Historical Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Origins of Newspaper Competition in Pre

Thomas Jefferson and the Origins of Newspaper Competition in Pre- Revolutionary Virginia Original research paper submitted to The History Division of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, 2007 AEJMC Convention Roger P. Mellen George Mason University June 2007 Thomas Jefferson and the Origins of Newspaper Competition in Pre-Revolutionary Virginia “Until the beginning of our revolutionary dispute, we had but one press, and that having the whole business of the government, and no competitor for public favor, nothing disagreeable to the governor could be got into it. We procured Rind to come from Maryland to publish a free paper.” Thomas Jefferson1 Great changes came to the printing business in Virginia in 1765. About the time that Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a second printer was encouraged to open another shop in Williamsburg, marking the beginnings of competition in that field. This was an important watershed for the culture and government of the colony, for it signified a shift in the power structure. Control of public messages began to relocate from the royal government to the consumer marketplace. This was a transformation that had a major impact on civic discourse in the colony. Despite such significance, the motivations behind this change and the relevance of it have often been misunderstood. For example, it is widely accepted that Thomas Jefferson was responsible for bringing such print competition to Virginia. This connection has been constantly repeated by historians, as has early print historian Isaiah Thomas’s contention that Jefferson confirmed this in a letter written specifically from the former president to Thomas. -

Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2020 Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia Ana F. Edwards Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6362 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Robert Cowley: Living Free During Slavery in Eighteenth-Century Richmond, Virginia A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts from the Department of History at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Ana Frances Edwards Wilayto Bachelor of Arts, California State Polytechnic University at Pomona, 1983 Director of Record: Ryan K. Smith, Ph. D., Professor, Department of History, Virginia Commonwealth University Adviser: Nicole Myers Turner, Ph. D., Professor, Department of Religious Studies, Yale University Outside Reader: Michael L. Blakey, Ph. D., Professor, Department of Anthropology, College of William & Mary Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia June 2020 © Ana Frances Edwards Wilayto 2020 All Rights Reserved 2 of 115 For Grandma Thelma and Grandpa Melvin, Grandma Mildred and Grandpa Paul. For Mom and Dad, Allma and Margit. For Walker, Taimir and Phil. Acknowledgements I am grateful to the professors--John Kneebone, Carolyn Eastman, John Herman, Brian Daugherty, Bernard Moitt, Ryan Smith, and Sarah Meacham--who each taught me something specific about history, historiography, academia and teaching. -

Slavery in Ante-Bellum Southern Industries

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier SLAVERY IN ANTE-BELLUM SOUTHERN INDUSTRIES Series C: Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 1: Mining and Smelting Industries Editorial Adviser Charles B. Dew Associate Editor and Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Slavery in ante-bellum southern industries [microform]. (Black studies research sources.) Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the Duke University Library / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Randolph Boehm—ser. B. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—ser. C. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Martin P. Schipper. 1. Slave labor—Southern States—History—Sources. 2. Southern States—Industries—Histories—Sources. I. Dew, Charles B. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Duke University. Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm). V. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library. Southern Historical Collection. VI. Virginia Historical Society. HD4865 306.3′62′0975 91-33943 ISBN 1-55655-547-4 (ser. C : microfilm) CIP Compilation © 1996 by University Publications -

The British Empire in the Atlantic: Nova Scotia, the Board of Trade, and the Evolution of Imperial Rule in the Mid-Eighteenth Century

The British Empire in the Atlantic: Nova Scotia, the Board of Trade, and the Evolution of Imperial Rule in the Mid-Eighteenth Century by Thomas Hully Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MA degree in History University of Ottawa © Thomas Hully, Ottawa, Canada, 2012 ii Abstract The British Empire in the Atlantic: Nova Scotia, the Board of Trade, and the Evolution of Imperial Rule in the Mid-Eighteenth Century Thomas Hully Dr. Richard Connors Submitted: May 2012 Despite considerable research on the British North American colonies and their political relationship with Britain before 1776, little is known about the administration of Nova Scotia from the perspective of Lord Halifax’s Board of Trade in London. The image that emerges from the literature is that Nova Scotia was of marginal importance to British officials, who neglected its administration. This study reintegrates Nova Scotia into the British Imperial historiography through the study of the “official mind,” to challenge this theory of neglect on three fronts: 1) civil government in Nova Scotia became an important issue during the War of the Austrian Succession; 2) The form of civil government created there after 1749 was an experiment in centralized colonial administration; 3) This experimental model of government was highly effective. This study adds nuance to our understanding of British attempts to centralize control over their overseas colonies before the American Revolution. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the Ontario Graduate Scholarship Program for providing the funding which made this dissertation possible, as well as the University of Ottawa’s Department of History for providing me with the experience of three Teaching Assistantships. -

Un-Burkean Economic Policy of Edmund Burke E L I Z a B E T H L a MB E R T , Edmund Burke of Beaconsfield R O B E R T H

