Against the Immigrant, for the Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Statement OMB NO

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 06/05/2012 11:27:24 AM U.S. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement OMB NO. 1124-0002 Washington, DC 20530 Pursuant to Section 2 ofthe Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending April 30, 2012 ; (Insert date) I - REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Nelson Mullins Riley & Scarborough LLP 5928 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 1320 Main Street, 17th Floor, Columbia, SC 29201 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No Ex] (2) Citizenship Yes • No [3 (3) Occupation Yes • No [x] (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes • No H (2) Ownership or control Yes • No 0 (3) Branch offices Yes • No [3 (c) Explain fully all changes, if any, indicated in items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4 AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C', state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes D No S If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? Yes • No • If no, please attach the required amendment. i The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver of the requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

Newly Elected Senators and Representatives Senate Sheila Mcneill

Welcome! Newly Elected Senators and Representatives Senate Sheila McNeill District 3 Billy Hickman District 4 Russ Goodman District 8 Nikki Merritt District 9 Carden Summers District 13 Max Burns District 23 Jason Anavitarte District 31 Sonya Halpern District 39 Kim Jackson District 41 Clint Dixon District 45 Michelle Au District 48 Bo Hatchett District 50 House of Representatives Mike Cameron District 1 Matt Barton District 5 Stan Gunter District 8 Will Wade District 9 Victor Anderson District 10 Mitchell Scoggins District 14 Tyler Smith District 18 Charlice Byrd District 20 Brad Thomas District 21 Lauren W. McDonald III District 26 Rob Leverett District 33 Shea Roberts District 52 Mesha Mainor District 56 Stacey Evans District 57 Mandisha Thomas District 65 Philip Singleton District 71 Yasmin Neal District 74 Zulma Lopez District 86 Rhonda Taylor District 91 Marvin Lim District 99 Rebecca Mitchell District 106 Regina Lewis-Ward District 109 Clint Crowe District 110 Sharon Henderson District 113 Beth Camp District 131 David Jenkins District 132 Robert Pruitt District 149 Bill Yearta District 152 Derek Mallow District 163 Buddy DeLoach District 167 Joe Campbell District 171 James Burchett District 176 WAR ON ILLITERACY by Malcolm Mitchell LITERATE: THE BASIC ABILITY TO UNDERSTAND OR PRODUCE WRITTEN INFORMATION. ILLITERATE: THE INABILITY TO UNDERSTAND OR PRODUCE WRITTEN INFORMATION. If a child is not reading proficiently by the 4th grade, they have a 78% chance of not catching up. 90% of welfare recipients are either school dropouts or illiterate. 85% of juveniles who interface with the court system are functionally illiterate. 82% of students eligible for free or reduced lunches cannot read proficiently. -

United for Health PAC 2015 U.S. Political Contributions & Related

2015 US Political Contributions & Related Activity Report LETTER FROM THE CHAIRMAN Our workforce of more than 225,000 people is dedicated to helping people live healthier lives and helping to make the health system work better for everyone. Technological change, new collaborations, market dynamics and a shift toward building a more modern infrastructure for health care are driving rapid evolution of the health care market. Federal and state policy-makers, on behalf of their constituents and communities, continue to be deeply involved in this changing marketplace. UnitedHealth Group remains an active participant in the political process to provide proven solutions that enhance the health system. The United for Health PAC is an important component of our overall strategy to engage with elected officials and policy-makers, to communicate our perspectives on priority issues, and to share with them our capabilities and innovations. The United for Health PAC is a nonpartisan political action committee supported by voluntary contributions from eligible employees. The PAC supports federal and state candidates who align with our business objectives to increase quality, access, and affordability in health care, in accordance with applicable election laws and as overseen by the UnitedHealth Group Board of Directors’ Public Policy Strategies and Responsibility Committee. UnitedHealth Group remains committed to sharing with federal and state governments the advances and expertise we have developed to improve the nation’s overall health and well-being. -

