'The Barghest O' Whitby': (A Genealogical Study Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

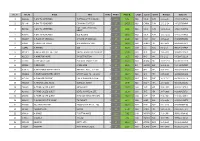

Bertus in Stock 7-4-2014

No. # Art.Id Artist Title Units Media Price €. Origin Label Genre Release Eancode 1 G98139 A DAY TO REMEMBER 7-ATTACK OF THE KILLER.. 1 12in 6,72 NLD VIC.R PUN 21-6-2010 0746105057012 2 P10046 A DAY TO REMEMBER COMMON COURTESY 2 LP 24,23 NLD CAROL PUN 13-2-2014 0602537638949 FOR THOSE WHO HAVE 3 E87059 A DAY TO REMEMBER 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 14-11-2008 0746105033719 HEART 4 K78846 A DAY TO REMEMBER OLD RECORD 1 LP 16,92 NLD VIC.R PUN 31-10-2011 0746105049413 5 M42387 A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS A FLOCK OF SEAGULLS 1 LP 20,23 NLD MOV POP 13-6-2013 8718469532964 6 L49081 A FOREST OF STARS A SHADOWPLAY FOR.. 2 LP 38,68 NLD PROPH HM. 20-7-2012 0884388405011 7 J16442 A FRAMES 333 3 LP 38,73 USA S-S ROC 3-8-2010 9991702074424 8 M41807 A GREAT BIG PILE OF LEAVE YOU'RE ALWAYS ON MY MIND 1 LP 24,06 NLD PHD POP 10-6-2013 0616892111641 9 K81313 A HOPE FOR HOME IN ABSTRACTION 1 LP 18,53 NLD PHD HM. 5-1-2012 0803847111119 10 L77989 A LIFE ONCE LOST ECSTATIC TRANCE -LTD- 1 LP 32,47 NLD SEASO HC. 15-11-2012 0822603124316 11 P33696 A NEW LINE A NEW LINE 2 LP 29,92 EU HOMEA ELE 28-2-2014 5060195515593 12 K09100 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH AND HELL WILL.. -LP+CD- 3 LP 30,43 NLD SPV HM. 16-6-2011 0693723093819 13 M32962 A PALE HORSE NAMED DEATH LAY MY SOUL TO. -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Live to the Metal Music Živi Uz Metal Muziku

LIVE TO THE METAL MUSIC ŽIVI UZ METAL MUZIKU Autori: JOVANA KAZIMIROVIĆ IVA NICULOVIĆ VIII razred, OŠ “Branko Radičević” Negotin Regionalni Centar za talente Bor Mentor: VESNA PRVULOVIĆ prof. Engleskog jezika i književnosti, OŠ “Branko Radičević” Negotin Negotin, aprila 2013. godine 1 Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………3 Summary…………………………………………………………………………………..4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………..5 Metal music………………………………………………………………………………..6 Sub-genres of Heavy Metal……………………………………………………………….10 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………...15 2 Abstract Metal is a movement of music that started essentially with the heavy rock movements. While there was not actual metal during that time, bands were experimenting with heaviness, and it was no surprise that the first metal band (Black Sabbath) was soon to be born. Metal music is a worldwide form of music that has held the attention of younger generations for over 50 years. Metal music has branched off into different sub genres, but one thing is the main motivator for the survival of metal music through all the generations. That is a need for younger generations to rebel against the status quo, to express themselves and their frustration of an outdated way of life. This paper presents the development of metal music from the 1960s to the present day, with special emphasis on some of the metal sub-genre of music. Originally, metal was one genre. But as time passed more genres were born. Today metal is a global movement and has hundreds of sub-genres such as Heavy, Death, Black, Doom, Power, Thrash, Speed, Folk, Industrial, Symphonic, Gothic & Nu-Metal, to name just a few. They range from sheer brutality to smooth and melodic rhythms. -

