Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notification Pgm-Cet-2014

No.DMER/PGM-CET 2014/Question Paper/Notification No.5/2-A, Date : 28/01/2014. NOTIFICATION PGM-CET-2014 The Common Entrance Test for Postgraduate Medical Courses, PGM-CET-2014 was conducted on Sunday, 5th January, 2014 by Competent Authority appointed by Government of Maharashtra. The provisional result of the same is being declared on 28th January 2014. The subject experts have opined that seven (07) questions in the question paper of the aforesaid examination are defective. The Competent Authority, on the basis of the opinion and advice of the respective subject expert has taken a decision to make these seven (07) questions "non-evaluative / invalid". These questions carried one mark each for a correct answer. Therefore instead of reducing the maximum number of marks from 300 to 293, The Competent Authority has decided to allot one mark each for these defective MCQ to all candidates who appeared in this examination, thus keeping maximum marks as 300; unchanged. The details of "Non-evaluative/ Invalid" MCQ are shown in the Table No. - 1 at respective Sr. No. in each version. Table No. – 1 – Version-wise Sr. No. of Non-evaluative/ Invalid Questions Sr. No. in Sr. No. in Sr. No. Sr. No. Sr. No. Version 11 Version 22 in Version 33 in Version 44 1 54 44 19 294 2 60 75 50 25 3 129 164 139 114 4 157 202 177 152 5 181 21 296 271 6 194 184 159 134 7 199 134 109 84 The subject expert also opined that there is change in Answer Key in Four (04) questions. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Andhra in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 307,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 307,800 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Telugu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.86% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi Karnataka in India Agamudaiyan in India Population: 2,974,000 Population: 888,000 World Popl: 2,974,000 World Popl: 906,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Kannada Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.51% Chr Adherents: 0.50% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan Nattaman -

The Kingdom of Afghanistan: a Historical Sketch George Passman Tate

University of Nebraska Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Books in English Digitized Books 1-1-1911 The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch George Passman Tate Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/afghanuno Part of the History Commons, and the International and Area Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tate, George Passman The kingdom of Afghanistan: a historical sketch, with an introductory note by Sir Henry Mortimer Durand. Bombay: "Times of India" Offices, 1911. 224 p., maps This Monograph is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Books at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books in English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tate, G,P. The kfn&ean sf Af&mistan, DATE DUE I Mil 7 (7'8 DEDICATED, BY PERMISSION, HIS EXCELLENCY BARON HARDINGE OF PENSHURST. VICEROY AND GOVERNOR-GENERAL OF INDIA, .a- . (/. BY m HIS OBEDIENT, SERVANT THE AUTHOR. il.IEmtev 01 the Asiniic Society, Be?zg-nl, S?~rueyof I~din. dafhor of 'I Seisinqz : A Menzoir on the FJisio~y,Topo~rcrphj~, A7zliquiiies, (112d Peo$Ie of the Cozi?zt~y''; The F/.o?zlic7,.~ of Baluchisia'nn : Travels on ihe Border.? of Pe~szk n?zd Akhnnistnn " ; " ICalnf : A lMe??zoir on t7ze Cozl7~try and Fnrrzily of the Ahntadsai Khn7zs of Iinlnt" ; 4 ec. \ViTkI AN INrPR<dl>kJCTOl2Y NO'FE PRINTED BY BENNETT COLEMAN & Co., Xc. PUBLISHED AT THE " TIMES OF INDIA" OFFTCES, BOMBAY & C.1LCUTT-4, LONDON AGENCY : gg, SI-IOE LANE, E.C. -

Ajmer-Merwara, Report and Tables, Rajasthan

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1931. VOLUlVIE XXVI . AJMER-MERWARA REPORT AND TABLES. Government of India Pllblica.tions are obtainable from the Government of India Central Publication Branch, 3, Government Place, West, Calcutta, and from the following Agents:- EUROPE- OFFICE OF THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR INDIA, India House, Aldwych, LONDON, W. C. 2. And at all Booksellers. INDIA AND CEYLON: Provincial Book Depots. MADRAS :-Superintendent, Government Press, Mount Road, Madras. BOMBAY :-Superintendent, Government Printing and Stationery, Queen's Road, Bombay. SIND :-Library attached to the Office of the Commissioner in Sind, Karachi. BENGAL; -Bengal Secretariat Book Depot, Writers' Buildings, Room NO.1, Ground Floor, Calcutta. UNITED PROVINCES OF AGRA AND OUDH: -Superintendent of Government Press, United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, Allahahad. ?UNJAB :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Punjab, Lahore. BURMA: - Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, Rangoon. CENTRAL PROVINCES AND BERAR :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Central Province5, Nagpur. ASMM :-Superintendent, Assam Secretariat Press, Shil1ong. BIHAR AND ORISSA :-Superintendent, Government Printing, Bihar and Orissa, P. O. Gulzarbagh, Patna. NORTH.WEST FRONTIER PROVINCE :-Manager, Government Printing and Stationery, Peshawar. Thacker Spink & Co .• Ltd., Calcntta and Simla. *Hossenb.hoy Karimji and Sons, Karachi, W. Newman & Co., Ltd., Calcutta. The Engltsh Bookstall, Karachi. S. K. Lahiri & Co., Calcutta. Rose & Co., Karachi. The Indian School Supply Depot,309, Bow Bazar Street, The Standard Book5tall, Quetta. Calcutta. U. P. Malhotra & Co., Quetta. Butterworth & Co. (India), Ltd., Calcutta. J. Ray and Sons, 43, K. and L., Edwardes Road, M. C. Sarcar & Sons, 15, College Square, Calcutta. Rawalpindi, Murrec and Lahore. Standard Literature Company, Limited, Calcutta. The Standa~d Book De!,!ot, Lahore, NainitaI, Mussoorie, Association Press, Calcutta. -

