The Five Stages of Grief in Horace's Ode I.24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smith Family…

BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO. UTAH Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/smithfamilybeingOOread ^5 .9* THE SMITH FAMILY BEING A POPULAR ACCOUNT OF MOST BRANCHES OF THE NAME—HOWEVER SPELT—FROM THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY DOWNWARDS, WITH NUMEROUS PEDIGREES NOW PUBLISHED FOR THE FIRST TIME COMPTON READE, M.A. MAGDALEN COLLEGE, OXFORD \ RECTOR OP KZNCHESTER AND VICAR Or BRIDGE 50LLARS. AUTHOR OP "A RECORD OP THE REDEt," " UH8RA CCELI, " CHARLES READS, D.C.L. I A MEMOIR," ETC ETC *w POPULAR EDITION LONDON ELLIOT STOCK 62 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. 1904 OLD 8. LEE LIBRARY 6KIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY PROVO UTAH TO GEORGE W. MARSHALL, ESQ., LL.D. ROUGE CROIX PURSUIVANT-AT-ARM3, LORD OF THE MANOR AND PATRON OP SARNESFIELD, THE ABLEST AND MOST COURTEOUS OP LIVING GENEALOGISTS WITH THE CORDIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENTS OP THE COMPILER CONTENTS CHAPTER I. MEDLEVAL SMITHS 1 II. THE HERALDS' VISITATIONS 9 III. THE ELKINGTON LINE . 46 IV. THE WEST COUNTRY SMITHS—THE SMITH- MARRIOTTS, BARTS 53 V. THE CARRINGTONS AND CARINGTONS—EARL CARRINGTON — LORD PAUNCEFOTE — SMYTHES, BARTS. —BROMLEYS, BARTS., ETC 66 96 VI. ENGLISH PEDIGREES . vii. English pedigrees—continued 123 VIII. SCOTTISH PEDIGREES 176 IX IRISH PEDIGREES 182 X. CELEBRITIES OF THE NAME 200 265 INDEX (1) TO PEDIGREES .... INDEX (2) OF PRINCIPAL NAMES AND PLACES 268 PREFACE I lay claim to be the first to produce a popular work of genealogy. By "popular" I mean one that rises superior to the limits of class or caste, and presents the lineage of the fanner or trades- man side by side with that of the nobleman or squire. -

On the Nationalisation of the Old English Universities

TH E NATIONALIZATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES LEWIS CAMPBELL, MA.LLD. /.» l.ibris K . DGDEN THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES J HALL & SON, Be> • ON THE NATIONALISATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES ON THE NATIONALISATION OF THE OLD ENGLISH UNIVERSITIES BY LEWIS CAMPBELL, M.A., LL.D. EMERITUS PKOFESSOK OF GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. ANDREWS HONORARY FELLOW OF BALLIOL COLLEGE, OXFORD LONDON: CHAPMAN AND HALL 1901 LK TO CHARLES SAVILE ROUNDELL My dear Roundell, You have truly spoken of the Act, which forms the central subject of this book, as " a little measure that may boast great things." To you, more than to anyone now living, the success of that measure was due ; and without your help its progress could not here have been set forth. To you, therefore, as of right, the following pages are in- scribed. Yours very sincerely, LEWIS CAMPBELL PREFACE IN preparing the first volume of the Life of Benjamin fowett, I had access to documents which threw unexpected light on certain movements, especially in connexion with Oxford University- Reform. I was thus enabled to meet the desire of friends, by writing an article on " Some Liberal Move- ments of the Last Half-century," which appeared in the Fortnightly Review for March, 1900. And I was encouraged by the reception which that article met with, to expand the substance of it into a small book. Hence the present work. I have extended my reading on the subject, and have had recourse to all sources of information which I found available. -

