Georgia Cobb Marietta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois at Shiloh

* o « o ^ •^^ .^^ .-1°^ .HO, »!v: ' '^ * 9.^ ^^^. - ^ •^ o .0^ A 9. <^^ . o > \{ 'i °o . Chicago, Illinois, January, 1905. To the Governor of Illinois: Sir:—The undersigned members of the Illinois Battlefield Commission, appointed by Governor John R. Tanner, under an act passed by the General Assembly of Illinois, approved by the Governor June 9, 1897, and followed by supple- mentary acts, to locate positions and erect monu- ments on the battlefield of Shiloh in honor of the Illinois Troops engaged in the battle, have the honor of submitting a report of what has been accomplished in pursuance of their duties under said acts. Respectfully submitted; Gustav A. Bussey, George Mason, Israel P. Rumsey, Timothy Slattery, Thomas A. Weisner, J. B. Nulton, Isaac Yantis, A. F. McEwen, Benson Wood, Sheldon C. Ayres. Commissioners ILLINOIS AT S H I LO H REPORT OF THE X U \ n 'i Shiloh Battlefield Commission AND CEREMONIES AT THE DEDICATION OF THE MONUMENTS ERECTED TO MARK THE POSITIONS OF THE ILLINOIS COMMANDS ENGAGED IN THE BATTLE The Story of the Battle, by Stanley Waterloo t Compiled by Major George Mason, Secretary of the Commission Illinois at Shiloh THE BATTLE OF SHILOH The Battle of Shiloh, fought April 6 and 7, 1862, was one of the great battles of history, one the importance and quality of which will be more and more recognized as time passes. It was a battle in which were included half a dozen bloody smaller battles, it was a battle where con- ditions were such that there was almost the closeness of conflicts in medieval times, and where regiments and brigades of raw recruits showed in desperate struggle with each other what American courage is. -

Cobb County, Georgia and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 4 Cobb County COBB COUNTY, GEORGIA AND INCORPORATED AREAS COMMUNITY NAME COMMUNITY NUMBER ACWORTH, CITY OF 130053 AUSTELL, CITY OF 130054 COBB COUNTY 130052 (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) KENNESAW, CITY OF 130055 MARIETTA, CITY OF 130226 POWDER SPRINGS, CITY OF 130056 SMYRNA, CITY OF 130057 REVISED: MARCH 4, 2013 FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 13067CV001D NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study (FIS) report may not contain all data available within the Community Map Repository. Please contact the Community Map Repository for any additional data. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may revise and republish part or all of this FIS report at any time. In addition, FEMA may revise part of this FIS report by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the FIS report. Therefore, users should consult with community officials and check the Community Map Repository to obtain the most current FIS report components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: August 18, 1992 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: December 16, 2008 Revised Countywide FIS Effective Date: March 4, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Purpose of Study 1 1.2 Authority and Acknowledgments 1 1.3 Coordination 3 2.0 AREA STUDIED 5 2.1 Scope of Study 5 2.2 Community Description 10 2.3 Principal Flood Problems -

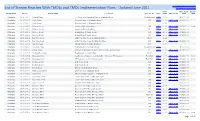

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

State of the Park Report, Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park, Georgia

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior State of the Park Report Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park Georgia November 2013 National Park Service. 2013. State of the Park Report for Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. State of the Park Series No. 8. National Park Service, Washington, D.C. On the cover: Civil War cannon and field of flags at Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. Disclaimer. This State of the Park report summarizes the current condition of park resources, visitor experience, and park infrastructure as assessed by a combination of available factual information and the expert opinion and professional judgment of park staff and subject matter experts. The internet version of this report provides the associated workshop summary report and additional details and sources of information about the findings summarized in the report, including references, accounts on the origin and quality of the data, and the methods and analytic approaches used in data collection and assessments of condition. This report provides evaluations of status and trends based on interpretation by NPS scientists and managers of both quantitative and non- quantitative assessments and observations. Future condition ratings may differ from findings in this report as new data and knowledge become available. The park superintendent approved the publication of this report. Executive Summary The mission of the National Park Service is to preserve unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of national parks for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations. NPS Management Policies (2006) state that “The Service will also strive to ensure that park resources and values are passed on to future generations in a condition that is as good as, or better than, the conditions that exist today.” As part of the stewardship of national parks for the American people, the NPS has begun to develop State of the Park reports to assess the overall status and trends of each park’s resources. -

