Steve Campbell-Wright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity Brochure “Ready to Be Different”

Ready to be different “At Daimler, we don’t just build the best cars – we also offer the best models that enable individual solutions for the perfect balance between our professional and our private lives. The world we live and work in is undergoing unprecedented change. Creativity, flexibility and responsiveness are the top skills going forward into the future. We are working hard to create a culture fostering and enabling these competencies. A culture in which new ideas can florish – to shape the future of mobility for customers around the globe.” Wilfried Porth Member of the Board of Management of Daimler AG, Human Resources and Director of Labor Relations, IT & Mercedes-Benz Vans 10 Diversity is what drives us Imagine the following scene: An Italian, an Ethiopian, a Turk, a Chinese lady and a few Swabians meet... Jokes actually begin like this, but in our manufacturing plants this is how the early shift begins. And even if the scene might seem a bit contrived, you can actually encounter this at Daimler. We were one of the first companies in our industry to firmly establish Diversity Management in our strategy back in 2005. We don’t just tolerate diversity, we strive for it: About 289,000 people from 160 countries work side-by-side at Daimler. Our understanding of diversity includes much more than country of origin: In our plants you are just as likely to meet a designer in a wheelchair, a refugee doing a bridge internship and a transgender colleague from vehicle development, as a 16 year-old apprentice or a 60 year-old quality manager. -

Index to Aerial Photographs in the Worcestershire Photographic Survey

Records Service Aerial photographs in the Worcestershire Photographic Survey Aerial photographs were taken for mapping purposes, as well as many other reasons. For example, some aerial photographs were used during wartime to find out about the lie of the land, and some were taken especially to show archaeological evidence. www.worcestershire.gov.uk/records Place Description Date of Photograph Register Number Copyright Holder Photographer Abberley Hall c.1955 43028 Miss P M Woodward Abberley Hall 1934 27751 Aerofilms Abberley Hills 1956 10285 Dr. J.K.S. St. Joseph, Cambridge University Aldington Bridge Over Evesham by-Pass 1986 62837 Berrows Newspapers Ltd. Aldington Railway Line 1986 62843 Berrows Newspapers Ltd Aldington Railway Line 1986 62846 Berrows Newspapers Ltd Alvechurch Barnt Green c.1924 28517 Aerofilms Alvechurch Barnt Green 1926 27773 Aerofilms Alvechurch Barnt Green 1926 27774 Aerofilms Alvechurch Hopwood 1946 31605 Aerofilms Alvechurch Hopwood 1946 31606 Aerofilms Alvechurch 1947 27772 Aerofilms Alvechurch 1956 11692 Aeropictorial Alvechurch 1974 56680 - 56687 Aerofilms W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Ashton-Under-Hill Crop Marks 1959 21190 - 21191 Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Crop Marks 1956 21252 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Crop Marks 1956 - 1957 21251 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Astley Roman Fort 1957 21210 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. Aston Somerville 1974 56688 Aerofilms Badsey 1955 7689 Dr. J.K.S. St. Joseph, Cambridge University Badsey 1967 40338 Aerofilms Badsey 1967 40352 - 40357 Aerofilms Badsey 1968 40944 Aerofilms Badsey 1974 56691 - 56694 Aerofilms Beckford Crop Marks 1959 21192 W.A. Baker, Birmingham University Extra - Mural Dept. -

Evesham to Pershore (Via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (Via Bredon Hill)

Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (via Bredon Hill) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 19th July 2019 15th Nov. 2018 07th August 2021 Current status Document last updated Sunday, 08th August 2021 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2021, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton and Bredon Hills) Start: Evesham Station Finish: Pershore Station Evesham station, map reference SP 036 444, is 21 km south east of Worcester, 141 km north west of Charing Cross and 32m above sea level. Pershore station, map reference SO 951 480, is 9 km west north west of Evesham and 30m above sea level. -