Good Men and True

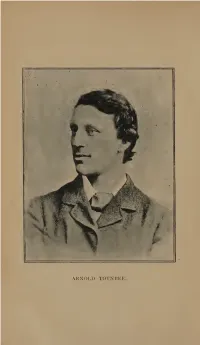

ARNOLD TOYNBEE. GOOD MEN AND TRUE BIOGRAPHIES OF WORKERS IN THE FIELDS OF BENEFICENCE AND BENEVOLENCE BY ALEXANDER H. JAPP, LL.D. AUTHOR OF “ GOLDEN LIVES,” “MASTER MISSIONARIES," “LIFE OF THOREAU,'' ETC.,’ ETC. SECOND EDITION. T. FISHER UNWIN TATERNOSTER SQUARE 1890 “ Men resemble the gods in nothing so much as in doing good to their fellow-creature—man.”—Cicero. 112053 3 1223 00618 4320 MY LITTLE FRIENDS AND CORRESPONDENTS, TOM, CARL, AND ANNE, GRANDCHILDREN OF THOMAS GUTHRIE, D.D., IN THE HOPE THAT THEY MAY NOT BE WHOLLY DISAPPOINTED WITH THE LITTLE SKETCH I HAVE, IN THIS VOLUME, TRIED TO MAKE OF THEIR REVERED GRANDFATHER, PARTLY FROM THE MEMOIR OF THEIR FATHER AND UNCLE, AND PARTLY FROM IMPRESSIONS OF MY OWN. Oh, young in years, in heart, and hope. May ye of lives like his be led. And find new courage, strength, and scope, In thoughts of him each step ye tread: And draw the line op goodness down Through long descent, to be your crown— A crown the greener that its roots are laid Deep in the past in fields your forbears made. CONTENTS. I PAGE NORMAN MACLEOD, D.D., preacljcr aim Unitor. 13 11. EDWARD DENISON, <£ast=<£nD CCIorLcr aim Social Reformer. 105 hi. ARNOLD TOYNBEE, Christian economist anti Klotiiers’ jFjctenl). 139 ,iv. JOHN CONINGTON, £*)djoIar aim Christian Socialist. 175 v. CHARLES KINGSLEY, Christian Pastor ann /Bofcefist. 197 IO CONTENTS. PAGE VI. JAMES HANNINGTON, SSiggtotiarp 'Bishop attn Crabeiier. 239 VII. THE STANLEYS—FATHER AND SON : Ecclesiastics ann IReformcrgs. 271 VIII. THOMAS GUTHRIE, D.D., Preacher ann jFounDer of 3Rag;gen Schools in Eninlntrgh- 311 IX. -

For Syria with the Sixth Legion-His Cavalry Is Not Referred to (33). In

for Syria with the sixth legion-his cavalry is not referred to (33). In describing the battle of Domitius against Pharnaces, the author neglects to mention the disposition of the Roman cavalry (38-9). There is no report of the cavalry action in the battle of Zela (75 ff.). The cavalry is neglected in the important evaluation of the troops by Caesar in Pontus (69). The pattern, sometimes subtle, is unmistakable. Caesar and the subsequent authors of the civil wars, displaying traditional Roman neglect of the cavalry, at times overlook this arm in their reports of military actions. The cavalry was regarded as an unfortunate necessity generally posing more problems than the more disciplined, polished, and effectively trained legionary soldiers.6 The author of the de bello Hispaniensi reverses this pattern and provides detailed information about the cavalry and, more than this, is proud of its effectiveness in Spain.7 For this reason it seems logical to suggest that the author of the Spanish War was connected with the cavalry in a leadership capacity such as praefectus equitum?B University of Maryland, Baltimore County R. H. STORCH 6. The composition of Caesar's cavalry: 0. Schambach, Die Reiterei bei Caesar (Miihlhausen, 1881), p. 7 ff. 7. B. Hisp. 7, 15. 8. It is well-known (Holmes, Rom. Rep., p. 298) that the author of the Spanish War had an abysmal lack of knowledge about important aspects of the campaign (e.g. the purpose of certain operations). As praefectus equitum he would not have bee n an important member of Caesar's staff. -

