Architecture's Appearance and the Practices of Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctoral Program in Architectural Composition

36 landscapes and architectural expression. of the first semester, in consultation with the DOCTORAL PROGRAM The second and third phase involve training supervisor. During the following five semesters, experience abroad, with participation in seminars the thesis is developed as other studies are carried IN ARCHITECTURAL COMPOSITION and research with which the doctoral candidate out, taking on a progressively more important role. is establishing relationships. The thesis is understood as research and must be characterised by cultural and scientific originality. Doctoral thesis It may or may not have a design aspect. The | 2011 PhD Yearbook Maximum importance is given to the doctoral doctoral candidate is required to report regularly thesis. It constitutes the core and the conclusion on the progress of the thesis and to attend open of the doctoral candidate’s study and is attributed sessions, held in the presence of the teaching staff 37 The doctoral program is understood as advanced learning, rooted in a very large number of credits. The theme and and the other doctoral candidates, at which the Chair: the history of the architect’s craft, of the profession and of the wealth the formulation must be defined before the end thesis is discussed. Prof. Daniele Vitale of architectural techniques. The objective is to train architects who are capable professionals from a general point of view, with solid historical/humanistic training and a strong theoretical base, but who Doctoral PROGRAM Board also have extensive knowledge of town planning and construction techniques and who are able to carry out architectural design. The Marco Biraghi Marco Dezzi Bardeschi Attilio Pracchi training consists of the imparting of organised contents, the sharing Salvatore Bisogni Carolina Di Biase Marco Prusicki of research, and participation in cultural debate. -

Ejournals @ Oklahoma State University Library

ENIGMA AS MORAL REQUIREMENT IN THE WAKE OF LEDOUX’S WORK: AUTONOMY AND EXPRESSION IN ARCHITECTURE ALBERTO RUBIO GARRIDO Architecture’s alleged capacity to meet ever new cultural and social challenges raises the dilemma between considering architecture a modern art or Purity, the a vehicle for the realization of social good. The absolute, nature of the dilemma and its potential resolution “ in favor of the preservation of architecture’s artistic perfection, [...] autonomy are this paper’s two leading concerns. To pursue them we first need to get clearer what continue to be renders art ‘autonomous’. understood by As a concept, autonomy defies easy definition. It acquired multiple meanings in the history of reference to ideas and frequently appeared under various guises, art’s struggle especially throughout the nineteenth century. Purity, the absolute, perfection, freedom, self- for autonomy. determination, l’art pour l’art, futility, and more: ” such notions were, and continue to be, understood by reference to art’s struggle for autonomy. Yet our understanding of that struggle, indeed of art’s autonomy, remains contested.1 On the face of it, ‘autonomy’ designates a thing’s (or someone’s) independence when determining its own laws. Such laws, we shall see, can range over the ontological, the ethical, and even the aesthetic. Autonomy expresses the fundamental modern principle of something’s giving itself its own laws and setting its own ends. If this minimal gloss is correct, its application to architecture requires clarification and defense right away. Architecture as, or insofar as it is, a particular isparchitecture.com art faces external constraints and limits on its autonomy; limits it cannot evade. -

Von Ledoux Bis Le Corbusier 110

CUADERNO DE NOTAS 15 - 2014 ARTÍCULOS VON LEDOUX BIS LE CORBUSIER 110 Macarena Reconsidering Emil Kaufmann’s de la Vega Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier El objetivo de este ensayo es re-abrir y re-leer Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier de Emil Kaufmann. A pesar de que Panayotis Tournikiotis y Anthony Vidler lo incluyeran en sus respectivos discursos sobre la historiografía de la arquitectura moderna, se pro- pone reconsiderar a su autor como un historiador pionero de la Ilustración. Tres ideas: el único protagonista del libro es Claude-Nicolas Ledoux; la arquitectura en torno a 1800 necesitaba una reevaluación; y la obra de Kaufmann se enmarca en un tiempo de búsqueda de una nueva ciencia del arte y una nueva historia de la arqui- tectura. Kaufmann es una figura de transición entre una generación previa de histo- riadores del arte que establecieron conceptos y principios fundamentales, y otros de su misma generación que se embarcaron en la tarea de considerar la arquitectura moderna como objeto de una investigación histórica. Emil Kaufmann’s an Emil Kaufmann’s Von Ledoux bis Le Von Ledoux bis Le CCorbusier be considered a history of Corbusier: Ursprung modern architecture? Contrary to what und Entwicklung der certain theorists have proposed in their autonomen Architektur, 1933. works, this research aims to re-open and (Tournikiotis [2014]) re-read Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier: Ursprung und Entwicklung der auntono- men Architektur in order to reconsider Kaufmann as a pioneer historian of the Age of Reason, rather than a historian of modern architecture. On the one hand, Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier is discussed in two studies: first, in Panayotis Tournikiotis’ The Historio- graphy of Modern Architecture published in 1999; and second, in Anthony Vidler’s Histories of the Immediate Present publis- hed in 2008. -

