Twentieth Century Organ Works As Pedagogical Devices: Using Select

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

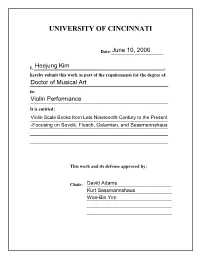

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ ViolinScaleBooks fromLateNineteenth-Centurytothe Present -FocusingonSevcik,Flesch,Galamian,andSassmannshaus Adocumentsubmittedtothe DivisionofGraduateStudiesandResearchofthe UniversityofCincinnati Inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DOCTORAL OFMUSICALARTS inViolinPerformance 2006 by HeejungKim B.M.,Seoul NationalUniversity,1995 M.M.,TheUniversityof Cincinnati,1999 Advisor:DavidAdams Readers:KurtSassmannshaus Won-BinYim ABSTRACT Violinists usuallystart practicesessionswithscale books,andtheyknowthe importanceofthem asatechnical grounding.However,performersandstudents generallyhavelittleinformation onhowscale bookshave beendevelopedandwhat detailsaredifferentamongmanyscale books.Anunderstanding ofsuchdifferences, gainedthroughtheidentificationandcomparisonofscale books,canhelp eachviolinist andteacherapproacheachscale bookmoreintelligently.Thisdocumentoffershistorical andpracticalinformationforsome ofthemorewidelyused basicscalestudiesinviolin playing. Pedagogicalmaterialsforviolin,respondingtothetechnicaldemands andmusical trendsoftheinstrument , haveincreasedinnumber.Amongthem,Iwillexamineand comparethe contributionstothescale -

News 2009 Boosey & Hawkes · Schott Music Spring · Summer Peter-Lukas Graf Turns 80!

News 2009 Boosey & Hawkes · Schott Music Spring · Summer Peter-Lukas Graf turns 80! Born in Zurich (Switzerland) in 1929, Peter-Lukas Graf studied the flute with André Jaunet (Zurich), Marcel Moyse and Roger Cortet (Paris). He was awarded the First Prize as flautist and the conductor’s diploma (Eugène Bigot). The period as a principal flutist in Winterthur and in the Swiss Festival Orchestra Lucerne was succeded by many years of full time opera and symphonic conduct- ing. At present, Peter-Lukas Graf plays, conducts and teaches internationally. He has made numerous CD recordings, radio and television productions. He now lives in Basle (Switzerland) where he is professor at the Music Academy. Check-up 20 Basic Studies for Flautists (Eng./Ger.) ISMN 979-0-001-08152-8 ED 7864 · £ 12.50 / € 18,95 (Ital./Fr.) Da capo! Encore! ISMN 979-0-001-08256-3 ED 8010 · £ 11.99 / € 17,95 Zugabe! The Finest Encore Pieces from Bach to Joplin Interpretation for flute and guitar How to shape a melodic line ISMN 979-0-001-08184-9 (Eng.) ED 7908 · £ 12.50 / € 18,95 ISMN 979-0-001-08465-9 ED 9235 · £ 19.50 / € 29,95 for flute and piano ISMN 979-0-001-08185-6 ED 7909 · £ 12.50 / € 18,95 The Singing Flute How to develop an expres- sive tone. A melody book for flautists (Eng./Ger./Fr.) ISBN 978-3-7957-5751-9 ED 9627 · £ 9.50 / € 14,95 MA 4024-01 · 01/09 Dr. Peter Hanser-Strecker Publisher Welcome to Schott’s world of music! I am pleased to present you with just a few of the latest items from the different areas of our extensive publishing programme. -

