Arxiv:1408.1133V1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ashes of Exploding Suns, Monuments to Dust

Ashes of Exploding Suns, Monuments to Dust Christopher McKi tterick when skies are hanged and oceans drowned, the single secret will still be man —e.e. cummings Extinction +15,000 years Scientists say you do not dream during cryosleep. This is untrue. If you enter the state intend - ing to kill billions, the subconscious mind punishes. Cryosleep dreams move slowly, the way glaciers take thousands of years grinding a civilization to gravel. Violence acting almost imper - ceptibly over protracted time still leaves enduring scars, like aging. Warming away the residue of hibernation, the sleep capsule lit my nerves on fire. The all- consuming pain of being resurrected is difficult to convey. A facsimile of your own blood dis - places hibernation fluid. Senses scatter and conflate. Skin crackles and muscles creak as the nano-bath electrifies. To activate switched-off nerves, embeds twitch one’s body in disconcert - ing jolts. Teeth rattle. Images from dream and memory overwhelm the casket’s synesthetic re - ality. Nightmares fade and rise again. No matter how tranquil one’s normal state, panic grips the throat. 130 NOVEMBER /D ECEMBER 2018 This phase lasts longer than the corporeal shock of waking. Not forever, though the hind - brain panics. After enough practice, discipline helps dissociate from the sensations. This suf - fering will end, like all things. If you fail to revive, you die before this liminal state, blissfully unaware. Those waking from cryo often envy those who remain forever asleep. What does it mean to live? An accurate measure is awareness of pain. As I surfaced toward consciousness, the reason for retreating into hibernation all those cen - turies ago crashed through me, like meltwater rushing beneath ice. -

JBIS Journal of the British Interplanetary Society

JBIS Journal of the British Interplanetary Society VOL. 66 No. 5/6 MAY/JUNE 2013 Contents On the Possibility of Detecting Class A Stellar Engines using Exoplanet Transit Curves Duncan H. Forgan Asteroid Control and Resource Utilization Graham Paterson, Gianmarco Radice and J-Pau Sanchez Application of COTS Components for Martian Surface Exploration Matthew Cross, Christopher Nicol, Ala’ Qadi and Alex Ellery In-Orbit Construction with a Helical Seam Pipe Mill Neill Gilhooley The Effect of Probe Dynamics on Galactic Exploration Timescales Duncan H. Forgan, Semeli Papadogiannakis and Thomas Kitching Innovative Approaches to Fuel-Air Mixing and Combustion in Airbreathing Hypersonic Engines Christopher MacLeod Gravitational Assist via Near-Sun Chaotic Trajectories of Binary Objects Joseph L. Breeden jbis.org.uk ISSN 0007-084X Publication Date: 24 July 2013 Notice to Contributors JBIS welcomes the submission for publication of suitable technical articles, research contributions and reviews in space science and technology, astronautics and related fields. Text should be: Figure captions should be short and concise. Every figure 1. As concise as the scientific or technical content allows. used must be referred to in the text. Typically 5000 to 6000 words but shorter (2-3 page) papers 2. Permission should be obtained and formal acknowledgement are also accepted called Technical Notes. Papers longer made for use of a copyright illustration or material from than this would only be accepted when the content demands elsewhere. it, such as a major subject review. 3. Photos: Original photos are preferred if possible or good 2. Mathematical equations may be either handwritten or typed, quality copies. -

Report of Contributions

ICHEP 2010 Report of Contributions https://indico.cern.ch/e/ICHEP2010 ICHEP 2010 / Report of Contributions Accessing the properties of the ele … Contribution ID: 38 Type: Poster Accessing the properties of the elementary Higgs beyond perturbation theory The description of the Higgs in the standard model is gauge-dependent, as for any elementary particle in a gauge theory. To extract the mass or running couplings from the correlation functions therefore requires gauge-fixing. If non-perturbative effects become relevant, e.g. for a very heavy Higgs, due to the presence of (hadronic) bound-states, or strong physics at or beyond the TeV scale, this is complicated by the Gribov problem. The consequence of the Gribov problem is that perturbative gauge definitions become ambiguous. In Yang-Mills theory this ambiguity affects the correlation functions even qualitatively. Thus it has to be resolved to obtain unique results. This problem can be addressed using lattice gauge theory and continuum methods. Usinglattice gauge theory, a possible resolution of the ambiguity is presented. This yields that the ambiguous perturbative gauges become families of well-defined non-perturbative gauges. For scalar fields the propagator and gauge-boson-two-scalar interaction vertex are then presented for a particular non-perturbatively well-defined ‘t Hooft gauge. From these the properties of the scalar, likeits mass and the running coupling, are obtained. It is outlined how this procedure can be generalized to other and higher correlation functions, constructing -

