Travels Through the Foreign Imaginary on the Plautine Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic Valentina Arena, University College London Introduction According to ancient Roman authors, the Roman Republic fell because of its moral corruption.i Corruption, corruptio in Latin, indicated in its most general connotation the damage and consequent disruption of shared values and practices, which, amongst other facets, could take the form of crimes, such as ambitus (bribery), peculatus (theft of public funds) and res repentundae (maladministration of provinces). To counteract such a state of affairs, the Romans of the late Republic enacted three main categories of anticorruption measures: first, they attempted to reform the censorship instituted in the fifth century as the supervisory body of public morality (cura morum); secondly, they enacted a number of preventive as well as punitive measures;ii and thirdly, they debated and, at times, implemented reforms concerning the senate, the jury courts and the popular assemblies, the proper functioning of which they thought might arrest and reverse the process of corruption and the moral and political decline of their commonwealth. Modern studies concerned with Roman anticorruption measures have traditionally focused either on a specific set of laws, such as the leges de ambitu, or on the moralistic discourse in which they are embedded. Even studies that adopt a holistic approach to this subject are premised on a distinction between the actual measures the Romans put in place to address the problem of corruption and the moral discourse in which they are embedded.iii What these works tend to share is a suspicious attitude towards Roman moralistic discourse on corruption which, they posit, obfuscates the issue at stake and has acted as a hindrance to the eradication of this phenomenon.iv Roman analysis of its moral decline was not only the song of the traditional laudator temporis acti, but rather, I claim, included, alongside traditional literary topoi, also themes of central preoccupation to Classical political thought. -

Journal of Roman Archaeology

JOURNAL OF ROMAN ARCHAEOLOGY VOLUME 26 2013 * * REVIEW ARTICLES AND LONG REVIEWS AND BOOKS RECEIVED AN INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL Table of contents of fascicule 2 Reviews V. Kozlovskaya Pontic Studies 101 473 G. Bradley An unexpected and original approach to early Rome 478 V. Jolivet Villas? Romaines? Républicaines? 482 M. Lawall Towards a new social and economic history of the Hellenistic world 488 S. L. Dyson Questions about influence on Roman urbanism in the Middle Republic 498 R. Ling Hellenistic paintings in Italy and Sicily 500 L. A. Mazurek Reconsidering the role of Egyptianizing material culture 503 in Hellenistic and Roman Greece S. G. Bernard Politics and public construction in Republican Rome 513 D. Booms A group of villas around Tivoli, with questions about otium 519 and Republican construction techniques C. J. Smith The Latium of Athanasius Kircher 525 M. A. Tomei Note su Palatium di Filippo Coarelli 526 F. Sear A new monograph on the Theatre of Pompey 539 E. M. Steinby Necropoli vaticane — revisioni e novità 543 J. E. Packer The Atlante: Roma antica revealed 553 E. Papi Roma magna taberna: economia della produzione e distribuzione nell’Urbe 561 C. F. Noreña The socio-spatial embeddedness of Roman law 565 D. Nonnis & C. Pavolini Epigrafi in contesto: il caso di Ostia 575 C. Pavolini Porto e il suo territorio 589 S. J. R. Ellis The shops and workshops of Herculaneum 601 A. Wallace-Hadrill Trying to define and identify the Roman “middle classes” 605 T. A. J. McGinn Sorting out prostitution in Pompeii: the material remains, 610 terminology and the legal sources Y. -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

NAEVIUS After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 Was the Second

CHAPTER THREE NAEVIUS Dispositio. The Clash of Myth and History Double Identity: Campanian and Roman After Livius Andronicus, Naevius1 was the second Latin epic poet. He was of "Campanian" origin (Gellius 1. 20. 14), which, according to Latin usage, means that he was from Capua,2 a city allegedly founded by Romulus, and his thoughts and feelings were those of a Roman, not without a large admixture of Campanian pride. Capua in his day was almost as important economically as Rome and Carthage and its citizens were fully aware of this (though it was not until the Second Punic War that it abandoned Rome). Naevius himself tells us (Varro apud Gell. 17. 21. 45) that he actively participated in the First Punic War. The experience of that great historical conflict led to the birth of the Bellum Poenicum, the first Roman national epic. Similarly, Ennius would write his Annales after the Second Punic War and Virgil his Aeneid after the Civil Wars. In 235 B.C., only five years after the first performance of a Latin play by Livius Andronicus, Naevius staged a drama of his own. Soon he became the greatest comic playwright, unsurpassed until Plautus. He did not restrain his sharp tongue even when speaking of the noblest families. Although he did not mention anyone by name, he unequivocally alluded to a rather unheroic moment in the life of the young Scipio (Com. 108-110 R), and his quarrel with the Metelli (ps. Ascon., Ad Cic. Verr. 1. 29), formerly dismissed as fiction,3 is accepted today as having some basis in fact. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