STUDIES IN BURKE AND HIS TIME AND HIS STUDIES IN BURKE I N THE N EXT I SS UE ... S TEVEN P. M ILLIE S STUDIES IN The Inner Light of Edmund Burke A N D REA R A D A S ANU Edmund Burke’s Anti-Rational Conservatism R O B ERT H . B ELL The Sentimental Romances of Lawrence Sterne AND HIS TIME J.D. C . C LARK A Rejoinder to Reviews of Clark’s Edition of Burke’s Reflections R EVIEW S O F M ICHAEL B ROWN The MealVirgil at the MartinSaracen’s Head: Nemoianu Edmund Burke F . P. L OCK Edmund Burke Volume II: 1784 – 1797 , Burke on the Goodnessand the of Scottish Beauty Literati and the Virtue of Taste S EAN P ATRICK D ONLAN , Edmund Burke’s Irish Identities M ICHAELRalph F UNK E. Ancil D ECKAR D Wonder and Beauty in Burke’s Philosophical Enquiry N EIL M C A RTHUR , David Hume’s Political Theory The Un-Burkean Economic Policy of Edmund Burke E LIZA B ETH L A MB ERT , Edmund Burke of Beaconsfield R O B ERT H . B ELL Fool for Love: The SentimentalJohn Boersma Romances of Laurence Sterne Toward a Burkean Theory S TEVEN P. M ILLIE S The Inner Lightof Constitutional of Edmund Burke: Interpretation A Biographical Approach to Burke’s Religious Faith and Epistemology STUDIES IN José Ramón García-Hernández Edmund Burke’s Whig Response VOLUME 22 2011 to the Eighteenth-Century Crisis of Legitimacy REVIEW S O F AND HIS TIME F.P.LOCK, Edmundreviews Burke: Vol. -

Dinwiddie Family Records

DINWIDDIE FAMILY RECORDS with especial attention to the line of William Walthall Dinwiddie 1804-1882 Compiled and Edited by ELIZABETH DINWIDDIE HOLLADAY KING LINDSAY PRINTING CORPORATION CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 1957 AFTER READING GENEALOGY Williams and Josephs, Martha, James, and John, The generations' rhythmic flow moves on; Dwellers in hills and men of the further plains, Pioneers of the creaking wagon trains, Teachers, fighters, preachers, tillers of the earth, Buried long in the soil that gave them birth. New times, new habits; change is everywhere. New dangers tour the road, new perils ride the air. Our day is late and menacing. The lateness Breeds fatalistic weariness until Joy shrivels into fear. But faith knows still Each new-born child renews the hope for greatness. LmllARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG NUMBER 57-9656 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Preface Edgar Evans Dinwiddie, my father, for many years collected data on the history of his family. His niece, Emily W. Dinwiddie, became interested and they shared their findings. In the last years of his life, when he was an invalid, she combined their most important papers in to one voluminous file. After both of them died I found myself in possession of the fruits of their labors, and the finger of Duty seemed to be pointing my way. From their file I learned of the long search made in many places, of the tedious copying of old records, and in many cases the summarizing of data in answering in quiries from others. Also Emily had made typed copies of much of the handwritten material. -

Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/23/9 Image Reference:0021 uolonei Jones', [This Document is the Property of His Britannic Majesty's Government.] 72 Printed for the Wor Cabinet. March 15)19. SECRET. WA R CABINET, 534. Minutes of a Meeting of the War Cabinet held in the Leader of the Housed Room, House of Commons, on Wednesday, February 19, 1919, at 5 "30 P.M. Present : THE PRIME MINISTER (in the Chair). The Right Hon. A. CHAMBERLAIN, M.P. The Right Hon. SIR E. GEDOES, G.B.E., G.C.B., M.P. The following were also present : The Right Hon. W . LONG, M.P., First The Right Hon. W. S. CHURCHILL, M.P., Lord of the Admiralty. Secretary of State for War (for Minutes 2 and 3). The Right Hon. E. S. MONTAGU, M.P., Secretary of State for India. Major-General J. E. B. SEELY, C.B., C.M.G., The Right Hon. E. SHORTT, K.C.. M.P., j D.S.O., M.P., Under-Secretary of State Secretary of State for Home Affairs. for the Air Force (for Minutes 1 and 2). The Right Hon. C. ADDISON, M.D., M.P., The Right Hon. R. MUNRO, K.C., M.P., President of the Local Government j Secretary ei "Stale"for Scotland. Board. The Right Hon. J . I. MACPHERSON, M.P., The Right Hon. SIR A. C. GEDDES, K.C.B., i Chief Secretary for Ireland. M.P., Minister of Reconstruction and j National Service. The Right Hon. LORD ERNLE, M.V.O., The Right Hon. -