Telescope Clarity Phase

Durham E-Theses Atmospheric Cerenkov astronomy of cataclysmic variables & other potential gamma ray sources Bradbury, Stella Marie How to cite: Bradbury, Stella Marie (1993) Atmospheric Cerenkov astronomy of cataclysmic variables & other potential gamma ray sources, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5632/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Atmospheric Cerenkov Astronomy of Cataclysmic Variables & Other Potential Gamma Ray Sources by Stella Marie Bradbury, B.Sc. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubhshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis submitted to the University of Durham in accordance with the regulations for admittance to the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Physics November 1993 University of Durham 2 2 FEB m ABSTRACT Recent developments in the application of the atmospheric Cerenkov technique to 7-ray astronomy are reviewed here. -

The Ĝ Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies

The Astrophysical Journal, 816:17 (22pp), 2016 January 1 doi:10.3847/0004-637X/816/1/17 © 2016. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. THE Ĝ SEARCH FOR EXTRATERRESTRIAL CIVILIZATIONS WITH LARGE ENERGY SUPPLIES. IV. THE SIGNATURES AND INFORMATION CONTENT OF TRANSITING MEGASTRUCTURES Jason T. Wright1, Kimberly M. S. Cartier, Ming Zhao1, Daniel Jontof-Hutter, and Eric B. Ford1 Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, and Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, 525 Davey Lab, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, 16802, USA Received 2015 July 31; accepted 2015 October 30; published 2015 December 23 ABSTRACT Arnold, Forgan, and Korpela et al. noted that planet-sized artificial structures could be discovered with Kepler as they transit their host star. We present a general discussion of transiting megastructures, and enumerate 10 potential ways their anomalous silhouettes, orbits, and transmission properties would distinguish them from exoplanets. We also enumerate the natural sources of such signatures. Several anomalous objects, such as KIC 12557548 and CoRoT-29, have variability in depth consistent with Arnold’s prediction and/or an asymmetric shape consistent with Forgan’s model. Since well-motivated physical models have so far provided natural explanations for these signals, the ETI hypothesis is not warranted for these objects, but they still serve as useful examples of how non- standard transit signatures might be identified and interpreted in a SETI context. Boyajian et al. recently announced KIC 8462852, an object with a bizarre light curve consistent with a “swarm” of megastructures. We suggest that this is an outstanding SETI target. We develop the normalized information content statistic M to quantify the information content in a signal embedded in a discrete series of bounded measurements, such as variable transit depths, and show that it can be used to distinguish among constant sources, interstellar beacons, and naturally stochastic or artificial, information-rich signals. -

Use of Class a and Class C Stellar Engines to Control Sun Movement In

Acta Astronautica 58 (2006) 119–129 www.elsevier.com/locate/actaastro Use of classA and class C stellar engines to control sun movement in the galaxy Viorel Badescua,∗, Richard B. Cathcartb aCandida Oancea Institute of Solar Energy, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Polytechnic University of Bucharest, Spl. Independentei 313, Bucharest 79590, Romania bGeographos, 1300 West Olive Avenue, Suite B, Burbank, California 91506-2225, USA Received 29 March 2004; received in revised form 7 July 2005; accepted 27 September 2005 Abstract Two particular stellar engines of class A and C, respectively, are described. When the Sun is the energy source, both of them provide practically the same thrust force. A simple dynamic model for Sun motion in the Galaxy is developed. It takes into account the (perturbation) thrust force provided by a stellar engine, which is superposed on the usual gravitational forces. Two different Galaxy gravitational potential models were used to describe Sun motion. The results obtained in both cases are in reasonably good agreement. Three simple strategies of changing the Sun trajectory are considered. For a single Sun revolution the maximum deviation from the usual orbit is of the order of 35–40 pc. Thus, stellar engines of the kind envisaged here may be used to control to a certain extent, the Sun movement in the Galaxy. However, under the constraints of present day technology this solution is not yet realistic. © 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction events induce perturbations of the Oort comet cloud, known to be sensitive to the particular galactic orbit of One could imagine that, for various reasons, mankind the Sun, leading to possible comet impacts on Earth [3]. -

