SEVERE CONVECTIVE WIND ENVIRONMENTS in GEORGIA By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NCAR Annual Scientific Report April 1978 - March 1979 - Link Page Next PART0002

National Center for Atmospheric Research Annual Scientific Report April 1978-March 1979 Submitted to National Science Foundation by University Corporation for Atmospheric Research July 1979 * * iii11 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION v ATMOSPHERIC ANALYSIS AND PREDICTION DIVISION 1 Climate Section 7 Oceanography Section 15 Large-Scale Dynamics Section 19 Mesoscale Research Section 28 ATMOSPHERIC QUALITY DIVISION 37 In-Situ Measurements and Photochemical Modeling 39 Biosphere-Atmosphere Interaction 42 Gas and Aerosol Measurements 43 Global Observations, Modeling, and Optical Techniques 45 Reactive Gases and Particles 51 Thermospheric Dynamics and Aeronomy 53 Stratospheric-Tropospheric Exchange 56 Radioactive Aerosols and Effects 58 HIGH ALTITUDE OBSERVATORY 63 Solar Variability Section 65 Solar Atmosphere and Magnetic Fields Section 72 Coronal Physics Section 78 78 Interplanetary Physics Section 83 CONVECTIVE STORMS DIVISION 89 ADVANCED STUDY PROGRAM 113 ATMOSPHERIC TECHNOLOGY DIVISION 127 Research Aviation Facility 129 Computing Facility 141 Field Observing Facility 154 Research Systems Facility 163 Global Atmospheric Measurements Program 169 National Scientific Balloon Facility 176 PUBLICATIONS 183 v INTRODUCTION The UCAR-NSF contract for the operation of NCAR calls for UCAR to submit to NSF an annual scientific report "containing a scientific description of all programs conducted by NCAR staff and NCAR visitors during the previous year." The contract stipulates that the report should "include a description of the scientific problems placed in a larger context, accomplishments, and a listing of papers published." This document is designed to respond to that contract provision, and has as its primary audience those NSF staff members responsible for monitoring UCAR's performance in the operation of a national laboratory under NSF sponsorship. -

Title Author(S)

th 5 European Conference on Severe Storms 12 - 16 October 2009 - Landshut - GERMANY ECSS 2009 Abstracts by session ECSS 2009 - 5th European Conference on Severe Storms 12-16 October 2009 - Landshut – GERMANY List of the abstract accepted for presentation at the conference: O – Oral presentation P – Poster presentation Session 09: Severe storm case studies and field campaigns, e.g. COPS, THORPEX, VORTEX2 Page Type Abstract Title Author(s) An F3 downburst in Austria - a case study with special G. Pistotnik, A. M. Holzer, R. 265 O focus on the importance of real-time site surveys Kaltenböck, S. Tschannett J. Bech, N. Pineda, M. Aran, J. An observational analysis of a tornadic severe weather 267 O Amaro, M. Gayà, J. Arús, J. event Montanyà, O. van der Velde Case study: Extensive wind damage across Slovenia on July M. Korosec, J. Cedilnik 269 O 13th, 2008 Observed transition from an elevated mesoscale convective J. Marsham, S. Trier, T. 271 O system to a surface based squall line: 13th June, Weckwerth, J. Wilson, A. Blyth IHOP_2002 08/08/08: classification and simulation challenge of the A. Pucillo, A. Manzato 273 O FVG olympic storm H. Bluestein, D. Burgess, D. VORTEX2: The Second Verification of the Origins of Dowell, P. Markowski, E. 275 O Rotation in Tornadoes Experiment Rasmussen, Y. Richardson, L. Wicker, J. Wurman Observations of the initiation and development of severe A. Blyth, K. Browning, J. O convective storms during CSIP Marsham, P. Clark, L. Bennett The development of tornadic storms near a surface warm P. Groenemeijer, U. Corsmeier, 277 O front in central England during the Convective Storm C. -