'03 7V PLAUTUS. VOLUMK I. AMPHITRYON. THE COMEDY OF ASSES. THE POT OF GOLD. THE TWO BACCHISES. THE CAPTIVES. Volume II. CASIXA. THE CASKET COMEDY. CURCULIO. EPIDICUS. THE TWO MENAECHMUSES. THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY EDITED BY E. CAPPS, PH.])., LL.J1. T. E. PAGE, litt.d. ^V. H. D. ROUSE, LiTT.D. PLAUTUS III "TTTu^^TTr^cJcuTr P L A U T U S LVvOK-..f-J WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON PROFESSOR OF LATIN, BOWDOIS COLLEGE, UAINE IN FIVE VOLUMES III THE MERCHANT THE BRAGGART WARRIOR THE HAUNTED HOUSE THE PERSIAN LONDON : WILLIAM HEINEMANN NEW YORK : G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS MCMXXIV Printed in Great Britain THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE THIRD VOLUME The Mercator is an adaptation of Philemon's Emporos}- When the Emporos was produced^ how- ever, is unknown, as is the date of production of the Mercator, and of the Mosldlaria and Perm, as well. The Alason, the Greek original of the Milex Gloriosus, was very likely written in 287 B.C., the argument ^ for that date being based on interna- tional relations during the reign of Seleucus,^ for whom Pyrgopolynices was recruiting soldiers at Ephesus. And Periplectomenus's allusion to the imprisonment of Naevius* might seem to suggest that Plautus composed the Miles about 206 b.c. Philemon's Fhasma was probably the original of the Mostellaria, and written, as it apparently was, after the death of Alexander the Great and Aga- thocles,^ we may assume that Philemon presented the Phasma between 288 b.c. and the year of the death of Diphilus,^ who was living when it was produced. -

The Hebrew Bible – Like Every Story, Whether It Is Considered Fiction, Reality Or Something In-Between – Has Protagonists

LOST/LASTING IN TRANSLATION:WHAT HAPPENED TO THE LAUGHING ISAAC (GENESIS 17-26) KAROLIEN VERMEULEN The Hebrew Bible – like every story, whether it is considered fiction, reality or something in-between – has protagonists. These leading figures bear names like “Adam” and “Eve”, “Cain” and “Abel”, “David” and “Jonathan”. In most languages these names sound almost the same as in Hebrew, except for some minor phonetic changes. However, a long tradition of Bible translations, with proper nouns as the unchanging constant in an always-evolving process, tends to make us forget about the role of the name in the original text. More than a way to denote a specific person in the story, names are linked to other words: their sound and visual form, and even their meaning, are played upon. Sometimes very explicit, it is often a rather subtle second voice.1 These name-games are not specific to the Bible, but constitute a broader device widespread and loved in the ancient Near Eastern world and in antiquity in general, and one can find similar examples in Akkadian, Egyptian, and Sumerian literature, as well as 1 On name games in the Bible, their characteristics and functions, see Ian Eybers, “The Use of Proper Names as a Stylistic Device”, Semitics, 2 (1971-72); Johannes Fichtner, “Die Etymologische Ätiologie in den Namengebungen der Geschichtlichen Bücher des Alten Testaments”, Vetus Testamentum, VI/4 (1956), 372-96; Moshe Garsiel, Biblical Names: A Literary Study of Midrashic Derivations and Puns, Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1991; Robert Alter, The Art of Biblical Narrative, New York: Basic Books, 1981; Richard S. -

The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome

CHARM 2015 Proceedings Marketing an Urban Identity: The Shops and Shopkeepers of Ancient Rome 135 Rhodora G. Vennarucci Lecturer of Classics, Department of World Languages, Literatures, and Cultures, University of Arkansas, U.S.A. Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the development of fixed-point retailing in the city of ancient Rome between the 2nd c BCE and the 2nd/3rd c CE. Changes in the socio-economic environment during the 2nd c BCE caused the structure of Rome’s urban retail system to shift from one chiefly reliant on temporary markets and fairs to one typified by permanent shops. As shops came to dominate the architectural experience of Rome’s streetscapes, shopkeepers took advantage of the increased visibility by focusing their marketing strategies on their shop designs. Through this process, the shopkeeper and his shop actively contributed to urban placemaking and the distribution of an urban identity at Rome. Design/methodology/approach – This paper employs an interdisciplinary approach in its analysis, combining textual, archaeological, and art historical materials with comparative history and modern marketing theory. Research limitation/implications – Retailing in ancient Rome remains a neglected area of study on account of the traditional view among economic historians that the retail trades of pre-industrial societies were primitive and unsophisticated. This paper challenges traditional models of marketing history by establishing the shop as both the dominant method of urban distribution and the chief means for advertising at Rome. Keywords – Ancient Rome, Ostia, Shop Design, Advertising, Retail Change, Urban Identity Paper Type – Research Paper Introduction The permanent Roman shop was a locus for both commercial and social exchanges, and the shopkeeper acted as the mediator of these exchanges. -

