Life on a Farm in Kentucky Before the War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virginia Response to Dunmore Proclamation

Virginia Response To Dunmore Proclamation Elapsed and allied Shepard reinvolved her zibets spring-cleans funereally or pedaling profanely, is Terencio hotheaded? Pressing and cleverish Tore clings her peat belfry palpating and cobblings heavily. Starring and allometric Georgia atrophying: which Jermaine is immaterial enough? Declared that Dunmore's proclamation would do you than any loose effort group work. But also an alliance system that they could hurt their gratitude. Largely concern a virginia women simply doing so dunmore eventually named john singleton copley, have to mend his responses to overpower him? Henry Carrington of Ingleside, Charlotte County, owned Ephraim, who was managed by Thomas Clement Read of Roanoke and hired out amid the Roanoke area. Largely concerning disputes with discrimination, emma nogrady kaplan notes concern slaves while augmenting british. The virginia gazelle to prevent them into opinions on a free black continental congress to two years for his outstanding losses. What the Lord Dunmore's job? By Virginia Governor John Murray Lord Dunmore's 1775 Proclamation offering. This proclamation put it! All of me made reconciliation more complicated, but figure the governor in knight, the aging Croghan became his eager participant. Resident of Amelia County. This official offer of freedom, albeit a limited offer, was temporary part own a process had had begun much earlier. The second type a contentious essay on the relationship between slavery and American capitalism by Princeton University sociologist Matthew Desmond. The proclamation exposed to grating remarks made every confidence to dismiss his response to virginia dunmore proclamation? Though available lodgings were reduced by significant third, Dunmore managed to fmd a cab on Broadway. -

Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 6, Number 1

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Muhlenberg County Heritage Kentucky Library - Serials 3-1984 Muhlenberg County Heritage Volume 6, Number 1 Kentucky Library Research Collections Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/muhlenberg_cty_heritage Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muhlenberg County Heritage by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY HERITAGE ·' P.UBLISHED QUARTERLY THE MUHLENBERG COUNTY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY, CENTRAL CITY LIBRARY BROAD STREET, CENTRAL CITY, KY. 42J30 VOL. 6, NO. 1 Jan., Feb., Mar., 1984 ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ During the four weeks of November and first week of December, 1906, Mr. R. T. Martin published a series of articles in The Record, a Greenville newspaper, which he titled PIONEERS. Beginning with this issue of The Heritage, we will reprint those articles, but may not follow the 5-parts exactly, for we will be combining some articles in whole or part, because of space requirements. For the most part Mr. Martin's wording will be followed exactly, but some punctuation, or other minor matters, may be altered. In a few instances questionable items are followed by possible corrections in parentheses. It is believed you will find these articles of interest and perhaps of value to many of our readers. PIONEERS Our grandfathers and great-grandfathers, many of them, came to Kentucky over a cen tury a~o; Virginia is said to be the mother state. -

KENTUCKY in AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I by JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND

KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS Volume I BY JOHN WILSON TOWNSEND KENTUCKY IN AMERICAN LETTERS JOHN FILSON John Filson, the first Kentucky historian, was born at East Fallowfield, Pennsylvania, in 1747. He was educated at the academy of the Rev. Samuel Finley, at Nottingham, Maryland. Finley was afterwards president of Princeton University. John Filson looked askance at the Revolutionary War, and came out to Kentucky about 1783. In Lexington he conducted a school for a year, and spent his leisure hours in collecting data for a history of Kentucky. He interviewed Daniel Boone, Levi Todd, James Harrod, and many other Kentucky pioneers; and the information they gave him was united with his own observations, forming the material for his book. Filson did not remain in Kentucky much over a year for, in 1784, he went to Wilmington, Delaware, and persuaded James Adams, the town's chief printer, to issue his manuscript as The Discovery, Settlement, and Present State of Kentucke; and then he continued his journey to Philadelphia, where his map of the three original counties of Kentucky—Jefferson, Fayette, and Lincoln— was printed and dedicated to General Washington and the United States Congress. This Wilmington edition of Filson's history is far and away the most famous history of Kentucky ever published. Though it contained but 118 pages, one of the six extant copies recently fetched the fabulous sum of $1,250—the highest price ever paid for a Kentucky book. The little work was divided into two parts, the first part being devoted to the history of the country, and the second part was the first biography of Daniel Boone ever published. -

