Karamojong Cluster Harmonisation Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Violent Conflict Implications of Mega Projects in Nyangatom Woreda, Ethiopia by Fana Gebresenbet, Mercy Fekadu Mulugeta and Yonas Tariku

Briefing Note #5 - May 2019 Violent Conflict Implications of Mega Projects in Nyangatom Woreda, Ethiopia By Fana Gebresenbet, Mercy Fekadu Mulugeta and Yonas Tariku Introduction This briefing note explores conflict in the past 10 years Key Findings in the Nyangatom Woreda of South Omo Zone, South- • Recorded, violent incidents have shown a ern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ region, Ethiopia. decline in 2017/18; The Nyangatom are one of the 16 ethnic groups indig- enous to the Zone. They are found at the southwest- • Cattle raiding remains the most frequent violent ern corner of the Zone adjacent to two international act; boundaries with South Sudan and Kenya. • The decline of violent incidents is not indicative of positive peacebuilding efforts; The study is situated in a physical and political envi- ronment that has shown rapid change due to dam • Changing resource access is a reason for the and large-scale agricultural projects. The Lower Omo decline of violence with some groups and the witnessed rapid transformation over the past decade, increase of violence with others, discouraging following the construction of the Gilgel Gibe III dam, interaction with some and encouraging it with large sugar cane plantations, factories and other others; investments, along with some infrastructural and • According to zone and woreda officials the demographic change. safety net (particularly distribution of food) This briefing is part of a research project “Shifting In/ program is also instrumental in the decline of equality Dynamics in Ethiopia: from Research to Appli- violence; cation (SIDERA).” The project explores environmen- • The decline of violence has to be comple- tal, income and conflict dynamics after the state-led mented with acts of genuine efforts to build development interventions. -

Wahu Kaara of Kenya

THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS: The Life and Work of Wahu Kaara of Kenya By Alison Morse, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS WAHU – KENYA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader ……………………………………………………….. 3 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program ………………………………… 3 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker – Wahu Kaara ….…………………… 4 IV. Conflict History – Kenya …………………………………………………… 5 V. Map – Kenya …………………………………………………………………. 10 VI. Integrated Timeline – Political Developments and Personal History ……….. 11 VII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Wahu Kaara a. The Path………………………………………………………………….. 18 b. Squatters …………………………………………………………………. 20 c. The Dignity of the Family ………………………………………………... 23 d. Namesake ………………………………………………………………… 25 e. Political Awakening……………………………………………..………… 27 f. Exile ……………………………………………………………………… 32 g. The Transfer ……………………………………………………………… 39 h. Freedom Corner ………………………………………………………….. 49 i. Reaffirmation …………………….………………………………………. 56 j. A New Network………………….………………………………………. 61 k. The People, Leading ……………….…………………………………….. 68 VIII. A Conversation with Wahu Kaara ….……………………………………… 74 IX. Best Practices in Peacebuilding …………………………………………... 81 X. Further Reading – Kenya ………………………………………………….. 87 XI. Biography of a Peace Writer -

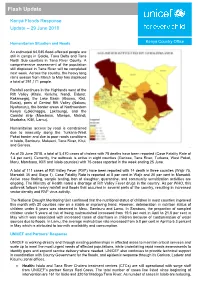

Flash Update

Flash Update Kenya Floods Response Update – 29 June 2018 Humanitarian Situation and Needs Kenya Country Office An estimated 64,045 flood-affected people are still in camps in Galole, Tana Delta and Tana North Sub counties in Tana River County. A comprehensive assessment of the population still displaced in Tana River will be completed next week. Across the country, the heavy long rains season from March to May has displaced a total of 291,171 people. Rainfall continues in the Highlands west of the Rift Valley (Kitale, Kericho, Nandi, Eldoret, Kakamega), the Lake Basin (Kisumu, Kisii, Busia), parts of Central Rift Valley (Nakuru, Nyahururu), the border areas of Northwestern Kenya (Lokichoggio, Lokitaung), and the Coastal strip (Mombasa, Mtwapa, Malindi, Msabaha, Kilifi, Lamu). Humanitarian access by road is constrained due to insecurity along the Turkana-West Pokot border and due to poor roads conditions in Isiolo, Samburu, Makueni, Tana River, Kitui, and Garissa. As of 25 June 2018, a total of 5,470 cases of cholera with 78 deaths have been reported (Case Fatality Rate of 1.4 per cent). Currently, the outbreak is active in eight counties (Garissa, Tana River, Turkana, West Pokot, Meru, Mombasa, Kilifi and Isiolo counties) with 75 cases reported in the week ending 25 June. A total of 111 cases of Rift Valley Fever (RVF) have been reported with 14 death in three counties (Wajir 75, Marsabit 35 and Siaya 1). Case Fatality Rate is reported at 8 per cent in Wajir and 20 per cent in Marsabit. Active case finding, sample testing, ban of slaughter, quarantine, and community sensitization activities are ongoing. -