Dissertation Cold Pool Processes in Different

DISSERTATION COLD POOL PROCESSES IN DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS Submitted by Leah Danielle Grant Department of Atmospheric Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Spring 2018 Doctoral Committee: Advisor: Susan C. van den Heever David A. Randall Steven A. Rutledge Jeffrey D. Niemann Copyright by Leah Danielle Grant 2017 All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT COLD POOL PROCESSES IN DIFFERENT ENVIRONMENTS Cold pools are localized regions of dense air near Earth’s surface. They form in association with precipitating clouds in many environments ranging from moist tropical to semi- arid continental conditions, and they play important roles in weather in climate. The overarching goal of this dissertation research is to improve our process-level understanding of cold pool interactions with different components of the Earth system, focusing on two key knowledge gaps: (1) interactions with Earth’s surface in continental environments; and (2) interactions with organized convective systems in tropical oceanic environments. The primary goal of the first study conducted in this dissertation is to evaluate how surface sensible heat fluxes impact cold pool dissipation in dry continental environments via two pathways: (a) by directly heating the cold pool, and (b) by changing mixing rates between cold pool air and environmental air through altering turbulence intensity. Idealized 2D simulations of isolated cold pools are conducted with varying sensible heat flux formulations to determine the relative importance of these two mechanisms. The results demonstrate that the impact of sensible heat fluxes on mixing, i.e. mechanism (b), contributes most significantly to cold pool dissipation. -

THE BOW ECHO and MCV EXPERIMENT Observations and Opportunities

THE BOW ECHO AND MCV EXPERIMENT Observations and Opportunities BY CHRISTOPHER DAVIS, NOLAN ATKINS, DIANA BARTELS, LANCE BOSART, MICHAEL CONIGLIO, GEORGE BRYAN, WILLIAM COTTON, DAVID DOWELL, BRIAN JEWETT, ROBERT JOHNS,* DAVID JORGENSEN, JASON KNIEVEL, KEVIN KNUPP, WEN-CHAU LEE, GREGORY MCFARQUHAR, JAMES MOORE, RON PRZYBYLINSKI, ROBERT RAUBER, BRADLEY SMULL, ROBERT TRAPP, STANLEY TRIER, ROGER WAKIMOTO, MORRIS WEISMAN, AND CONRAD ZIEGLER The field campaign, involving multiple aircraft and ground-based instruments, documented numerous long-lived mesoscale convective systems, many producing strong surface winds and exhibiting mesoscale rotation. hile the observational study of mesoscale Kansas Preliminary Regional Experiment for convective systems (MCSs) has been active Stormscale Operational and Research Meteorology W since the 1940s (e.g., Newton 1950 and ref- (STORM)-Central (PRE-STORM) (Cunning 1986) erences within), until the Bow Echo and Mesoscale were geographically fixed by the ground-based instru- Convective Vortex Experiment (BAMEX) there were ment networks employed. The unique observing no studies designed to sample multiscale aspects of strategy of BAMEX relied on the deployment of these systems throughout the majority of their life highly mobile observing systems, both airborne and cycles. Previous field studies such as the Oklahoma- ground based, supported by the enhanced operational AFFILIATIONS: DAVIS, BRYAN, DOWELL, KNIEVEL, BARTELS, LEE, Missouri; SMULL—NSSL, and University of Washington, Seattle, TRIER, AND WEISMAN—National -

Fp5j.2 an Airborne Dual-Doppler Back-Trajectory Study of Downdrafts in Bow-Echoes During Bamex

FP5J.2 AN AIRBORNE DUAL-DOPPLER BACK-TRAJECTORY STUDY OF DOWNDRAFTS IN BOW-ECHOES DURING BAMEX William C. Straka III+, William R. Cotton*, and Ray McAnelly Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado + Current affiliation: Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin at Madison, Madison, WI 1. INTRODUCTION Mesoscale convective systems (MCSs) have been observed to often produce severe windstorms, which can pose a significant hazard to life and property. These windstorms often occur in much of the United States during the spring and summer months, coincidentally the same time that most MCSs occur in the mid-west. Johns and Hirt (1987) defined the long-lived, large scale convectively produced windstorms, called derechos, basing their criteria on data available from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC) and the National Severe Storms Forecast Center (the predecessor to the Storm Prediction Center; SPC). Johns and Hirt (1987) defined derecho events to be associated with an extratropical MCS that produces a “family of downburst clusters” (Fujita and Wakimoto, 1981). Based on the criteria of Johns and Hirt (1987), the geographical distribution of the 70 Figure 1. Total number of derechos in a 2o x 2o warm season events they observed suggest that most squares during May through August 1980-1981. warm season derechos occur in a region from the Interpreted from Johns and Hirt (1987). upper Midwest to the Ohio valley and are relatively infrequent in other locations (Figure 1). It is thought line winds, they also have been associated with the that most derechos are manifestations of “bow- formation of tornados (e. -

