Distribution of Nabarlek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHYTOCHEMICAL ASSESSMENT on N-HEXANE EXTRACT and FRACTIONS of Marsilea Crenata Presl

Trad. Med. J., May - August 2016 Submitted : 14-04-2016 Vol. 21(2), p 77-85 Revised : 25-07-2016 ISSN : 1410-5918 Accepted : 05-08-2016 PHYTOCHEMICAL ASSESSMENT ON N-HEXANE EXTRACT AND FRACTIONS OF Marsilea crenata Presl. LEAVES THROUGH GC-MS ANALISIS FITOKIMIA EKSTRAK N-HEKSANA DAN FRAKSI DAUN Marsilea crenata Presl. DENGAN GC-MS "µ≤®°Æ -°ï°≤©¶1*, Mangestuti Agil1 and Hening Laswati2 1Department of Pharmacognocy and Phytochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia 2Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medicine, Airlangga University, Surabaya, Indonesia ABSTRACT Estrogen deficiency causes various health problems in postmenopausal women, including osteoporosis. Phytoestrogen emerged as a potential alternative of estrogen with minimum side effects. Green clover (Marsilea crenata Presl.) is a typical plant in East Java which suspected contains estrogen-like substances. The aim of this research was to report the phytochemical properties of M. crenata using GC-MS as a preliminary study. M. crenata leaves were dried and extracted with n-hexane, then separated using vacuum column chromatography to get four fractions, after that the n-hexane extract and four fractions were identified with GC-MS. The results of GC-MS analysis showed some compounds contained in M. crenata leaves like monoterpenoid, diterpenoid, fatty acid compounds, and other unknown compounds. The results obtained in this research indicated a promising potential of M. crenata as medicinal plants, especially as antiosteoporotic agent. Keywords: Marsilea crenata Presl., phytochemical, antiosteoporosis, GC-MS ABSTRAK Defisiensi estrogen menyebabkan berbagai masalah kesehatan pada wanita pascamenopause, salah satunya osteoporosis. Fitoestrogen muncul sebagai alternatif yang potensial pengganti estrogen dengan efek samping minimal. -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

State of Australia's Threatened Macropods

State of Australia’s threatened macropods WWF-Australia commissioned a report into the state of Australia’s threatened macropods. The report summarises the status of threatened macropod species within Australia and identifies a priority list of species on which to focus further gap analysis. This information will inform and guide WWF in future threatened species conservation planning. The threatened macropods of Australia have been identified by WWF as a group of threatened species of global significance. This is in recognition of the fact that kangaroos and wallabies are amongst the most recognisable species in the world, they have substantial cultural and economic significance and significant rates of species extinction and decline means the future for many of the remaining species is not certain. Seventy-six macropod species are listed, or in the process of being listed, on the IUCN red-list. A total of forty-two of these species, or more than 50 per cent, are listed as threatened at some level. Threatened macropod species were ranked according to three criteria: • Conservation status, which was determined from four sources: IUCN Red List, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999), State legislation, IUCN Global Mammal Assessment Project • Occurrence within an identified WWF global priority ecoregion • Genetic uniqueness Summary of threatened macropods Musky rat kangaroo The musky rat kangaroo is a good example of how protected areas can aid in securing a species’ future. It is generally common within its small range and the population is not declining. It inhabits rainforest in wet tropical forests of Far North Queensland, and large tracts of this habitat are protected in the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area of Far North Queensland. -

Learning Through Country: Competing Knowledge Systems and Place Based Pedagogy’

'Learning through Country: Competing knowledge systems and place based pedagogy’ William Patrick Fogarty 2010 'Learning through Country: Competing knowledge systems and place based pedagogy’ A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University William Patrick Fogarty September 2010 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, William Patrick Fogarty, declare that this thesis contains only my original work except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. This thesis contains an extract from a jointly authored paper (Fordham et al. 2010) which I made an equal contribution to and is used here with the express permission of the other authors. This thesis does not exceed 100,000 words in length, exclusive of footnotes, tables, figures and appendices. Signature:………………………………………………………… Date:……………………… Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES, FIGURES AND PHOTOGRAPHS..................................................................III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………………………………V DEDICATION .................................................................................................................................... VII ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... VIII LIST OF ACRONYMS.........................................................................................................................X CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHOD ..............................................................................1 -