Kenya, Groundwater Governance Case Study

WaterWater Papers Papers Public Disclosure Authorized June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA GROUNDWATER GOVERNANCE CASE STUDY Public Disclosure Authorized Albert Mumma, Michael Lane, Edward Kairu, Albert Tuinhof, and Rafik Hirji Public Disclosure Authorized Water Papers are published by the Water Unit, Transport, Water and ICT Department, Sustainable Development Vice Presidency. Water Papers are available on-line at www.worldbank.org/water. Comments should be e-mailed to the authors. Kenya, Groundwater Governance case study TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................................. vi ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................................ viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ xi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... xiv 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. GROUNDWATER: A COMMON RESOURCE POOL ....................................................................................................... 1 1.2. CASE STUDY BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

Uganda – Kampala – Sebei Tribe - Tribal Conflict – Kenyan Pokot Tribe – Karamonjong Tribe – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA17790 Country: Uganda Date: 2 February 2006 Keywords: Uganda – Kampala – Sebei tribe - Tribal conflict – Kenyan Pokot tribe – Karamonjong tribe – State protection This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Can you provide information on conflicts between the Sebei tribe and the Kenyan Pokot and the Karamonjong tribe? 2. Is there any evidence of these tribal conflicts been played out in Kampala? 3. Do the Ugandan authorities take action in respect to these tribal conflicts? RESPONSE 1. Can you provide information on conflicts between the Sebei tribe and the Kenyan Pokot and the Karamonjong tribe? The Sebei, Karamojong and Pokot all inhabit the border region in northeast Uganda and northwest Kenya. The Sebei (also known as the Sabei, Sapei, Sabyni and Sabiny) are a very small ethnic group and live in and around Kapchorwa district in northeast Uganda. They live on both sides of the Uganda-Kenya border. The Karamojong (also called Karamonjong and Karimojong) live to the north of the Sebei in the North Eastern part of Uganda and the Pokot (also called the Upe) live to the east and north of the Sebei in Kenya’s West Pokot district as well as northeast Uganda, especially in Nakapiripirit district which neighbours Kapchorwa district. For more information on each of this group, see the Background on Tribes section below. -

Conflicts Between Pastoral Communities in East Africa. Case Study of the Pokot and Turkana

UNIVERSITY OFNAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES Conflicts between Pastoral Communities in East Africa. Case Study of the Pokot and Turkana SIMON MIIRI GITAU R50/69714/2013 SUPERVISOR: DR. OCHIENG KAMUNDAYI A Project submitted in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Master of Arts in International Studies, Institute of diplomacy and International Studies, University of Nairobi i ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been submitted for the award of a Diploma or Degree in any other University Signed…………………………… Date……………………… SIMON MIIRI GITAU This work has been submitted to the Board of Examiners of the University of Nairobi with my approval. Signed……………………………. Date…………………. DR OCHIENG KAMUNDAYI iii DEDICATION To my two sons Brian Gitau and James Ndung’u iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to the following KWS staff assisted in primary data collection: Joseph Kinyanjui, Warden Nasolot National Park West Pokot County and David Kones Warden South Turkana National Reserve Turkana County. Linda Nafula assisted a lot in organizing the data from questionnaire. Fredrick Lala and Lydiah Kisoyani assisted a lot in logistics of administration of the questionnaires I am finally grateful to my family, my wife and my two sons Brian and James for bearing with me during the period I was away from them v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ASTU Anti- Stock Theft Unit CAR Central Africa Republic DPC District Peace Committee DPRC District Peace and Reconciliation Committee IGAD Intergovernmental Authority on Development KPR Kenya -