Characteristic Analysis of the Downburst in Greely, Colorado on 30 July 2017 Using WPEA Method and X-Band Radar Observations

atmosphere Article Characteristic Analysis of the Downburst in Greely, Colorado on 30 July 2017 Using WPEA Method and X-Band Radar Observations Hao Wang 1,*, Venkatachalam Chandrasekar 2, Jianxin He 3, Zhao Shi 1 and Lijuan Wang 1 1 College of Atmospheric Sounding, Chengdu University of Information Technology, Chengdu 610225, China; [email protected] (Z.S.); [email protected] (L.W.) 2 College of Engineering, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80521, USA; [email protected] 3 Key Open Laboratory of Atmospheric Sounding, Chengdu University of Information and Technology, Chengdu 610225, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-028-859-67291 Received: 10 June 2018; Accepted: 4 September 2018; Published: 6 September 2018 Abstract: As a manifestation of low-altitude wind shear, a downburst is a localized, strong downdraft that can lead to disastrous wind on the ground surface. For effective pre-warning and forecasting of downbursts, it is particularly critical to understand relevant weather features that occur before and during a downburst process. It is important to identify the macroscopic features associated with the downburst weather process before considering fine-scale observations because this would greatly increase the accuracy and timeliness of forecasts. Therefore, we applied the wind-vector potential-temperature energy analysis (WPEA) method and CSU-CHILL X-band dual-polarization radar to explore the features of the downburst process. Here it was found that prior to the occurrence of the downburst of interest, the specific areas that should be monitored in future events could be determined by studying the atmospherically unstable areas using the WPEA method. -

Doppler Radar Meteorological Observations

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE/ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration OFFICE OF THE FEDERAL COORDINATOR FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH FEDERAL METEOROLOGICAL HANDBOOK NO. 11 DOPPLER RADAR METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATIONS PART B DOPPLER RADAR THEORY AND METEOROLOGY FCM-H11B-2005 Washington, DC December 2005 THE FEDERAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (FCMSSR) VADM CONRAD C. LAUTENBACHER, JR., USN (RET.) MR. RANDOLPH LYON Chairman, Department of Commerce Office of Management and Budget DR. SHARON HAYS (Acting) MR. CHARLES E. KEEGAN Office of Science and Technology Policy Department of Transportation DR. RAYMOND MOTHA MR. DAVID MAURSTAD (Acting) Department of Agriculture Federal Emergency Management Agency Department of Homeland Security BRIG GEN DAVID L. JOHNSON, USAF (RET.) Department of Commerce DR. MARY L. CLEAVE National Aeronautics and Space MR. ALAN SHAFFER Administration Department of Defense DR. MARGARET S. LEINEN DR. ARISTIDES PATRINOS National Science Foundation Department of Energy MR. PAUL MISENCIK DR. MAUREEN MCCARTHY National Transportation Safety Board Science and Technology Directorate Department of Homeland Security MR. JAMES WIGGINS U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission DR. MICHAEL SOUKUP Department of the Interior DR. LAWRENCE REITER Environmental Protection Agency MR. RALPH BRAIBANTI Department of State MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON Federal Coordinator MR. JAMES B. HARRISON, Executive Secretary Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research THE INTERDEPARTMENTAL COMMITTEE FOR METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES AND SUPPORTING RESEARCH (ICMSSR) MR. SAMUEL P. WILLIAMSON, Chairman MS. LISA BEE Federal Coordinator Federal Aviation Administration Department of Transportation MR. THOMAS PUTERBAUGH Department of Agriculture DR. JONATHAN M. BERKSON United States Coast Guard MR. JOHN E. JONES, JR. Department of Homeland Security Department of Commerce MR. -

