Sheffield Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval Pottery from Romsey: an Overview

Proc. Hampshire Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 67 (pt. II), 2012, 323–346 (Hampshire Studies 2012) MEDIEVAL POTTERY FROM ROMSEY: AN OVERVIEW By BEN JERVIS ABSTRACT is evidence of both prehistoric and Roman occupation, but this paper will deal only with This paper summarises the medieval pottery recovered the medieval archaeology, from the mid-Saxon from excavations undertaken by Test Valley Archae- period to the 16th century. ological Trust in Romsey, Hampshire from the Several excavations took place between the 1970’s–1990’s. A brief synthesis of the archaeology of 1970’s–90’s in the precinct of Romsey Abbey Romsey is presented followed by a dated catalogue of (see Scott 1996). It has been suggested on the pottery types identified, including discussions of the basis of historical evidence and a series fabric, form and wider affinities. The paper concludes of excavated, early, graves that the late Saxon with discussions of the supply of pottery to Romsey in abbey was built on the site of an existing eccle- the medieval period and also considers ceramic use siastical establishment, possibly a minster in the town. church (Collier 1990, 45; Scott 1996, 7). The foundation of the nunnery itself can be dated to the 10th century (Scott 1996, 158), but it INTRODUCTION was evacuated in AD 1001, due to the threat of Danish attack, being re-founded later in The small town of Romsey has been the focus the 11th century. The abbey expanded during of much archaeological excavation over the last the Norman period, with the building of the 30–40 years, but very little has been published choir and nave (Scott 1996, 7). -

Bulletin N U M B E R 3 2 0 May/June 1998

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Tel/Fax: 01483 532454 E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin N u m b e r 3 2 0 May/June 1998 BRONZE AGE HUT FOUND AT LALEHAM Post-built round house, looking north-west through its entrance. Preliminary work on the finds suggest a date in the late 2nd millennium BC. Ranging Rods marl<ed in 0.20m divisions, but ttie director, Graham t-iayman, provides a human scale whilst demonstrating his understanding of contemporary folk-dancing. Excavations at Home Farm, Laleham in 1997 Graham Hayman In May and June of last year the Surrey County Archaeological Unit undertook excavations at Home Farm, Laleham, for Greenham Construction Materials Ltd, as part of an archaeological scheme of work approved to comply with the conditions of a Planning Permission for the extraction of gravel. Home Farm Quarry Is being worked In phases over several years, with each phase area being restored to Its agricultural purposes once quarrying Is completed. Work in 1997 was in the Phase 6 area and proceeded as a result of discoveries made during an evaluation by trenching in March 1997. Five areas A to E were excavated. Areas A to C in the south revealed occasional small pits and post-holes, two large water-holes, various ditches, and at least two cremation burials. Most features were sparsely distributed, however, with no significant concentrations; and produced only a few pot sherds and/or pieces of struck flint. Such a paucity of finds made it difficult to date some features, but a provisional assessment is that most were of Bronze Age date, some may be Neolithic, and at least one ditch was probably Roman. -

Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd

T H A M E S V A L L E Y ARCHAEOLOGICAL S E R V I C E S 14–16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire An Archaeological Watching Brief by Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Site Code: MLB06/65 (SU 6675 5302) 14-16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire An Archaeological Watching Brief For Dr Weaver & Partners by Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd Site Code MLB 06/65 December 2006 Summary Site name: 14-16 Milkingpen Lane, Old Basing, Basingstoke, Hampshire Grid reference: SU6675 5302 Site activity: Watching Brief Date and duration of project: 19th July – 21st August 2006 Project manager: Steve Ford Site supervisor: Jennifer Lowe and Sean Wallis Site code: MLB06/65 Area of site: 2688 sq m Summary of results: The watching brief revealed a moderate quantity of archaeological features including ditches, gullies, several pits and a square structure. The majority of features encountered suggested activity on the site during the 13th century with later activity, mid 16th-17th century, in the form of a ditch. Three sherds of residual Romano-British pottery were also recovered during the course of the works. Monuments identified: Medieval pits, ditches, square structure. Post-medieval ditch. Location and reference of archive: The archive is presently held at Thames Valley Archaeological Services, Reading and will be deposited Hampshire Museum Service in due course. This report may be copied for bona fide research or planning purposes without the explicit permission of the copyright holder Report edited/checked by: Steve Ford 21.12.06 Steve Preston 21.12.06 i Thames Valley Archaeological Services Ltd, 47–49 De Beauvoir Road, Reading RG1 5NR Tel. -

