Introducing Rare Books Into the Undergraduate Curriculum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Dissertation Workshop Finding Primary Source Material in Special

History Dissertation Workshop Finding primary source material in Special Collections General Up-to-date information about the Special Collections Department (collection descriptions, manuscripts search, opening hours, exhibitions pages, etc) is at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/ You can navigate to the Special Collections homepage by selecting the Special Collections button at the foot of the library’s homepage. Useful resources on the Special Collections web pages Collection descriptions Each of the collections is described fully along with guidance about how to find material (including links to relevant catalogue records) at: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/collectionsa-z/ Browsing through these descriptions can help give you a ‘feel’ for the kind of material available in Special Collections, but use the subject index (follow link on left toolbar ‘Search by subject’) to ascertain which of the collections might be of most relevance to more specific topics: http://www.gla.ac.uk/services/specialcollections/searchbysubject/ Collections that might be of particular interest for pre-modern history dissertations: • Chapbooks : recreational reading of the poor in 18th & 19th Centuries • Ferguson : includes substantial collection of witchcraft literature • Hunterian : wide ranging 18th century library (early books/medieval manuscripts) • J.S.C. : pamphlets, broadsides & books from 1690-99 • Murray : collection strong in west of Scotland regional history • Ogilvie : English civil war pamphlets • Smith (ephemera) -

Benefits of the Library Treasures Volume Considered

Making treasures pay? Benefits of the library treasures volume considered K. E. Attar Senate House Library University of London [email protected] The past decade has seen the publication of numerous treasures books relating to the holdings of libraries of various sizes across several sec- tors, with more in progress at the time of writing. These glossy tomes are not cheap to produce. Apart from up-front payment of publication costs, to be recouped through sales, there is the cost of photography and staff time: selecting items to be featured, identifying and liaising with contribu- tors, writing, editing and proof-reading. Why do it? Are we on a bandwagon, keeping pace with each other because the time has come when not to have produced a treasures volume may suggest a library’s paucity of rare, valuable or significant items? If the aim is to stake a claim about status and holdings, how meaningful will treasures volumes be when we all have them? How much do they really demonstrate now, when in a sense they are a leveller: if a treasures volume features, say, one hundred items, a library with 101 appro- priate candidates can produce one just as well as a library with ten thousand items from which to choose. While only time will test the long-term value of the treasures volume in raising a library’s profile, creating such a book can be a positive enterprise in numerous other ways. This article is based on the treasures volume produced by Senate House Library, University of London, in November 2012.1 It reflects on benefits Senate House Library has enjoyed by undertaking the project, in the hope that the sharing of one library’s experience may encourage others. -

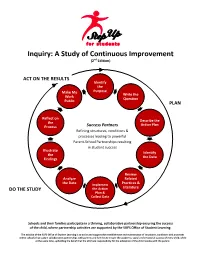

Inquiry: a Study of Continuous Improvement (2Nd Edition)

Inquiry: A Study of Continuous Improvement (2nd Edition) ACT ON THE RESULTS Identify the Make My Purpose Write the Work Question Public PLAN Reflect on Describe the the Action Plan Process Success Partners Refining structures, conditions & processes leading to powerful Parent-School Partnerships resulting in student success Illustrate Identify the the Data Findings Review Analyze Related the Data Implement Practices & Literature DO THE STUDY the Action Plan & Collect Data Schools and their families participate in a thriving, collaborative partnership ensuring the success of the child, where partnership activities are supported by the SUFS Office of Student Learning. The mission of the SUFS Office of Student Learning is to assist and support the establishment and maintenance of structures, conditions and processes within schools that sustain collaborative partnerships with parents and families to ensure the academic, social and emotional success of every child; while at the same time, upholding the belief that the ultimate responsibility for the education of the child resides with the parent. Table of Contents Welcome from Dr. Carol Thomas 1 What is Inquiry? 3 Identify the Purpose PLAN 8 Write and Refine the Question(s) PLAN 9 Describe the Action Plan PLAN 10 Identify the Data PLAN 11 Review Related Practices and Literature PLAN 13 Implement the Action Plan and Collect Data DO THE STUDY 14 Analyze the Data DO THE STUDY 15 Illustrate the Findings DO THE STUDY 16 Reflect on the Process ACT ON THE RESULTS 17 Preparing to Make My Work Public -