Vergil's Aeneid and Homer Georg Nicolaus Knauer

Vergil's "Aeneid" and Homer Knauer, Georg Nicolaus Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1964; 5, 2; ProQuest pg. 61 Vergil's Aeneid and Homer Georg Nicolaus Knauer FTEN since Vergil's Aeneid was edited by Varius and Plotius O Tucca immediately after the poet's death (18/17 B.C.) and Propertius wrote his (2.34.6Sf) cedite Romani scriptores, cedite Grat, nescio qUid maius nascitur Iliade Make way, ye Roman authors, clear the street, 0 ye Greeks, For a much larger Iliad is in the course of construction (Ezra Pound, 1917) scholars, literary critics and poets have tried to define the relation between the Aeneid and the Iliad and Odyssey. As one knows, the problem was not only the recovery of details and smaller or larger Homeric passages which Vergil had used as the poet ical background of his poem. Men have also tried from the very be ginning, as Propertius proves, to evaluate the literary qualities of the three respective poems: had Vergil merely stolen from Homer and all his other predecessors (unfortunately the furta of Perellius Faustus have not come down to us), is Vergil's opus a mere imitation of his greater forerunner, an imitation in the modern pejorative sense, or has Vergil' s poetic, philosophical, even "theological" strength sur passed Homer's? Was he-not Homer-the maximus poetarum, divinissimus Maro (Cerda)? For a long time Vergil's ars was preferred to Homer's natura, which following Julius Caesar Scaliger one took to be chaotic, a moles rudis et indigesta (Cerda, following Ovid Nlet. -

Poets, Poems, Poetics

Cunningham_cover.indd 1 5/26/2011 6:38:25 PM CCunningham_ffirs.inddunningham_ffirs.indd iiii 55/16/2011/16/2011 11:13:40:13:40 PPMM Victorian Poetry Now CCunningham_ffirs.inddunningham_ffirs.indd i 55/16/2011/16/2011 11:13:39:13:39 PPMM CCunningham_ffirs.inddunningham_ffirs.indd iiii 55/16/2011/16/2011 11:13:40:13:40 PPMM Victorian Poetry Now Poets, Poems, Poetics Valentine Cunningham A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication CCunningham_ffirs.inddunningham_ffirs.indd iiiiii 55/16/2011/16/2011 11:13:40:13:40 PPMM This edition fi rst published 2011 © 2011 Valentine Cunningham Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Offi ce John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offi ces 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Valentine Cunningham to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Early Modern and Modern Commentaries on Virgil

EARLY MODERN AND MODERN COMMENTARIES ON VIRGIL JUNE 14-16, 2021 An online conference Link Zoom: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/81909339883 All times are CEST (Rome time). For more information: [email protected] EARLY MODERN AND MODERN COMMENTARIES ON VIRGIL Monday, June 14, 2pm-2:20pm Welcoming words by EMORE PAOLI (Director of the Department of Studi letterari, filosofici e di storia dell’arte, Università di Roma “Tor Vergata”) and introduction by SERGIO CASALI SESSI SESSION 1 ON 1 Monday, June 14, 2:20pm-5pm Chair: VIRGILIO COSTA Università di Roma “Tor Vergata” DAVID WILSON-OKAMURA East Carolina University Afterimages of Lucretius FABIO STOK Università di Roma “Tor Vergata” Commenting on Virgil in the 15th Century: from Barzizza (?) to Parrasio (?)-I GIANCARLO ABBAMONTE Università di Napoli Federico II Commenting on Virgil in the 15th Century: from Barzizza (?) to Parrasio (?)-II NICOLA LANZARONE Università di Salerno Il commento di Pomponio Leto all’Eneide: sondaggi relativi ad Aen. 1 e 2 SESSION 2 Monday, June 14, 5:20pm-8pm Chair: EMANUELE DETTORI Università di Roma “Tor Vergata” PETER KNOX Case Western Reserve University What if Poliziano Had Written a Commentary on Virgil? PAUL WHITE University of Leeds Badius’s Virgil Commentary in the Context of Humanist Education ANDREA CUCCHIARELLI Sapienza Università di Roma Petrus Nannius as an Interpreter of Virgil: the Commentary on the Eclogues SERGIO CASALI Università di Roma “Tor Vergata” Petrus Nannius as an Interpreter of Virgil: the Commentary on Aeneid 4 EARLY MODERN AND MODERN COMMENTARIES ON VIRGIL SESSION 3 Tuesday, June 15, 2pm-4:40pm Chair: JOHN F. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-01195-2 - P. Vergili Maronis Opera, Volume 1 Edited by John Conington Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE LIBRARY COLLECTION Books of enduring scholarly value Classics From the Renaissance to the nineteenth century, Latin and Greek were compulsory subjects in almost all European universities, and most early modern scholars published their research and conducted international correspondence in Latin. Latin had continued in use in Western Europe long after the fall of the Roman empire as the lingua franca of the educated classes and of law, diplomacy, religion and university teaching. The flight of Greek scholars to the West after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 gave impetus to the study of ancient Greek literature and the Greek New Testament. Eventually, just as nineteenth-century reforms of university curricula were beginning to erode this ascendancy, developments in textual criticism and linguistic analysis, and new ways of studying ancient societies, especially archaeology, led to renewed enthusiasm for the Classics. This collection offers works of criticism, interpretation and synthesis by the outstanding scholars of the nineteenth century. P. Vergili Maronis Opera First published between 1858 and 1871, John Conington’s lucid exposition of the complete works of Virgil continues to set the standard for commentary on the Virgilian corpus. After decades out of print, this three-volume edition is once again available to readers, allowing Conington’s subtle investigations of language, context, and intellectual background to find a fresh audience. Volume 1 features the Eclogues and Georgics. Introductory essays and detailed, informative notes situate the individual works within the larger field of Latin pastoral and didactic poetry. -