Conservation Advice Petrogale Concinna Monastria Nabarlek

THREATENED SPECIES SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Established under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 The Minister approved this conservation advice and included this species in the Endangered category, effective from 3/12/15 Conservation Advice Petrogale concinna monastria nabarlek (Kimberley) Note: The information contained in this conservation advice was primarily sourced from ‘The Action Plan for Australian Mammals 2012’ (Woinarski et al., 2014). Any substantive additions obtained during the consultation on the draft are cited within the advice. Readers may note that conservation advices resulting from the Action Plan for Australian Mammals show minor differences in formatting relative to other conservation advices. These reflect the desire to efficiently prepare a large number of advices by adopting the presentation approach of the Action Plan for Australian Mammals, and do not reflect any difference in the evidence used to develop the recommendation. Taxonomy Conventionally accepted as Petrogale concinna monastria (Thomas, 1926). Three subspecies of Petrogale concinna have been described; the other two subspecies are P. c. concinna (nabarlek (Victoria River District)) and P. c. canescens (nabarlek (Top End)). Their validity has not been tested by modern genetic methods, and the geographic bounds (particularly of P. c. concinna and P. c. canescens) are not resolved (Woinarski et al., 2014). However, the subspecies have been accepted by the Australian Faunal Directory. Summary of assessment Conservation status Endangered: Criterion 2 B2(a),b(i)(ii)(iii)(iv)(v) Species can be listed as threatened under state and territory legislation. For information on the listing status of this species under relevant state or territory legislation, see http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl Reason for conservation assessment by the Threatened Species Scientific Committee This advice follows assessment of new information provided to the Committee to list Petrogale concinna monastria. -

Plants Diversity for Ethnic Food and the Potentiality of Ethno-Culinary Tourism Development in Kemiren Village, Banyuwangi, Indonesia

Journal of Indonesian Tourism and doi: 10.21776/ub.jitode.2017.005.03.04 Development Studies E-ISSN : 2338-1647 http://jitode.ub.ac.id Plants Diversity for Ethnic Food and the Potentiality of Ethno-culinary Tourism Development in Kemiren Village, Banyuwangi, Indonesia 1* 2 2 Wahyu Kusumayanti Putri , Luchman Hakim , Serafinah Indriyani 1Master Program of Biology, Faculty of Mathematic and Natural Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia 2Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematic and Natural Sciences, University of Brawijaya, Malang, Indonesia Abstract Recent rapid grow of culinary tourism has significant potential contribution to enhancing biodiversity conservation especially biodiversity of local plant species for local food and food preparation tradition in local community. Ethnic food has been explored as one of the indigenous resources for community-based tourism, in which it is important in community development and biodiversity conservation. The aim of the study was to describe the involvement of plant in local cuisine and the concept of ethno-culinary tourism products development. The research was based on ethno- botanical study through observation and interviews with local community and tourism stakeholder in Kemiren Village, Banyuwangi. This study found that there was 108 ethnic food menu in Kemiren Village. There are 67 species of 35 plant family were used in local cuisine. Kemiren Village has been identified rich in term of traditional culinary which are able to be developed as attractive cuisine in culinary tourism. Keywords: culinary tourism,ethnicfood, Kemiren Village. INTRODUCTION* culinary tourism. The development of culinary Special interest tourism recently grows tourism sector in Banyuwangi relevant with the significantly, and many developing countries with recent trend of tourism development in abundance nature and culture are the favorite Banyuwangi Regency. -

The Nutrition, Digestive Physiology and Metabolism of Potoroine Marsupials — General Discussion Ҟ193