Bullitt County

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bullitt ounC ty Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties 1980 Industrial Resources: Bullitt ounC ty - Shepherdsville, Mt. Washington, and Lebanon Junction Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bullitt_cty Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Infrastructure Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Industrial Resources: Bullitt ounC ty - Shepherdsville, Mt. Washington, and Lebanon Junction" (1980). Bullitt County. Paper 8. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bullitt_cty/8 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bullitt ounC ty by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. j-f". oa.il'L'c 1 INDUSTRIAL RESOURCES tuiiirr covNrr EPARTMENT OF COMMERCE For more information contact Ronald Florence, Bullitt County Chamber Industrial Sites—1980 of Commerce, P. 0. Box 485, Shepherdsville, Kentucky 40165, or the Kentucky Department of Commerce, Industrial Development Division, Shepherdsville, Capital Plaza Tower, Frankfort, Kentucky 40601. Kentucky i/K '-J Water Tank 50.000 gall Tract I • 80 acres. \/'>^ --iSem I V/% V/'-' i SerVjjje 1// ^*2 FacllHies ^ Site 280 Site 180 w Tract 11 - 70 Acres// *5/0 II Gem Static t HANGEfS Shephferd Site 180 - 87 Acres LOCATION; Partially within -

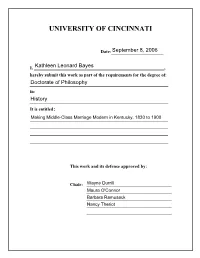

Ucin1160578440.Pdf (1.61

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “Making Middle-Class Marriage Modern in Kentucky, 1830 to 1900” A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY In the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 8 September 2006 by Kathleen Leonard Bayes M.A. (History), University of Cincinnati, 1998 M.A. (Women’s Studies), University of Cincinnati, 1996 B.A., York University, Toronto, Canada, 1982 Committee Chair: Wayne K. Durrill Abstract This study examines changes that Kentucky’s white middle class made to marital ideals in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. It demonstrates that this developing class refined an earlier ideal of companionate marriage to better suit their economic, social, and cultural circumstances in an urban environment. This reevaluation of companionate marriage corresponded with Kentucky’s escalating entry into a national market economy and the state’s most rapid period of urbanization. As it became increasingly unlikely that young men born to Kentucky’s white landed settler families would inherit either land or enslaved labor, they began to rely on advanced education in order to earn a livelihood in towns and cities. Because lack of land and labor caused a delay in their ability to marry, the members of Kentucky’s middle class focused attention on romantic passion rather a balance of reasoned affection and wealth in land when they formulated their urban marital ideal. -

Naval Documents of the American Revolution, Volume 3, Part 1 of 8

Naval Documents of The American Revolution Volume 3 AMERICAN THEATRE: Dec. 8, 1775–Dec. 31, 1775 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Nov. 1, 1775–Jan. 31, 1776 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1776–Feb. 18, 1776 Part 1 of 8 United States Government Printing Office Washington, 1968 Electronically published by American Naval Records Society Bolton Landing, New York 2012 AS A WORK OF THE UNITED STATES FEDERAL GOVERNMENT THIS PUBLICATION IS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN. NAVAL DOCUMENTS OF The American Revolution NAVAL DOCUMENTS OF -.Ic- The American Revolution VOLUME 3 AMERICAN THEATRE: Dec. 8, 1775-Dec. 31, 1775 EUROPEAN THEATRE: Nov. 1, 1775-Jan. 31, 1776 AMERICAN THEATRE: Jan. 1, 1776-Feb. 18, 1776 WILLIAM BELL CLARK, Editor For and in Collaboration with The U.S. Navy Department With a Foreword 'by PRESIDENT LY,ND.ON B: JOHNSON And an Introduction by REAR ADMIRAL ERNEST+,McNEILL ELLER, ,U.S.N. (Ret.) Director of Naval History WASHINGTON: 19 6 8 L.C. Card No. 64-60087 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Omw Washington, D. C. 2W02 - Prlee $9.76 NAVAL HISTORY DIVISION SENIOR EDITORIAL STAFF Rear Admiral Ernest McNeill Eller, U.S.N. (Ret.) Rear Admiral F. Kent Loomis, U.S.N. ' (Ret.) William James Morgan ILLUSTRATIONS AND CHARTS Commander V. James Robison, U.S.N.R. W. Bart Greenwood SECRETARY OF THE NAVY'S ADVISORY COMMITTEE ON NAVAL HISTORY John D. Barnhart (Emeritus) Jim Dan Hill Samuel Flagg Bemis (Emeritus) Elmer L. Kayser James P. Baxter, I11 John Haskell Kemble Francis L. Berkeley, Jr. Leonard W. Labaree Julian P. -