Lucinda Hardage – from the Files at Kennesaw Mountain NBP

Lucinda Hardage – from the files at Kennesaw Mountain NBP Edited by Kimberlye M. Cole, 2013 Miss Lucinda Hardage, symbol of America, she saw it all – How war came to the land she knew for ninety-two years, saw boys in gray entrench upon her father’s farm in face of an advancing wave of blue. She lived to see those entrenchments become a part of a national park dedicated to perpetuate for America the memory of those stirring days of 1864, when soldiers and civilians, north and south, demonstrated that courageous hold characteristically American. To historians and other park officials, Miss Lucinda Hardage gave a wealth of first-hand information about the battle of Kennesaw Mountain, details and anecdotes available from no other source. She was a symbol of an era, the last direct link with a historic past. When she died July 14, 1940, seventy six years after the battle of Kennesaw, that personal link was broken. Miss Lucinda was born January 14, 1848, the daughter of George Washington and Mary Ann Cook Hardage. Her birthplace was a log cabin of one room, south of the Burnt Hickory Road, close to the base of Little Kennesaw Mountain. From Hall County, Georgia, her father had moved to Cobb County and built a cabin in Indian country. Miss Lucinda recalled that he cleared the land by day and improved the house after dark, with her mother’s assistance. Miss Lucinda was one of fourteen children. Two of her sisters who died in infancy are buried at the foot of the large cedar tree (now gone) near the trailside exhibit at Little Kennesaw. -

Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Rule 391-3-6-.03. Water Use Classifications and Water Quality Standards ( 1) Purpose. The establishment of water quality standards. (2) W ate r Quality Enhancement: (a) The purposes and intent of the State in establishing Water Quality Standards are to provide enhancement of water quality and prevention of pollution; to protect the public health or welfare in accordance with the public interest for drinking water supplies, conservation of fish, wildlife and other beneficial aquatic life, and agricultural, industrial, recreational, and other reasonable and necessary uses and to maintain and improve the biological integrity of the waters of the State. ( b) The following paragraphs describe the three tiers of the State's waters. (i) Tier 1 - Existing instream water uses and the level of water quality necessary to protect the existing uses shall be maintained and protected. (ii) Tier 2 - Where the quality of the waters exceed levels necessary to support propagation of fish, shellfish, and wildlife and recreation in and on the water, that quality shall be maintained and protected unless the division finds, after full satisfaction of the intergovernmental coordination and public participation provisions of the division's continuing planning process, that allowing lower water quality is necessary to accommodate important economic or social development in the area in which the waters are located. -

Tour Stops Section #11 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain

1 The Bandy Heritage Center for Northwest Georgia Atlanta Campaign Driving Tour Kennesaw Mountain Tour Stops Section #11 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain Heavy rain plagued both armies as they withdrew from their Dallas-New Hope-Pickett’s Mill lines during the first weeks of June 1864. Forced to return to the Western and Atlantic Railroad to supply his men, Sherman concentrated his forces in the Acworth-Big Shanty region. The lack of roads and the impassable conditions of the ones that existed prevented Sherman from continuing his strategy of moving around Johnston’s flanks in order to pry him from his strong defensive positions. A more direct approach to Atlanta would be needed. Johnston, having no choice but to shadow Sherman’s movements, established a new line south of Acworth. Taking advantage of several prominent heights in the area, Johnston’s line ran north from Lost Mountain to Gilgal Church, turned east at Pine Mountain, and extended past Brush Mountain to the Western and Atlantic Railroad. This line enabled Johnston to protect both his communications and supply lines as well as the approaches to Marietta. Taking advantage of the wild and broken terrain occupied by his army, Johnston turned the ridges and hills into an extended fortress of earthworks, rifle pits, and artillery firing positions that dominated all avenues of approach across his front. Reinforced by the arrival of Major General Francis Blair’s XVII Corps of McPherson’s Army of the Tennessee, Sherman began his advance to Marietta on June 10, 1864. McPherson, on the left, moved along the railroad toward Marietta. -

Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign'

H-CivWar Bledsoe on Hess, 'Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign' Review published on Wednesday, May 21, 2014 Earl J. Hess. Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign. Civil War America Series. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. xvi + 322 pp. $35.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-1-4696-0211-0. Reviewed by Drew S. Bledsoe (Lee University) Published on H-CivWar (May, 2014) Commissioned by Hugh F. Dubrulle Sherman’s Failed Experiment The Atlanta campaign of 1864 was pivotal to the Union’s efforts to secure the Confederate heartland. It also contributed immensely to Abraham Lincoln’s reelection bid in November of 1864. The capture of Atlanta helped ensure that the United States would not abandon its efforts to prosecute the American Civil War to a victorious conclusion. Despite the campaign’s importance, however, it has not enjoyed the same level of historical attention as other Civil War campaigns, particularly those in the Virginia theater of operations. Nevertheless, several important studies of the Atlanta campaign dominate the historiography of the Civil War in the West, particularly William R. Scaife’s outstanding (and out-of-print) The Campaign for Atlanta (1993) and Albert E. Castel’s Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864 (1992). Still, detailed battle studies of individual engagements within the Atlanta campaign are strikingly scarce. Thankfully, this trend has changed in recent years, and Earl J. Hess’s Kennesaw Mountain: Sherman, Johnston, and the Atlanta Campaign is not only an outstanding study of one of the most important battles of the Atlanta campaign, but also among the best battle studies in recent memory. -

Fecal Coliform TMDL Report

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Nineteen Stream Segments in the Tennessee River Basin for Fecal Coliform Submitted to: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia Submitted by: The Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Atlanta, Georgia January 2004 Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation January 2004 Tennessee River Basin (Fecal coliform) Table of Contents Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Watershed Description......................................................................................................1 1.3 Water Quality Standard.....................................................................................................5 2.0 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................ 8 3.0 SOURCE ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................................... 9 3.1 Point Source Assessment ................................................................................................. 9 3.2 Nonpoint Source Assessment........................................................................................ -