Green Infrastructure Framework 3: Access and Recreation

Planning for a Multifunctional Green Infrastructure Framework in Worcestershire Green Infrastructure Framework 3: Access and Recreation May 2013 Find out more online: www.worcestershire.gov.uk/ Contents Contents 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 2 Chapter 2: Context 4 Chapter 3: Informal Recreation Provision in Worcestershire 6 Chapter 4: Carrying Capacity of GI Assets 16 Chapter 5: Green Infrastructure Assets and Indices of Multiple Deprivation 24 Chapter 6: Pressure from Development 38 Chapter 7: Future Needs and Opportunities 42 Chapter 8: Summary and Conclusions 53 Appendix 1: Sub-regional assets covered by the study 54 Appendix 2: Linear sub-regional GI assets 56 Appendix 3: Accessible Natural Greenspace Standard 57 Appendix 4: Proposed Housing Development Sites in the County 58 1 Chapter 1: Introduction Preparation of this Green Infrastructure Framework Document 3 Access and Recreation has been led by the County Council's Strategic Planning and Environmental Policy team. The framework has been endorsed by the Worcestershire Green Infrastructure Partnership. Partnership members include the Worcestershire Wildlife Trust, Natural England, Environment Agency, Forestry Commission, English Heritage, the County and District Councils and the Voluntary Sector. Background to the Framework The Green Infrastructure partnership is producing a series of 'framework documents' which provide the evidence base for the development of the GI Strategy. Framework Document 1 is an introduction to the concept of Green Infrastructure (GI) and also identified the need for the strategic planning of GI and the policy drivers that support the planning of GI at differing spatial scales. Framework Document 2 is an introduction to the natural environment landscape, biodiversity and historic environment datasets and developed the concept of GI Environmental Character Areas based on the quality and quantity of the natural environment assets. -

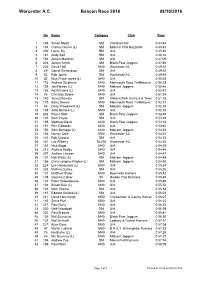

Worcester A.C. Beacon Race 2016 08/10/2016

Worcester A.C. Beacon Race 2016 08/10/2016 No Name Category Club Time 1 148 Simon Myatt SM Trentham RC 0:43:44 2 163 Ciaran Connor (L) SM Malvern Hills Buzzards 0:45:44 3 200 Henry Sly SM U/A 0:45:46 4 181 Andy Salt SM U/A 0:46:34 5 154 James Marshall SM U/A 0:47:05 6 234 James Smith SM Black Pear Joggers 0:47:46 7 222 David Hall M40 Worcester AC 0:49:38 8 49 Daniel Richardson SM U/A 0:49:52 9 52 Rob Jones SM Worcester AC 0:49:55 10 83 Nick Pryce-Jones (L) M40 U/A 0:50:03 11 173 Andrew Stephens M40 Monmouth Ross Trailblazers 0:50:35 12 199 Jon Newey (L) M40 Malvern Joggers 0:50:46 13 193 Keith Evans (L) M40 U/A 0:50:51 14 76 Christian Dowle M40 U/A 0:51:04 15 140 James Bewley SM Victoria Park Harriers & Tower Hamlets0:51:25 AC 16 170 Barry Davies M40 Monmouth Ross Trailblazers 0:52:31 17 48 Dave Woodward (L) SM Malvern Joggers 0:52:35 18 188 John Bristow (L) M40 U/A 0:52:36 19 202 Paul Childs SM Black Pear Joggers 0:52:49 20 120 Sam Payne SM U/A 0:53:29 21 109 Matthew Davis M40 Black Pear Joggers 0:53:32 22 151 Phil Edwards M40 U/A 0:53:40 23 190 Sam Burnage (L) M40 Malvern Joggers 0:53:54 24 153 Martyn Cole M50 Worcester AC 0:54:01 25 122 Rob Ciancio SM U/A 0:54:32 26 141 Luc Allberry MU/20 Worcester AC 0:54:36 27 162 Nick Biggs M40 U/A 0:54:39 28 213 Andrew Boddy M40 U/A 0:54:46 29 207 Andrew Lawson M40 U/A 0:54:47 30 137 Neil Watts (L) SM Malvern Joggers 0:54:49 31 156 Chris Langley-Waylen (L) SM Malvern Joggers 0:54:50 32 224 Lee Henderson (L) M40 U/A 0:55:04 33 233 Nathan Quilley SM U/A 0:55:06 34 131 Matthew Slater M40 Bournville -