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES

Dead Master's Beat Label & Distro October 2012 RELEASES: STAHLPLANET – Leviamaag Boxset || CD-R + DVD BOX // 14,90 € DMB001 | Origin: Germany | Time: 71:32 | Release: 2008 Dark and weird One-man-project from Thüringen. Ambient sounds from the world Leviamaag. Black box including: CD-R (74min) in metal-package, DVD incl. two clips, a hand-made booklet on transparent paper, poster, sticker and a button. Limited to 98 units! STURMKIND – W.i.i.L. || CD-R // 9,90 € DMB002 | Origin: Germany | Time: 44:40 | Release: 2009 W.i.i.L. is the shortcut for "Wilkommen im inneren Lichterland". CD-R in fantastic handmade gatefold cover. This version is limited to 98 copies. Re-release of the fifth album appeared in 2003. Originally published in a portfolio in an edition of 42 copies. In contrast to the previous work with BNV this album is calmer and more guitar-heavy. In comparing like with "Die Erinnerung wird lebendig begraben". Almost hypnotic Dark Folk / Neofolk. KNŒD – Mère Ravine Entelecheion || CD // 8,90 € DMB003 | Origin: Germany | Time: 74:00 | Release: 2009 A release of utmost polarity: Sudden extreme changes of sound and volume (and thus, in mood) meet pensive sonic mindscapes. The sounds of strings, reeds and membranes meet the harshness and/or ambience of electronic sounds. Music as harsh as pensive, as narrative as disrupt. If music is a vehicle for creating one's own world, here's a very versatile one! Ambient, Noise, Experimental, Chill Out. CATHAIN – Demo 2003 || CD-R // 3,90 € DMB004 | Origin: Germany | Time: 21:33 | Release: 2008 Since 2001 CATHAIN are visiting medieval markets, live roleplaying events, roleplaying conventions, historic events and private celebrations, spreading their “Enchanting Fantasy-Folk from worlds far away”. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE June 2017

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE June 2017 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you w ill find a full list w ith all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, w e have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 12.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they starte d with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

A Christian Martyr in Christiansand Norway

1 A Christian Martyr in Christiansand Norway. The diary of the Turin Shroud ¨God experiment¨. ¨The life of Sasha Edomita, a Mk-Ultra targeted individual of police gangstalking and deadly electronic harassment population control.¨ Part 1 details the reality of the Lucifer-God Jesus v2 experiment. Part 2 is a compilation of my diary from the years 2015-2018. My diary has not been edited ever, due to trauma. I present to you the most scandalous crime in judicial and religious history: THE TURIN-SHROUD CLONING EXPERIMENT!!! An interdimensional breatharian buddha with amnesia who dreamt his life away frozen in fearful denial. ¨Dreaming away in lucid dreams, I was never from this world, but an actual Heavenly being. I saw my dream-life as of greater value to the Earth, putting myself low, following the Bible, but my mom forcibly woke me every morning, never told me the truth, abused me emotionally and spiritually, as they spirit cooked me and cloned me as food for 20 years until they eventually tore off my wings so I could not dream, and locked me up at a mental asylum to kill me off with no crime records. Without ever telling me why or telling me the truth… Thank you father, mother and nation. Now you know what karma God has in store for you. For I clinged to life, almost dying every night for the 6 last years, all alone, surveyed by all of Hell. And here is their crime record, the precursor to judgement day. Let me tell you my tale and seal their fates. -

Metaldata: Heavy Metal Scholarship in the Music Department and The

Dr. Sonia Archer-Capuzzo Dr. Guy Capuzzo . Growing respect in scholarly and music communities . Interdisciplinary . Music theory . Sociology . Music History . Ethnomusicology . Cultural studies . Religious studies . Psychology . “A term used since the early 1970s to designate a subgenre of hard rock music…. During the 1960s, British hard rock bands and the American guitarist Jimi Hendrix developed a more distorted guitar sound and heavier drums and bass that led to a separation of heavy metal from other blues-based rock. Albums by Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple in 1970 codified the new genre, which was marked by distorted guitar ‘power chords’, heavy riffs, wailing vocals and virtuosic solos by guitarists and drummers. During the 1970s performers such as AC/DC, Judas Priest, Kiss and Alice Cooper toured incessantly with elaborate stage shows, building a fan base for an internationally-successful style.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . “Heavy metal fans became known as ‘headbangers’ on account of the vigorous nodding motions that sometimes mark their appreciation of the music.” (Grove Music Online, “Heavy metal”) . Multiple sub-genres . What’s the difference between speed metal and death metal, and does anyone really care? (The answer is YES!) . Collection development . Are there standard things every library should have?? . Cataloging . The standard difficulties with cataloging popular music . Reference . Do people even know you have this stuff? . And what did this person just ask me? . Library of Congress added first heavy metal recording for preservation March 2016: Master of Puppets . Library of Congress: search for “heavy metal music” April 2017 . 176 print resources - 25 published 1980s, 25 published 1990s, 125+ published 2000s . -