My Lecture-Recital, Deli

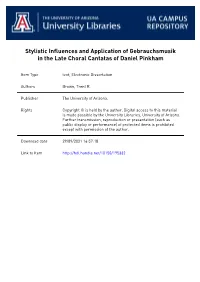

Stylistic Influences and Application of Gebrauchsmusik in the Late Choral Cantatas of Daniel Pinkham Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Brown, Trent R. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 16:57:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/195332 STYLISTIC INFLUENCES AND APPLICATION OF GEBRAUCHSMUSIK IN THE LATE CHORAL CANTATAS OF DANIEL PINKHAM by Trent R. Brown _________________________ Copyright © Trent R. Brown 2009 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Trent R. Brown entitled Stylistic Influences and Application of Gebrauchsmusik in the Late Choral Cantatas of Daniel Pinkham and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. _______________________________________________Date: 11/10/09 Bruce Chamberlain _______________________________________________Date: 11/10/09 Elizabeth Schauer _______________________________________________Date: 11/10/09 Robert Bayless Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Bengt Hambraeus' Livre D'orgue

ORGAN REGISTRATIONS IN BENGT HAMBRAEUS’ LIVRE D’ORGUE CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS AND REVISIONS Mark Christopher McDonald Organ and Church Music Area Department of Performance Schulich School of Music McGill University, Montreal, Quebec May 2017 A paper submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of D.Mus. Performance Studies. © 2017 Mark McDonald CONTENTS Index of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... vi Résumé ..................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. viii I. Introduction – Opening a Time Capsule .................................................................................. 1 Bengt Hambraeus and the Notion of the “Time Capsule” .................................................... 2 Registration Indications in : Interpretive Challenges......................................... 3 Livre d’orgue Project Overview ................................................................................................................ 4 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... -

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected]

ORGAN ESSENTIALS Manual Technique Sheri Peterson [email protected] Piano vs. Organ Tone “…..the vibrating string of the piano is loudest immediately after the attack. The tone quickly decays, or softens, until the key is released or until the vibrations are so small that no tone is audible.” For the organ, “the volume of the tone is constant as long as the key is held down; just prior to the release it is no softer than at the beginning.” Thus, the result is that “due to the continuous strength of the organ tone, the timing of the release is just as important as the attack.” (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 9 Suppl.) Basic Manual Technique • Hand Posture - Curve the fingers. Keep the hand and wrist relaxed. There is no need to apply excessive pressure to the keys. • Attack and Release - Precise rhythmic attack and release are crucial. The release is just as important as the attack. • Legato – Essential to effective hymn playing. • Independence – Finger and line. Important Listening Skills • Perfect Legato – One finger should keep a key depressed until the moment a new tone begins. Listen for a perfectly smooth connection. • Precise Releases – Listen for the timing of the release. Practice on a “silent” (no stops pulled) manual, listening for the clicks of the attacks and releases. • Independence of Line – When playing lines (voices) together, listen for a single line to sound the same as it does when played alone. (Don Cook: Organ Tutor, 2008, Intro 10 Suppl.) Fingering Technique The goal of fingering is to provide for the most efficient motion as possible. -

PIERRE COCHEREAU: a LEGACY of IMPROVISATION at NOTRE DAME DE PARIS By

PIERRE COCHEREAU: A LEGACY OF IMPROVISATION AT NOTRE DAME DE PARIS By ©2019 Matt Gender Submitted to the graduate degree program in School of Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ______________________________ Chairperson: Michael Bauer ______________________________ James Higdon ______________________________ Colin Roust ______________________________ David Alan Street ______________________________ Martin Bergee Date Defended: 05/15/19 The Dissertation Committee for Matt Gender certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: PIERRE COCHEREAU: A LEGACY OF IMPROVISATION AT NOTRE DAME DE PARIS _____________________________ Chairperson: Michael Bauer Date Approved: 05/15/19 ii ABSTRACT Pierre Cochereau (1924–84) was the organist of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and an improviser of organ music in both concert and liturgical settings. He transformed the already established practices of improvising in the church into a modern artform. He was influenced by the teachers with whom he studied, including Marcel Dupré, Maurice Duruflé, and André Fleury. The legacy of modern organ improvisation that he established at Notre Dame in Paris, his synthesis of influences from significant figures in the French organ world, and his development of a personal and highly distinctive style make Cochereau’s recorded improvisations musically significant and worthy of transcription. The transcription of Cochereau’s recorded improvisations is a task that is seldom undertaken by organists or scholars. Thus, the published improvisations that have been transcribed are musically significant in their own way because of their relative scarcity in print and in concert performances. This project seeks to add to this published collection, giving organists another glimpse into the vast career of this colorful organist and composer. -