THE NUTRITION, DIGESTIVE PHYSIOLOGY AND METABOLISM OF POTOROINE MARSUPIALS A thesis submitted to The University of New England for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Ian Robert Wallis Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Nutrition 1990 000OO000 TO ... Streetfighter, Rufous and the Archbishop . three flamboyant potoroine marsupials. o oo00 oo o PREFACE The studies presented in this thesis were completed by the author while a part-time student in the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Nutrition, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia. Assistance given by other persons is indicated in the text or in the list of acknowledgements. All references cited are included in the bibliography. The work is otherwise original. I certify that the substance of this thesis has not already been submitted for any degree and is not being currently submitted for any other degree. I certify that any help received in preparing this thesis, and all sources used have been acknowledged in the thesis. August 1990 I R Wallis 000OO000 11 CONTENTS Prefaceҟ i Acknowledgementsҟ viii Abstractҟ x List of scientific namesҟ xiv List of tablesҟ xvi List of figuresҟ xx Chapter One Introduction: The Potoroinae, a neglected group of marsupialsҟ 1 Chapter Two Herbivory: Problems and solutions 2.1 Diet, body size, gut capacity and metabolic requirements 4 2.2 Gut structure: how herbivores obtain nourishment 6 2.2.1 Mastication 7 2.2.2 Salivary glands 8 2.2.3 Gut capacity 10 2.2.4 Gastric sulcus 10 2.2.5 Epithelia 11 2.2.6 Separation of digesta -

Marsilea Crenata Ethanol Extract Prevents Monosodium Glutamate Adverse Effects on the Serum Levels of Reproductive Hormones

Veterinary World, EISSN: 2231-0916 RESEARCH ARTICLE Available at www.veterinaryworld.org/Vol.14/June-2021/16.pdf Open Access Marsilea crenata ethanol extract prevents monosodium glutamate adverse effects on the serum levels of reproductive hormones, sperm quality, and testis histology in male rats Sri Rahayu , Riska Annisa , Ivakhul Anzila , Yuyun Ika Christina , Aries Soewondo , Agung Pramana Warih Marhendra and Muhammad Sasmito Djati Department of Biology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Brawijaya University, Malang 65145, East Java, Indonesia. Corresponding author: Sri Rahayu, e-mail: [email protected] Co-authors: RA: [email protected], IA: [email protected], YIC: [email protected], AS: [email protected], APWM: [email protected], MSD: [email protected] Received: 28-12-2020, Accepted: 28-04-2021, Published online: 15-06-2021 doi: www.doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2021.1529-1536 How to cite this article: Rahayu S, Annisa R, Anzila I, Christina YI, Soewondo A, Marhendra APW, Djati MS (2021) Marsilea crenata ethanol extract prevents monosodium glutamate adverse effects on the serum levels of reproductive hormones, sperm quality, and testis histology in male rats, Veterinary World, 14(6): 1529-1536. Abstract Background and Aim: Marsilea crenata is an aquatic plant that contains high antioxidants level and could prevent cell damages caused by free radicals. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of M. crenata ethanol extract on luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone levels, sperm quality, and testis histology of adult male rats induced by monosodium glutamate (MSG). Materials and Methods: This study randomly divided 48 male rats into eight groups (n=6): control group; MSG group (4 mg/g body weight [b.w.] for 30 days); MS1, MS2, and MS3 groups (4 mg/g b.w. -

Northern Territory NT Page 1 of 204 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region Northern Territory, Northern Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

