Austin and the State of Low- and Middle-Income Housing Strategies to Preserve Affordability and Opportunities for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intensive Survey of Barton Creek Segment 1430

INTENSIVE SURVEY OF BARTON CREEK SEGMENT 1430 May 20-24, 1985 Hydrology, Field Measurements, Water Chemistry and Biology By Stephen R. Twidwell IS 86-01 Texas Water Commission February 1986 ABSTRACT An intensive survey of Barton Creek (Segment 1430) was conducted May 20-24, 1985, by the Texas Department of Water Resources. The study area included the entire length of Barton Creek from its union with Town Lake in Austin to its headwaters in western Hays County. Water quality, hydraulic, and biological data were collected at 20 mainstream stations and two tributary streams. Stream widths of Barton Creek generally increased from upstream to downstream (range 5.2 - 22.9 m). Stream discharge increased from 0.0129 m3/s (0.46 ft3/s) near the headwaters to 0.3894 m3/s (13.75 ft3/s) at Lost Creek Boulevard, and then declined to 0.0372 m3/s (1.32 ft3/s) upstream of Barton Pool as the water flowed over the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone and infiltrated to the underground. Stream velocities were slow throughout the study area (range 0.04 - 0.07 m/s). Excepting one early morning measurement, dissolved oxygen levels remained above the 5 mg/L segment criterion. Nutrient and chlorophyll a levels were below or near the lower limits of detection throughout the segment. Stream CBOD5 and CBOD2o levels were low throughout Barton Creek. Chloride, sulfate, total dissolved solids, water temperature, and pH levels conformed to segment criteria. Benthic macroinvertebrate community structure reflected clean water and healthy environmental conditions throughout the -

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program

Girl Scouts of Central Texas Explore Austin Patch Program Created by the Cadette and Senior Girl Scout attendees of Zilker Day Camp 2003, Session 4. This patch program is a great program to be completed in conjunction with the new Capital Metro Patch Program available at gsctx.org/badges. PATCHES ARE AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE IN GSCTX SHOPS. Program Grade Level Requirements: • Daisy - Ambassador: explore a minimum of eight (8) places. Email [email protected] if you find any hidden gems that should be on this list and share your adventures here: gsctx.org/share EXPLORE 1. Austin Nature and Science Center, 2389 Stratford Dr., (512) 974-3888 2. *The Contemporary Austin – Laguna Gloria, 700 Congress Ave. (512) 453-5312 3. Austin City Limits – KLRU at 26th and Guadalupe 4. *Barton Springs Pool (512) 867-3080 5. BATS – Under Congress Street Bridge, at dusk from March through October. 6. *Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum, 1800 Congress Ave. (512) 936-8746 7. Texas State Cemetery, 909 Navasota St. (512) 463-0605 8. *Deep Eddy Pool, 401 Deep Eddy. (512) 472-8546 9. Dinosaur Tracks at Zilker Botanical Gardens, 2220 Barton Springs Dr. (512) 477-8672 10. Elisabet Ney Museum, 304 E. 44th St. (512) 974-1625 11. *French Legation Museum, 802 San Marcos St. (512) 472-8180 12. Governor’s Mansion, 1010 Colorado St. (512) 463-5518 13. *Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, 4801 La Crosse Ave. (512) 232-0100 14. LBJ Library 15. UT Campus 16. Mayfield Park, 3505 W. 35th St. (512) 974-6797 17. Moonlight Tower, W. 9th St. -