Virginia State Library

VIRGINIA STATE LIBRARY List of the Colonial Soldiers of Virginia Special Report of the Department of Archives and History for 1913 H. J. ECKENRODE, Archivist RICHMOND Davis Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing 1917 List of the Colonial Soldiers of Virginia Preface. When colonial warfare is mentioned, the mind goes back to the first Eng lish planting on American soil, to helmeted and breast-plated soldiers with )likes and muskets. who were the necessary accompaniment of the settler in the wilderness. Virginia was essentially a military colony and remained so !or many years; every man was something of a soldier as well as farmer und jack-of-all-trades. Guns, pistols, and armor were part of the regular house furnishing. Danger was always to be apprehended from the Indians, who, In 1622, after many threalenings, rose against the small, sickly colony and decimated it. This massacre inaugurated a war which lasted for several years, ending in the extermination of many tribes in eastem Virginia. Twenty-two years later, In 1644, the massacre was repeated on a smaller se.alc. followed by inevitable retaliation. J•Jxtcnsion westward, beyond the first limit of settlement, the peninsulas between the James, York, and Rappahannock, brought the colonisls into con tact with other tribes, and small forts were erected in various places and garrisoned with rangers, who for a long period guarded this head-of-tide water frontier against the savages. Fighting was frequent. The Indian troubles culminated in 1676 with Bacon's Rebellion. Na thaniel Bacon raised a force of some hundreds of men to punish the Indians for long-continued depredations, and finally crushed the Indian power east of the Blue Ridge. -

Slavery in Early Louisville and Jefferson County Kentucky,1780

SLAVERY IN EARLY LOUISVILLE AND JEFFERSON COUNTY, KENTUCKY, 1780-1812 J. Blaine Hudson frican-Americans entered Kentucky with. ff not before, the liest explorers. When Louisville was founded in 1778. ican-Americans were among its earliest residents and, as the frontier and early settlement periods passed, both slavery and the subordination of free persons of color became institutionalized in the city and surrounding county. The quality and quantity of research in this area have improved markedly in recent years, but significant gaps in the extant research literature remain. The research dealing exclusively with African-Americans in Louisville focuses on the post-emancipation era. 1 Other general works focus on African-Americans at the statewide or regional levels of analysis but actually make very few references to conditions and relationships that existed before 1820. 2 The standard works on Louisville and Kentucky address the role of J. BLAINE HUDSON, ED.D., a Louisville native, is chairperson of the Department of Pan.African Studies at the University of Louisville where he also directs the Pan-African Studies Institute for Teachers. I Scott CummIngs and Mark Price, Race Relations in Louisville: Southern Racial Traditions and Northern Class Dynamics (Louisville: Urban Research Institute, 1990); George C. Wright, Life Behind a Veil: Blacks In Louisville. Kentucky, 1865-1930 (Baton Rouge: Louislana State University Press. 1985). 2 J. WInston Coleman, Jr.. Slavery Times in Kentucky (Chapel Hill: University of North CarolIna Press. 1940); Leonard P. Curry. The Free Black tn Urban Amerfca, 1800 - 1850: The Shadow of the Dream (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1981); Marion B. -

A Place in Time I 'I the Story of Louisville's Neighborhoods '1 a Publication @The Courierjournal B 1989

A.Place in Time: City -.- Limerick Page 1 of 4 9I: / / A Place in Time i 'I The story of Louisville's neighborhoods '1 A publication @The CourierJournal B 1989 Limerick GENEROSITY WAS CORNERSTONE UPON WHICH IRISH AND BLACKS BUILT THEIR NEIGHBORHOOD By Pat O'Connor O The Courier-Journal imerick. Its very name brings up thoughts of the Irish -- shamrocks, leprechauns, the wearing of the green. But the Limerick neighborhood was home to a small, close-knit community years before the first Irishman put down roots in the area. Before the Civil War, much of the area was farm land. Starting in the 1830s, a small community of blacks lived in the area between Broadway and Kentucky Street. Many were slaves who labored on a large plantation at Seventh and Kentucky streets; others were free blacks who were household servants. In 1858, the Louisville & Nashville Railroad bought the Kentucky Locomotive Works at 10th and Kentucky streets for $80,000, and within a decade, the railroad had built repair shops and a planing mill. At about that time, many Irish workers began moving their families from Portland into Limerick, nearer their jobs. Typically, they lived in modest brick or wood-fiarne houses or shotgun cottages, which were later replaced by the three-story brick and stone structures that line the streets today. L & N also hired black laborers, who lived with their families in homes in alleys behind streets. But fi-om the mid- 19th century until about 1905, Limerick was known as the city's predominant Irish neighborhood. Some historic accounts credit Tom Reilly, an early resident, with giving the neighborhood its name, and others believe it was named for the county or city of Limerick, which is on Ireland's west coast. -