Surrey-Hampshire Border Ware Ceramics in Seventeenth-Century

SURREY-HAMPSHIRE BORDER WARE CERAMICS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH NORTH AMERICA by © Catherine Margaret Hawkins A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland April 2016 St. John’s Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Surrey-Hampshire Border ware ceramics were among of the most popular and widely used ceramics in southern England. This ceramic, produced along the Surrey-Hampshire border, was also shipped to English colonies in North America throughout the seventeenth century. This thesis will explore the types of vessels uncovered on archaeological sites in Newfoundland, New England and the Chesapeake, and examine the similarities and differences in the forms available to various colonists during this time period. By comparing the collections of Border ware found at various sites it is possible to not only determine what vessel forms are present in Northeastern English North America, but to determine the similarities and differences in vessels based on temporal, geographic, social or economic factors. A comparative study of Border ware also provides information on the socio- economic status of the colonists and on trading networks between England and North America during the seventeenth century. i Acknowledgements Grateful thanks are due first and foremost to my supervisor, Dr. Barry Gaulton, for everything he has done for me over the years. My interest in historical archaeology originated through working with Barry and Dr. Jim Tuck at Ferryland several years ago and I cannot thank him enough for his continued support, enthusiasm, advice and encouragement throughout the course of this research project. -

MEDIEVAL POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP Newsletter 74 November 2012 ______

MEDIEVAL POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP newsletter 74 November 2012 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Secretary’s Notes Council met in September at the British Museum had held some very constructive discussions about the future directions which the group’s activities may take. Two topics dominated the agenda, the first of these was training. Alice Forward has undertaken some research into the kinds of specialist and non-specialist training currently available and which might be offered by the group in the future. We welcome any comments from members regarding the kinds of training which you would find useful and any comments on this subject should be addressed to the president. The second issue relates to the maintaining of standards, particularly within reports produced from developer-led projects. Central to this is co-operation with our Prehistoric and Roman colleagues in the production of joint standards, which can be easily disseminated to local authority curators. A need for non-specialist training into these standards was identified and we will be pursuing this with our colleagues within the curatorial sector going forward. In November members of the group came together with colleagues from the Association for the History of Glass at a conference held in honour of the late Sarah Jennings. Unfortunately I was unable to attend, but I hear from colleagues that this day was a great success and, more importantly, a fitting tribute to Sarah. Thanks are extended to Julie Edwards and Sarah Paynter for their hard work in organising the conference, and in pushing forward with plans for a festschrift in Sarah’s memory. Additionally, Chris Jarrett is continuing to work on a similar publication in honour of Anna Slowikowski. -

Doncaster to Conisbrough (PDF)

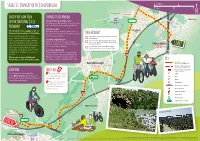

Kilometres 0 Miles 0.5 1 1.5 0 Kilometres 1 Stage 17: Doncaster to Conisbrough A638 0 Miles 0.5 1 Cusworth To Selby River Don Enjoy the Slow Tour Things to see and do Wheatley Cusworth Hall and Museum A Cusworth 19 on the National Cycle An imposing 18th century country house Hall set in extensive landscaped parklands. 30 Network! A6 Sprotborough A638 Richmond The Slow Tour is a guide to 21 of Sprotborough is a village which sits on Hill the best cycle routes in Yorkshire. the River Don and has locks which allow Take a Break! It’s been inspired by the Tour de boats to pass safely. Doncaster has plenty of cafés, pubs and restaurants. France Grand Départ in Yorkshire in A 1 Conisbrough Viaduct (M Doncaster ) 2014 and funded by Public Health The Boat Inn, Sprotborough does great A630 With its 21 arches the grand viaduct Teams in the region. All routes form food and is where Sir Walter Scott wrote spans the River Don and formed part of his novel Ivanhoe. Doncaster part of the National Cycle Network - start the Dearne Valley Railway. The Red Lion, Conisbrough is a Sam more than 14,000 miles of traffic- Smith pub and serves a range of food. River Don free paths, quiet lanes and on-road Conisbrough Castle A638 walking and cycling routes across This medieval fortification was initially the UK. built in the 11th century by William de Hyde Warenne, the Earl of Surrey, after the Park This route is part of National Hexthorpe A18 0 Norman conquest of England in 1066. -

