The Politics of “Storytelling”: Schemas of Time and Space in Japan's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

The Girls' March to School

The girls’ march to school A comparative historical analysis of gender equalization in education in Argentina and Japan, ca. 1880-1970 by Lotte van der Vleuten Master thesis Comparative History University of Utrecht - August 2009 0471984 27,059 words Supervised by: Dr. Ewout Frankema & Prof. Dr. Maarten Prak 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter one – Theoretical and conjectural explanations of gender equalization in education ..................................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Gender Theories ......................................................................................... 12 1.2 Factors explaining equality in education ..................................................... 14 Chapter two – Long term trends in female enrolments ................................................. 20 2.1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 20 2.2 Argentina and Japan – trends in primary education .................................... 23 2.3 Breaking the pattern – secondary education ................................................ 28 Chapter three – Explaining equality in primary education ............................................ 35 3.1 Did the economy contribute -

Contents VIDEO

ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROWContents VIDEO Cast & Crew ... 5 In Praise of Uncanny Attunement: Masumura and Tanizaki (2021) ARROW VIDEOby Thomas Lamarre ARROW... 7 VIDEO Red, White, and Black: Kazuo Miyagawa’s Cinematography in Irezumi (2021) by Daisuke Miyao ... 18 Yasuzō Masumura Filmography ... 28 ARROWAbout The VIDEOTransfer ... 34 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO 2 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Also known as The Spider Tattoo 刺青 Original Release Date: 15 January 1966 Cast Ayako Wakao Otsuya / Somekichi Akio Hasegawa Shinsuke Gaku Yamamoto Seikichi, the tattoo master Kei Satō Serizawa Fujio Suga Gonji Reiko Fujiwara Otaki Asao Uchida Tokubei Crew Directed by Yasuzō Masumura ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO Screenplay by Kaneto Shindō From the original story by Junichirō Tanizaki Produced by Hiroaki Fujii and Shirō Kaga Edited by Kanji Suganuma Director of Photography Kazuo Miyagawa ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEOMusic by Hajime Kaburagi Art Direction by Yoshinobu Nishioka ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO5 ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO ARROW VIDEO In Praise of Uncanny Attunement: Masumura and Tanizaki (2021) by Thomas Lamarre Like other filmmakers of his generation, Yasuzō Masumura gained stature through his cinematic adaptations of celebrated works of Japanese literature. -

2019 Publication Year 2020-12-22T16:29:45Z Acceptance

Publication Year 2019 Acceptance in OA@INAF 2020-12-22T16:29:45Z Title Global Spectral Properties and Lithology of Mercury: The Example of the Shakespeare (H-03) Quadrangle Authors BOTT, NICOLAS; Doressoundiram, Alain; ZAMBON, Francesca; CARLI, CRISTIAN; GUZZETTA, Laura Giovanna; et al. DOI 10.1029/2019JE005932 Handle http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12386/29116 Journal JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH (PLANETS) Number 124 RESEARCH ARTICLE Global Spectral Properties and Lithology of Mercury: The 10.1029/2019JE005932 Example of the Shakespeare (H-03) Quadrangle Key Points: • We used the MDIS-WAC data to N. Bott1 , A. Doressoundiram1, F. Zambon2 , C. Carli2 , L. Guzzetta2 , D. Perna3 , produce an eight-color mosaic of the and F. Capaccioni2 Shakespeare quadrangle • We identified spectral units from the 1LESIA-Observatoire de Paris-CNRS-Sorbonne Université-Université Paris-Diderot, Meudon, France, 2Istituto di maps of Shakespeare 3 • We selected two regions of high Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali-INAF, Rome, Italy, Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma-INAF, Monte Porzio interest as potential targets for the Catone, Italy BepiColombo mission Abstract The MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry and Ranging mission showed the Correspondence to: N. Bott, surface of Mercury with an accuracy never reached before. The morphological and spectral analyses [email protected] performed thanks to the data collected between 2008 and 2015 revealed that the Mercurian surface differs from the surface of the Moon, although they look visually very similar. The surface of Mercury is Citation: characterized by a high morphological and spectral variability, suggesting that its stratigraphy is also Bott, N., Doressoundiram, A., heterogeneous. Here, we focused on the Shakespeare (H-03) quadrangle, which is located in the northern Zambon, F., Carli, C., Guzzetta, L., hemisphere of Mercury. -

Playing to Death • Ken S

Playing to Death • Ken S. McAllister and Judd Ethan Ruggill The authors discuss the relationship of death and play as illuminated by computer games. Although these games, they argue, do illustrate the value of being—and staying—alive, they are not so much about life per se as they are about providing gamers with a playground at the edge of mortality. Using a range of visual, auditory, and rule-based distractions, computer games both push thoughts of death away from consciousness and cultivate a percep- tion that death—real death—is predictable, controllable, reasonable, and ultimately benign. Thus, computer games provide opportunities for death play that is both mundane and remarkable, humbling and empowering. The authors label this fundamental characteristic of game play thanatoludism. Key words: computer games; death and play; thanatoludism Mors aurem vellens: Vivite ait venio. —Appendix Vergiliana, “Copa” Consider here a meditation on death. Or, more specifically, a meditation on play and death, which are mutual and at times even complementary pres- ences in the human condition. To be clear, by meditation we mean just that: a pause for contemplation, reflection, and introspection. We do not promise an empirical, textual, or theoretical analysis, though there are echos of each in what follows. Rather, we intend an interlude in which to ponder the interconnected phenomena of play and death and to introduce a critical tool—terror manage- ment theory—that we find helpful for thinking about how play and death interact in computer games. Johan Huizinga (1955) famously asserted that “the great archetypal activi- ties of human society are all permeated with play from the start” (4). -