Book of the Month 1

ADL’s Book of the Month 1 Book of the Month Presented by ADL’s Education Department About the Book of the Month: This collection of featured books is from Books Matter: The Best Kid Lit on Bias, Diversity and Social Justice. The books teach about bias and prejudice, promote respect for diversity, encourage social action and reinforce themes addressed in education programs of A World of Difference® Institute, ADL's international anti-bias education and diversity training provider. For educators, adult family members and other caregivers of children, reading the books listed on this site with your children and incorporating them into instruction are excellent ways to talk about these important concepts at home and in the classroom. The Undefeated Kwame Alexander (Author), Kadir Nelson (Illustrator) This poetic picture book is a love letter to Black life and people in the United States. It highlights the unspeakable trauma of slavery, the faith and fire of the civil rights movement, and the passion, and perseverance of some of the world's greatest heroes. The text is also peppered with references to the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and others, offering deeper insights into the accomplishments of the past, while bringing stark attention to the endurance and spirit of Black people surviving and thriving in the present. ISBN: 978-1328780966 Publisher: Versify Year Published: 2019 Age Range: 6–9 Book Themes Black History, History of Racism, Civil Rights, Race, Racism, Courage and Persistence Key Words Discuss and define these words with children prior to reading the book. -

000 Computer Science, Information, General Works

000 000 Computer science, information, general works SUMMARY 001–006 [Knowledge, the book, systems, computer science] 010 Bibliography 020 Library and information sciences 030 General encyclopedic works 050 General serial publications 060 General organizations and museology 070 Documentary media, educational media, news media; journalism; publishing 080 General collections 090 Manuscripts, rare books, other rare printed materials 001 Knowledge Description and critical appraisal of intellectual activity in general Including interdisciplinary works on consultants Class here discussion of ideas from many fields; interdisciplinary approach to knowledge Class epistemology in 121. Class a compilation of knowledge in a specific form with the form, e.g., encyclopedias 030 For consultants or use of consultants in a specific subject, see the subject, e.g., library consultants 023, engineering consultants 620, use of consultants in management 658.4 See Manual at 500 vs. 001 .01 Theory of knowledge Do not use for philosophy of knowledge, philosophical works on theory of knowledge; class in 121 .1 Intellectual life Nature and value For scholarship and learning, see 001.2 See also 900 for broad description of intellectual situation and condition 217 001 Dewey Decimal Classification 001 .2 Scholarship and learning Intellectual activity directed toward increase of knowledge Class methods of study and teaching in 371.3. Class a specific branch of scholarship and learning with the branch, e.g., scholarship in the humanities 001.3, in history 900 For research, -

Informe Sobre La Lectura En España Por José Antonio Millán

1 LA LECTURA EN ESPAÑA 2 LA LECTURA EN ESPAÑA La lectura en España. Informe 2017 José Antonio Millán (coordinador) 3 LA LECTURA EN ESPAÑA 4 LA LECTURA EN ESPAÑA La lectura en España. Informe 2017 José Antonio Millán (coordinador) 5 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional Resumen: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Licencia: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/legalcode Usted es libre de: • Compartir: copiar y redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato. • Adaptar: mezclar, transformar, y generar una obra derivada de este material. El licenciante no puede revocar estas libertades si usted sigue los términos de la licencia. Bajo las condiciones siguientes: • Atribución. Debe citar los créditos de la obra, proporcionar un enlace a su licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios. Debe hacerlo de cualquier manera razonable, pero no de modo que sugiera que usted, o el uso que hace de la obra, tienen el apoyo del licenciante. • No comercial. No puede utilizar esta obra para fines comerciales. • Compartir bajo la misma licencia. Si mezcla o transforma esta obra, o genera una obra derivada, sólo puede distribuir la obra generada bajo la misma licencia que el original. Sin restricciones adicionales. No puede aplicar términos legales o medidas tecnológicas que impidan legalmente que otros hagan algo que la licencia permite. Preparación del original, corrección de pruebas y elaboración de los índices, Celia Villar © Del texto, los autores, 2016 © De la edición, Federación de Gremios de Editores de España, 2016 © De las fotografías del volumen (de la serie «Lecturas cercanas»): José Antonio Millán, 2016 ISBN: 978-84-86141-61-5 Depósito legal: 38.902-2016 Impreso en España. -