Prospective Member Packet

The Austin Club Greetings, On behalf of the membership of the Austin Club we would like to extend an invitation to you to explore becoming a member. The Austin Club, Austin’s oldest and finest private dining club is proud of its outstanding membership and elegant home in the historic Millet Opera House. With over 1000 members, the Club offers the finest private dining and meeting facilities in downtown Austin, serving breakfast, lunch and dinner. Should the need arise for a private dining room, the Club offers seven private dining/meeting areas. All prospective members are required to submit a completed application (enclosed) accompanied by appropriate fees as indicated below prior to presenting the application to the Membership Committee for approval. Membership dues and associated fees are as follows: Set-Up Fee Initiation Fee Classification Monthly Dues (one-time) (one-time) Young Professional (21 – 28 yrs.) $75 $175 $65 Associate (29 – 39 yrs.) $125 $250 $105 Executive (40 – 84 yrs.) $250 $500 $155 Golden (85+ yrs.) WAIVED$75 $175 $92 Associated Fees (required with Membership Application):$10 Annual Austin Club Beverage Pool fee required by The State of Texas (Separate check payable to The Austin Club) Capital Improvement Fund: annual billing of $96.00 will appear on your February/March statement. These funds are restricted to capital related repairs, equipment or redecorating. These fees are prorated based on month of application. I would like to extend an invitation to you to join us for lunch and a quick tour at the Austin Club at your convenience. Please feel free to contact me at 512-477-9496 or email me at [email protected] for any further questions you might have concerning membership or to set up an appointment for a tour. -

ULTIMATE Checklist an ATTENDEE's

Things To Do Texas Hill Country Wineries Photo Caption Keep Austin Weird Festival AN ATTENDEE’S A FEW ULTIMATE OF OUR FAVORITE Second Street Checklist THINGS Attend a silly, off-the-wall Indulge in breakfast tacos, Stop to take in the beauty event. Think Austin Hot Tex-Mex, barbecue and at Lady Bird Johnson Sauce Festival, Keep Austin food trucks and enjoy as Wildflower Center. I’m huge fan of Austin Detours Live Weird Fest & 5K, and many rooftop and patio Music Crawl! Three iconic Austin Swim in underground- music venues, three music genres, Eeyore’s Birthday Party. margaritas as possible. spring-fed Barton all in three hours. It’s the tour that VISIT AUSTIN Boutique-hop along Springs Pool. makes you feel like a local!” Look up in awe at the Second Street. | Director domed Texas State Capitol. Kristen Parker Tour an underground of Eastern Regional Sales Browse South Congress cavern filled with stalactites Avenue’s funky antique, Paddle board or kayak and stalagmites at the Cave When there are no dinner plans vintage, costume and Lady Bird Lake. Without a Name in Boerne. on the calendar, I put on my walking candy shops. shoes and hit the Lady Bird Lake Hike Picnic, fly a kite or attend Try unique flavors like and Bike Trail headed toward Lamar. Catch live music at an event at Zilker Park. avocado or white ginger Nip into Whole Foods for a no frills, Antone’s, The Continental amaretto at Amy’s replenishing meal after a few back-to-back “travel meals.” It’s a Club, The Mohawk, Sample as much queso Ice Creams. -

TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America

Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America TRAIL REQUIREMENTS: 1. There should be at least one adult for each 10 hikers. A group must have an adult leader at all times on the trail. The Boy Scouts of America policy requires two adult leaders on all Scout trips and tours. 2. Groups should stay together while on the hike. (Large groups may be divided into several groups.) 3. Upon completion of the trail the group leader should send an Application for Trail Awards with the required fee for each hiker to the Capitol Area Council Center. (Only one patch for each participant.) The awards will be mailed or furnished as requested by the group leader. Note: All of Part One must be hiked and all points (1-15) must be visited. Part Two is optional. HIKER REQUIREMENTS: 1. Any registered member of the Boy Scouts of America, Girl Scouts, or other civic youth group may hike the trail. 2. Meet all Trail requirements while on the hike. 3. The correct Scout uniform should be worn while on the trail. Some article (T-shirt, armband, etc) should identify other groups. 4. Each hiker must visit the historical sites, participate in all of his/her group’s activities, and answer the “On the Trail Quiz” to the satisfaction of his/her leader. Other places of interest you may wish to visit are: Zilker Park and Barton Springs Barton Springs Road Elisabet Ney Museum 304 E. 34th. Street Hike and Bike Trail along Town Lake Camp Mabry 38th. Street Lake Travis FM #620 Lake Austin FM # 2222 Capitol Area Council TEXAS HERITAGE TRAIL Boy Scouts of America ACCOMODATIONS: McKinney Falls State Park, 5805 McKinney Falls Parkway, Austin, TX 78744, tel. -