Effects of Internal Loading on Algal Biomass in Lake Allatoona, a Southeastern Piedmont Impoundment

EFFECTS OF INTERNAL LOADING ON ALGAL BIOMASS IN LAKE ALLATOONA, A SOUTHEASTERN PIEDMONT IMPOUNDMENT by Elena Louise Ceballos (Under the direction of Todd C. Rasmussen) Abstract Cultural eutrophication of lakes is the accelerated nutrient enrichment resulting in detri- mental ecological effects such as algal blooms, lake anoxia and toxic metal release from sediments. Cultural eutrophication is a common occurrence in Piedmont impoundments in Georgia, as well as lakes and impoundments throughout the world. It often results in water unsafe for agricultural use, recreation and drinking. To reduce the cultural eutrophication of local Piedmont impoundments, recent regulatory controls for nutrients were established as part of the Clean Lakes program and court-ordered total maximum daily loads (TMDLs). These regulatory efforts focus on the reduction and minimization of point-source watershed nutrient inputs, primarily phosphorus, into lake sys- tems, as P is the limiting nutrient in Piedmont impoundments. Thus, reductions in phos- phorus loading are expected to improve lake water quality. However, in the Piedmont, as well as worldwide, many lakes continue to experience algal blooms and lake anoxia after sources of external loading are discontinued. The process of nutrient desorption from sediments, known as internal loading, has been identified to be a source of algal-available P, as well as other nutrients. The conditions under which internal loading takes place are region-specific as they vary based on local physical, chemical and biological conditions. The purpose of our research was to quantify changes in algal biomass in response to internal loading in Southeast Piedmont impoundments. The results from a mesocosm exper- iment, physical and chemical sediment analysis, and algal assays were used to characterize algal-availabile phosphorus in Southeastern Piedmont impoundments. -

Georgia Library Quarterly, Spring 2007 Susan Cooley [email protected]

Georgia Library Quarterly Volume 44 | Issue 1 Article 36 April 2007 Georgia Library Quarterly, Spring 2007 Susan Cooley [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Cooley, Susan (2007) "Georgia Library Quarterly, Spring 2007," Georgia Library Quarterly: Vol. 44 : Iss. 1 , Article 36. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq/vol44/iss1/36 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia Library Quarterly by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cooley: Georgia Library Quarterly, Spring 2007 Volume 44 Number 1 Spring 2007 Published by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University, 2007 1 Georgia Library Quarterly, Vol. 44, Iss. 1 [2007], Art. 36 https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/glq/vol44/iss1/36 2 Cooley: Georgia Library Quarterly, Spring 2007 The Official Journal From the President by JoEllen Ostendorf 2 of the Georgia Library Association My Own Private Library by Dusty Gres 4 Volume 44, Number 1 Spring 2007 Getting on Your Community’s 5 Leadership Team By Ellen G. Miller and Patricia H. Fisher Paper Recycling and Academic Libraries 9 A COMO White Paper by Jack R. Fisher II and Elaine Yontz Library Tools for Connecting With the 14 Subscription Rates: $25.00 per year Curriculum: How To Create a Professional free to GLA members Development Workshop for Teaching Faculty Microfilm copies of back by Sonya S. Shepherd, Debra Skinner issues of GLQ may be and Robert W. -

A D U Lt T R

CLOUDLAND CANYON BRAVES GAME Located on the western edge of Lookout Mountain, Come join us as we head out to the new ballpark, Cloudland Canyon is one of the largest and most scenic SunTrust Park, to cheer on the Atlanta Braves! They will parks in the state. Home to thousand-foot deep canyon, be playing against the Pittsburgh Pirates. Play ball! sandstone cliffs, wild caves, waterfalls, cascading creeks, dense woodland and abundant wildlife, the park offers Day: Thursday ample outdoor recreation opportunities. Wear your Date: May 25 Course Code: 17418 comfortable hiking shoes because we are going to Time: 10:00 a.m. explore the sites. We might do the overlook trail, or the Fee: TBA western loop trail. Come with us as we take a hike and Age: Adult explore natures beauty. Location: Atlanta Day: Tuesday BRASSTOWN BALD Date: May 2 Course Code: 17415 Brasstown Bald, Georgia, rising 4,784 feet about sea level, Time: 7:30 a.m. is Georgia’s tallest mountain. Its incredible 360 degree Fee: $10 (resident) $15 (non-resident) view allows you to see Georgia, North Carolina, Age: Adult Tennessee, and South Carolina on a clear day. We will Location: Rising Fawn also have the opportunity to shop at their unique gift shop, tour the visitors center that focuses on Georgia History, geology and the natural world, and see a short movie about the incredible changes to the Brasstown landscape DOWNTOWN DECATUR FOOD TOUR during the years. Come with us as we travel to north ADULT TRIPS ADULT Come with us as we travel to Decatur for a food tour.