Books in Pieces: Granger, History, and the Collection Michael Macovski

https://doi.org/10.26262/gramma.v21i0.6284 145 Books in Pieces: Granger, History, and the Collection Michael Macovski This article analyzes the influence of James Granger’s Biographical His- tory of England (1769), a volume that spearheaded a remarkable praxis of collecting, interleaving, and rebinding during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This praxis reflects not only radical changes in concepts of col- lecting during this period, but also three central dimensions of book his- tory. These include the era’s passion for artefactual collections; its propen- sity for annotative forms, such as marginalia and prefaces; and its burgeon- ing publication of compilatory, systematized texts—such as catalogues, al- manacs, encyclopedias, and other compendium forms. The article goes on to suggest that grangerized texts extend beyond simple, stochastic gather- ings to reveal key precepts of historiographic continuity, serialized succes- sion, ekphrastic reproduction, and synoptic collectivity. I. he general outlines of the remarkable James Granger story are, in some respects, familiar: in 1769, the provincial parson publishes his Biogra- T phical History of England—a single volume that lists many portraits but contains not a single illustration. Almost immediately, the book spearheads one of the most curious movements in eighteenth-century history—a practice in which collectors acquire many prints listed by Granger, and many additional ones as well. The praxis also encompasses a veritable maelstrom of interleav- ing—which in turn gives rise to, among other terms, the verb “to grangerize,” though this term does not emerge until 1882.1 Yet such a praxis also extends beyond the initial act of interleaving. -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids And

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 065 154 LI 003 775 TITLE Library Aids and Services Available to the Blind and Visually Handicapped. First Edition. INSTITUTION Delta Gamma Foundation, Columbus, Ohio. PUB DATE [72] NOTE 44p.; (0 References) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Blind; Braille; Childrer.; Large Type Materials; Library Materials; *Library Services; *Partially Sighted; Senior Citizens; Talking Books; *Visually Handicapped ABSTRACT The information contained in this publication will be helpful in carrying out projects to aid blind and visually handicapped children and adults of all ages. Special materials available from the Library of Congress such as: talking books, books in braille, large print books, and books in moon tkpe are described. Other sources of reading materials for the blind ard partially sighted are listed, as are the magazines for the blind and partially sighted. Also included are cookbooks, and knitting and crocheting books for the blind and partially sighted. Sources of reading aids and supplies are listed and suggestions for giving personalized help to these handicapped persons are included. ()uthor/NH) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEH REPRO. DUCE() EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN. IONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF ECIU. CATION POSITION OR POUCY. LIBRARY AIDS AND SERVICES AVAILABLE TO THE BLIND AND VISUALLY HANDICAPPEDr This book was produced and printed in be Delta -

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S

Clyde Edgerton Thomas S. Kenan III Distinguished Professor of Creative Writing PhD, MAT, BA, UNC Chapel Hill Guggenheim Fellowship Lyndhurst Prize Honorary Doctorates from UNC-Asheville and St. Andrews Presbyterian College Fellowship of Southern Writers the North Carolina Award for Literature five notable book awards from the New York Times “Mr. Edgerton’s ability to shine a clear, warm light on the dark things of life without becoming sugary makes a vivid backdrop for his tolerant humor and his alertness to the human genius for nonsense.” —The New Yorker Clyde Edgerton is the author of ten novels, a book of advice, a memoir, short stories, and essays. Three of his novels have been made into movies: Raney, Walking Across Egypt, and Killer Diller. Edgerton’s short stories and essays have been published in New York Times Magazine, Best American Short Stories, Southern Review, Oxford American, Garden & Gun and other publications. Rebecca Lee associate professor MFA, University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop BA, St. Olaf College Danuta Gleed Literary Award, 2012 National Magazine Award, for “Fialta,” 2001 Bunting Fellowship, Harvard University, 2001-2002 Michener Fellowship, Iowa Writers Workshop, 1997 Rebecca Lee is the author of Bobcat and The City Is a Rising Tide. Her stories have been published in the Atlantic Monthly and Zoetrope, and she was the winner of the National Magazine Award for Fiction “Lee writes with an unflinching eye toward for “Fialta.” Her fiction has also been read on NPR’s the darkest and saddest aspects of life, often -