Thinking in Architecture

HGJLH9Qz >AFD9F<= )*/1+, HGKLAGQB 9J;@AL=;LMJ=<=KA?F9JL Yj[`al][lmj] &(0 &(0 JYfYd\DYoj]f[]:mad\af_gfl`]@gjargf&L`]9j[`al][lmj]g^Kn]jj]>]`f Q=9J:GGC h`glg_jYh`q LaegNYdbYccY@]Y\afl`][dgm\k$^]]lgfl`]_jgmf\ &(0 ]p`aZalagfk =dafYH]fllaf]fO`Yl\g_Yj\]faf_$l`]EYljqgk`cY\gddYf\l`]Jgddaf_Klgf]k`Yn]af[geegf7 ÇKhYlaYdh]jkh][lan]kgfl`];Yjf]_a]9jl9oYj\*((0]p`aZalagf LaegNYdbYccYGdd]:µjldaf_Ìk\j]Yekg^kl]]d Zggck HYfmD]`lgnmgjaL`]JakcYf\Dmpmjqg^HmZda[MjZYfKhY[] d][lmj]k 9f\j]oEY[EaddYf;`Yjd]kJ]ffa]EY[caflgk`&@ak[gfljaZmlagflgl`]Eg\]jfEgn]e]fl D]kda]NYf<mr]j9\gd^DggkJ]Y\qeY\] =nY=jackkgfOal`@aklgjqLgoYj\kEg\]jfalq&L`]9j[`al][lmj]g^?mffYj9khdmf\ hlY`oYkl`]Yf[a]fl=_qhlaYf_g\ g^Zmad\af_$o`gk]aeY_]YdkgY\gjfk l`]ZY[chY_]g^gmjhmZda[Ylagf& ;gn]j HL9@ Hjg_jk$L [`faim]$9j[`al][lmj] H]jllaC]cYjYaf]f&LadY HYkkY_]+!$*((/$[%hjafl\aYk][$)1-p)*-[e$\]lYad& @]dkafca!oYkYko]ddl`]fYe]g^l`] EMK=MEG>;GFL=EHGJ9JQ9JLCA9KE9& >affak`;A9E_jgmh^gmf\]\af)1-+ ZqH]flla9`gdY$9mdak:dgekl]\l$ 9Yjf]=jnaYf\AdeYjaLYhagnYYjY& AKKF)*+1%+,() &(0 = < A L G J A 9 D ((- YdnYjYYdlgY[Y\]eq HYjlg^l`]9dnYj9Ydlg>gmf\Ylagf$l`]9dnYj9Ydlg9[Y\]eqakhjaeYjadq^mf\]\Zq &(0 l`]>affak`Eafakljqg^=\m[YlagfYf\akdg[Yl]\YlKlm\ag9YdlgafLaadaeca$@]dkafca& L`]9[Y\]eqYdkgjYak]k^mf\af_gfYhjgb][lZYkak3YeYbgjhYjlf]j`YkZ]]fl`];alqg^Bqnkcqd& L`]Jmd]kYf\J]_mdYlagfkg^l`]9[Y\]eqkh][a^qalk^mf\Ye]flYdhmjhgk]kYkk]jnaf_ `llh2''ooo&YdnYjYYdlg&Õ YkY\ak[mkkagf^gjme^gjafl]jfYlagfYd]fnajgfe]flYd[mdlmj]$hYjla[mdYjdq[gfl]ehgjYjqYj[`al][lmj]$ Laadaeca*($((++(@]dkafca$>afdYf\ Yf\YkY[gddYZgjYlan]gj_Yf^gj[gflafmaf_]\m[YlagfafYj[`al][lmj]& -