The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study*

Performance Practice Review Volume 5 Article 2 Number 2 Fall The mplicI ations of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study Desmond Hunter Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Hunter, Desmond (1992) "The mpI lications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 5: No. 2, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199205.02.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol5/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Renaissance Keyboard Fingering The Implications of Fingering Indications in Virginalist Sources: Some Thoughts for Further Study* Desmond Hunter The fingering of virginalist music has been discussed at length by various scholars.1 The topic has not been exhausted however; indeed, the views expressed and the conclusions drawn have all too frequently been based on limited evidence. I would like to offer some observations based on both a knowledge of the sources and the experience gained from applying the source fingerings in performances of the music. I propose to focus on two related aspects: the fingering of linear figuration and the fingering of graced notes. Our knowledge of English keyboard fingering is drawn from the information contained in virginalist sources. Fingerings scattered Revised version of a paper presented at the 25th Annual Conference of the Royal Musical Association in Cambridge University, April 1990. -

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art

The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art By Copyright 2016 Song Yi Park Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer ________________________________ Dr. James Higdon ________________________________ Dr. Colin Roust ________________________________ Dr. Bradley Osborn ________________________________ Professor Jerel Hildig Date Defended: November 1, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Song Yi Park certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Baroque Offertoire : Apotheosis of the French Organ Art ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Michael Bauer Date approved: November 1, 2016 ii Abstract During the French Baroque period, the function of the organ was primarily to serve the liturgy. It was an integral part of both Mass and the office of Vespers. Throughout these liturgies the organ functioned in alteration with vocal music, including Gregorian chant, choral repertoire, and fauxbourdon. The longest, most glorious organ music occurred at the time of the offertory of the Mass. The Offertoire was the place where French composers could develop musical ideas over a longer stretch of time and use the full resources of the French Classic Grand jeu , the most colorful registration on the French Baroque organ. This document will survey Offertoire movements by French Baroque composers. I will begin with an introductory discussion of the role of the offertory in the Mass and the alternatim plan in use during the French Baroque era. Following this I will look at the tonal resources of the French organ as they are incorporated into French Offertoire movements. -

Tuesday, February 12

The Organizer — — February — 2008 A G O Monthly Newsletter The Atlanta Chapter L O G O AMERICAN GUILD of ORGANISTS The Organizer FEBRUARY 2008 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Ann Labounsky has earned TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 12 an enviable international reputation as Ann Labounsky, organist Atlanta a virtuoso performer and improvisor at the organ, and particularly, as a leading “Life and Music of Jean Langlais” Chapter Officers American disciple of Jean Langlais. Dean From 1962 to 1964 Ann Labounsky PEACHTREE CHRISTIAN CHURCH Michael Morgan lived and studied in Paris as a recipient 150 Peachtree Street NE at Spring of a Fulbright Grant. As an organ Atlanta, Georgia Sub-Dean 404.876.5535 James Mellichamp student of André Marchal and Jean Langlais, she immersed herself in the Host: Herb Buffington Secretary French organ tradition; she studied Betty Williford 6:00 pm Punch Bowl most of Langlais’s compositions with Treasurer the composer, and played them for him 6:30 pm Dinner & Meeting Charlene Ponder on the organ at Sainte-Clotilde. In 1964, 8:00 pm Recital while she was Langlais’s student at the Registrar Schola Cantorum, she earned the Dinner Reservations ($12) Michael Morris due by 2/7/08 Diplôme de Virtuosité with mention Newsletter Editor maximum in both performance and improvisation. Additional study was Charles Redmon Ann Labounsky’s early training was under the with Suzanne Chaisemartin and Marcel direction of Paul J. Sifler and John LaMontaine Chaplain Dupré. She was awarded the diploma in New York City. She was awarded a Bachelor Rev. Dr. John Beyers with the highest honors at the organ of Music degree from the Eastman School of Auditor competition at the Soissons Cathedral. -

