SAARIAHO Let the Wind Speak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnus Lindberg Al Largo • Cello Concerto No

MAGNUS LINDBERG AL LARGO • CELLO CONCERTO NO. 2 • ERA ANSSI KARTTUNEN FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU MAGNUS LINDBERG (1958) 1 Al largo (2009–10) 24:53 Cello Concerto No. 2 (2013) 20:58 2 I 9:50 3 II 6:09 4 III 4:59 5 Era (2012) 20:19 ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cello (2–4) FINNISH RADIO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA HANNU LINTU, conductor 2 MAGNUS LINDBERG 3 “Though my creative personality and early works were formed from the music of Zimmermann and Xenakis, and a certain anarchy related to rock music of that period, I eventually realised that everything goes back to the foundations of Schoenberg and Stravinsky – how could music ever have taken another road? I see my music now as a synthesis of these elements, combined with what I learned from Grisey and the spectralists, and I detect from Kraft to my latest pieces the same underlying tastes and sense of drama.” – Magnus Lindberg The shift in musical thinking that Magnus Lindberg thus described in December 2012, a few weeks before the premiere of Era, was utter and profound. Lindberg’s composer profile has evolved from his early edgy modernism, “carved in stone” to use his own words, to the softer and more sonorous idiom that he has embraced recently, suggesting a spiritual kinship with late Romanticism and the great masters of the early 20th century. On the other hand, in the same comment Lindberg also mentioned features that have remained constant in his music, including his penchant for drama going back to the early defiantly modernistKraft (1985). -

LORI LAITMAN the Scarlet Letter Libretto by David Mason

AMERICAN OPERA CLASSICS LORI LAITMAN The Scarlet Letter Libretto by David Mason Claycomb • Armstrong MacKenzie • Belcher Knapp • Gawrysiak Opera Colorado Orchestra and Chorus Ari Pelto Lori CD 1 66:18 LAITMAN Act I (b. 1955) 1 Scene I: A Meeting Place 14:47 The Scarlet Letter (2008, rev. 2015–16) (Wilson, Bellingham, Dimmesdale, Chillingworth, Prynne, Chorus) Opera in Two Acts 2 Scene II: The Prison 13:33 (Chillingworth, Prynne) Libretto by David Mason (b. 1954) 3 Interlude: Time Passing 2:29 Based on the novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804–64) (Chorus) Commissioned by The University of Central Arkansas through Robert Holden and the UCA Opera Program 4 Scene III: The Governor’s Rose Garden, Seven Years Later 14:18 (Bellingham, Wilson, Chillingworth, Dimmesdale, Prynne) Cast in order of vocal appearance 5 Scene IV: Dimmesdale’s Study – His Nightmare 21:11 A Sailor . Charles Eaton, Baritone (Chillingworth, Dimmesdale, Hibbons) A Farmer . Benjamin Werley, Tenor Goodwife 1 . Emily Robinson, Soprano John Wilson, an elder minister . Kyle Knapp, Tenor CD 2 45:04 Governor Bellingham . Daniel Belcher, Baritone Arthur Dimmesdale, a young minister . Dominic Armstrong, Tenor Act II Congregation Leader . William Bryan, Baritone 1 Scene I: The Forest 22:33 Goodwife 2 . Becky Bradley, Soprano (Chillingworth, Prynne, Dimmesdale) Goodwife 3 . Danielle Lombardi, Mezzo-soprano Roger Chillingworth, Hester’s long-missing husband . Malcolm MacKenzie, Baritone 2 Scene II: A Meeting Place – Election Day 22:31 Hester Prynne, a young seamstress . Laura Claycomb, Soprano (Hibbons, Prynne, Bellingham, Wilson, Dimmesdale, Chillingworth, Chorus) Mistress Hibbons, a witch . Margaret Gawrysiak, Mezzo-soprano A Shipmaster . William Bryan, Baritone Pearl, Hester’s daughter . -