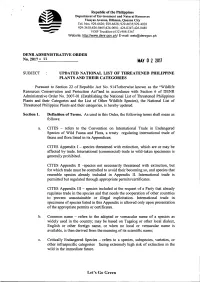

DENR Administrative Order. 2017. Updated National List of Threatened

Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources Visayas Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Tel. Nos. 929-6626; 929-6628; 929-6635;929-4028 929-3618;426-0465;426-0001; 426-0347;426-0480 VOiP Trunkline (632) 988-3367 Website: http://www.denr.gov.ph/ E-mail: [email protected] DENR ADMINISTRATIVE ORDER No. 2017----------11 MAVO 2 2017 SUBJECT UPDATED NATIONAL LIST OF THREATENED PHILIPPINE PLANTS AND THEIR CATEGORIES Pursuant to Section 22 of Republic Act No. 9147otherwise known as the "Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act"and in accordance with Section 6 of DENR Administrative Order No. 2007-01 (Establishing the National List of Threatened Philippines Plants and their Categories and the List of Other Wildlife Species), the National List of Threatened Philippine Plants and their categories, is hereby updated. Section 1. Definition of Terms. As used in this Order, the following terms shall mean as follows: a. CITES - refers to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, a treaty regulating international trade of fauna and flora listed in its Appendices; CITES Appendix I - species threatened with extinction, which are or may be affected by trade. International (commercial) trade in wild-taken specimens is generally prohibited. CITES Appendix II -species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but for which trade must be controlled to avoid their becoming so, and species that resemble species already included in Appendix II. International trade is permitted but regulated through appropriate permits/certificates. CITES Appendix III - species included at the request of a Party that already regulates trade in the species and that needs the cooperation of other countries to prevent unsustainable or illegal exploitation. -

Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS Visit Us at the Following Book Fairs

Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS Visit us at the following book fairs: San Francisco Antiquarian Book, Print & Paper Fair 2 - 3 February 2018 California International Antiquarian Book Fair 9 - 11 February 2018 New York International Antiquarian Book Fair 8 - 11 March 2018 Tokyo International Antiquarian Book Fair 23 - 25 March 2018 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS 720 High Street Armadale Melbourne VIC 3143 Australia +61 3 9066 0200 [email protected] To add your details to our email list for monthly New Acquisitions, visit douglasstewart.com.au © Douglas Stewart Fine Books 2018 Items in this catalogue are priced in US Dollars Front cover p. 37 (#17095). Title page p. 66 (#17314). Back cover p. 14 (#16533). Catalogue 75 DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS MELBOURNE • AUSTRALIA 2 McGovern, Melvin P. 1. Specimen pages of Korean movable types. Collected & described by Melvin P. McGovern. Los Angeles : Dawson’s Book Shop, 1966. Colophon: ‘Of this edition, three hundred copies have been printed for sale. Of these, ninety- five copies comprise the Primary Edition and are numbered from I to XCV. The remaining copies are numbered from 96 through 300. This copy is number [in manuscript] A, out of series (Tuttle) / For Mr. & Mrs Charles Tuttle who have heard much & seen nothing these five years. Peter Brogren‘. Folio, original quarter white cloth over embossed handmade paper covered boards, frontispiece, pp 73, with 22 mounted specimen leaves from 15th-19th centuries, identified in Korean as well as in English; bibliography; housed in a cloth slipcase; a fine presentation copy from the book’s printer, Peter Brogren of The Voyagers’ Press, Tokyo, produced out of series for the publisher and bookseller Charles E. -

Tropical Australian Water Plants Care and Propagation in Aquaria

Tropical Australian Water Plants Care and propagation in Aquaria Dave Wilson Aquagreen Phone – 08 89831483 or 0427 212 782 Email – [email protected] 100 Mahaffey Rd Howard Springs NT 0835 Introduction There is a growing interest in keeping native fishes and plants. Part of the developing trend in keeping aquaria and ponds is to set up a mini habitat for selected species from the one place and call it a biotope. Some enthusiasts have indicated that in recent times there is not much technical information for beginners about native Australian aquatic plant growing. Generally, if you can provide good conditions for the plants, the other inhabitants, fish, crustaceans and mollusc will be happy. This will set out water quality management, fertiliser and its management, describe an aquarium system that incorporates technology to achieve a nice aquarium. The fourth part will describe some native plants that can be trialled in the aquarium. Soft water plants Hard Water plants Part 1 - Water Quality - Measuring and Management Most people are familiar with pH, alkalinity, hardness, salinity and temperature. The system described here needs control over these parameters which link in with the fertilisers required for good plant growth. A couple of others that can be measured are phosphate and nitrate. Fertilisers produced from feeding fish can be used and are calculated into the system but are usually in the wrong proportions for good plant growth management. A fresh water planted aquarium does better with a 25% to 50% water change per week, test the water you use for the change to make sure that it is better than the water you have already.