Track Stars Align 1959 Podium-Finishing Protea Triumph & Mga Twin Cam Reunited

AC EMPIRE MODEL 12 THE TVR TALE LOTUS SEVEN AT 60 R47.00 incl VAT October 2017 TRACK STARS ALIGN 1959 PODIUM-FINISHING PROTEA TRIUMPH & MGA TWIN CAM REUNITED THE ROTOR ROUTE BACKYARD BRAWLERS NSU’S SUPER SMOOTH RO80 ALFA, BMW & FORD GROUP 1 RACERS KATJA POENSGEN | GOTTLIEB DAIMLER | MARIO MASSACURATI Porsche Classic_210x276.qxp_Layout 1 2017/09/07 11:09 AM Page 1 The best sounds for more than six decades. Hear them all at your Porsche Classic Partner. Porsche Centre Cape Town. As a Porsche Classic Partner, our goal is the maintenance and care of historic Porsche vehicles. With expertise on site, Porsche Centre Cape Town is dedicated CLASSIC to ensuring your vehicle continues to be what it has always been: 100% Porsche. Porsche Centre Cape Town Corner Century Avenue Our services include: and Summer Greens Drive, • Classic Sales Century City • Classic Body Repair Telephone 021 555 6800 • Genuine Classic Parts www.porschecapetown.com CONTENTS — CARS BIKES PEOPLE AFRICA — OCTOBER 2017 PETAL TO THE METAL THE FORWARD THINKER 03 Editor’s point of view 74 Talking with Gottlieb Daimler CLASSIC CALENDAR ORIGINALITY RULES 06 Upcoming events for 2017 80 Column – The Hurst Shifter NEWS & EVENTS THE GAME CHANGER 08 All the latest from the classic scene 82 Model review – CMC Talbot Lago Coupé LETTERS 22 Have your say BLAST FROM THE PAST 84 Track test – Nash MVW3 CARBS & COFFEE 26 RockStarCars THE DUST BUSTER 86 NRC – Classic Rally Class AN EMPIRICAL AC 30 AC Empire Model 12 MOVING HOUSE 88 Backseat Driver – TRACK STARS ALIGN A Female Perspective 36 Protea -

1961 Daimler SP 250 Sports Fibreglass Bodied 2 Seater with 2½ Litre V8 Engine

1961 Daimler SP 250 Sports Fibreglass bodied 2 seater with 2½ litre V8 engine This car dates from April 1961 and was originally sold in Wolverhampton. From 1974 to 1989 it was owned by the well-known Daimler specialist David Manners. It was then bought by the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust, and came to the Jaguar Daimler Heritage Trust in 1991. It was later refurbished in the original colour of Mountain Blue, although with red trim rather than grey, with the assistance of Jaguar's Special Vehicle Operations Department. By the late 1950s, the Daimler Company was in trouble. A confused model policy had led to dwindling sales. There was not much money available to invest in much-needed new models. However, a brace of new all-aluminium V8 engines, of 2½ litres and 4½ litres, designed by Edward Turner, were under development. The question was - in what cars should these engines be fitted? After trying to adapt a Vauxhall body for a new saloon, Daimler decided to launch the smaller of the new engines in a sports car, conceived with the American market in mind. The new car was in every respect a departure from traditional Daimler practice. The chassis was inspired by the Triumph TR3A, and the strikingly styled body was made from fibreglass. The new model was launched at the New York Motor Show in April 1959 and was at first called the Daimler Dart – until the Chrysler Corporation protested that they had this name registered for a Dodge, and Daimler was obliged to change their new model's name to SP 250. -

MJP PAYNE Page No. 1 of 1 the Miss

The Miss Phillips’s Conglomerate of the Malvern Hills - Where is Phillips’s original site? M. J. P. Payne Herefordshire & Worcestershire Earth Heritage Trust, Geological Records Centre, University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester WR2 6AJ ABSTRACT The discovery in 1842 of a Silurian beach deposit on the Malvern Hills was an important step in uncovering the geological history of the area. Knowledge of the site of this discovery has been lost for about a century but a number of possibilities have been put forward. In this paper, the documentary evidence is analysed and compared with the local geography and geology. The location of the discovery is unambiguously determined. 1. INTRODUCTION In 1842 Ann Phillips, the sister of the Survey geologist John Phillips, found fragments of a fossiliferous beach conglomerate on the Malvern Hills. This was soon followed by the discovery of the bed known now as the ‘Miss Phillips’s Conglomerate’. The exact location of this discovery has been a minor mystery for the last hundred or more years. This is an important site in the history of geological research in the Malvern Hills since it established the probable relationship between the igneous rocks of the hills and the Silurian sediments to the west. In particular, it appeared to demonstrate that Silurian sediments lay as a beach deposit upon what are now known to be Precambrian rocks, and therefore post-dated them. This ran counter to the prevailing view at the time, that the igneous rocks were intrusive, ‘trap’ rocks of a date later than the Silurian (Murchison, 1839). The true nature of the western boundary of the Precambrian rocks of the Malvern Hills has nevertheless been a topic of much controversy and varied opinions up to the present day (e.g. -