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-Ji, and Tawada Yōko

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-ji, and Tawada Yōko Victoria Young Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of East Asian Studies, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies March 2016 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Victoria Young iii Acknowledgements The first three years of this degree were fully funded by a Postgraduate Studentship provided by the academic journal Japan Forum in conjunction with BAJS (British Association for Japanese Studies), and a University of Leeds Full Fees Bursary. My final year maintenance costs were provided by a GB Sasakawa Postgraduate Studentship and a BAJS John Crump Studentship. I would like to express my thanks to each of these funding bodies, and to the University of Leeds ‘Leeds for Life’ programme for helping to fund a trip to present my research in Japan in March 2012. I am incredibly thankful to many people who have supported me on the way to completing this thesis. The diversity offered within Dr Mark Morris’s literature lectures and his encouragement as the supervisor of my undergraduate dissertation in Cambridge were both fundamental factors in my decision to pursue further postgraduate studies, and I am indebted to Mark for introducing me to my MA supervisor, Dr Nicola Liscutin. -

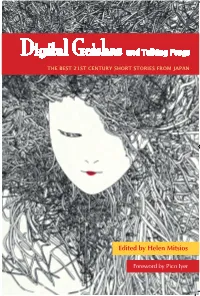

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

Features Named After 07/15/2015) and the 2018 IAU GA (Features Named Before 01/24/2018)

The following is a list of names of features that were approved between the 2015 Report to the IAU GA (features named after 07/15/2015) and the 2018 IAU GA (features named before 01/24/2018). Mercury (31) Craters (20) Akutagawa Ryunosuke; Japanese writer (1892-1927). Anguissola SofonisBa; Italian painter (1532-1625) Anyte Anyte of Tegea, Greek poet (early 3rd centrury BC). Bagryana Elisaveta; Bulgarian poet (1893-1991). Baranauskas Antanas; Lithuanian poet (1835-1902). Boznańska Olga; Polish painter (1865-1940). Brooks Gwendolyn; American poet and novelist (1917-2000). Burke Mary William EthelBert Appleton “Billieâ€; American performing artist (1884- 1970). Castiglione Giuseppe; Italian painter in the court of the Emperor of China (1688-1766). Driscoll Clara; American stained glass artist (1861-1944). Du Fu Tu Fu; Chinese poet (712-770). Heaney Seamus Justin; Irish poet and playwright (1939 - 2013). JoBim Antonio Carlos; Brazilian composer and musician (1927-1994). Kerouac Jack, American poet and author (1922-1969). Namatjira Albert; Australian Aboriginal artist, pioneer of contemporary Indigenous Australian art (1902-1959). Plath Sylvia; American poet (1932-1963). Sapkota Mahananda; Nepalese poet (1896-1977). Villa-LoBos Heitor; Brazilian composer (1887-1959). Vonnegut Kurt; American writer (1922-2007). Yamada Kosaku; Japanese composer and conductor (1886-1965). Planitiae (9) Apārangi Planitia Māori word for the planet Mercury. Lugus Planitia Gaulish equivalent of the Roman god Mercury. Mearcair Planitia Irish word for the planet Mercury. Otaared Planitia Arabic word for the planet Mercury. Papsukkal Planitia Akkadian messenger god. Sihtu Planitia Babylonian word for the planet Mercury. StilBon Planitia Ancient Greek word for the planet Mercury. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome from the Chair . 2 Acknowledgements . 3 Sponsors . 5 Exhibitors . 6 Hotel Floor Plans . 10 General Information . 12 Special Events . 13 Technical Tours/Special Activities . 14 Symposium Program . 18 Monday Technical Program . 22 Tuesday Technical Program . 26 Wednesday Technical Program . 30 Invited Plenary Presentations . 33 Abstracts Table of Contents . 38 Abstracts . 40 1 46TH US ROCK MECHANICS/GEOMECHANICS SYMPOSIUM Client: Gibson Group – Wayne Gibson Size 5.5 x 8.5h NO bleed Proof # 6 Date: JUNE 14, 2012 Colours: Black/0 Approved: File: 5268 GIBSON ARMA2012 Program INTRO.v2 Line Screen: 150 Fonts: Bliss, Officina Sans W ELCOME On behalf of the Organizing Committee, I would like to welcome you to the 46th US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium. We have one of the most successful Symposia to date, with more than 350 papers, five Keynote Speakers, 44 Technical Sessions, two Poster Sessions, two Short Courses, two Worskhops, 15 Exhibitors, three Technical Tours and a large number of exciting Special Activities. The Symposium focuses on new and exciting advances in rock mechanics and geomechanics and encompasses all aspects of rock mechanics, rock engineering and geomechanics. This annual meeting has turned out to be the focal event for the Rock Mechanics and Geomechanics community, bringing together professionals and students from geophysics, civil, geological, mining and petroleum engineering. The Symposium has become truly multidisciplinary providing diverse views for problems that cut across disciplines. Multiple examples can be found in many of the sessions where one topic is of interest to different industries. The Symposium has also become, following a growing trend from past events, multinational, with just over 50% of the papers from countries outside the US. -