Indian Oil Corporation Limited Mathura Refinery Mathura Recruitment of Non Executives Advt No: Mr/Hr/Rect(Jea)/1/2016 List of Ca

INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LIMITED MATHURA REFINERY MATHURA RECRUITMENT OF NON EXECUTIVES ADVT NO: MR/HR/RECT(JEA)/1/2016 LIST OF CANDIDATES PROVISIONALLY SHORTLISTED FOR WRITTEN TEST INSTRUCTIONS WRITTEN TEST SHALL BE HELD ON 27th NOVEMBER'2016(SUNDAY) . TEST CENTRE CITY(DELHI/MUMBAI/CHENNAI/KOLKATA), SHALL BE AS PER OPTION GIVEN BY THE CANDIDATE IN THE ONLINE APPLICATION FORM . ONLINE ADMIT CARD FOR WRITTEN TEST, WITH ALL RELEVANT DETAILS SHALL BE AVAILABLE FOR DOWNLOAD ON OUR WEBSITE SHORTLY S.No Discipline Name Registration No Candidate Name Father Name 1 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100002 NITESH SHRIMANT YADAV KARMALKAR SHRIMANT MARUTI YADAV KARMALKAR 2 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100005 ARVIND KUMAR GOPAL VISHWAKARMA 3 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100006 SONU LATE RAGHUNATH CHOUDHARY 4 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100007 ASHISH KUMAR KAUSHAL KISHOR 5 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100010 SHUBHAM GUPTA MANOJ KUMAR GUPTA 6 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100011 LALIT KUMAR HARI OM SHARMA 7 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100012 RAJMANEE GHARBARAN 8 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100013 VIJAY KUMAR HARDUWARI LAL 9 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100014 KRISHNA KUMAR JODHRAJ SINGH 10 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100015 SANDEEP KUMAR DHRU LAL 11 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100016 SONVEER SINGH LILADHAR PRASAD 12 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100017 MUSTAK AHAMAD ALEE MUHAMMAD 13 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100018 KARMPAL SINGH BRAHMDEV SINGH 14 Jr. Engg Asst-IV(Production) - A1 A100019 SHUBHAM JAISWAL VIJAY KUMAR JAISWAL 15 Jr. -

Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia This book offers a fresh approach to the study of religion in modern South Asia. It uses a series of case studies to explore the development of religious ideas and practices, giving students an understanding of the social, politi- cal and historical context. It looks at some familiar themes in the study of religion, such as deity, authoritative texts, myth, worship, teacher traditions and caste, and some of the key ways in which Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam and Sikhism in South Asia have been shaped in the modern period. The book points to the diversity of ways of looking at religious traditions and considers the impact of gender and politics, and the way religion itself is variously understood. Jacqueline Suthren Hirst is Senior Lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of Manchester, UK. Her publications include Sita’s Story and Śaṃkara’s Advaita Vedānta: A Way of Teaching. John Zavos is Senior Lecturer in South Asian Studies at the University of Manchester, UK. He is the author of The Emergence of Hindu Nationalism in India. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 Religious Traditions in Modern South Asia Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:29 24 May 2016 First published 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos The right of Jacqueline Suthren Hirst and John Zavos to be identified as authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abdul in India Adi Dravida in India Population: 35,000 Population: 8,598,000 World Popl: 66,200 World Popl: 8,598,000 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - other People Cluster: South Asia Dalit - other Main Language: Urdu Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.09% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Isudas Source: Dr. Nagaraja Sharma / Shuttersto "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agamudaiyan in India Agamudaiyan Nattaman in India Population: 888,000 Population: 662,000 World Popl: 906,000 World Popl: 670,700 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other People Cluster: South Asia Hindu - other Main Language: Tamil Main Language: Tamil Main Religion: Hinduism Main Religion: Hinduism Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.50% Chr Adherents: 0.19% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Agariya (Hindu traditions) in India Ager (Hindu traditions) -

The Call to North India Why North India?