Who Would Keep an Ancient Form?": in Memoriam and the Metrical Ghost of Horace

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2010-11-18 "Who Would Keep an Ancient Form?": In Memoriam and the Metrical Ghost of Horace Ryan D. Stewart Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Stewart, Ryan D., ""Who Would Keep an Ancient Form?": In Memoriam and the Metrical Ghost of Horace" (2010). Theses and Dissertations. 2440. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/2440 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ―Who Would Keep an Ancient Form?‖: In Memoriam and the Metrical Ghost of Horace Ryan D. Stewart A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts John Talbot, Chair Leslee Thorne-Murphy Kimberly Johnson Department of English Brigham Young University December 2010 Copyright © 2010 Ryan D. Stewart All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT ―Who Would Keep an Ancient Form?‖: In Memoriam and the Metrical Ghost of Horace Ryan D. Stewart Department of English Master of Arts Although Alfred Tennyson‘s 1850 elegy, In Memoriam, has long been regarded for the quality of its grief and its doubt, the deepened sense of struggle and doubt produced by his allusions to Horace in both the matter and the meter of the poem have not been considered. -

Alt Context 1861-1896

1861 – Context – 168 Agnes Martin; or, the fall of Cardinal Wolsey. / Martin, Agnes.-- 8o..-- London, Oxford [printed], [1861]. Held by: British Library The Agriculture of Berkshire. / Clutterbuck, James Charles.-- pp. 44. ; 8o..-- London; Slatter & Rose: Oxford : Weale; Bell & Daldy, 1861. Held by: British Library Analysis of the history of England, (from William Ist to Henry VIIth,) with references to Hallam, Guizot, Gibbon, Blackstone, &c., and a series of questions / Fitz-Wygram, Loftus, S.C.L.-- Second ed.-- 12mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland An Answer to F. Temple's Essay on "the Education of the World." By a Working Man. / Temple, Frederick, Successively Bishop of Exeter and of London, and Archbishop of Canterbury.-- 12o..-- Oxford, 1861. Held by: British Library Answer to Professor Stanley's strictures / Pusey, E. B. (Edward Bouverie), 1800-1882.-- 6 p ; 22 cm.-- [Oxford] : [s.n.], [1861] Notes: Caption title.-- Signed: E.B. Pusey Held by: Oxford Are Brutes immortal? An enquiry, conducted mainly by the light of nature into Bishop Butler's hypotheses and concessions on the subject, as given in part 1. chap. 1. of his "Analogy of Religion." / Boyce, John Cox ; Butler, Joseph, successively Bishop of Bristol and of Durham.-- pp. 70. ; 8o..-- Oxford; Thomas Turner: Boroughbridge : J. H. & J. Parker, 1861. Held by: British Library Aristophanous Ippes. The Knights of Aristophanes / with short English notes [by D.W. Turner] for the use of schools.-- 56, 58 p ; 16mo.-- Oxford, 1861 Held by: National Library of Scotland Arnold Prize Essay, 1861. The Christians in Rome during the first three centuries. -

