University of Hawaii' Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Party Formation and Political Legitimacy

THE EVOLUTION OF HEZBOLLAH: PARTY FORMATION AND POLITICAL LEGITIMACY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science at George Mason University, and the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Malta By Anastasia Franjie Bachelor of Arts George Mason University, 2011 Director: Lourdes Pullicino, Lecturer Mediterranean Academy of Diplomatic Studies Fall Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to several individuals whom were of great help and positive influence in my life. To my parents, Serge and Anna Maria whom were advocates of my pursuing higher education, and gave me the ability to experience and be part of a unique cultural upbringing, To my siblings Alexander, Grace, Olivia, Kristel, and our princess Mia, showing them that continuous success requires hard work, To my Maltese family whom stood by me through this process and pushed me to be over the average, Finally and most importantly to my Lebanon and every oppressed around the world with hopes of achieving peace, security and justice. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS During the course of pursuing my dual master degree from the University of Malta and George Mason University in Valletta, Malta, I had the strongest support from my family whom were overseas. This experience not only taught me about conflict analysis and resolution and Mediterranean security but it also taught me about responsibility, and life. Therefore, I would like to thank the many friends, relatives, and supporters who have made this happen. -

Saudi Arabia, Iran and De-Escalation in the Persian Gulf

Saudi Arabia, Iran and De-Escalation in the Persian Gulf Contents Acknowledgements About the authors Introduction 1. Simon Mabon and Edward Wastnidge, Saudi Arabia and Iran: Resilient Rivalries and Pragmatic Possibilities 2. Cinzia Bianco, KSA-Iran rivalry: an analysis of Saudi strategic calculus 3. Shahram Akbarzadeh, Iran-Hizbullah ‘Proxy’ Relations 4. Lawrence Rubin, Saudi Arabia, Iran and the United States 5. Clive Jones, A Chimera of Rapprochement: Iran and the Gulf Monarchies: The View from Israel 6. Banafsheh Keynoush, Prospects for Talks between Iran and Saudi Arabia 7. Robert Mason, Towards Peace Building in Saudi-Iranian Relations 8. Sukru Cildir, OPEC as a Site of De-Escalation? 9. Ibrahim Fraihat, Reconciliation: Saudi Arabia and Iran 10. Kristian Coates Ulrichsen, Diplomacy and de-escalation in the Persian Gulf 11. Eyad Al Refai and Samira Nasirzadeh, Saudi Arabia and Iran: How our two countries could make peace and bring stability to the Middle East. Concluding Remarks Acknowledgements SEPAD has been generously funded by Carnegie Corporation of New York. We would like to extend thanks to Hillary Weisner and Nehal Amer for their continuous support in all ways imaginable. We would also like to thank all those who contributed pieces to this report. This was undertaken during the formative stages of the COVID19 pandemic and we are grateful that authors were able to offer contributions on this important topic at a time when they were facing myriad other pressures and demands on their time; thank you. We would also like to thank Elias Ghazal for his editorial and technological support. About the Authors Shahram Akbarzadeh is Research Professor of Middle East and Central Asian Politics at Deakin University. -

TERRORIST TRIALS: a Report Card

A P U B L I C A T I O N O F T H E C E N T E R O N L A W A N D S E C U R I T Y A T N Y U S C H O O L O F L A W | F E B R U A R Y 2 0 0 5 110 W E S T T H I R D S T R E E T , N E W Y O R K , N Y 10 0 12 | W W W . L A W . N Y U . E D U / C E N T E R S / L A W S E C U R I T Y TERRORIST TRIALS: A Report Card hen he announced his resignation in November 2004, Attorney General John Ashcroft declared, “The objective of securing the safety of Americans W from crime and terror has been achieved.” He was referring to that part of the war for which he was largely respo n s i b l e : the legal and judicial record. Ei g h t e e n months prior to that, in testimony before Congress, Ashcroft summed up the pretrial, interim results of his war on terror. Ashcroft cited 18,000 subpoenas, 211 criminal charges, 47 8 [As a preliminary note to the findings, it is important to point deportations and $124 million in frozen assets. Looking to out that accurate and comprehensive information was almost document the results of these efforts, represented in the prose- impossible to obtain. -