Three Revolutionary Architects: Boullee, Ledoux, and Lequeu

TRANSACTIONS OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY HELD AT PHILA DELPHIA FO R PROMO TING USEF UL KNO WLEDGE NEW SERIES-VOLUME 42, PART 3 1952 THREE REVOLUTIONARY ARCHITECTS, BOULLEE, LEDOUX, AND LEQUEU EMIL KAUFMANN THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY INDEPENDENCE SQU ARE PHILADELPHIA 6 OCTOBER, 1952 COPYRIGHT 1952 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY PREFACE 1 am deeply indebted to the American Philosophical Columbia University, Prof. Talbot F. Hamlin, Prof. Society for having made possible the completion of this James Grote Van Derpool; Mr. Adolf Placzek, Avery study by its generous grants. 1 wish also to express my Library, and Miss Ruth Cook, librarian of the Archi sincere gratitude to those who helped me in various ways tectural Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. in the preparation of this book, above all to M. Jean For permission to reproduce drawings and photo Adhemar, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, Dr. Leo C. graphs 1 am indebted to the Cabinet d'Estampes, Bibl. Collins, New York City, Prof. Donald Drew Egbert, Nationale, Paris (drawings of Boullee and Lequeu), Princeton University, Prof. Paul Frankl, Inst. for Ad Archives photographiques, Paris (Hotel Brunoy), Bal vanced Study, Princeton, Prof. Julius S. Held, Colum timore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Md. (portrait of bia University, New York, Architect Philip Johnson, Ledoux), Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Deco Museum of Modern Art, New York, Prof. Erwin ration, New York (etchings by Le Geay). Panofsky, Inst. for Advanced Study, Princeton, Prof. The quotations are in the original orthography. The Meyer Schapiro, Columbia University, New York, Prof. bibliographical references conform with the abbrevia John Shapley, Catholic University of America, Wash tions of the World List of Historical Periodicals, Ox ington, D. -

Pdf (Accessed August 26, 2020)

Disgust is an affect rarely associated with the discipline of art history. To read Hans Sedlmayr’s 1948 book Verlust der Mitte (literally, “Loss of the center,” but published in English as Art in Crisis: The Lost Center) is to confront a vast vocabulary of abhorrence. In the book’s counter-Enlightenment history of European art from the French Revolution to the 1930s, Sedlmayr proposes a bile-soaked theory of modernism characterized as an “ally of anarchy” driven by a “hatred of the human race,” a succession of “artistic abortions” and “symptoms of extreme degeneration,” adding up to a “chaos of total decay” (and this all on a single page). Yet, his splenetic contempt for romanticism, abstraction, rationalist architecture, Surrealist automatism, and so on is directed not so much at the artists as at the world that made their work possible. In one passage, Sedlmayr offers a bitter “defense of the extremists,” noting that the apparent rejection of realism in modern art was in fact “realistic” in its “spiritual and moral portrait of man,” accurately reflecting a humanity dissolving into the madness of the masses, lapsing into racialized “primitivism,” and worshiping its own illusory autonomy.1 Sedlmayr’s monstrosity, however, lies not in his anguish over the dissonance between the history of art and his own political commitments but in his period of optimism about their reconciliation.2 Following his studies with Max Dvořák and Julius von Schlosser, Sedlmayr developed in the late 1920s and 1930s a mode of Strukturanalyse (structural analysis) of art that sought to make good on the promises of Alois Riegl’s method, writing pioneering and controversial essays on baroque art and architecture.3 Concurrently, while living in Vienna, 1 Hans Sedlmayr, Art in Crisis: The Lost Center, trans. -

Histories of the Immediate Present : Inventing Architectural Modernism / Anthony Vidler

THE MIT PRESS CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS LONDON, ENGLAND HISTORIES OF THE IMMEDIATE PRESENT INVENTING ARCHITECTURAL MODERNISM ANTHONY VIDLER © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Filosofi a by Graphic Composition, Inc. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vidler, Anthony. Histories of the immediate present : inventing architectural modernism / Anthony Vidler. p. cm. — (Writing architecture) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-72051-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modern movement (Architecture) 2. Architecture— Historiography. 3. Architectural criticism—Europe—History— 20th century. I. Title. NA682.M63V53 2008 724'.6—dc22 2007020845 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS FOREWORD: [BRACKET]ING HISTORY by Peter Eisenman vii PREFACE xiii INTRODUCTION 1 1 NEOCLASSICAL MODERNISM: EMIL KAUFMANN 17 Autonomy 17 Neoclassicism and Autonomy 21 From Kant to Le Corbusier 32 Structural Analysis 41 From Kaufmann to Johnson and Rossi 52 Autonomy Revived 58 2 MANNERIST MODERNISM: -