A Legendary Sandwich for an Infamous Earl

A Legendary Sandwich for an Infamous Earl Representing the Sandwich in Legend and Cookery Literature The first sandwich consisted of two slices of bread with a layer of ham between. The legend runs that it was eaten by John Montagu, the fourth Earl of Sandwich (Woodman 1934: 9). By: Noah J.A. Morritt Introduction Sitting around a dimly lit, smoky, boisterous card table, John Montagu, the reputedly infamous Fourth Earl of Sandwich, is reported to have made an important culinary innovation. Unwilling to abandon his hand or the thrill of the competition, the Earl ordered a servant to bring him pieces of meat enclosed between two pieces of bread. Free to play his cards with one hand and eat with the other, he had created a dish worthy of his reputation; that is to say, the reputation that later writers and cookery book authors created and reported in their narrative accounts of the Earl’s character, his status as an eccentric gambler, and his culinary invention. Looking to establish the aristocratic pedigree and historical lineage of the sandwich, cook book authors in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Britain reported the legend of the Earl’s invention of the sandwich, often as a historical anecdote to accompany their recipes. As legend, narrative accounts of the Earl ordering slices of meat to be brought to his gaming table served between two pieces of bread are presented as true or, at the very least, plausible. Often defined as narratives told as true (Bascom 1965), legends are exemplary prose narratives formulated from, and embedded within a group’s system of belief (Dégh 2001; Dégh and Vázsonyi 1976; Georges 1971; Smith 1994; Tangerlini 1990). -

Edmund Burke, Miscellaneous Writings (Select Works Vol. 4) (1874)

Burke_0005.04 09/15/2005 09:39 AM THE ONLINE LIBRARY OF LIBERTY © Liberty Fund, Inc. 2005 http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/index.php EDMUND BURKE, MISCELLANEOUS WRITINGS (SELECT WORKS VOL. 4) (1874) URL of this E-Book: http://oll.libertyfund.org/EBooks/Burke_0005.04.pdf URL of original HTML file: http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/HTML.php?recordID=0005.04 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Burke was an English political philosopher who is often seen as laying the foundations of modern conservatism. Although he supported the American colonies in the revolution against the British crown, he strongly opposed the French Revolution, the rise of unbridled democracy, and the growing corruption of government. ABOUT THE BOOK This volume contains some of Burke’s speeches on parliamentary reform, on colonial policy in India, and on economic matters. THE EDITION USED Select Works of Edmund Burke. A New Imprint of the Payne Edition. Foreword and Biographical Note by Francis Canavan, 4 vols (Indianapolis: :Liberty Fund, 1999). COPYRIGHT INFORMATION The copyright to this edition, in both print and electronic forms, is held by Liberty Fund, Inc. FAIR USE STATEMENT This material is put online to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. Unless otherwise stated in the Copyright Information section above, this material may be used freely for educational and academic purposes. It may not be used in any way for profit. http://oll.libertyfund.org/Home3/EBook.php?recordID=0005.04 Page 1 of 175 Burke_0005.04 09/15/2005 09:39 AM It may not be used in any way for profit. -

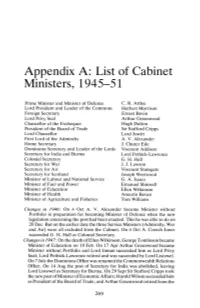

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51

Appendix A: List of Cabinet Ministers, 1945-51 Prime Minister and Minister of Defence C. R. Attlee Lord President and Leader of the Commons Herbert Morrison Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin Lord Privy Seal Arthur Greenwood Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton President of the Board of Trade Sir Stafford Cripps Lord Chancellor Lord Jowitt First Lord of the Admiralty A. V. Alexander Home Secretary J. Chuter Ede Dominions Secretary and Leader of the Lords Viscount Addison Secretary for India and Burma Lord Pethick-Lawrence Colonial Secretary G. H. Hall Secretary for War J. J. Lawson Secretary for Air Viscount Stansgate Secretary for Scotland Joseph Westwood Minister of Labour and National Service G. A. Isaacs Minister of Fuel and Power Emanuel Shinwell Minister of Education Ellen Wilkinson Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries Tom Williams Changes in 1946: On 4 Oct A. V. Alexander became Minister without Portfolio in preparation for becoming Minister of Defence when the new legislation concerning the post had been enacted. This he was able to do on 20 Dec. But on the earlier date the three Service Ministers (Admiralty, War and Air) were all excluded from the Cabinet. On 4 Oct A. Creech Jones succeeded G. H. Hall as Colonial Secretary. Changes in 1947: On the death of Ellen Wilkinson, George Tomlinson became Minister of Education on 10 Feb. On 17 Apr Arthur Greenwood became Minister without Portfolio and Lord Inman succeeded him as Lord Privy Seal; Lord Pethick-Lawrence retired and was succeeded by Lord Listowel. On 7 July the Dominions Office was renamed the Commonwealth Relations Office.