Transient Analysis of Full Scale and Experimental Downburst Flows

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-26-2018 1:30 PM Transient Analysis of Full Scale and Experimental Downburst Flows Junayed Chowdhury The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Hangan,Horia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Civil and Environmental Engineering A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Engineering Science © Junayed Chowdhury 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Aerodynamics and Fluid Mechanics Commons, Civil and Environmental Engineering Commons, Environmental Design Commons, and the Mechanical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Chowdhury, Junayed, "Transient Analysis of Full Scale and Experimental Downburst Flows" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5861. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5861 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Downbursts are highly transient natural phenomena which produce strong downdrafts evolving from a cumulonimbus cloud They induce an outburst of damaging winds on or near to the ground causing an immense damage to the ground mounted structures and aircrafts. This study investigates the transient nature of downbursts using wind speed records from full scale downburst events employing an objective methodology. This method can detect the abrupt change points in a downburst time series based on statistical parameters such as mean, standard deviation and linear trend. In addition to the analysis of the full scale downburst events, several large scale experimental model downbursts are produced in the Wind Engineering, Energy and Environment (WindEEE) Dome at Western University by varying downdraft jet diameter and jet velocity to comprehensively characterize the downburst flow field. -

P2.2 the Importance of Acars Data in Evaluating the Near-Storm Environment of a Nocturnal Qlcs Event

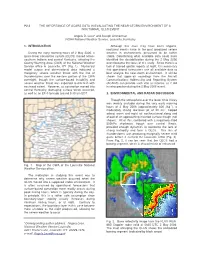

P2.2 THE IMPORTANCE OF ACARS DATA IN EVALUATING THE NEAR-STORM ENVIRONMENT OF A NOCTURNAL QLCS EVENT Angela D. Lese* and Joseph Ammerman NOAA/National Weather Service, Louisville, Kentucky 1. INTRODUCTION Although this case may have been atypical, nocturnal events have in the past produced severe During the early morning hours of 2 May 2006, a weather in environments presumed to be rather quasi-linear convective system (QLCS) moved across stable. Determining what available data could have southern Indiana and central Kentucky, affecting the identified the destabilization during the 2 May 2006 County Warning Area (CWA) of the National Weather event became the focus of this study. Since there is a Service office in Louisville, KY (Fig. 1). Numerical lack of trained spotter reports at night, it is necessary model output and observational data indicated a that operational forecasters use all available data to marginally severe weather threat with the line of best analyze the near-storm environment. It will be thunderstorms over the western portion of the CWA shown that upper-air soundings from the Aircraft overnight, though the surface-based instability and Communications Addressing and Reporting System severe weather threat was expected to diminish with (ACARS) can provide such vital assistance, as it did eastward extent. However, as convection moved into in retrospection during the 2 May 2006 event. central Kentucky, damaging surface winds occurred, as well as an EF-0 tornado around 5:30 am EDT. 2. ENVIRONMENTAL AND RADAR DISCUSSION Though the atmosphere over the lower Ohio Valley was weakly unstable during the very early morning hours of 2 May 2006 (approximately 800 Jkg-1), a -1 moderately strong low-level jet of 20 ms helped advect warm and moist air northeastward along and ahead of an approaching inverted surface trough (not shown). -

Characteristics of Microbursts in the Continental United States

Wolison - Characteristics of Microbursts in the Continental United States scale gust fronts - abrupt shifts in wind direc- tion with corresponding increases in wind speed. Rather than encountering downbursts, they believed that the aircraft had encountered the turbulent leading edges of oufflows from large-scale storm systems and the strong, but unidirectional, horizontal winds just behind them. Part of this argument was based on de- tailed analyses of windfields in springtime tor- nadic storms and of 'squall lines in Oklahoma, in which no small-scale downdrafts were found [8,91. In his early papers [ 10,111, Fujita explained Fig. 1 - Downdrafts from a thunderstorm can be haz- the differences between downbursts and gust ardous to an airplane during a takeoff. (Redrawn from fronts, especiallywith regard to the wind shear Ref 2). hazard they posed for aviation. Nonetheless, skepticism of the microburst as a distinct phe- nomenon persisted. This skepticismpoints out on the aircraft), then it is a downburst [6]. the crucial importance of differentiating be- A few years after the downburst was defined, tween storm types that occur in different parts the term "microburst**was created to distin- of the country at different times of the year. It guish small downbursts (0.8 to 4.0 km in hori- also highlights the need for understanding the zontal scale) from larger ones [7].(No reason changes in surface wind shear patterns that based on aerodynamic principles or fluid dy- occur as these storms evolve. namics sets 4 km as the upper limit of a rnicro- The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) burst, but the 0.8-km minimum does have a developed the anemometer-based Low Level fundamental basis. -