0501002A Proceedings 188205

L I B RAR.Y OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AM 1881-85 material is re- The person charging this return on or before the sponsible for its Latest Date stamped below. of books Theft, mutilation, and underlining and are reasons for disciplinary action may result in dismissal from the University. University of Illinois Library IL27 L161 O-1096 152 THE LIBRARY JOURNAL. BOOKS OF VALUE Charles Sumner's Works. Higginson's Works. all his Public Orations and vol- Containing Speeches. 15 ARMY LIFE IN A BLACK REGIMENT. $1.50 umes. Per volume, cloth, $3.00; half-calf, $5.00. Sold ATLANTIC ESSAYS 1.50 only by subscription. Volumes I. to XIII. now ready. OLDPORT DAYS. With 10 Heliotype Illustrations. 2.00 Wendell Phillips's Speeches, MALBONE. AN OLDPORT ROMANCE. 1.50 OUTDOOR PAPERS. Lectures, and Letters.* ,. 1.50 YOUNG FOLKS' HISTORY OF THE UNITED Cloth, $2.50. Illustrated * STATES. 1.50 A new volume may be expected this containing later faljp YOUNG FOLKS' BOOK OF AMERICAN EX- Speeches and Lectures. PLORERS. Illustrated. .1.50 Warrington's Pen Portraits. SHORT STUDIES OF AMERICAN AUTHORS. Little Classic size. ... .75 A collection of Personal and Political Reminiscences, from 1848 to 1876. From the Writings of WILLIAM S. ROBIN- SON, with Memoir, and Extracts from Diary and Letters Books of Travel. never before published. Edited by Mrs. W. S. ROBINSON. Crown 8vo, cloth, $2.50. By NATHANIEL H. BISHOP. A THOUSAND MILES' WALK ACROSS SOUTH George H. Calvert's Works. AMERICA, OVER THE PAMPAS AND THE ANDES. Illustrated, cloth, $1.50. ESSAYS .ESTHETICAL. -

History of Latin Literature I: the Republic 190:677 Fall 2009 Mon, Thurs 4:00-5:20 Pm Ruth Adams Building 003, DC

History of Latin Literature I: The Republic 190:677 Fall 2009 Mon, Thurs 4:00-5:20 pm Ruth Adams Building 003, DC Leah Kronenberg Ruth Adams Bldg. 006 (DC) Department of Classics 732-932-9600 Office Hours: Thursdays 3-4 pm and by appt [email protected] Course Description This course will provide a general history of Latin literature from its beginnings in the 3rd century B.C. to its flourishing in the Late Republic (1st century B.C.), a time period which includes most of the great works from the so-called “Golden Age” of Latin literature. Authors covered include, Plautus, Terence, Caesar, Cicero, Sallust, Catullus, Lucretius, Livy, Horace, Propertius, Tibullus, and Virgil. Some of the major themes we will cover include the Romans’ attitude towards Greek literature and their development of a self-conscious national literature; the originality of Latin literature and its creative use of genre and allusion; and the complex interaction between literature and politics during the breakdown of the Roman Republic. Course Goals Improve your Latin translation skills by reading large quantities of Latin Prepare for the MA and PhD general exams in Latin literature Gain an understanding of the development of Latin literature from its beginnings through Virgil Learn about the Greek background to Latin literature as well as the many ways in which Latin literature distinguishes itself from the Greek Place Latin literature in its cultural and historical context Investigate the different genres of Latin literature Course Website The course website is accessible through the Sakai homepage. Go to https://sakai.rutgers.edu and follow the instructions for logging in as a student.