3Rd Ahau International Congress

3rd AhAU International Congress Madrid, 18-19 November 2021 BUILT AND THOUGHT GIORGIO VASARI / JOHANN BERNHARD FISCHER VON ERLACH / JOHANN JOACHIM WINCKELMANN / EUGENIO LLAGUNO Y AMÍROLA / ANTONIO PONZ / GASPAR MELCHOR DE JOVELLANOS / ISIDORO BOSARTE / JUAN AGUSTÍN CEÁN BERMÚDEZ / JUAN MIGUEL INCLÁN VALDÉS / JOSÉ CAVEDA Y NAVA / GOTTFRIED SEMPER / KARL BÖTTICHER / JAMES FERGUSSON / EUGÈNE-EMMANUEL VIOLLET-LE-DUC / PEDRO DE MADRAZO / JOSÉ AMADOR DE LOS RÍOS / GEORGE EDMUND STREET / JUAN FACUNDO RIAÑO / JOSEPH DURM / AUGUSTE CHOISY / OTTO SCHUBERT / ALOIS RIEGL / VICENTE LAMPÉREZ / HEINRICH WÖLFFLIN / BANISTER FLETCHER / ABY WARBURG / JOSEP PUIG I CADAFALCH / MANUEL GÓMEZ-MORENO MARTÍNEZ / PAUL FRANKL / HENRI FOCILLON / JOSEP PIJOAN / WILHELM WORRINGER / GEOFFREY SCOTT / ADOLF BEHNE / SIGFRIED GIEDION / LEOPOLDO TORRES BALBÁS / JOSEP FRANCESC RÀFOLS / EMIL KAUFMANN / ANDRÉS CALZADA / ERWIN PANOFSKY / CAROLA GIEDION-WELCKER / KENNETH JOHN CONANT / HANS SEDLMAYR / RICHARD KRAUTHEIMER / ROBERTO PANE / STEEN EILER RASMUSSEN / HÉCTOR VELARDE / CHARLES DE TOLNAY / PIERRE FRANCASTEL / FRANCISCO ÍÑIGUEZ ALMECH / RUDOLF WITTKOWER / MARIO J. BUSCHIAZZO / NIKOLAUS PEVSNER / BERNARD BEVAN / HENRY-RUSSELL HITCHCOCK / SIBYL MOHOLY-NAGY / JULIUS POSENER / MEYER SCHAPIRO / JOHN SUMMERSON / ANTHONY BLUNT / GIULIO CARLO ARGAN / ERNST GOMBRICH / FERNANDO CHUECA GOITIA / ANDRÉ CHASTEL / GEORGE KUBLER / ALEXANDRE CIRICI PELLICER / DAMIÁN BAYÓN / JOSEP MARIA SOSTRES / RENÉ TAYLOR / GEORGE R. COLLINS / BRUNO ZEVI / JAMES S. ACKERMAN / PETER COLLINS / COLIN ROWE -

The Vienna School of Art History and (Viennese) Modern Architecture

The Vienna School of Art History and (Viennese) Modern Architecture Jindřich Vybíral In scholarly literature on the historiography of modern architecture, the Viennese School primarily appears as the institution that had educated Emil Kaufmann (1891–1953), the author of Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier, one of the most famous ‘genealogies’ of the Modernist movement.1 As is well known, Kaufmann was a pupil of Max Dvořák and Josef Strzygowski – it was under Dvořák’s tuition that Kaufmann defended his 1920 PhD dissertation on ‘Ledoux’s architectonic projects and Classicist aesthetics’2 – and the methodological principles of the Viennese school were pivotal for his analyses even after he left Austria and settled down in the United States.3 Modern architecture was also among the interests of another Dvořák's student, Dagobert Frey (1883–1962), who took over the editorship of Der Architekt in 1919 and consequently published a number of important essays on the topic in this journal.4 However, the topic of my paper is the work done on modern architecture by ‘teachers’ – the classics of the ‘older Viennese school’ – rather than their pupils. And my focus will be even more limited than that. At the time when the personality of Alois Riegl shone forth at the University of Vienna and then ‘disappeared like a comet’5, the capital of the Hapsburg monarchy represented one of the most energetic centres of architectural modernism in Europe – primarily due to Otto Wagner (1841-1918) and his followers from the ‘special school’ of architecture at the Academy of Arts. To compare the roles of the two schools appears highly plausible even without postulating any coherence postulate a la Hegel or believing in an unconscious connection between parallel phenomena. -

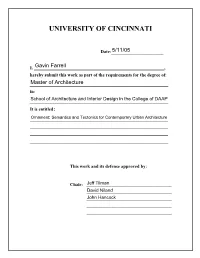

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Ornament: Semantics and Tectonics for Contemporary Urban Architecture A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE In the school of Architecture and Interior Design of the College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning (DAAP) 2005 by Gavin R. Farrell B.S. Arch, University of Cincinnati, 2003 Committee chairs: Jeff Tilman David Niland John Hancock i Abstract ____________________________________________________________ With some notable exceptions, ornament today has largely increased its scale and reduced its descriptive content in what can only be described as an evasion of putting forward a readable socially-relevant meaning. It may be that current sentiments of a diverse, relativistic modern society prevent ornament’s conveyance of direct idealistic social messages. If this is so, then ornament has two ‘holding patterns;’ 1. To express the purpose of the building, and 2. to increase the building’s significance. The theoretical root of the problem of ornament will be investigated, and its various types and methods of application will be described with an eye for giving an understanding of ornament’s strengths, weaknesses, and its intimate, mutually-enhancing connection with form, structure, and the resultant space. Tentative principles of use for the 21st century will be developed, suggesting the necessity of a real or implied relationship between tectonics and semantics. -