County Name County Code Location

COUNTY NAME COUNTY CODE LOCATION MOMBASA COUNTY 001 BANDARI COLLEGE KWALE COUNTY 002 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT MATUGA KILIFI COUNTY 003 PWANI UNIVERSITY TANA RIVER COUNTY 004 MAU MAU MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL LAMU COUNTY 005 LAMU FORT HALL TAITA TAVETA 006 TAITA ACADEMY GARISSA COUNTY 007 KENYA NATIONAL LIBRARY WAJIR COUNTY 008 RED CROSS HALL MANDERA COUNTY 009 MANDERA ARIDLANDS MARSABIT COUNTY 010 ST. STEPHENS TRAINING CENTRE ISIOLO COUNTY 011 CATHOLIC MISSION HALL, ISIOLO MERU COUNTY 012 MERU SCHOOL THARAKA-NITHI 013 CHIAKARIGA GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL EMBU COUNTY 014 KANGARU GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL KITUI COUNTY 015 MULTIPURPOSE HALL KITUI MACHAKOS COUNTY 016 MACHAKOS TEACHERS TRAINING COLLEGE MAKUENI COUNTY 017 WOTE TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE NYANDARUA COUNTY 018 ACK CHURCH HALL, OL KALAU TOWN NYERI COUNTY 019 NYERI PRIMARY SCHOOL KIRINYAGA COUNTY 020 ST.MICHAEL GIRLS BOARDING MURANGA COUNTY 021 MURANG'A UNIVERSITY COLLEGE KIAMBU COUNTY 022 KIAMBU INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY TURKANA COUNTY 023 LODWAR YOUTH POLYTECHNIC WEST POKOT COUNTY 024 MTELO HALL KAPENGURIA SAMBURU COUNTY 025 ALLAMANO HALL PASTORAL CENTRE, MARALAL TRANSZOIA COUNTY 026 KITALE MUSEUM UASIN GISHU 027 ELDORET POLYTECHNIC ELGEYO MARAKWET 028 IEBC CONSTITUENCY OFFICE - ITEN NANDI COUNTY 029 KAPSABET BOYS HIGH SCHOOL BARINGO COUNTY 030 KENYA SCHOOL OF GOVERNMENT, KABARNET LAIKIPIA COUNTY 031 NANYUKI HIGH SCHOOL NAKURU COUNTY 032 NAKURU HIGH SCHOOL NAROK COUNTY 033 MAASAI MARA UNIVERSITY KAJIADO COUNTY 034 MASAI TECHNICAL TRAINING INSTITUTE KERICHO COUNTY 035 KERICHO TEA SEC. SCHOOL -

Oyiengo, Nathan Amunga (1941–2015)

Image not found or type unknown Oyiengo, Nathan Amunga (1941–2015) SELINA OYIENGO Selina Oyiengo Nathan Amunga Oyiengo was a pastor and administrator in Kenya. Early Life Nathan Amunga Oyiengo was born to Jackton Oyiengo and Rispa Asami on December 23, 1941, in Ebulali Sub- location of Khwisero Location in the then Kakamega District (now Butere-Mumias District) in Western Kenya.1 His father, Jackton, was a prison officer while his mother was a housewife and a small scale businesswoman. His was a big family of one brother and five sisters. His formative years were spent with his parents and siblings in Kakamega, but when he began going to school, he went to live with his father in Nairobi. For little Nathan, life in the city was a new experience, and it was not long before he found himself in trouble.2 During an interview with his children Jack and Selina in August 2015, he narrated how one afternoon while roaming around aimlessly he found himself on the shoulders of a stranger being whisked away to some unknown destination. The man who had grabbed him was so fast that Nathan did not find his voice until a neighbor called out his name asking where he was going with the strange man. Sensing danger, the would-be kidnapper dropped his human cargo and hurriedly explained that he was only playing with the boy. After giving that brief and completely unconvincing explanation of his weird behavior, the man hurriedly walked away and melted into the gathering crowd. Thus, Nathan was saved from a kidnapping that would have completely altered the course of his life.3 After completing his studies at class four level, he proceeded to class five, six, and finally class seven where he sat for another exam and excelled. -