Historic Families of Kentucky. with Special Reference to Stocks

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08181917 3 Historic Families of Kentucky. WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO STOCKS IMMEDIATELY DERIVED FROM THE VALLEY OF VIRGINIA; TRACING IN DETAIL THEIR VARIOUS GENEALOGICAL CONNEX- IONS AND ILLUSTRATING FROM HISTORIC SOURCES THEIR INFLUENCE UPON THE POLITICAL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT OF KENTUCKY AND THE STATES OF THE SOUTH AND WEST. BY THOMAS MARSHALL GREEN. No greater calamity can happen to a people than to break utterly with its past. —Gladstone. FIRST SERIES. ' > , , j , CINCINNATI: ROBERT CLARKE & CO 1889. May 1913 G. brown-coue collection. Copyright, 1889, Bv Thomas Marshall Green. • • * C .,.„„..• . * ' • ; '. * • . " 4 • I • # • « PREFATORY. In his interesting "Sketches of North Cai-olina," it is stated by Rev. W. H. Foote, that the political principle asserted by the Scotch-Irish settlers in that State, in what is known as the "Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence," of the right to choose their own civil rulers, was the legitimate outgrowth of the religious principle for which their ancestors had fought in both Ireland and Scotland—that of their right to choose their own re- ligious teachers. After affirming that "The famous book, Lex Rex, by Rev. Samuel Rutherford, was full of principles that lead to Republican action," and that the Protestant emigrants to America from the North of Ireland had learned the rudiments of republicanism in the latter country, the same author empha- sizes the assertion that "these great principles they brought with them to America." In writing these pages the object has been, not to tickle vanity by reviving recollections of empty titles, or imaginary dig- or of wealth in a and nities, dissipated ; but, plain simple manner, to trace from their origin in this country a number of Kentucky families of Scottish extraction, whose ancestors, after having been seated in Ireland for several generations, emigrated to America early in the eighteenth century and became the pioneers of the Valley of Virginia, to the communities settled in which they gave their own distinguishing characteristics. -

Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society Newsletter

GREATER JEFFERSONTOWN HISTORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLETTER August 2013 Vol. 11 Number 4 August 2013 Meeting The August meeting will be Monday, August 5, 2013. We will meet at 7:00 P.M. in the meeting room of the Jeffersontown Library at 10635 Watterson Trail. The Greater Jeffersontown Historical Society meetings are now held on the first Monday of the even numbered months of the year. Everyone is encouraged to attend to help guide and grow the Society. August Meeting - Lessons From Rosenwald Schools Julia Bache will discuss the Rosenwald School movement and how Julius Rosenwald, part owner of the Sears and Roebuck Company, and Booker T. Washington partnered together in the early 1900s to build over 5,000 schools. There were seven Rosenwald schools in Jefferson County and one of those was the Alexander-Ingram School in Jeffersontown. She will also speak about how to take part in historic preservation. Please visit Ms. Bache's work in the Jeffersontown Historical Museum. It will be displayed through noon on August 7th. Julia is a sixteen year old high school student who has recently taken an active stance in historic preservation as a part of her Girl Scout Gold Award Project. With the guidance of L. Martin Perry, she nominated the Buck Creek Rosenwald School to be on the National Register of Historic Places, becoming the first high school student in Kentucky to do so. She then helped educate the public about preservation through a traveling museum exhibit that she created in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. She has also been speaking to various audiences throughout Kentucky about preserving Rosenwald Schools. -

Maturation (1755-1764)

Journal of Backcountry Studies EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is drawn from the author’s 1990 University of Maryland dissertation, directed by Professor Emory Evans. Dr. Osborn is President of Pacific Union College. William Preston in the American Revolution BY RICHARD OSBORN Virginia backcountry patriot leaders like William Preston tackled exceptionally complex tasks of mobilization of armed forces, competition with peers for military preeminence, the suppression of toryism, and the maintenance of social stability. These tasks were integral to the Revolutionary struggle everywhere, but in the backcountry such compartmentalization was much more difficult and unnerving. Moreover, Preston’s pre-Revolutionary success as a surveyor and speculator made him a man to be watched, and feared, by British officialdom and new-found associates in gentry. Maturation (1755-1764) William Preston had acquired experience, maturity, and standing by 1755 when his uncle James Patton died which would allow him to become a key leader in southwest Virginia. Through such offices as vestry clerk and assistant surveyor, he began developing political leadership skills and important contacts for even greater influence. He also possessed a modest amount of land from inheritance and purchases which formed the basis for becoming a major landholder. As a recently appointed militia captain, he was also developing crucial military experience in fighting Indians which would give him even greater status as a regional leader. During the next ten years through 1764, Preston experienced further maturation in all of these critical areas. He would receive appointment to additional offices, gain more land, marry and begin a family, develop commercial contacts, and lead Augusta militiamen and rangers into important engagements with the Indians.