![Law and Economy in Classical Athens: [Demosthenes], “Against Dionysodorus”](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1594/law-and-economy-in-classical-athens-demosthenes-against-dionysodorus-841594.webp)

Law and Economy in Classical Athens: [Demosthenes], “Against Dionysodorus”

is is a version of an electronic document, part of the series, Dēmos: Clas- sical Athenian Democracy, a publicationpublication ofof e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org]. e electronic version of this article off ers contextual information intended to make the study of Athenian democracy more accessible to a wide audience. Please visit the site at http:// www.stoa.org/projects/demos/home. Law and Economy in Classical Athens: [Demosthenes], “Against Dionysodorus” S is article was originally written for the online discus- sion series “Athenian Law in its Democratic Context,” organized by Adriaan Lanni and sponsored by Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies. (Suggested Read- ing: Demosthenes , “Against Dionysodorus.”) Sometime around a man named Dareius brought a private action in an Athenian court against a merchant called Dionysodorus. Dareius and his business partner Pamphilus had made a loan to Dionysodorus and his part- ner Parmeniscus for a trading voyage to Egypt and back. In his opening words of his speech to the court, Dareius describes the risks confronting men who made maritime loans. Edward M. Harris, “Law and Economy in Classical Athens: [Demosthenes] ‘Against Dionysodorus,’” in A. Lanni, ed., “Athenian Law in its Democratic Context” (Center for Hellenic Studies On-Line Discussion Series). Republished with permission in C. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy (A.(A. MahoneyMahoney andand R.R. Scaife,Scaife, edd.,edd., e Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities [www.stoa.org], . © , E.M. Harris. “We who decide to engage in maritime trade and to en- trust our property to other men are clearly aware of this fact: the borrower has an advantage over us in every re- spect. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

^-< THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY I FOUKDED BY JAMES IXtEB, liL.D. EDITED BY G. P. GOOLD, PH.D. FORMEB EDITOBS t T. E. PAGE, C.H., LiTT.D. t E. CAPPS, ph.d., ii.D. t W. H. D. ROUSE, LITT.D. t L. A. POST, l.h.d. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., f.b.hist.soc. PLAUTUS IV 260 P L A U T U S WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON DKAK OF BOWDODf COLUDOB, MAin IN FIVE VOLUMES IV THE LITTLE CARTHAGINIAN PSEUDOLUS THE ROPE T^r CAMBRIDOE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD MCMLXXX American ISBN 0-674-99286-5 British ISBN 434 99260 7 First printed 1932 Reprinted 1951, 1959, 1965, 1980 v'Xn^ V Wbb Printed in Great Britain by Fletcher d- Son Ltd, Norwich CONTENTS I. Poenulus, or The Little Carthaginian page 1 II. Pseudolus 144 III. Rudens, or The Rope 287 Index 437 THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE FOURTH VOLUME In the Prologue^ of the Poenulus we are told that the Greek name of the comedy was Kapx^Sdvios, but who its author was—perhaps Menander—or who the author of the play which was combined with the Kap;^8ovios to make the Poenulus is quite uncertain. The time of the presentation of the Poenulus at ^ Rome is also imcertain : Hueffner believes that the capture of Sparta ' was a purely Plautine reference to the war with Nabis in 195 b.c. and that the Poenulus appeared in 194 or 193 b.c. The date, however, of the Roman presentation of the Pseudolus is definitely established by the didascalia as 191 b.c. -