Nr Kat Artysta Tytuł Title Supplement Nośnik Liczba Nośników Data

nr kat artysta tytuł title nośnik liczba data supplement nośników premiery 9985841 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us black LP+CD LP / Longplay 2 2015-10-30 9985848 '77 Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2015-10-30 88697636262 *NSYNC The Collection CD / Longplay 1 2010-02-01 88875025882 *NSYNC The Essential *NSYNC Essential Rebrand CD / Longplay 2 2014-11-11 88875143462 12 Cellisten der Hora Cero CD / Longplay 1 2016-06-10 88697919802 2CELLOSBerliner Phil 2CELLOS Three Language CD / Longplay 1 2011-07-04 88843087812 2CELLOS Celloverse Booklet Version CD / Longplay 1 2015-01-27 88875052342 2CELLOS Celloverse Deluxe Version CD / Longplay 2 2015-01-27 88725409442 2CELLOS In2ition CD / Longplay 1 2013-01-08 88883745419 2CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb DVD-V / Video 1 2013-11-05 88985349122 2CELLOS Score CD / Longplay 1 2017-03-17 0506582 65daysofstatic Wild Light CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 0506588 65daysofstatic Wild Light Ltd. Edition CD / Longplay 1 2013-09-13 88985330932 9ELECTRIC The Damaged Ones CD Digipak CD / Longplay 1 2016-07-15 82876535732 A Flock Of Seagulls The Best Of CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88883770552 A Great Big World Is There Anybody Out There? CD / Longplay 1 2014-01-28 88875138782 A Great Big World When the Morning Comes CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-13 82876535502 A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 82876535512 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88875157852 A Tribe Called Quest People'sThe Paths Instinctive Of Rhythm Travels and the CD / Longplay 1 2015-11-20 82876535492 A Tribe Called Quest ThePaths Low of RhythmEnd Theory (25th Anniversary CD / Longplay 1 2003-08-18 88985377872 A Tribe Called Quest We got it from Here.. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you will find a full list with all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, we have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 11.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they started with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

Anathema Universal Mp3, Flac, Wma

Anathema Universal mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Universal Country: UK & Europe Released: 2013 Style: Alternative Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1602 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1433 mb WMA version RAR size: 1832 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 731 Other Formats: VOX MOD ADX APE AU FLAC DTS Tracklist Hide Credits Untouchable Part 1 CD-1 6:56 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Untouchable Part 2 CD-2 5:43 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Thin Air CD-3 5:51 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh*, John Douglas , Vincent Cavanagh Dreaming Light CD-4 5:39 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* The Storm Before The Calm CD-5 9:13 Written-By – John Douglas , Vincent Cavanagh Everything CD-6 5:36 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* A Simple Mistake CD-7 8:11 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* The Beginning And The End CD-8 4:41 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Universal CD-9 7:26 Written-By – John Douglas , Vincent Cavanagh Closer CD-10 5:43 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* A Natural Disaster CD-11 6:18 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Flying CD-12 8:10 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Untouchable Part 1 DVD-1 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Untouchable Part 2 DVD-2 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Thin Air DVD-3 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh*, John Douglas , Vincent Cavanagh Dreaming Light DVD-4 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* Lightning Song DVD-5 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* The Storm Before The Calm DVD-6 Written-By – John Douglas , Vincent Cavanagh Everything DVD-7 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* A Simple Mistake DVD-8 Written-By – Daniel Cavanagh* The Beginning And The -