The Mboi Collection of Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta

56 WacanaWacana Vol. Vol. 20 No.20 No. 1 (2019): 1 (2019) 56-92 Edwin P. Wieringa, The Mboi collection of Atma Jaya Catholic University 57 The Mboi collection of Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta Edwin P. Wieringa AbstrAct Since 2018 the private collection of Ben Mboi (1935-2015), who is best known as Governor of East Nusa Tenggara – NTT – from 1978 to 1988, has been part of the Library of Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta, where it is publicly accessible under the name of Ben Mboi Research Library. The collection totals 22,890 items; the majority of the books are written in English, Indonesian, and Dutch. After briefy introducing the life and work of Ben Mboi, this article frst discusses the phenomenon of private libraries in Indonesia, making it clear that Mboi’s collection is highly unusual. The main part of the paper explores the question as to what is specifcally “Mboian” about the library and what it tells us about his mindset. Mboi’s library functioned as a collection for a working mind and the essay focuses on his books dealing with good governance, which increasinGly occupied Mboi’s mind after he entered the world of politics. Special attention is paid to reader’s marks and annotations: Mboi read his books from a decidedly Indonesian perspective. This is particularly evident in the case of Dutch books written by Dutch academics on contemporary Dutch society, which Mboi studied intensively in order to refect upon the situation in post-Suharto Indonesia. Mboi’s own political thinking, which advocated elitism and organicist statecraft, conformed to mainstream ideological discourse in the New Order, but is still de rigueur in post-Suharto Indonesia, showing a remarkable overlap with colonial ideas about leadership in the period of Dutch high imperialism. -

Eccentrics, Cranks, Outsiders, Obsessives

eccentrics, cranks, outsiders and obsessives bernard quaritch 2021 BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 Recent lists: email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Women Hippology - The Billmyer-Conant Collection II Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC, 1 Churchill Place, London E14 5HP The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman Part III Sort code: 20-65-90 The Wandering Lens: Nineteenth-Century Travel Photography Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 Recent catalogues: VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 1443 English Books & Manuscripts 1442 The English & Anglo-French Novel 1740-1840 1441 The Billmyer–Conant Collection — Hippology Front cover image from item 12 LUCAS © Bernard Quaritch 2021 by ‘an odd man’ [AMORY, Thomas]. The Life of John Buncle, Esq; 1 containing various Observations and Reflections, made in several Parts of the World; and many extraordinary Relations … London: Printed for J. Noon … 1756. 8vo., pp. ix, [7], 511, [1]; offsetting to the title-page from the turn-ins; a good copy in contemporary calf, spine gilt in compartments, a little worn; manuscript note to title- page in shorthand. £150 First edition of the strange and rambling masterpiece of the Anglo-Irish eccentric Thomas Amory (c.1691-1788). A second volume is promised on the final page, but was not published until ten years later. John Buncle, serial husband and advocate of education for women, relates picaresque adventures which are enlivened by eight marriages and numerous impassioned asides on a variety of subjects, including monogamy, the making of gold, microscopes, and a battle between a flea and a louse. -

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35Pm-11:25Pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building

INFO 6150: History of the Book Winter 2019 Thursdays, 8:35pm-11:25pm 2107 Mona Campbell Building Instructor: Jennifer Grek Martin email: [email protected] Office: Rowe 4028 Office hours: 12:00 – 2:00pm Wednesdays, or by appt. Telephone: 902 494 2462 Note: the syllabus may be subject to minor changes before and/or throughout the term. Course Description: The History of the Book encompasses the study of book and print culture from Antiquity to the present, with emphasis on the Western world. This field is anything but stodgy; book and print history is a vibrant and fascinating discipline and this course will refract this intellectual excitement through reading and discussion of recent relevant research. Throughout the course, students will investigate shifts from orality to literacy, from writing to printing, and finally from analog to digital media. The creation, production, distribution, and reception of books, serials, and ephemera will be discussed, and aspects of humanities and scientific scholarship will be explored in relation to the development of the history of book and print culture. Course Pre-Requisites: none. Learning Objectives: ~ To introduce students to the study of book and print culture and to survey the literature and scholarship of this field. ~ To discuss and evaluate the theoretical models for the study of both print and digital culture. ~ To provide intellectual and historical context for the history of books and print culture for information managers and professionals. Learning Objectives: With successful completion of this course, students should be able to… I. Explain the processes of book creation, production, dissemination, and reception – through various media – through different cultural, social-economic, and political contexts over time.