11C.7 Treating Landfalling Hurricanes As Mesoscale Convective Systems - a Paradigm Shift for Weather Forecast Operations

11C.7 TREATING LANDFALLING HURRICANES AS MESOSCALE CONVECTIVE SYSTEMS - A PARADIGM SHIFT FOR WEATHER FORECAST OPERATIONS Scott M. Spratt*, Bartlett C. Hagemeyer, and David W. Sharp NOAA / National Weather Service, Melbourne, Florida 1. INTRODUCTION special local bulletins/warnings for significant/extreme winds. Several past high impact events will be analyzed On July 25, 2006, ten leading hurricane and climate in the context of applying the paradigm shift to scientists released a Statement on the U.S. Hurricane forecast/warning operations. The need for both internal Problem (Emmanuel et al. 2006). The statement read (NWS) and external training and outreach efforts on the “…the main hurricane problem facing the United States new approaches will be briefly addressed. The (is) the ever-growing concentration of population and concluding section will summarize the suggested wealth in vulnerable coastal regions. These approach and strategies and illustrate how such an demographic trends are setting us up for rapidly application will lead to more streamlined services, while increasing human and economic losses from hurricane providing crucial, non-contradictory information to disasters, especially in this era of heightened activity.” complement NHC products. The authors believe the utility of the approach will become evident as additional In order to better serve the public as a hurricane life-saving measures are enacted by citizens in the final landfall becomes imminent, providing accurate and moments prior to destructive hurricane wind impacts timely weather information at a higher frequency and with greater detail and resolve than is often presently 2. ADOPTING THE PARADIGM SHIFT accomplished becomes critical. Short-fused bulletins focusing on the most dangerous localized wind impacts At the local WFO level, the traditional mode of must be issued in such a way as to cut through the operation for dealing with the tropical cyclone (TC) core information barrage, thereby elevating the urgency of has been to treat the system as synoptic in nature. -

South Dakota's

1 Evolution of the South Dakota Tornado Outbreak of 24 June 2003 JAY TROBEC 1 Sioux Falls, SD Corresponding author address: Dr. Jay Trobec, KELO-TV, 501 South Phillips Avenue, Sioux Falls, SD 57104. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Abstract Several intriguing factors contributed to the single-day record tornado outbreak in South Dakota on 24 June 2003. One-half of the 67 tornadoes occurred in a warm sector which was weakly-sheared due to a substantially unidirectional flow. Strong surface heating and very steep low-level lapse rates promoted initiation of these tornadoes, many of which then exhibited unusual southeast-to-northwest movement. It was not the trochoidal curl motion documented in many previous events at the end of a longer-track tornado life cycle; radar data suggest it was instead the mechanism of mid-level mesocyclonic rotation which caused the tornado vortexes to veer cyclonically to the left (northwest quadrant) of the parent storm’s movement throughout their lifetimes. Another supercell during the outbreak, near a surface-low pressure center, also produced a tornado which moved left of observed storm motion - though it was not as deviant as the tornado movement that occurred in the warm sector, and appeared to be related to the rear-flank downdraft and a preexisting convergence boundary. The anomalous tornado movements confirmed to operational forecasters that storm motion and tornado motion are not equivalent. There are many papers in the meteorological literature about other notable tornado outbreaks, such as the 3 May 1999 outbreak around Oklahoma City (e.g. Thompson and Edwards, 2000; Edwards et al., 2002B), and the “Super Outbreak” on 3 April 1974 (Corfidi et al., 2004).