1 Dear Members Welcome to the First Newsletter of 2014

Volume: 2014 issue: 1 Dear Members Welcome to the first Newsletter of 2014 under my editorship. I first held this committee post during the 90’s and it was then produced on a typewriter (later a word-processor) and print items were cut, pasted in (literally), and then printed on Keith Bowley’s hand-fed photocopier! For graphic historians amongst you, the title page was hand drawn and featured type by Letraset. It has been asked why we bother with a club newsletter since social media and digital publishing now allow news to be disseminated quickly and efficiently. We believe there is still a purpose to be served by producing such a publication which brings all the news, features, results etc. that appear in other places (notably the website) into one document. Not all our membership regularly “surf” the website and some may just prefer catching up with club activities in this type of format. There are still a significant number of members who are not able to access information from the website at all. It is also quicker and easier for us to produce information in formats suitable for any member with specific disability requirements (large print etc.) from a document that has already been collated and formatted. With apologies to “Spitfire” Ales. So the newsletter will continue to carry news of club A plea from the Track & Field Team Captain events, fixtures, results of note, “pleas for help”, committee statements, coaching information and Our new Men’s Team Captain Jason Manton is anything else the membership would wish to include appealing to all track and field athletes to be available (unless of course, you let us know differently!) for selection this coming season. -

The Worcestershire Beacon Race Walk

The Worcestershire Beacon Race Short Walk The Worcestershire Beacon Race Walk This is an abridged version of walk 5, taken from the ‘Pictorial Guide to the Malvern Hills’ Book Two: Great Malvern. This walk seeks to avoid where ever possible very steep slopes and steps. However, this is a walk on the Malvern Hills and this means there is no avoiding some fairly tough sections along the walk. Copies of the book are available from the Tourist Information Centre, Malvern Book Co- operative, Malvern Gallery, Malvern Museum and Malvern Priory. Priced £8.50 This 5 mile circular walk mostly follows the route of the Worcestershire Beacon Race and provides an interesting, if strenuous, route from Rose Bank Gardens via St Ann’s Well, past the Goldmine and up to the summit of the Worcestershire Beacon. After soaking up the incredible panorama of the Herefordshire and Worcestershire countryside the return journey circumnavigates North Hill before returning to Great Malvern. Allow a whole morning or afternoon for this scenic walk, or if enjoying refuelling stops probably 5 hours is nearer the mark. Turn right out of the Abbey hotel passing through the Priory Gatehouse and as the Post Office is reached, take the sharp left up to the Wells Road with Belle Vue Terrace to the right. Taking care at this junction of the busy Wells Road cross-over to the entrance of Rose Bank Gardens with Malvern’s newest sculpture the eye catching ‘Buzzards’. Belle Vue Terrace Shops 1 The Worcestershire Beacon Race Short Walk Every year since 1953, on the second Saturday in October, Malvern’s most popular running event, the Worcestershire Beacon Race takes place from the Rose Bank Gardens next to the Mount Pleasant Hotel (Map Reference SO 7746 4577). -

Great Malvern Circular Or from Colwall)

The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular) The Malvern Hills (Colwall to Great Malvern) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 20th July 2019 21st July 2019 Current status Document last updated Monday, 22nd July 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. The Malvern Hills (Great Malvern Circular or from Colwall) Start: Great Malvern Station or Colwall Station Finish: Great Malvern Station Great Malvern station, map reference SO 783 457, is 11 km south west of Worcester, 165 km north west of Charing Cross, 84m above sea level and in Worcestershire. Colwall station, map reference SO 756 424, is 4 km south west of Great Malvern, 25 km east of Hereford, 129m above sea level and in Herefordshire. -

Daimler One-O-Four DF310 Overview

Daimler One-O-Four DF310 Overview Origins of the name Daimler Confusingly, the name Daimler is used by two completely separate groups of car manufacturers. The history of both companies can be traced back to the German engineer Gottlieb Daimler who built the first cars in 1889. This was the origin of the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft, which is translated as Daimler Motor Company, which has manufactured vehicles since the 1890s. Gottlieb Daimler died in 1900, having sold licences to use the Daimler name in a number of countries. The licence granted in 1891 to the British F. R. Simms & Co included the right to use the Daimler name in Great Britain and in 1896 the British Daimler Motor Company was founded. History of the Daimler Motor Company (GB) The Daimler Motor Company Limited, was an independent In the 1950s, Daimler stopped making Lanchesters, and tried British motor vehicle manufacturer founded in London by H. to widen its appeal with a line of new developed sport cars J. Lawson in 1896, which set up its manufacturing base in and high-performance luxury limousines. Their chairman, Sir Coventry. The company bought the right to the use of the Bernard Docker and his newly married wife Norah Collins Daimler name simultaneously from Gottlieb Daimler and performed highly publicised extravagances. This led to the Daimler Motoren Gesellschaft of Cannstatt, Germany. After fact that the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth II, who had a early financial difficulty and a reorganization of the company preference for Rolls-Royce anyway, did not use Daimler for in 1904, the Daimler Motor Company was purchased by official events since 1955.