The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music After the Revolution

Technological University Dublin ARROW@TU Dublin Doctoral Applied Arts 2013-8 The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly Technological University Dublin Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Connolly, D. (2013) The Influence of Plainchant on rF ench Organ Music after the Revolution. Doctoral Thesis. Dublin, Technological University Dublin. doi:10.21427/D76S34 This Theses, Ph.D is brought to you for free and open access by the Applied Arts at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License The Influence of Plainchant on French Organ Music after the Revolution David Connolly, BA, MA, HDip.Ed Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music Dublin Institute of Technology Conservatory of Music and Drama Supervisor: Dr David Mooney Conservatory of Music and Drama August 2013 i I certify that this thesis which I now submit for examination for the award of Doctor of Philosophy in Music, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. This thesis was prepared according to the regulations for postgraduate study by research of the Dublin Institute of Technology and has not been submitted in whole or in part for another award in any other third level institution. -

Interaktiv June 2006 Page 1 Interaktiv Noch Zusätzlich Einen 90-Minütigen Vortrag Über Das Deutsche Gesundheits- Wesen an Einem Der Anderen Konferenztage, Bei Dem U.A

Liebe GLD-Mitglieder! von Frieda Ruppaner-Lind, GLD Administrator ie Sie bereits durch mehrere Ankündigungen unserer Verbandsleitung Werfahren haben, wird mit Beginn des Jahres 2006 keine zusätzliche Gebühr für die Mitgliedschaft in den ATA-Divisions mehr erhoben. Jedes ATA-Mitglied kann außerdem einer beliebigen Anzahl von Divisions beitreten. Dies führt zu einer Vereinfachung für die Division Administrators, die sich jetzt nicht mehr mit separaten Budgets abgeben müssen und automa- tisch für jede ATA-Konferenz zwei Sprecher direkt einladen können. Dies hängt auch nicht mehr von der Größe der einzelnen Divisions ab und gibt somit den kleineren Divisions die Möglichkeit, ein besseres Programm zu bieten. Ein anderer positiver Effekt ist die Erhöhung der Mitgliederzahlen in allen Divisions. Im Vergleich zum Vorjahr verfügt die GLD jetzt über ca. 950 Mitglieder, was einer Steigerung von 350 Mitgliedern entspricht. Für die Mitgliedschaft in der GLD-Liste in Yahoo Groups ist nach wie vor die Mitgliedschaft in der Division Voraussetzung. Auch hier ist ein Anstieg der Mitgliederzahl auf 231 Mitglieder zu verzeichnen, was gegenüber dem Vorjahr allerdings geringfügig ist. Trotzdem ist die Liste wie immer sehr aktiv und ich freue mich über die vielen interessanten Beiträge. Bevor der Sommer mit den hierzulande recht heißen Temperaturen heran- naht, waren die GLD-Administratoren wie im letzten Jahr wieder an der Gestaltung des deutschen Programmteils der ATA-Konferenz in New Orleans beteiligt. Wir haben uns auch die Vorschläge notiert, die während der GLD- Jahresversammlung in Seattle von Mitgliedern gemacht wurden; einer der Vorschläge lautete, etwas zum Thema Medizin zu präsentieren. Diesen Wunsch werden wir erfüllen können: Im Rahmen eines dreistündigen interaktiv Seminars am Mittwoch wird Prof. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music.