-A- 1 whcre No. 1 displays the spectrogram for the old sys- tem German oboe and No. -

Gr. 4 to 8 Study Guide

Toronto Symphony TS Orchestra Gr. 4 to 8 Study Guide Conductors for the Toronto Symphony Orchestra School Concerts are generously supported by Mrs. Gert Wharton. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra’s School Concerts are generously supported by The William Birchall Foundation and an anonymous donor. Click on top right of pages to return to the table of contents! Table of Contents Concert Overview Concert Preparation Program Notes 3 4 - 6 7 - 11 Lesson Plans Artist Biographies MusicalGlossary 12 - 38 39 - 42 43 - 44 Instruments in Musicians Teacher & Student the Orchestra of the TSO Evaluation Forms 45 - 56 57 - 58 59 - 60 The Toronto Symphony Orchestra gratefully acknowledges Pierre Rivard & Elizabeth Hanson for preparing the lesson plans included in this guide - 2 - Concert Overview No two performances will be the same Play It by Ear! in this laugh-out-loud interactive February 26-28, 2019 concert about improvisation! Featuring Second City alumni, and hosted by Suitable for grades 4–8 Kevin Frank, this delightfully funny show demonstrates improvisatory techniques Simon Rivard, Resident Conductor and includes performances of orchestral Kevin Frank, host works that were created through Second City Alumni, actors improvisation. Each concert promises to Talisa Blackman, piano be one of a kind! Co-production with the National Arts Centre Orchestra Program to include excerpts from*: • Mozart: Overture to The Marriage of Figaro • Rimsky-Korsakov: Scheherazade, Op. 35, Mvt. 2 (Excerpt) • Copland: Variations on a Shaker Melody • Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, Mvt. 4 (Excerpt) • Holst: St. Pauls Suite, Mvt. 4 *Program subject to change - 3 - Concert Preparation Let's Get Ready! Your class is coming to Roy Thomson Hall to see and hear the Toronto Symphony Orchestra! Here are some suggestions of what to do before, during, and after the performance. -

Woodwind Family

Woodwind Family What makes an instrument part of the Woodwind Family? • Woodwind instruments are instruments that make sound by blowing air over: • open hole • internal hole • single reeds • double reed • free reeds Some woodwind instruments that have open and internal holes: • Bansuri • Daegeum • Fife • Flute • Hun • Koudi • Native American Flute • Ocarina • Panpipes • Piccolo • Recorder • Xun Some woodwind instruments that have: single reeds free reeds • Clarinet • Hornpipe • Accordion • Octavin • Pibgorn • Harmonica • Saxophone • Zhaleika • Khene • Sho Some woodwind instruments that have double reeds: • Bagpipes • Bassoon • Contrabassoon • Crumhorn • English Horn • Oboe • Piri • Rhaita • Sarrusaphone • Shawm • Taepyeongso • Tromboon • Zurla Assignment: Watch: Mr. Gendreau’s woodwind lesson How a flute is made How bagpipes are made How a bassoon reed is made *Find materials in your house that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) can use to make a woodwind (i.e. water bottle, straw and cup of water, piece of paper, etc). *Find some other materials that you (with your parent’s/guardian’s permission) you can make a different woodwind instrument. *What can you do to change the sound of each? *How does the length of the straw effect the sound it makes? *How does the amount of water effect the sound? When you’re done, click here for your “ticket out the door”. Some optional videos for fun: • Young woman plays music from “Mario” on the Sho • Young boy on saxophone • 9 year old girl plays the flute. -

Chamber & Ensemble Music

Chamber & Ensemble Music New Releases 2000–2011 Contents I. WORKS BY COMPOSER – Alphabetical List ���������������������������������������������������������� p.3 A. New compositions and arrangements �������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 B. Additions to the catalogue ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 25 II. WORKS BY GENRE ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 30 1. Solo instrumental (also with accompaniment) ������������������������������������������������������� 30 1.1. Violin ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 30 1.2. Viola ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31 1.3. Cello ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 31 1.4. Double bass ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 32 1.5. Flute ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 1.6. Oboe ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 1.7. Clarinet/Bass clarinet ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Reed Instruments About Reeds

Reed Instruments About Reeds A reed is a thin elastic strip of cane fixed at one end and free at the other. It is set into vibration by moving air. Reeds are the sound generators in the instruments described below. Cane reeds are built as either double or single reeds. A double reed consists of two pieces of cane carved and bound into a hollow, round shape at one end and flattened out and shaved thin at the other. The two pieces are tied together to form an channel. The single reed is a piece of cane shaved at one end and fastened at the other to a mouthpiece. Single Reed Instruments Clarinet: A family of single reed instruments with mainly a cylindrical bore. They are made of grenadilla (African blackwood) or ebonite, plastic, and metal. Clarinets are transposing instruments* and come in different keys. The most common ones used in orchestras are the clarinet in A and the clarinet in Bb. When a part calls for a clarinet in A, the player may either double -i.e. play the clarinet in A, or play the clarinet in Bb and transpose* the part as he plays. During the time of Beethoven, the clarinet in C was also in use and players were expected to be able to play all three instruments when required. All clarinets are notated in the treble clef and have approximately the same written range: E below middle C to c´´´´ (C five ledger lines above the staff). Bass Clarinet: A member of the clarinet family made of wood, which sounds an octave lower than the Clarinet in Bb.