Designing Thinking

". building designing thinking Stanford Anduson is a registered architect and Professor of HIstory and Architecture in the Department of Architecture at the Massachusetts Institute Df Technology, Cambridge, MaSsachusetts, where he has taught since 1963 Hew-founded and directed MIT's pioneering PhD program In History, Theory and Criticism of Ar~ Archite(;ture, and STANFORD ANDERSON Urban Form from 1974 to 1991 He served as Head of the Department THINKING IN ARCHITECTURE of Architecture from 1991 to 1005. Anderson was educated in architecture at the Universities of Minnesota and California, bbe Laugier's claim that "in those arts which are not purely mechanical and holdsa PhD in historyof art it is not sufficient to know how to work; it is above all important to learn from Columbia University in New to think" But how should one think about architecture, or rather, think in York City He was the 2004 AlAI A ACSA Topaz laureate, the highest architecture? Is there a specific architectural way of thinking? .., Can a design be a American award in arctutecturat form of thinking? Or does it all boil down to subjective taste? education. Anderson's research and writing concern architectural theory, modern architecture in "Not subjective taste!" - we had better say, if we think there is a discipline Europe and America, American of architecture, a profession of architecture; if we can honourably have urbenbmand epistemology and historiography Anderson schools of architecture or be professors or crtucs of architecture. translated and wrote the lruroduc- Abbe Laugier put his question with reference to "arts which are not tory essay for Hermann Muthesius: purely mechanical," among which he counted architecture. -

Con GEORG GOTTFRIED DEHIO ALOIS RIEGL Y MAX DVORÁK

con GEORG GOTTFRIED DEHIO ALOIS RIEGL Y MAX DVORÁK REVISTA DE CONSERVACIÓN NÚM. 5 JULIO 2018 ISSN: 2395-9479 con GEORG GOTTFRIED DEHIO ALOIS RIEGL Y MAX DVORÁK SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA María Cristina García Cepeda Editor Científico Secretaria de Cultura Valerie Magar Meurs INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ANTROPOLOGÍA E HISTORIA Consejo Editorial Valerie Magar Meurs Diego Prieto Hernández Renata Schneider Glantz Director General Gabriela Peñuelas Guerrero Aída Castilleja González Secretaria Técnica Consejo Asesor-científico Elsa Arroyo Lemus COORDINACIÓN NACIONAL María del Carmen Castro Barrera DE CONSERVACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO CULTURAL Ilse Cimadevilla Cervera Adriana Cruz-Lara Silva Liliana Giorguli Chávez José de Nordenflicht Coordinadora Nacional Ascensión Hernández Martínez Thalía Velasco Castelán Monica Martelli Castaldi Directora de Educación Lorete Mattos para la Conservación Magdalena Rojas Vences Thalía Velasco Castelán Irlanda S. Fragoso Calderas Directora de Conservación e Investigación Diseño Editorial Marcela Mendoza Sánchez Emmanuel Lara Barrera Responsable del Área de Investigación Aplicada Corrección de estilo Paola Ponce Gutiérrez María Eugenia Rivera Pérez Diane Hermanson Responsable del Área de Enlace y Comunicación Revisión de textos en alemán Jürgen Friedrichsen Imagen de portada: ALOIS RIEGL, MAX DVOŘÁK Y GEORG GOTTFRIED DEHIO Imagenes modificadas de dominio público Conversaciones... Año 4, Núm. 5, Julio 2018 es una publicación bianual editada por el Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Secretaría de Cultura. Córboda 45, Colonia Roma, C.P. 06700, Delegación Cuauhtémoc, Ciudad de México, México. Editor responsable: Valerie Magar Meurs. Reservas de Derechos al Uso Exclusivo Nº 04-2015-062409382700-203. ISSN: 2395-9479. Ambos otorgados por el Instituto Nacional del Derecho de Autor. Responsable de la versión electrónica: Coordinación Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural con domicilio en Ex convento de Churubusco, Xicoténcatl y General Anaya s/n, San Diego Churubusco, Del.