Migrated Archives): Ceylon

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Ceylon Following earlier settlements by the Dutch and Secret and confidential despatches sent to the Secretary of State for the Portuguese, the British colony of Ceylon was Colonies established in 1802 but it was not until the annexation of the Kingdom of Kandy in 1815 FCO 141/2098-2129: the despatches consist of copies of letters and reports from the Governor that the entire island came under British control. and the departments of state in Ceylon circular notices on a variety of subjects such as draft bills and statutes sent for approval, the publication Ceylon became independent in 1948, and a of orders in council, the situation in the Maldives, the Ceylon Defence member of the British Commonwealth. Queen Force, imports and exports, currency regulations, official visits, the Elizabeth remained Head of State until Ceylon political movements of Ceylonese and Indian activists, accounts of became a republic in 1972, under the name of Sri conferences, lists of German and Italian refugees interned in Ceylon and Lanka. accounts of labour unrest. Papers relating to civil servants, including some application forms, lists of officers serving in various branches, conduct reports in cases of maladministration, medical reports, job descriptions, applications for promotion, leave and pensions, requests for transfers, honours and awards and details of retirements. 1931-48 Secret and confidential telegrams received from the Secretary of State for the Colonies FCO 141/2130-2156: secret telegrams from the Colonial Secretary covering subjects such as orders in council, shipping, trade routes, customs, imports and exports, rice quotas, rubber and tea prices, trading with the enemy, air communications, the Ceylon Defence Force, lists of The binder also contains messages from the Prime Minister and enemy aliens, German and Japanese reparations, honours the Secretary of State for the Colonies to Mr Senanyake on 3 and appointments. -

THE POKOT WORLDVIEW AS an IMPEDIMENT to the SPREAD of CHRISTIANITY AMONG the POKOT PEOPLE 1Tom K

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences Vol.5, No.7, pp.59-76, August 2017 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) THE POKOT WORLDVIEW AS AN IMPEDIMENT TO THE SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY AMONG THE POKOT PEOPLE 1Tom K. Ngeiywo*; 2Ezekiel M. Kasiera; 3Rispah N. Wepukhulu Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology P.O. BOX 190-50100 Kakamega, Kenya ABSTRACT: Christian missionaries established the first mission work among the Pokot people of West Pokot County in 1931 when the Anglican Bible Churchman’s Missionary Society (BCMS) set up a mission centre at Kacheliba. They, however, encountered a lot of resistance and non- response from the Pokot people. To date, the bulk of the Pokot people are still conservative to their traditional lifestyle and reluctant to open up to change and new ideas. This paper examines the Pokot worldview as a challenge to the spread of Christianity among the Pokot people. In so doing, the author seeks to establish ways through which evangelization could be done to make the Pokot people embrace change in order to utilize development opportunities that come with it. A descriptive design was employed for the study. Purposive, snowball and random sampling methods were used to select the respondents. The study was guided by the structural functionalism theory by David Merton of 1910. Descriptive analysis was used to analyze the collected data which was obtained through questionnaires and oral interviews. The study established that the Pokot community is much acculturated and the people are strongly bound together by their tribal customs; majority of whom prefer their traditional lifestyle to modernity. -

Role of Early Warning Systems in Conflict Prevention in Africa: Case

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES ROLE OF EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS IN CONFLICT PREVENTION IN AFRICA: CASE STUDY OF THE ILEMI TRIANGLE PETERLINUS OUMA ODOTE REG NO- R80/96588/2014 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL STUDIES. NOVEMBER 2016 DECLARATION This PhD dissertation is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other university. __________________________ __________________________ Peterlinus Ouma Odote DATE (Candidate) This PhD dissertation has been submitted for examination with our approval as the University of Nairobi supervisors: _______________________________ ________________________ Prof. Maria Nzomo DATE (First Supervisor) _______________________________ ________________________ Prof. Peter Kagwanja DATE (Second Supervisor) i DEDICATION To my wife Judith Linus Akedi, my daughter Tiffany Linus Adela and my Mother Monica Samba for the unconditional support during my study. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work has been accomplished with the support, encouragement and contribution of different people to whom I am sincerely grateful. First and foremost I would like to acknowledge the tireless guidance, patience, contribution, ideas and encouragement of my university supervisors, Prof. Maria Nzomo and Prof. Peter Kagwanja through the different phases of this work. Special acknowledgement is made to both of you for your dedication, unconditional support and mentorship throughout the programme. I also wish to thank the Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies (IDIS) staff for their contribution and efforts to ensure the completion of my research and the Ambassador Francis K Muthaura Foundation for awarding me a PhD Scholarship. I recognize the following individuals and organisations for their tremendous contribution to the successful completion of this study: My friends Prof.