To The Uttermost Part - The Call To North India The Call to North India Why North India? Sign #1: North India is strategically important in completing<> the unfinished task of world evangelization. Sign #2: Research information on this part of India is<> available as never before. Sign #3: There is a growing sense of vision and cooperation<> in the task. Sign #4: Prayer for North India is being mobilized with a<> new earnestness. Sign #5: Spiritual breakthroughs are occurring all around the area.<> Conclusion: What Can You Do? Prayer Concerns for North India including data about North India major languages, major cities, districts by state, and a list of the unreached people groups in North India. Back to theAD2000 home page Webmaster 7/24/97 http://www.ad2000.org/utermost.htm[24/07/2017 21:29:21] To The Uttermost Part - The Call To North India By his breath the skies became fair; his hand pierced the gliding serpent. And these are but the outer fringe of his works (Job 16:13-14) As I look back over the past six years since the AD2000 & Beyond Movement was launched, several key moments -- "kairos" moments -- stand out in my mind. The first was at the inaugural meeting of our movement in July, 1990, when it was recorded in our minutes that our primary target of concern would be the unevangelized and unreached belt between 10 degrees north and 40 degrees north of the equator and from West Africa to East Asia -- an area of the world we designated the "10/40 Window." The only possible way to reach the people in the 10/40 Window was through concentrated, global, fervent, focused prayer; so we prayed. -

GIPE-208819-Contents.Pdf (10.25Mb)

THE BOOK At the Census of India, in 1881, an attempt was lll3de to obtain the materials for a complete list of all Castes and Tribes as 1 eturned by the. people themselves .and ente red by the Census Enumerators in their Schedutes. Instructions were sent to .each Province and Native State directing that the number of each Caste recorded, .and the composition of each Caste by sex should be shown in the .:final report. In this manner it was designed to lay "a foundation for further research into the little l-nown subject of Caste," a subject .in inquiring into which investigators have been gravelled, not for lack of matter but from its abundance and complexity, and the lack of all rational arran~ment. The subject as a whole has indeed been a mighty maze without a plan. An inquirer .into the social habits and customs of a Caste in nne district h.a.s always been liable to the .subse quent dis.covery that the people whom he had met were but offshoots or wanderers from a larger Tribe whose home was in another province. The distinctive habits and customs of a people are of course always freshest and most marked where the mass of that people dwell : and when a detachment wanders away or splits off from the parent Tribe and settles elsewhere, it suffers, notwithstanding its Caste-conserv ancy. a certain change through the moul ding influence of superior numbers around. Hence the desideratum of a bird'.s-eye view of the entire system of Castes and Tribes found in India : and this, as far as tlteir strength and distribution go, is what 1 have tried to supply in this Compendium. -

Evolution of Rural Settlements and Their Spatial Variations in Meerut District

EVOLUTION OF RURAL SETTLEMENTS AND THEIR SPATIAL VARIATIONS IN MEERUT DISTRICT 5^BSTRACT ^ 0 THESIS •\. f*f i;,-^-- SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Bottar of ^iitloifoplip \ I 'Zy- •.'.•.•"•.. IN -I , ^ I <:•*- ^^-X. - •^<:<« A ..^.,^^^BV GHAZALA HAiMEED Under the Supervision of DR. ATEEQUE AHMAD DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2000 ABSTRACT Settlement has occupied an important place among the visual imprints made by man upon physical landscape, through the process of cultural occupancy since the dawn of civilization. The evolution and growth of settlement in an area is a result of interplay of the prevailing ecological conditions, cultural and social values of the residents, technology, management system and the settling process through time spans settlement refers to an organized colony of human beings ranging from a simple farmstead to a highly complex city and from a temporary camp of hunters or miners to more sedentary houses of farmers and city dwellers. Settlement includes not only the various kinds of buildings put to a variety of uses but also lanes, streets, roads, parks, places of worship and play grounds etc. In the initial stages settlement features bear simple forms and have close relationship with the environment. However, the growth of knowledge and spread of civilization increases the degree of variability in their form and size. The problem of human settlements has emerged as one of the most challenging issues particularly in the under developed countries of the world. About 65 per cent of the world's population still lives in rural areas. Since the country is dominated by agrarian economy and most of the population is concentrated in villages, the study of rural settlements in India should be given prime importance. -