Darwich2015.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Ideational and Material Forces in Threat Perception Saudi and Syrian Choices in Middle East Wars May Darwich PhD The University of Edinburgh 2015 1 2 Declaration I declare that this thesis is of my own composition with acknowledgement of other sources, and that it has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. May Darwich 3 4 Abstract How do states perceive threats? Why are material forces sometimes more prominent in shaping threat perception, whereas ideational ones are key in other instances? This study aims to move beyond the task of determining whether material or ideational factors offer a more plausible explanation by arguing that threat perception is a function of the interplay between material factors and state identity, the influence of which can run both ways. -

30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker Mcneill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman

No. 2405 April 29, 2010 30 Terrorist Plots Foiled: How the System Worked Jena Baker McNeill, James Jay Carafano, Ph.D., and Jessica Zuckerman Abstract: In 2009 alone, U.S. authorities foiled at least six terrorist plots against the United States. Since Septem- ber 11, 2001, at least 30 planned terrorist attacks have Talking Points been foiled, all but two of them prevented by law enforce- • At least 30 terrorist plots against the United ment. The two notable exceptions are the passengers and States have been foiled since 9/11. It is clear flight attendants who subdued the “shoe bomber” in 2001 that terrorists continue to wage war against and the “underwear bomber” on Christmas Day in 2009. America. Bottom line: The system has generally worked well. But • President Obama spent his first year and a half many tools necessary for ferreting out conspiracies and in office dismantling many of the counterter- catching terrorists are under attack. Chief among them are rorism tools that have kept Americans safer, key provisions of the PATRIOT Act that are set to expire at including his decision to prosecute foreign ter- the end of this year. It is time for President Obama to dem- rorists in U.S. civilian courts, dismantlement of onstrate his commitment to keeping the country safe. Her- the CIA’s interrogation abilities, lackadaisical itage Foundation national security experts provide a road support for the PATRIOT Act, and an attempt map for a successful counterterrorism strategy. to shut down Guantanamo Bay. • The counterterrorism system that has worked successfully in the past must be pre- served in order for the nation to be successful In 2009, at least six planned terrorist plots against in fighting terrorists in the future. -

Homeland Security Implications of Radicalization

THE HOMELAND SECURITY IMPLICATIONS OF RADICALIZATION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT OF THE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION SEPTEMBER 20, 2006 Serial No. 109–104 Printed for the use of the Committee on Homeland Security Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 35–626 PDF WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman DON YOUNG, Alaska BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas LORETTA SANCHEZ, California CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut NORMAN D. DICKS, Washington JOHN LINDER, Georgia JANE HARMAN, California MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana PETER A. DEFAZIO, Oregon TOM DAVIS, Virginia NITA M. LOWEY, New York DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California ELEANOR HOLMES NORTON, District of JIM GIBBONS, Nevada Columbia ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut ZOE LOFGREN, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON-LEE, Texas STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico BILL PASCRELL, JR., New Jersey KATHERINE HARRIS, Florida DONNA M. CHRISTENSEN, U.S. Virgin Islands BOBBY JINDAL, Louisiana BOB ETHERIDGE, North Carolina DAVE G. REICHERT, Washington JAMES R. LANGEVIN, Rhode Island MICHAEL MCCAUL, Texas KENDRICK B. MEEK, Florida CHARLIE DENT, Pennsylvania GINNY BROWN-WAITE, Florida SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE, INFORMATION SHARING, AND TERRORISM RISK ASSESSMENT ROB SIMMONS, Connecticut, Chairman CURT WELDON, Pennsylvania ZOE LOFGREN, California MARK E. -