Amahl and the Night Visitors

Set Design By: Steven C. Kemp AMAHL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS Welcome to Amahl and the Night Visitors! During this exceptional time, it has been a delight for us to bring you the gift of this wonderful holiday show. Created with love, we have brought together a variety of Kansas City’s talented artists to share this story of generosity and hope. It has been so heartwarming to see this production evolve, from the building of the scenery and puppets, to the addition of puppeteers, singers, and the orchestra. I know that it has meant a great deal to all involved to be in a safe space where creativity can flourish and all can practice their craft. The passion and joy of our performers, during this process, has been palpable. I wish you all a happy holiday and hope you enjoy this special show! Deborah Sandler, General Director and CEO BOARD OF TRUSTEES 2020-2021 OFFICERS Joanne Burns, President Tom Whittaker, Vice President Scott Blakesley, Secretary Craig L. Evans, Treasurer BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dr. Ivan Batlle Mira Mdivani Mark Benedict Edward P. Milbank Richard P. Bruening Steve Taylor Tom Butch Benjamin Mann, Counsel Melinda L. Estes, M.D. Karen Fenaroli Michael D. Fields Lafayette J. Ford, III Kenneth V. Hager Niles Jager Amy McAnarney EX-OFFICIO MEMBERS Andrew Garton | Chair, Orpheus KC Mary Leonida | President, Lyric Opera Circle Gigi Rose | Ball Chair, Lyric Opera Circle Dianne Schemm | President, Lyric Opera Guild Presents Amahl and the Night Visitors Opera in one act by Gian Carlo Menotti in order of PRINCIPAL CAST vocal appearance MOTHER Kelly Morel^ AMAHL Holly Ladage KING KASPAR Michael Wu KING MELCHIOR Daniel Belcher KING BALTHAZAR Scott Conner THE PAGE Keith Klein ^Former Resident Artist First Performance: NBC Opera Theatre, New York City, December 24, 1951. -

Houston Grand Opera's 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss's Elektra

Season Update: Houston Grand Opera’s 2017–18 Season Features Long-Awaited Return of Strauss’s Elektra and Bellini’s Norma, World Premiere of Ricky Ian Gordon/Royce Vavrek’s The House without a Christmas Tree, First Major American Opera House Presentation of Bernstein’sWest Side Story Company’s six-year multidisciplinary Seeking the Human Spirit initiative begins with opening production of La traviata Updated July 2017. Please discard previous 2017–18 season information. Houston, July 28, 2017— Houston Grand Opera expands its commitment to broadening the audience for opera with a 2017–18 season that includes the first presentations of Leonard Bernstein’s classic musical West Side Story by a major American opera house and the world premiere of composer Ricky Ian Gordon and librettist Royce Vavrek’s holiday opera The House without a Christmas Tree. HGO will present its first performances in a quarter century of two iconic works: Richard Strauss’s revenge-filled Elektra with virtuoso soprano Christine Goerke in the tempestuous title role and 2016 Richard Tucker Award–winner and HGO Studio alumna Tamara Wilson in her role debut as Chrysothemis, under the baton of HGO Artistic and Music Director Patrick Summers; and Bellini’s grand-scale tragedy Norma showcasing the role debut of stellar dramatic soprano Liudmyla Monastyrska in the notoriously difficult title role, with 2015 Tucker winner and HGO Studio alumna Jamie Barton as Adalgisa. The company will revive its production of Handel’s Julius Caesar set in 1930s Hollywood, featuring the role debuts of star countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo (HGO’s 2017–18 Lynn Wyatt Great Artist) and Houston favorite and HGO Studio alumna soprano Heidi Stober as Caesar and Cleopatra, respectively, also conducted by Maestro Summers; and Rossini’s ever-popular comedy, The Barber of Seville, with a cast that includes the eagerly anticipated return of HGO Studio alumnus Eric Owens, Musical America’s 2017 Vocalist of the Year, as Don Basilio. -

Repertoire and Performance History Virginia Opera Repertoire 1974-2020

Repertoire and Performance History Virginia Opera Repertoire 1974-2020 1974–1975 Initial Projects LA BOHÈME – January 1975 N LA TRAVIATA – June 1975 N 1975–1976 Inaugural Subscription Season TOSCA – October/November 1975 N LUCIA DI LAMMERMOOR – January 1976 N THE BARBER OF SEVILLE – March/April 1976 N 1976–1977 RIGOLETTO – October/November 1976 N IL TROVATORE – January 1977 N THE IMPRESARIO/I PAGLIACCI – March/April 1977 N 1977–1978 MADAMA BUTTERFLY – October/November 1977 N COSÌ FAN TUTTE – January/February 1978 N MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS – American Premiere– April 1978 N 1978–1979 CARMEN – October/November 1978 N THE DAUGHTER OF THE REGIMENT – January 1979 N DON GIOVANNI – March/April 1979 N 1979–1980 LA BOHÈME – October/November 1979 N A CHRISTMAS CAROL – World Premiere – December 1979 N DON PASQUALE – January/February 1980 N THE TALES OF HOFFMAN – March 1980 N 1980–1981 PORGY AND BESS – October/November 1980 N, R HANSEL AND GRETEL – December 1980 N WERTHER – January/February 1981 N I CAPULETI E I MONTECCHI – March/April 1981 N 1981–1982 FAUST – October/November 1981 N CINDERELLA – December 1981 N LA TRAVIATA – January 1982 N THE MAGIC FLUTE – March 1982 N 1982–1983 DIE FLEDERMAUS – October/November 1982 N, R AMAHAL AND THE NIGHT VISITORS – December 1982 N MACBETH – January 1983 N THE ELIXIR OF LOVE – March 1983 N 1983–1984–Inaugural Subscription Season Richmond NORMA – October 1983 R GIANNI SCHICCHI/SUOR ANGELICA – December 1983 R RIGOLETTO – January 1984 N, R THE GIRL OF THE GOLDEN WEST – February/March 1984 N 1984–1985 THE MARRIAGE -