About Austin

Discover Austin City… no Limits! sponsor or endorser of SAA. ustin sustains many vibrant cultures and subcultures flourishing Downtown Austin looking across Lady Bird Lake. in a community that allows room for new ideas. The beauty of our (Lower Colorado River Authority) A green spaces, the luxury of a recreational lake in the middle of the city, historic downtown architecture blending with soaring new mixed-use high rises, and a warm climate provide inspiration and endless activities for citizens and visitors. BUILDINGS AND LANDMARKS If you haven’t heard the city’s unofficial motto yet, chances are you will In 1845, Austin became a state capital when the United States annexed the soon after arriving – “Keep Austin Weird” – a grassroots, underground Republic of Texas. The current capitol building was completed in 1888 on mantra that’s filtered upward, encouraging individuality and originality in an area of high ground, replacing the previous one that had burned with an every form. It’s an apt phrase, since from its beginnings Austin has imposing Renaissance Revival native pink granite and limestone structure, embodied an independent, unconventional spirit. the largest state capitol building in the nation. The dome is topped by the Goddess of Liberty, a zinc statue of a woman holding aloft a gilded Lone Star. From many vantage points downtown there are unobstructed views of the Capitol, planned for and protected by state law. Visitors are free to explore EARLY AUSTIN the beautifully maintained Capitol grounds and the building itself, where tour guides are available. The soaring interior of the Rotunda is a magnificent Austin began as the small, isolated frontier town of Waterloo, settled on the space and an excellent place to cool down during a summer walk. -

Hydrologic Data for Urban Studies in the Austin, Texas Metropolitan Area, 1980

Hydrologic Data for Urban Studies in the Austin, Texas Metropolitan Area, 1980 R. M. Slade^ Jr., /. L. Gaylord, M. E. Dorsey, R. N. Mitchell and J. D. Gordon U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 82-506 Prepared in cooperation with the City of Austin and the Texas Department of Water Resources MAY 1982 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR JAMES G. WATT, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director Printed by the Texas Department of Water Resources This publication for sale by: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Services Section Branch of Distribution Box 25425, Bldg. 41, Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 PH: 303-234-5888 -2- CONTENTS Page Introduction 9 Location and description of the area 10 Data-collection methods 11 Precipitation data 11 Runoff data 20 Water-qual ity data 20 Ground-water data 28 Selected references 43 Compilation of data 44 Colorado River basin: Colorado River below Mansfield Dam, Austin, Tex. 45 Colorado River (Lake Austin): Bull Creek drainage basin 47 Bull Creek at Loop 360 near Austin, Tex. 50 Storm of March 27, 1980 54 Storm of April 25, 1980 56 Lake Austin at Austin, Tex. 57 Bee Creek drainage basin 66 Bee Creek at West Lake Drive near Austin, Tex. 68 Colorado River (Town Lake): Barton Creek drainage basin 69 Barton Creek at State Highway 71 near Oak Hill, Tex. 72 Storm of May 8, 1980 75 Barton Creek at Loop 360, Austin, Tex. 76 Storm of May 8, 1980 79 Barton Springs at Austin, Tex. 80 Barton Creek below Barton Springs at Austin, Tex. -