The Castle Studies Group Bulletin

THE CASTLE STUDIES GROUP BULLETIN Volume 17 April 2014 Editorial INSIDE THIS ISSUE amela Marshall, the Chair and Secretary of the Castle Studies Group has Pdecided, after serving in the role for 14 years, to step down at the next News Ireland AGM in April. During that period Pamela has given so much of her time to CSG Limerick/Coolbanagher/ affairs not only for the benefit of the CSG membership directly but also has Carrickfergus represented us on the international stage. Her election to the Comité Perma- 2-3 nent of the Château-Gaillard Colloque at about the same time allowed those links between that august body and the CSG to be strengthened for the benefit Diary Dates of castle studies more widely. I am sure all of us would wish to thank Pamela 4-5 for steering and guiding the CSG over the past 14 years but also look forward to her continuing contribution to castle research and publication. News England The successor to Pamela, who after Bob Higham, will be only the third At Risk Register/ elected Chair in the history of the group, is now being sought. Nominations for Lancaster Castle the new Chair are being considered and will form part of the discussion at the 6-8 forthcoming AGM to be held during the CSG Ulster conference in Belfast on April 26 2014. It is expected that members will have an opportunity to vote for More News Ireland the new Chair but to give due consideration and an appropriate period of con- Ballinskelligs/Limerick sultation, an interim or caretaker Chair may be necessary in the short term. -

Alaris Capture Pro Software

- The Battle of Wakefield and the Wars of the Roses KEITH DOCKRAY THE BA'ITLE 0F WAKEFIELD,fought on 30 December 1460 (almost certainly, and unusually, during the afternoon), was the fifth of about fifteen set-piece military confrontations that punctuated the so-called War's of the Roses between 1455 and 1487. The most serious and protracted civil wars England had experienced since the Norman Conquest, their origins can be fou‘nd mainly in the political turmoil occasioned by the disastrous rule of the third Lancastrian King Henry VI (1422-1461). In particular, the King’s simplicity of mind and pathetically trusting nature left him fatally vulnerable to grasping favourites and unscrupulous ministers: even in the 1440s and early 1450s, when he remained more or less compos menu's, it was bad enough; once he had suffered a complete mental breakdown in 1453, from which he probably never completely recovered, his shortcomings became ever more evident and he was certainly incapable of containing the mounting baronial rivalries that eventually culminated in out- and-out civil war.1 Ever since he had attained his majority in 1437, Henry VI’s failure to control royal patronage judiciously had encouraged baronial jealousy and resentment. In particular, since the late 1440s, there had developed an increasingly bitter personal rivalry between Richard Plantagenet Duke of York, the most powerful magnate in the land (who also happened to have a strong claim to the 'throne), and Edmund Beaufort Duke of Somerset who, despite bearing a good deal of responsibility for the loss of virtually all England’s possessions in France by the autumn of 1453, enjoyed more than his fair share of the fruits of royal favour in the early 14505. -

Conisbrough Circular Walk ‘Castles and Crossings’

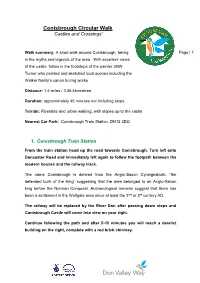

Conisbrough Circular Walk ‘Castles and Crossings’ Walk summary: A short walk around Conisbrough, taking Page | 1 in the myths and legends of the area. With excellent views of the castle, follow in the footsteps of the painter JMW Turner who painted and sketched local scenes including the Walker family’s canon boring works Distance: 1.5 miles / 2.35 kilometres Duration: approximately 45 minutes not including stops Terrain: Riverside and urban walking, with slopes up to the castle Nearest Car Park: Conisbrough Train Station, DN12 3DQ 1. Conisbrough Train Station From the train station head up the road towards Conisbrough. Turn left onto Doncaster Road and immediately left again to follow the footpath between the modern houses and the railway track. The name Conisbrough is derived from the Anglo-Saxon Cyningesburh, “the defended burh of the King” suggesting that the area belonged to an Anglo-Saxon king before the Norman Conquest. Archaeological remains suggest that there has been a settlement in the Wellgate area since at least the 2nd or 3rd century AD. The railway will be replaced by the River Don after passing down steps and Conisbrough Castle will come into view on your right. Continue following the path and after 5-10 minutes you will reach a derelict building on the right, complete with a red brick chimney. 2. Ferry Farm Ferry Farm has traditionally been owned by the controller of the ferryboat that crossed the Don here. The first record of there being a ferryboat present was in 1319 when ferry was operated by a man known as Henry the ferryman. -