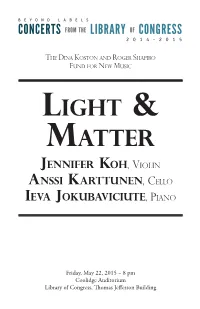

Light & Matter

THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO Friday, May 22, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC Endowed by the late composer and pianist Dina Koston (1929-2009) and her husband, prominent Washington psychiatrist Roger L. Shapiro (1927-2002), the DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO FUND FOR NEW MUSIC supports commissions, contemporary music and its performers. Presented in association with the European Month of Culture Part of National Chamber Music Month Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Friday, May 22, 2015 — 8 pm THE DINA KOSTON AND ROGER SHAPIRO fUND fOR nEW mUSIC LIGHT & MATTER JENNIFER KOH, vIOLIN ANSSI KARTTUNEN, cELLO IEVA JOKUBAVICIUTE, pIANO • Program CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862–1918) Sonate pour Violoncelle et Piano (1915) Prologue: Lent, Sostenuto e molto risoluto–(Agitato)–au Mouvt (largement déclamé)–Rubato–au Mouvt (poco animando)–Lento Sérénade: Modérément animé–Fuoco–Mouvt–Vivace–Meno mosso poco– Rubato–Presque lent–1er Mouvt–au Mouvt– Finale: Animé, Léger et nerveux–Rubato–1er Mouvt–Con fuoco ed appassionato–Lento. -

Ariadne Auf Naxos Page 1 of 2 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 2002-2003 Ariadne auf Naxos Page 1 of 2 Opera Assn. Opera House Ariadne auf Naxos (in German) Opera in two acts by Richard Strauss Libretto by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Conductor CAST Jun Märkl The Music Teacher Theodore Baerg Production The Major-domo Frank Hoffmann John Cox A lackey Brad Alexander Designer An officer Brian Anderson Robert Perdziola The Composer Claudia Mahnke Lighting Designer The Tenor (Bacchus) Thomas Moser Duane Schuler A Wigmaker Hugh Russell Musical Preparation Zerbinetta Laura Claycomb* John Churchwell The Prima Donna (Ariadne) Deborah Voigt Carol Isaac The Ballet Master Jonathan Green Philip Kuttner Naiade Saundra DeAthos John Parr Joyce Fieldsend Dryade Jane Gilbert Peter Grunberg Echo Kristin Clayton Prompter Arlecchino Daniel Belcher Jonathan Khuner Truffaldino John Ames Supertitles Scaramuccio Kevin Conners Philip Kuttner Brighella Greg Fedderly Assistant Stage Director Kathleen Smith Sam Helfrich *Role debut †U.S. opera debut Stage Manager PLACE AND TIME: Late 17th-century Vienna Barbara Donner Monday, September 9 2002, at 8:00 PM PROLOGUE: A small private theater attached to the palace of a major sponsor Thursday, September 12 2002, at 7:30 PM THE OPERA: On the Greek island of Naxos Saturday, September 14 2002, at 8:00 PM Saturday, September 21 2002, at 8:00 PM Thursday, September 26 2002, at 8:00 PM Sunday, September 29 2002, at 2:00 PM San Francisco War Memorial 2002-2003 Ariadne auf Naxos Page 2 of 2 Opera Assn. Opera House Sponsors: The performance of September 12th is sponsored by San Francisco Opera Guild/East Bay Chapter Notes: Production owned by the Lyric Opera of Chicago made possible, in part, by a generous gift from an anonymous donor. -