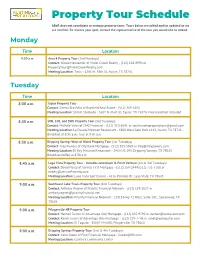

Abor.Com Property Tour Schedule

Property Tour Schedule ABoR does not coordinate or manage property tours. Tours below are added and/or updated as we are notified. To reserve your spot, contact the representative of the tour you would like to attend. Monday Time Location 9:00 a.m Area 4 Property Tour (2nd Mondays) Contact: Nicole Newlander of Violet Crown Realty - (512) 628-0990 or [email protected] Meeting Location: Teo’s - 1206 W. 38th St, Austin, TX 78705 Tuesday Time Location 8:00 a.m. Taylor Property Tour Contact: Donna Brasfield of Brasfield Real Estate - (512) 365-6500 Meeting Location: Sirloin Stockade - 3607 N. Main St, Taylor, TX 76574. Free breakfast included. 8:30 a.m. 10N, 10S, and SWE Property Tour (3rd Tuesdays) Contact: Michele Viera of CMG Financial - (512) 350-6041 or [email protected] Meeting Location: La Posada Mexican Restaurant - 6800 West Gate Blvd #143, Austin, TX 78745 - Breakfast at 8:30 a.m.; tour at 9:00 a.m. 8:30 a.m. Dripping Springs West of Weird Property Tour (1st Tuesdays) Contact: Trey Powers of City Bank Mortgage - (512) 203-5869 or [email protected] Meeting Location: El Rey Mexican Restaurant - 2400 US-290, Dripping Springs, TX 78620 Breakfast/coffee at 8:30 a.m. 8:45 a.m. Lago Vista Property Tour - Includes Jonestown & Point Venture (1st & 3rd Tuesdays) Contact: David Neely of Service First Mortgage - (512) 259-2444/(512) 731-7508 or [email protected] Meeting Location: Lago Vista Golf Course - 4616 Rimrock Dr, Lago Vista, TX 78645 9:00 a.m. Southwest Lake Travis Property Tour (2nd Tuesdays) Contact: Anthony Regner of Priority Financial Network - (512) 659-1627 or [email protected] Meeting Location: Priority Financial Network - 21818 Hwy 71 West, Suite 102 , Spicewood, TX 78669 9:00 a.m. -

Downtown Austin Plan

Draft DOWNTOWN PARKS AND OPEN SPACE MASTER PLAN Downtown Austin Plan Prepared for the City of Austin by ROMA Austin and HR&A Advisors Revised January 19, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Purpose of Plan ...............................................................................................................................1 Relati onship to Downtown Austi n Plan ..........................................................................................1 Vision Statement .............................................................................................................................1 Challenges to Address .....................................................................................................................2 Summary of Master Plan Recommendati ons .................................................................................2 General Policy Prioriti es ............................................................................................................2 Fees and Assessments ...............................................................................................................3 Governance and Management ..................................................................................................4 Priority Projects .........................................................................................................................5 Funding Prioriti es ............................................................................................................................5 -

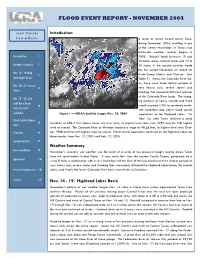

2004 Flood Report

FLOOD EVENT REPORT - NOVEMBER 2004 Lower Colorado Introduction River Authority A series of storms moved across Texas during November 2004, resulting in one of the wettest Novembers in Texas since statewide weather records began in Introduction 1 1895. Rainfall totals between 10 and 15 inches across Central Texas and 17 to Weather Summary 1 18 inches in the coastal counties made this the wettest November on record for Nov. 14 - 19: High- 1 Austin-Camp Mabry and Victoria (See land Lakes Basin Table 1). Across the Colorado River ba- sin, there were three distinct periods of Nov. 20 - 21: Coastal 3 very heavy rain, severe storms and Plains flooding that impacted different portions of the Colorado River basin. The chang- Nov. 22 - 23: Colo- ing patterns of heavy rainfall and flood rado River Basin 4 runoff required LCRA to constantly evalu- from Austin to ate conditions and adjust flood control Columbus Figure 1 — NOAA Satellite Image, Nov. 22, 2004 operations on the Highland Lakes. On Flood Control Opera- Nov. 24, Lake Travis reached a peak 5 elevation of 696.7 feet above mean sea level (msl), its highest level since June 1997 and the fifth highest tions level on record. The Colorado River at Wharton reached a stage of 48.26 feet, its highest level since Octo- Summary 6 ber 1998 and the ninth highest level on record. Flood control operations continued on the Highland Lakes for three months, from Nov. 17, 2004 until Feb. 17, 2005. Rainfall Statistics 7 Weather Summary 9 River Conditions November’s unusually wet weather was the result of a series of low pressure troughs moving across Texas from the southwestern United States. -