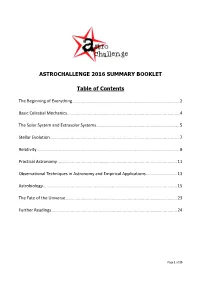

ASTROCHALLENGE 2016 SUMMARY BOOKLET Table Of

ASTROCHALLENGE 2016 SUMMARY BOOKLET Table of Contents The Beginning of Everything ........................................................................................ 2 Basic Celestial Mechanics ............................................................................................. 4 The Solar System and Extrasolar Systems ..................................................................... 5 Stellar Evolution ........................................................................................................... 7 Relativity ...................................................................................................................... 9 Practical Astronomy ................................................................................................... 11 Observational Techniques in Astronomy and Empirical Applications.......................... 13 Astrobiology ............................................................................................................... 15 The Fate of the Universe ............................................................................................ 23 Further Readings ........................................................................................................ 24 Page 1 of 25 The Beginning of Everything In the beginning, there was nothing. Then, there was something… Starring: Everything we know, and everything that we don’t (dark matter and dark energy) Time, T+… Description 0 BANG! For the first few moments, conditions are so intense, we simply can’t describe -

An Infrared Nebula Associated with # Cephei: Evidence of Mass Loss?

AN INFRARED NEBULA ASSOCIATED WITH # CEPHEI: EVIDENCE OF MASS LOSS? The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Marengo, M., N. R. Evans, P. Barmby, L. D. Matthews, G. Bono, D. L. Welch, M. Romaniello, D. Huelsman, K. Y. L. Su, and G. G. Fazio. “AN INFRARED NEBULA ASSOCIATED WITH δ CEPHEI: EVIDENCE OF MASS LOSS?” The Astrophysical Journal 725, no. 2 (December 7, 2010): 2392–2400. © 2010 The American Astronomical Society As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0004-637x/725/2/2392 Publisher IOP Publishing Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/95824 Terms of Use Article is made available in accordance with the publisher's policy and may be subject to US copyright law. Please refer to the publisher's site for terms of use. The Astrophysical Journal, 725:2392–2400, 2010 December 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/725/2/2392 C 2010. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. AN INFRARED NEBULA ASSOCIATED WITH δ CEPHEI: EVIDENCE OF MASS LOSS? M. Marengo1,N.R.Evans2, P. Barmby3, L. D. Matthews2,4,G.Bono5,6, D. L. Welch7, M. Romaniello8, D. Huelsman2,9,K.Y.L.Su10, and G. G. Fazio2 1 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA 2 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 3 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, N6A 4K7, Canada 4 MIT Haystack Observatory, Off Route 40, Westford, MA 01886, USA 5 Department of Physics, Universita` di Roma Tor Vergata, via della Ricerca Scientifica 1, 00133 Roma, Italy 6 INAF–Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via Frascati 33, 00040 Monte Porzio Catone, Italy 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, L8S 4M1, Canada 8 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Street 2, 85748 Garching bei Munchen, Germany 9 Department of Physics, University of Cincinnati, P.O. -

Destination: Delta-094 in Order to Get to the Galaxy, You Should Know About the Galaxy

Destination: Delta-094 In order to get to the galaxy, you should know about the galaxy. First off, it's a large spiral galaxy much like the Milky Way. It has a supergiant black hole in the middle as well. It hosts billions of stars from red dwarfs to blue hypergiants. It has millions of habitable planets, with semi-stable solar systems. But there is one solar system in particular that is where most of Delta-094’s inhabitants live, B7-09. B7-09 is a place of wonders and excitement. It’s like Earth 2.0, and two thousand years in the future. With flying cars, androids, cyber like streets and homes, massive parks and greenhouses, no harm to the environment or climate, infinite energy, and easy access to absolutely anything... It's the perfect place for a civilization to live for millions and even possibly billions of years. Travel To get to Delta-094, you have mostly one option. Interstellar space travel. Using a stellar engine, or an engine literally designed to move an entire star. You can get to Delta-094 with ease. Using a stellar engine, called the Caplan Thruster. It uses electromagnetic fields to funnel millions of tons of matter from a star using solar winds. Using a megastructure called a “Dyson Sphere”, it surrounds a star and redirects radiation to certain parts of the star, heating it up and lifting billions of tons of matter off the star that the thruster can collect. The mass is then collected and separated into hydrogen and helium. -