Download William Jenyns' Ordinary, Pdf, 1341 KB

William Jenyns’ Ordinary An ordinary of arms collated during the reign of Edward III Preliminary edition by Steen Clemmensen from (a) London, College of Arms Jenyn’s Ordinary (b) London, Society of Antiquaries Ms.664/9 roll 26 Foreword 2 Introduction 2 The manuscripts 3 Families with many items 5 Figure 7 William Jenyns’ Ordinary, with comments 8 References 172 Index of names 180 Ordinary of arms 187 © 2008, Steen Clemmensen, Farum, Denmark FOREWORD The various reasons, not least the several german armorials which were suddenly available, the present work on the William Jenyns Ordinary had to be suspended. As the german armorials turned out to demand more time than expected, I felt that my preliminary efforts on this english armorial should be made available, though much of the analysis is still incomplete. Dr. Paul A. Fox, who kindly made his transcription of the Society of Antiquaries manuscript available, is currently working on a series of articles on this armorial, the first of which appeared in 2008. His transcription and the notices in the DBA was the basis of the current draft, which was supplemented and revised by comparison with the manuscripts in College of Arms and the Society of Antiquaries. The the assistance and hospitality of the College of Arms, their archivist Mr. Robert Yorke, and the Society of Antiquaries is gratefully acknowledged. The date of this armorial is uncertain, and avaits further analysis, including an estimation of the extent to which older armorials supplemented contemporary observations. The reader ought not to be surprised of differences in details between Dr. -

Download Newsletter 78

MEDIEVAL POTTERY RESEARCH GROUP newsletter 78 April 2014 _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Secretary’s Notes Pipkins are red, Stonewares are blue, Your MPRG Council really needs you! Rather than write the usual set of Secretary’s Notes that goes out in advance of an impending MPRG AGM, this time round I thought I would keep it short and sweet and instead direct you to a separate mailing, coming hot on the heels of this Newsletter, which will shed some light on what drives the Secretary to start penning very bad verse! Council met again at the end of January to discuss and drive on the work of the group. These days there is a great deal to cover in meetings with the wide range of work that the Group is involved in, from managing the John Hurst Travel Fund (see this issue for more information) and liaising with the British Museum over improving access to the Alan Vince Archive, through arranging a new set of Specialist Training Courses for 2015 and developing an online type-series database, to producing the next volume of Medieval Ceramics and making out of print copies of Medieval Ceramics available online via Scribe over the next few months (please check the website for updates). This list doesn’t even cover the work to produce a new Occasional Paper on Medieval Roof Furniture and of course the efforts going into arranging this year’s three-day conference in Lisbon (also see this issue for more information). Sadly these days, with the challenges that we face in funding the work we do for the benefit, not only of the membership, but for the whole of the archaeological community, much of our more recent meetings have focused on reducing costs, maximising funds and finding new ways of doing more with less. -

Conisbrough Conservation Area Appraisal

Conisbrough Conservation Area Appraisal www.doncaster.gov.uk/conservationareas Conisbrough Conservation Area Appraisal Index Preface Part I – Appraisal 1. Introduction 2. Location 3. Origins and development of the settlement 4. Prevailing and former uses and the influence on the plan form and building types 5. Archaeological significance of the area 6. Architectural and historic qualities of the buildings 7. Character and relationship of the spaces in the area 8. Traditional building materials and details 9. Negative features 10. Neutral features 11. Condition of buildings 12. Problems, pressures and capacity for change 13. Suggested boundary changes 14. Summary of special interest Part II – Management Proposals 15. Management Proposals Appendices I Useful Information & Contact Details II Listed Buildings III Relevant Policies of the Doncaster Unitary Development Plan IV Community Involvement Maps 1. Origin and Development of Area 2. Positive Features 3. Negative and Neutral Features 4. Views into and out of Conservation Area 2 Preface The guidance contained in this document is provided to assist developers and the general public when submitting planning applications. It supplements and expands upon the Policies and Proposals of the Doncaster Unitary Development Plan (UDP) and the emerging policies that will be contained within the Local Development Framework (LDF). The UDP contains both the strategic and the local planning policies necessary to guide development in Doncaster and is used by the council for development control purposes. At the time of writing this appraisal, the UDP is being reviewed and will ultimately be replaced with the emerging LDF. It is not possible however for the UDP or indeed the future LDF to address in detail all the issues raised by the many types of development.