The DTMP19 Hospitality Manual

TOURNAMENT STAFF Below are the names and email addresses of the Dell Technologies Match Play Staff. Please do not hesitate to reach out with any questions. We are here to ensure you and your guests have an enjoyable experience. Jordan Uppleger Kris Devlin Executive Director Sales Manager Office: 512-949-5881 Cell: 512-803-0613 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Callie Gibson Geoff Hill Senior Tournament Services Manager Operations Manager Cell: 520-906-7447 Cell: 520-591-1714 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Rosalyn Barnett Devin Whalen Tournament Coordinator Operations Intern Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Zoe Margolis Tournament Services Intern Office: 512-949-5885 Email: [email protected] Address: 3600 N. Capital of Texas Highway Building B, Suite 230 Austin, TX 78746 FAN VILLAGE U WC 1. FIRST AID & SPECTATOR INFO/LOST & FOUND 2. FAN SHOP-MERCHANDISE TENT MC 3. DELL TECHNOLOGIES FAN EXPERIENCE 4. LOCAL FOOD VENDORS OAK GROVE ON SIX K 8 E 7 6 5 5. TAPS & TACOS/CRAFT BEER 6. LOCAL FOOD VENDOR 7. COWBOY CANTINA R 8. VIDEO BOARD F K LAKE HOUSE CHALET O MC G B PRESENTED BY MICROSOFT U UBER L P PRESENTED BY BAYLOR PICK-UP/DROP-OFF PRESENTED BY AVIS SCOTT & WHITE HEALTH H M Q D I WATERLOO E CAPITAL CLUB J N R PRESENTED BY HOTEL VAN ZANDT TERRACE TOURNAMENT FACT SHEET Date Tournament History March 27-31, 2019 Year Winner Site 1999 Jeff Maggert La Costa Resort & Spa Site 2000 Darren Clarke La Costa Resort & Spa Austin Country Club 2001 -

Water Quality of Lake Austin and Town Lake, Austin, Texas

WATER QUALITY OF LAKE AUSTIN AND TOWN LAKE, AUSTIN, TEXAS By Freeman L. Andrews, Frank C. Wells, Wanda J. Shelby, and Emma M. McPherson U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-RESOURCES INVESTIGATIONS REPORT 88-4233 Prepared in cooperation with the CITY OF AUSTIN Austin, Texas 1988 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR MANUEL LUJAN, JR., Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports Water Resources Division Federal Center, Bldg. 810 8011 Cameron Rd., Bldg. 1 Box 25425 Austin, Texas 78753 Denver, CO 80225 -ii- CONTENTS Page Abstract 1 Introduction 3 Purpose and scope 3 Location, physiography, and drainage 3 Climate 7 Population 8 Hydrology 8 Methods of analysis 13 Classification of water-quality surveys 13 Statistical methods 13 Water qual ity 18 Thermal stratification 18 Dissolved oxygen 21 Dissolved trace elements 28 Total nutrients 30 Nitrogen 37 Phosphorus 42 Dissolved solids, chloride, sulfate, and hardness 47 Monthly loads of dissolved solids 54 Indicator bacteria 58 Effects of stormwater runoff on water quality in Lake Austin and Town Lake 63 Suitability of water as a public supply 68 Effectiveness of sampling program and potential changes 76 Conclusions 76 References 79 Supplemental information 80 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1. Map showing location of highland lakes 4 2. Map showing location of water-quality data-collection sites on Lake Austin and Town Lake 5 3-38. Graphs showing: 3. Mean monthly precipitation at Austin, Texas, Municipal Airport, 1900-76 9 4.