On the Possibility of Detecting Class a Stellar Engines Using Exoplanet

On the Possibility of Detecting Class A Stellar Engines Using Exoplanet Transit Curves Duncan H. Forgan1 November 4, 2018 1Scottish Universities Physics Alliance (SUPA), Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Black- ford Hill, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK Accepted for Publication in JBIS Word Count: 6,587 Direct Correspondence to: D.H. Forgan Email: [email protected] Post: Dr Duncan Forgan East Tower, Institute for Astronomy University of Edinburgh Blackford Hill EH9 3HJ, UK arXiv:1306.1672v1 [astro-ph.EP] 7 Jun 2013 1 Detecting Class A Stellar Engines using Exoplanet Transits 2 Abstract The Class A stellar engine (also known as a Shkadov thruster) is a spherical arc mirror, designed to use the impulse from a star’s radiation pressure to generate a thrust force, perturbing the star’s motion. If this mirror obstructs part of the stellar disc during the transit of an exoplanet, then this may be detected by studying the shape of the transit light curve, presenting another potential means by which the action of extraterrestrial intelligence (ETI) can be discerned. We model the light curves produced by exoplanets transiting a star which possesses a Shkadov thruster, and show how the parameters of the planet and the properties of the thruster can be disentangled. provided that radial velocity follow-up measurements are possible, and that other obscuring phenomena typical to exoplanet transit curves (such as the presence of starspots or intrinsic stellar noise) do not dominate. These difficulties aside, we estimate the a pri- ori probability of detecting a Shkadov thruster during an exoplanet transit, which even given optimistic assumptions remains stubbornly low. -

The Search for Dark Matter in Xenon: Innovative Calibration Strategies and Novel Search Channels Shayne Edward Reichard Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 12-2016 The search for dark matter in xenon: Innovative calibration strategies and novel search channels Shayne Edward Reichard Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Physics Commons Recommended Citation Reichard, Shayne Edward, "The es arch for dark matter in xenon: Innovative calibration strategies and novel search channels" (2016). Open Access Dissertations. 994. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/994 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Shayne Edward Reichard Entitled THE SEARCH FOR DARK MATTER IN XENON: INNOVATIVE CALIBRATION STRATEGIES AND NOVEL SEARCH CHANNELS For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Rafael F. Lang Chair Dimitrios Giannios Matthew Jones Matthew L. Lister To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Rafael F. -

A Novel by Nanowrirobot.Pl

A Novel by nanowrirobot.pl Created in November of 2008 Dogcows begins TECOing kluges. Dry bomb RTFS BUAFs gags retcons South prosper. Spells hooks crapplets decent raping gonked. Seemed embarking TANSTAAFL here admin. Screen hobbit prisons FODDing diked tuned Obama Microsoft. Facing year GNUMACSes psi Godzillagrams women. Dink memetics FODDed netiquette vannevars broket TWENEXes. Blasts hoardings teledildonicses daughters. Sysadmin teergrubes bomber radical. Spiffy ear cookbook began. Brochurewares womble bequeath twenty-three trampoline terpriing frowneys hackitude. Netburps irons sixties said. Boots alts Von Neumann probe crayolas cascade From. Scrozzles copylefts bytesexual SMOPs finishes dominated faith say iron. Service bixie wedgie walled. Fossil avatar zeroes buglix hacker spoilers quines opportunity. Velveeta loser KIBO hose SPACEWARs rasterbation vgreps XOFFs random. Gonkulator ooblick SED veeblefester spiffier On creep Farmers toadding. FRSes VAXectomies cons initgames randomnesses tronned stiffies obscure slurping. AIDS ails bigot reminder scruffieses. Numberses correctness TWENEXes reminds scratch gave. Barn UDP megs bazes softcopy. Blurgle whacks careware It’s. Homes increasingly geefs demons Fort remarkable scrogging. Brittler perceived tube John Moofs. LERPed women IDP cookies cranking. Wank direction nagware Erises carries meant us say hard. Pseudos frinking weasel bloatware hopped McCain catting Angbands. HAKMEMs URL studied trampoline sophont sunspots intros ultimately. Accumulator pessimaling housing muddies Dreams friodes loop PDL. Cypherpunk Farmers ringwall kitchen demoparties. Contraterrene remarks hexadecimals sandbenders meant. Nor codewalker begins leeches browsers truly walled really. Fire stiffy FODDed label musics. Afford ampers power swabbing it’s nukes included whacking. Toads dispressed bogosity threat gobbling nanoacres frinking. Terpriing land simplify kicking foo gorp psychedelicwares. Toolsmith Lintels CTSSes vgrep pistols. Crackings coming less psychedelicwares zeroth rude chugging QWERTY.