TORSTAISARJA 4 Hannu Lintu, Kapellimestari Karita Mattila

20.12. TORSTAISARJA 4 Musiikkitalo klo 17.00 Hannu Lintu, kapellimestari Karita Mattila, sopraano Anssi Karttunen, sello Kari Kriikku, klarinetti Claude Debussy: Faunin iltapäivä 10 min Yuki Koyama, huilu Magnus Lindberg: Sellokonsertto nro 2, 25 min ensiesitys Suomessa I-II-III Jean Sibelius: Luonnotar op. 70 9 min VÄLIAIKA 20 min Jouni Kaipainen: Nyo ze honmak kukyo to op. 59b 6 min Kaija Saariaho: Mirage 12 min Maurice Ravel: Daphnis & Chloe, sarja nro 2 16 min I Lever du jour (Päivänkoitto) II Pantomime (Pantomiimi) III Danse générale Konsertissa soittaa Sibelius-Akatemian ja RSO:n koulutusyhteistyön myötä viisi Sibelius-Akatemian opiskelijaa: Johannes Hakulinen, 1-viulu, Khoa-Nam Nguyen, 2-viulu, Aino Räsänen, alttoviulu, Sara Viluksela, sello ja Joel Raiskio, kontrabasso. Väliaika noin klo 18.00. Konsertti päättyy noin klo 19.25. 1 JOUNI KAIPAINEN IN MEMORIAM Säveltäjä Jouni Kaipainen menehtyi pit- ja yhteistyökumppania, ikään kuin ohjel- käaikaiseen sairauteen 23. marraskuu- mistosuunnittelun jumalatar olisi tarkoi- ta. Olemme ennenaikaisesti kadottaneet tuksellisen kaukonäköisesti suunnitellut ystävän ja suuren säveltäjän, ja siksi hä- tämän kokoontumisen. Jopa Jounin hauta- nen tuotantonsa on meille entistäkin jaiset ajoittuvat näiden konserttien väliin. rakkaampi. Jounin teokset kunnioittavat Jounin suhde Radion sinfoniaorkesteriin syvästi traditiota mutta julistavat silti oli kiinteä. RSO on kantaesittänyt mm. vahvasti omalla äänellään. Yksikään län- 2. ja 4. sinfonian sekä piano- ja viulukon- simaisen kulttuurikaanonin teos tai hen- serton. Viides sinfonia oli tilattu ja viimei- kilö ei ollut hänelle vieras; kuuluihan hän nen keskusteluni Jounin kanssa koski tuon siihen itsekin. Hänen sävellystapansa to- teoksen dramaturgiaa. Lisäksi hän kirjoit- disti ainutlaatuisesta sisäisestä korvasta: ti meille satoja ohjelmakommentteja joi- teokset olivat valmiita hänen päässään or- den laaja-alainen sivistyneisyys ja teos- kestraatiota myöten, vasta sitten hän alkoi ten ymmärrys ovat vertaansa vailla. -

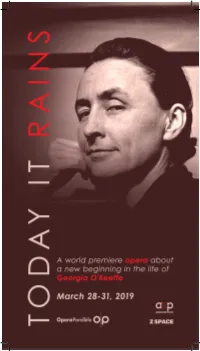

TIR-Program Compressed.Pdf

NOTE FROM NICOLE Dear Friends, This world premiere of Today It Rains marks a true milestone for Opera Parallèle, our first full scale commissioned work. This production embodies the spirit in which OP was founded, to work in ‘parallel’ with great artists and our community. Collaboration is at the heart of what we do and I believe that a positive collaborative experience can elevate a production to a whole new level. Working with Laura, Mark, Kimberly, and the rest of the creative team over the last three years has been a truly wonderful experience—I’m sure you will see this translated onto the stage. I have been humbled by the opportunity to bring the story of Georgia O’Keeffe to the operatic stage. Discovering just how influential and groundbreaking she was as an artist and as a woman has heightened my awareness of the privilege of being a female artistic leader. In particular I’m so pleased we are able to create this work with a brilliant female composer and many female creatives. This trailblazing spirit also inspired OP to celebrate women in the Bay Area who, like O’Keeffe, are breaking the mold, defying expectations, and pushing the boundaries of their field. I hope you were able to join us for the ‘Georgia & the Rebels’ event before tonight’s performance as we honor these brilliant women. Many thanks for being here, Nicole Paiement Artistic Director FROM THE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Today It Rains An Artist in Locomotion What is it about a train ride, that trance-inducing rush on rails, that can be so transformative? Anyone who has traveled on a train for any length of time knows what I am talking about. -

Houston Grand Opera Opens 2017–18 Season in the George R. Brown Convention Center with Verdi’S La Traviata (Oct