Paradise Lost – Live at Rockpalast 1995

Paradise Lost – Live at Rockpalast 1995 (62:27, CD+DVD, MiG-Music, 2019) Beim Rockpalast handelt es sich um eine Fernsehsendung des Westdeutschen Rundfunks, welche mit Unterbrechungen seit 1974 existiert. Im Rahmen des Formates wurden in der Vergangenheit auch immer wieder Festivals produziert, um später die Auftritte der verschiedenen Bands im Fernsehen zu übertragen. Der Titel „Live at Rockpalast 1995“ für dieses Album ist daher erst einmal ein wenig irreführend, da es sich bei vorliegendem Ton- und Bilddokument um den Auftritt von Paradise Lost beim Bizarre Festival 1995 handelt. Das Bizarre existierte zu diesem Zeitpunkt schon seit acht Jahren und war gerade auf dem Weg, sich zu Deutschlands Festival Nummer Eins für alternative Musik jeglicher Couleur zu mausern. Bis zu diesem Zeitpunkt waren u.a. so namhafte Bands wie Siouxsie and the Banshees, New Model Army, Iggy Pop, Einstürzende Neubauten, Ramones, The Pogues, Pixies, Sonic Youth, Bad Religion, Die Ärzte und Biohazard beim Bizarre Festival aufgetreten. Dabei hatte das Festival über die Jahre hinweg immer wieder seinen Veranstaltungsort gewechselt. Nach mehreren Gastspielen in Berlin und auf dem Loreleyfelsen in Sankt Goarshausen sowie Gastspielen in Gießen und Alsfeld, fand das Bizarre 1994 zum ersten Mal in Köln statt. 1995 kehrten die Veranstalter in die Domstadt zurück. Allerdings wählten sie dieses Mal nicht den Kölner Jugendpark als Location, sondern stattdessen einen staubigen und herzlosen Deutzer Parkplatz namens P23 – jenen Ort, an dem schon im Folgejahr mit dem Beginn der Kölnarena (heute Lanxess Arena) begonnen werden sollte. Paradise Lost waren 1995 im Zenit ihres Erfolges angekommen. Die Band aus dem englischen Halifax war Anfang der 90er neben Anathema und My Dying Bride zu den „Big Three“ des Gothic Metal gerechnet worden. -

A User's Guide to the Apocalypse

A User's Guide to the Apocalypse [a tale of survival, identity, and personal growth] [powered by Chuubo's Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine] [Elaine “OJ” Wang] This is a preview version dating from March 28, 2017. The newest version of this document is always available from http://orngjce223.net/chuubo/A%20User%27s%20Guide %20to%20the%20Apocalypse%20unfinished.pdf. Follow https://eternity-braid.tumblr.com/ for update notices and related content. Credits/Copyright: Written by: Elaine “OJ” Wang, with some additions and excerpts from: • Ops: the original version of Chat Conventions (page ???). • mellonbread: Welcome to the Future (page ???), The Life of the Mind (page ???), and Corpseparty (page ???), as well as quotes from wagglanGimmicks, publicFunctionary, corbinaOpaleye, and orangutanFingernails. • godsgifttogrinds: The Game Must Go On (page ???). • eternalfarnham: The Azurites (page ???). Editing and layout: I dream of making someone else do it. Based on Replay Value AU of Homestuck, which was contributed to by many people, the ones whom I remember best being Alana, Bobbin, Cobb, Dove, Impern, Ishtadaal, Keleviel, Mnem, Muss, Ops, Oven, Rave, The Black Watch, Viridian, Whilim, and Zuki. Any omissions here are my own damn fault. In turn, Replay Value AU itself was based upon Sburb Glitch FAQ written by godsgifttogrinds, which in turn was based upon Homestuck by Andrew Hussie. This is a supplement for the Chuubo's Marvelous Wish-Granting Engine system, which was written by Jenna Katerin Moran. The game mechanics belong to her and are used with permission. Previous versions of this content have appeared on eternity-braid.tumblr.com, rvdrabbles.tumblr.com, and archiveofourown.org.