REGISTER PART-A.Xlsx

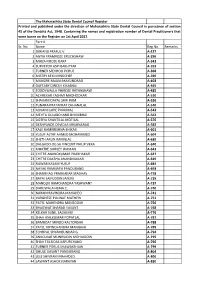

The Maharashtra State Dental Council Register Printed and published under the direction of Maharashtra State Dental Council in pursuance of section 45 of the Dentsits Act, 1948. Containing the names and registration number of Dental Practitioners that were borne on the Register on 1st April 2017. Part-A Sr. No. Name Reg.No. Remarks 1 DIWANJI PRAFUL V. A-227 2 ANTIA FRAMROZE ERUCHSHAW A-296 3 MIRZA FIROZE DARA A-343 4 SURVEYOR ASPI BAKHTYAR A-352 5 TURNER MEHROO PORUS A-368 6 MISTRY KEKI MINOCHER A-396 7 MUNGRE RAJANI MAKUNDRAO A-403 8 DAFTARY DINESH KIKABHAI A-465 9 TODDYWALLA PHIROZE RATANSHAW A-485 10 ACHREKAR YASHMI MADHOOKAR A-510 11 SHAHANI DAYAL SHRI RAM A-526 12 TUNARA PRATAPRAY CHHANALAL A-540 13 ADVANI GOPE PARUMAL A-543 14 MEHTA GULABCHAND BHMJIBHAI A-562 15 DOTIYA SHANTILAL MOTILAL A-576 16 DESHPANDE DEVIDAS KRISHNARAO A-582 17 KALE RAMKRISHNA BHIKAJI A-601 18 YUSUF ALTAF AHMED MOHAMMED A-604 19 SHETH ARUN RAMNLAL A-639 20 DALGADO-DE-SA VINCENT PHILIP VERA A-640 21 MHATRE SHIRLEY WAMAN A-642 22 CHITRE ANANDKUMAR PRABHAKAR A-647 23 CHITRE DAKSHA ANANDKUMAR A-649 24 NAWAB KASAM YUSUF A-684 25 NAYAK RAMNATH PANDURANG A-693 26 SHANBHAG PRABHAKAR MADHAV A-718 27 BAPAI SAIFUDDIN JAFERJI A-729 28 MANDLIK RAMCHANDRA YASHWANT A-737 29 DARUWALA HEMA C. A-740 30 NARAIN RAVINDRA MAHADEO A-741 31 VARGHESE PULINAT MATHEW A-751 32 PATEL MAHENDRA MANSOOKH A-756 33 BHAGWAT SHARAD VASANT A-768 34 KELKAR SUNIL SADASHIV A-776 35 SHAH ANILKUMAR POPATLAL A-787 36 BAMBOAT MINOO RALTONSHA A-788 37 PATEL VIPINCHANDRA MANIBHAI A-789 38 ECHHPAL SHYAMSUNDAR G. -

IMMIGRATION LAW REPORTER Fourth Series/Quatri`Eme S´Erie Recueil De Jurisprudence En Droit De L’Immigration VOLUME 18 (Cited 18 Imm

IMMIGRATION LAW REPORTER Fourth Series/Quatri`eme s´erie Recueil de jurisprudence en droit de l’immigration VOLUME 18 (Cited 18 Imm. L.R. (4th)) EDITORS-IN-CHIEF/REDACTEURS´ EN CHEF Cecil L. Rotenberg, Q.C. Mario D. Bellissimo, LL.B. Barrister & Solicitor Bellissimo Law Group Don Mills, Ontario Toronto, Ontario Certified Specialist Certified Specialist ASSOCIATE EDITOR/REDACTEUR´ ADJOINT Randolph Hahn, D.PHIL.(OXON), LL.B. Guberman, Garson Toronto, Ontario Certified Specialist CARSWELL EDITORIAL STAFF/REDACTION´ DE CARSWELL Cheryl L. McPherson, B.A.(HONS.) Director, Primary Content Operations Directrice des activit´es li´ees au contenu principal Andre Popadynec, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Product Development Manager Nicole Ross, B.A., LL.B. Andrea Andrulis, B.A., LL.B., LL.M. Supervisor, Legal Writing (Acting) Supervisor, Legal Writing Peter Bondy, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Heather Stone, B.A., LL.B. Lead Legal Writer Lead Legal Writer Rachel Bernstein, B.A.(HONS.), J.D. Peggy Gibbons, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Legal Writer Senior Legal Writer Jim Fitch, B.A., LL.B. Stephanie Hanna, B.A., M.A., LL.B. Senior Legal Writer Senior Legal Writer Mark Koskie, B.A.(HONS.), M.A., LL.B. Amanda Stewart, B.A.(HONS.), LL.B. Legal Writer Senior Legal Writer Martin-Fran¸cois Parent, LL.B., LL.M., Heather Niziol, B.A. DEA (PARIS II) Content Editor Bilingual Legal Writer IMMIGRATION LAW REPORTER, a national series of topical law reports, Recueil de jurisprudence en droit de l’immigration, une s´erie nationale de is published twelve times per year. Subscription rate $398 per bound volume recueils de jurisprudence sp´ecialis´ee, est publi´e 12 fois par anne´e.