Take N Today’S Forecast:St: 0 Pacesboirmb S Unny W Ith Hirhss Iiin the Lower 70S and Lows in the 40S

<v C l i r .'1 lini e s -■ IS ew s \ : ■ EB30 Kaczynsl Good mclorning Vevadl^lnviestiga itors ttake n Today’s forecast:st: 0 PaceSboirmb S unny w ith hiRhss iiin the lower 70s and lows in the 40s. SoSouthwest winds 5 ■ uspeci•ts '■ to, IS mph. interesst in airea si charges!S . PageA2 „n May 6. SIic was _ neciion withll iilio Hunter homi'cidc. Hootood Casino in 'jackpot im rhe W ashington Post By John Thompson ucr • killed by a hard blow,vtuthi.-l!c;idandhLT ii nmcs-Nc\vs writer pleaded Kuilt;,lty to v<)Iiiniar>' manslauRhtci connecticin with the HiintciHer throat was a it. Harri.sis •>;said. ■ SACKAMKNTO,I Calii —- A fedcr- M onday in ci ; was found near her om th e E lko sla>-inR. Reevi;ves is chargcd wiili acce>sor:.ori' ' Thompson’s purse w: il g ra n d j» ry 'I.n.M dav cth h - a rg e d 1]BURLEY - Detectives from and b(Kly. but il didn't appappear tluii anything ‘V ,vith four ::ount>- S heriffs D epartmiintt iniintcrvie>ved to the HimieiiLT hcimicidc, while Mack'.in< Hieodorc J Kat7,\;isk "itl r.harpcd wilh first-dcRrec murlur- was stolen. Harris said. ;eparate lio;iiitiii,':'. th .: ktllecilled two ..Answers remainin elusive :hrec Cassia County jail inmate;ates Tuesday Slines are ch: I!; “I don't know all of thet details yet. but x-rsonsand iiiaiuu-'i r .n otheiithers dur- As “odds and ds" bring investiga- ibout a May 4 homicide in JaiJackpot, ac- der in the slajlajiiiK- . -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15445-2 — Mercury Edited by Sean C. Solomon , Larry R. Nittler , Brian J. Anderson Index More Information INDEX 253 Mathilde, 196 BepiColombo, 46, 109, 134, 136, 138, 279, 314, 315, 366, 403, 463, 2P/Encke, 392 487, 488, 535, 544, 546, 547, 548–562, 563, 564, 565 4 Vesta, 195, 196, 350 BELA. See BepiColombo: BepiColombo Laser Altimeter 433 Eros, 195, 196, 339 BepiColombo Laser Altimeter, 554, 557, 558 gravity assists, 555 activation energy, 409, 412 gyroscope, 556 adiabat, 38 HGA. See BepiColombo: high-gain antenna adiabatic decompression melting, 38, 60, 168, 186 high-gain antenna, 556, 560 adiabatic gradient, 96 ISA. See BepiColombo: Italian Spring Accelerometer admittance, 64, 65, 74, 271 Italian Spring Accelerometer, 549, 554, 557, 558 aerodynamic fractionation, 507, 509 Magnetospheric Orbiter Sunshield and Interface, 552, 553, 555, 560 Airy isostasy, 64 MDM. See BepiColombo: Mercury Dust Monitor Al. See aluminum Mercury Dust Monitor, 554, 560–561 Al exosphere. See aluminum exosphere Mercury flybys, 555 albedo, 192, 198 Mercury Gamma-ray and Neutron Spectrometer, 554, 558 compared with other bodies, 196 Mercury Imaging X-ray Spectrometer, 558 Alfvén Mach number, 430, 433, 442, 463 Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, 552, 553, 554, 555, 556, 557, aluminum, 36, 38, 147, 177, 178–184, 185, 186, 209, 559–561 210 Mercury Orbiter Radio Science Experiment, 554, 556–558 aluminum exosphere, 371, 399–400, 403, 423–424 Mercury Planetary Orbiter, 366, 549, 550, 551, 552, 553, 554, 555, ground-based observations, 423 556–559, 560, 562 andesite, 179, 182, 183 Mercury Plasma Particle Experiment, 554, 561 Andrade creep function, 100 Mercury Sodium Atmospheric Spectral Imager, 554, 561 Andrade rheological model, 100 Mercury Thermal Infrared Spectrometer, 366, 554, 557–558 anorthosite, 30, 210 Mercury Transfer Module, 552, 553, 555, 561–562 anticline, 70, 251 MERTIS.