The Ideological Transformation of Hezbollah Since Its Involvement in the Syrian Civil War : Local Perspectives and Foreign Observations

The Ideological Transformation of Hezbollah Since its Involvement in the Syrian Civil War : Local Perspectives and Foreign Observations Mémoire Ian Mac Donald Maîtrise en science politique - avec mémoire Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Ian Mac Donald, 2020 Introduction Political and social movements use ideology as a method of justifying, interpreting, and challenging the surrounding social-political order (McAdam, Doug, et al., 1996). The success with which a social or political movement constructs and expresses the set of explanatory and normative beliefs and assumptions that make up its ideology can often translate into its competitive advantage over contending movements. In the modern nation-state, nationalist ideology, where nations are “imagined communities,” according to Benedict Anderson, is the most common form of political ideology that fabricates a collective intersubjective identity for a population and legitimates groups’ power. However, in Lebanon, sectarianism, where political ideology is tied to a specific religious community, is also a compelling narrative that has so often characterized the ideology of the myriad actors in Lebanese state and society. In the Lebanese political realm, sectarian and nationalist ideologies of organizations and movements both blend and compete with each other as elites vie for political power over populations. Authors of sectarianism often take a constructivist and instrumentalist approach in explaining the ideological power of sectarianism in Lebanon: Just as history demonstrates state leaders’ use of nationalist fervour in the pursuit of political power, sectarianism is also an ideology in which elites can play a manipulative role and exploit the religious identity of populations in order to further their own political goals (Cammett, 2014; Haddad, 2011; Salloukh, Barakat, Al-Habbal, Khattab, & Mikaelian, 2015; Wehrey, 2018). -

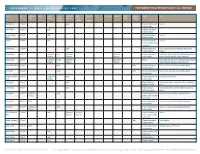

Terrorist Trial Report Card: U.S. Edition – Appendix B

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 TERRORIST TRIAL REPORT CARD: U.S. EDITION Name Date Commercial Drugs General General Immigration National Obstruction Other Racketeering Terrorism Violent Weapons Sentence Notes Fraud Fraud Criminal Violations Security of Crimes Violations Conspiracy Violations Investigation Khalid Al Draibi 12-Sep-01 Guilty 4 months imprisonment, 36 Deported months probation Sherif Khamis 13-Sep-01 Guilty 2.5 months imprisonment, 36 months probation Jean-Tony Antoine 14-Sep-01 Guilty 12 months imprisonment, Deported Oulai 24 months probation Atif Raza 17-Sep-01 Guilty 4.7 months imprisonment, Deported 36 months probation, $4,183 fine/restitution Francis Guagni 17-Sep-01 Guilty 20 months imprisonment, French national arrested at Canadian border with box cutter; 36 months probation Deported Ahmed Hannan 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Guilty Acquitted or Acquitted or 6 months imprisonment, 24 Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed months probation Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Karim Koubriti 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Pending Acquitted or Acquitted or Pending Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Vincente Rafael Pierre 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 24 months imprisonment, Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, Traci Elaine Upshur) 36 months probation Traci Upshur 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 15 months imprisonment, 24 Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, -

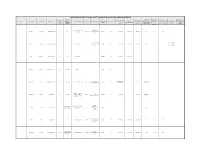

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no. -

Hezbollah: Armed Resistance to Political Participation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2014-06 Hezbollah: armed resistance to political participation Morrissey, Colin J. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/42690 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS HEZBOLLAH: ARMED RESISTANCE TO POLITICAL PARTICIPATION by Colin J. Morrissey June 2014 Thesis Advisor: Anne Marie Baylouny Second Reader: Tristan Mabry Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2014 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS HEZBOLLAH: ARMED RESISTANCE TO POLITICAL PARTICIPATION 6. AUTHOR(S) Colin J. Morrissey 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943-5000 9.