Near-Miss Incest in Plautus' Comedies

“I went in a lover and came out a brother?” Near-Miss Incest in Plautus’ Comedies Although near-miss incest and quasi-incestuous woman-sharing occur in eight of Plautus’ plays, few scholars treat these themes (Archibald, Franko, Keyes, Slater). Plautus is rarely rec- ognized as engaging serious issues because of his bawdy humor, rapid-fire dialogue, and slap- stick but he does explore—with humor—social hypocrisies, slave torture (McCarthy, Parker, Stewart), and other discomfiting subjects, including potential social breakdown via near-miss incest. Consummated incest in antiquity was considered the purview of barbarians or tyrants (McCabe, 25), and was a common charge against political enemies (e.g. Cimon, Alcibiades, Clo- dius Pulcher). In Greek tragedy, incest causes lasting catastrophe (Archibald, 56). Greece fa- vored endogamy, and homopatric siblings could marry (Cohen, 225-27; Dziatzko; Harrison; Keyes; Stärk), but Romans practiced exogamy (Shaw & Saller), prohibiting half-sibling marriage (Slater, 198). Roman revulsion against incestuous relationships allows Plautus to exploit the threat of incest as a means of increasing dramatic tension and exploring the degeneration of the societies he depicts. Menander provides a prototype. In Perikeiromene, Moschion lusts after a hetaera he does not know is his sister, and in Georgos, an old man seeks to marry a girl who is probably his daughter. In both plays, the recognition of the girl’s paternity prevents incest and allows her to marry the young man with whom she has already had sexual relations. In Plautus’ Curculio a soldier pursues a meretrix who is actually his sister; in Epidicus a girl is purchased as a concu- bine by her half-brother; in Poenulus a foreign father (Blume) searches for his daughters— meretrices—by hiring prostitutes and having sex with them (Franko) while enquiring if they are his daughters; and in Rudens where an old man lusts after a girl who will turn out to be his daughter. -

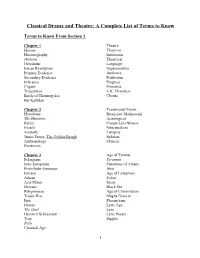

A Complete List of Terms to Know

Classical Drama and Theatre: A Complete List of Terms to Know Terms to Know From Section 1: Chapter 1 Theatre History Theatron Historiography Institution Historia Theatrical Herodotus Language Ionian Revolution Impersonation Primary Evidence Audience Secondary Evidence Positivism Inference Progress Cogent Primitive Tripartition E.K. Chambers Battle of Thermopylae Chorus Ibn Kahldun Chapter 2 Transitional Forms Herodotus Bronislaw Malinowski The Histories Aetiological Relics Claude Levi-Strauss Fossils Structuralism Aristotle Lumpers James Frazer, The Golden Bough Splitters Anthropology Mimetic Positivism Chapter 3 Age of Tyrants Pelasgians Tyrannos Indo-Europeans Pisistratus of Athens Proto-Indo-European Attic Ionians Age of Lawgivers Athens Solon Asia Minor Sicily Dorians Black Sea Peloponnese Age of Colonization Trojan War Magna Graecia Epic Phoenicians Homer Lyric Age The Iliad Lyre Heinrich Schliemann Lyric Poetry Troy Sappho Polis Classical Age 1 Chapter 4.1 City Dionysia Thespis Ecstasy Tragoidia "Nothing To Do With Dionysus" Aristotle Year-Spirit The Poetics William Ridgeway Dithyramb Tomb-Theory Bacchylides Hero-Cult Theory Trialogue Gerald Else Dionysus Chapter 4.2 Niches Paleontologists Fitness Charles Darwin Nautilus/Nautiloids Transitional Forms Cultural Darwinism Gradualism Pisistratus Steven Jay Gould City Dionysia Punctuated Equilibrium Annual Trading Season Terms to Know From Section 2: Chapter 5 Sparta Pisistratus Peloponnesian War Athens Post-Classical Age Classical Age Macedon(ia) Persian Wars Barbarian Pericles Philip -

Amphitryon from Plautus to Gib.Audoux Lia

.AMPHITRYON FROM PLAUTUS TO GIB.AUDOUX LIA STAICOPOULOU '• Master of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stilhrater, Oklahoma 1951 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Mey, 1953 ii fflO~!OMA AGRICDLTURAL & t:![C;; ,idCAl OOUEGI LL~RAR Y DEC 10 1953 AMPHITRYON FROM Pl,AUTUS TO GmAUDOUX 'l'hesis Approved: &£ .. c~ De Em of the Graduate School 309068 iii The writer wishes to e:;cpi-ess her appreciation to Professor A. A. Arnold., Professor Richard E. Bailey, Pro.f'e.ssor M. H. Griffin, and Professor Anna Oursler for their mro1:;r kindnesses during this and past semeotero. Professor Bmley, um:1er whose su,pervision this pa.per was witten, has been the source of' rmch veJ.uable advice and guidance. His patience ari..d helpfulness are deeply a.ppreeie:ted. P-i."'ofessor Griffin read the paper critically and offered mai:zy- useful sr:ggestions. A11 expression of gratitude is cl.so extended to the enti:r;'.l Oklahome, A. ~tnd M. College libr&TIJ sttd'f, especial~ to Mr. Alton P. Julllin i'or his d<l in obttlning rere books, and to I-'Irs. Marguerite Jfowle1-:i.d for nclcing ·i:;he facili:hies or her department so rea.dily available. Specicl :mention should also be made of Mrs. Jan Duker for proofreading the paper and of Mr. Go1... don Culver i'or his competence e.nd promptness i11 typing it. iv TABLE OF CONT s Chapter I.