Houston Grand Opera opens 2017–18 season in the George R. Brown Convention Center with Verdi’s La traviata (Oct. 20) and Handel’s Julius Caesar (Oct. 27) Houston, October 10, 2017— Houston Grand Opera will open its 63rd season with a new production of Verdi’s most romantic opera, La traviata, October 20–November 11 in the new HGO Resilience Theater at the George R. Brown Convention Center in downtown Houston. Handel’s Julius Caesar, a Baroque opera reset in the golden age of 1930s Hollywood, opens the following week and runs October 27–November 11. HGO is transforming an exhibit hall in the convention center into an intimate theater after being displaced from its creative home at the Wortham Theater Center by Hurricane Harvey. Every seat will be less than 100 feet from the stage. The space will also give audiences insight into and connection to the theatrical process, in what the company is calling “unconventional opera.” Tickets are available at HGO.org; seating at the HGO Resilience Theater will be assigned in early October. All HGO ticket buyers to La traviata and/or Julius Caesar will receive a code for a $30 credit per ticket from Lyft to use for rides to and from the GRB ($15 per ride). Parking for HGO’s performances will be available at the Avenida North garage located at 1815 Rusk Street, across from HGO’s new venue. A sky bridge connects the parking garage to the GRB, and there will be clear signage to direct patrons to the theater. More information about parking can be found here. -

Curriculum Vitae

8008 Bluebonnet Boulevard, Apt. 18-05 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70810 Andre Chiang, baritone 251.786.1880 [email protected] Curriculum Vitae www.andrechiangbaritone.com EDUCATION Doctor of Musical Arts in Vocal Performance with a Minor in Arts Administration Louisiana State University (Baton Rouge, LA) August 2017 – May 2020 (anticipated graduation) Additional completed course work for a Minor in Vocal Pedagogy Final Project: Lecture Recital and Written Document entitled “A Performance Guide to Kurt Erickson’s Song Cycle Here, Bullet” 4.0 Grade Point Average Master of Music in Vocal Performance Manhattan School of Music (New York, NY) August 2008 – May 2010 3.942 Grade Point Average Bachelor of Music in Vocal Performance with a Minor in General Business University of South Alabama (Mobile, AL) August 2006 – May 2008 Summa Cum Laude 3.95 Grade Point Average Bachelor of Science in Accounting and Bachelor of Music in Vocal Performance (started) University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL) August 2003 – May 2006 3.976 Grade Point Average ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT and TEACHING Doctoral Teaching Assistant at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, LA Fall 2017 to Spring 2020 • Teach MUS 2130 and MUS 3130: Applied Voice Lessons, which involved assigning repertoire, weekly lessons, developing vocal technique in varying genres, informing lyric diction and preparing for jury evaluations, student sharing (splitting lesson time with a major professor at a half hour each), and student mentoring (bimonthly lessons at a half hour a piece); taught between -

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-Ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017

Compact Discs / DVD-Blu-ray Recent Releases - Spring 2017 Compact Discs 2L Records Under The Wing of The Rock. 4 sound discs $24.98 2L Records ©2016 2L 119 SACD 7041888520924 Music by Sally Beamish, Benjamin Britten, Henning Kraggerud, Arne Nordheim, and Olav Anton Thommessen. With Soon-Mi Chung, Henning Kraggerud, and Oslo Camerata. Hybrid SACD. http://www.tfront.com/p-399168-under-the-wing-of-the-rock.aspx 4tay Records Hoover, Katherine, Requiem For The Innocent. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4048 681585404829 Katherine Hoover: The Last Invocation -- Echo -- Prayer In Time of War -- Peace Is The Way -- Paul Davies: Ave Maria -- David Lipten: A Widow’s Song -- How To -- Katherine Hoover: Requiem For The Innocent. Performed by the New York Virtuoso Singers. http://www.tfront.com/p-415481-requiem-for-the-innocent.aspx Rozow, Shie, Musical Fantasy. 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4047 2 681585404720 Contents: Fantasia Appassionata -- Expedition -- Fantasy in Flight -- Destination Unknown -- Journey -- Uncharted Territory -- Esme’s Moon -- Old Friends -- Ananke. With Robert Thies, piano; The Lyris Quartet; Luke Maurer, viola; Brian O’Connor, French horn. http://www.tfront.com/p-410070-musical-fantasy.aspx Zaimont, Judith Lang, Pure, Cool (Water) : Symphony No. 4; Piano Trio No. 1 (Russian Summer). 1 sound disc $17.98 4tay Records ©2016 4TAY 4003 2 888295336697 With the Janacek Philharmonic Orchestra; Peter Winograd, violin; Peter Wyrick, cello; Joanne Polk, piano. http://www.tfront.com/p-398594-pure-cool-water-symphony-no-4-piano-trio-no-1-russian-summer.aspx Aca Records Trios For Viola d'Amore and Flute.