GSRA's Legislative

Georgia State Retirees Association Communicating Our Goals to Legislators A Tool Kit Adopted November 2015 2016 GSRA Key Legislative Issues Support for a 3% across the board pay increase for all active state employees. Salaries have remained low for active state employees since 2008 and benefit costs have increased. Turnover among active employees has reached the 35-45% level making the delivery of services difficult and requiring constant re-training. These employees are Georgia’s future. Cost of Living Adjustment (COLA) for ERS Retirees The median income for all ERS retirees is only $21,750.00 a year with more than 60% of ERS retirees receiving less than $28,000.00. These retired public servants have not had a COLA in eight years, unlike many other retirees in our state. GSRA urges that a COLA of some amount, as funds are identified, be provided to ERS retirees to help restore the lost purchasing power due to inflation on these employees' fixed-benefit pensions over the past eight years. State Health Benefit Plan (SHBP) Transparency GSRA and other retiree organizations support legislation to provide transparency in the SHBP plan design and changes. Such legislation was introduced in both the 2014 and 2015 Sessions, and would include the addition of an advisory council to the DCH composed of education and general employee retirees. This would allow proposed plan modifications to be discussed and deliberated prior to adoption by DCH. GSRA urges that this legislation be passed and signed by the Governor. Changes in State Policy Regarding Health Benefits GSRA recognizes that the increasing cost of health benefits is a big state budget item, but urges recognition by state decision-makers that health benefits are a component of public employees' total benefits packages. -

The RISE and REACH of Surveillance Technology 2

21st Century Policing: The RISE and REACH of Surveillance Technology 2 About the Authors Action Center on Race and The Community Resource the Economy (ACRE) Hub for Safety and The Action Center on Race and the Economy Accountability (ACRE) is a campaign hub for organizations The Hub serves as a resource for local advocates and working at the intersection of racial justice and Wall organizers working to address the harms of policing in Street accountability. We provide research and the U.S. and seeking to cultivate community safety and communications infrastructure and strategic support accountability outside of the criminal legal system. The for organizations working on campaigns to win Hub is a conduit of information and assistance for local structural change by directly taking on the financial grassroots organizations across this nation and beyond. elite that are responsible for pillaging communities of color, devastating working-class communities, This report was written by Jasson Perez, Alyxandra and harming our environment. We partner with local Goodwin, and Jessica Quiason of ACRE and Kelcey organizations from across the United States that Duggan, Niaz Kasravi, and Philip McHarris of The Hub. are working on racial, economic, environmental, and education justice campaigns and help them connect Special thanks to Kendra Bozarth, Tracey Corder and the dots between their issues and Wall Street, so that Carrie Sloan for your invaluable edits. each of the local efforts feeds into a broad national movement to hold the financial sector accountable. Acknowledgements We want to thank the following people for taking time to speak with us about their work and law enforcement surveillance generally: • Albert Fox Cahn, Esq. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Framing Illegality: Sonic Culture, Power, and the Politics of Representation Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7994f9m4 Author Arellano, Gerardo Nunez Publication Date 2010 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Framing Illegality in the United States: Sonic Culture, Power and the Politics of Representation By Gerardo Nunez Arellano A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor José D. Saldívar, Chair Professor Michael Omi Professor Richard Walker Fall 2010 © 2010 Gerardo Nunez Arellano Abstract Framing Illegality in the United States: Sonic Culture, Power, and the Politics of Representation By Gerardo Nunez Arellano Doctor in Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor José D. Saldívar, Chair This dissertation takes an interdisciplinary approach and situates nation-building, ordinary culture, and racial formation within the context of the immigration debates during the 1980s and 1990s in the United States. Specifically, I argue that the historical and discursive significance of the term illegal alien stems from the ways in which society negotiates and challenges presupposed assumptions, privileges, rewards, and attitudes toward a segment of US society associated with undocumented immigration into the United States. The dissertation demonstrates the crisis the State faced in negotiating, on the one hand, the needs of capital (e.g., the availability of cheap labor) and on the other the social dilemmas of enforcing equitable immigration reform (e.g., the Immigrant Reform and Control Act of 1986 and Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act of 1996). -

Final Remarks to the Board of Governors by Charles L

GBJ Feature Final Remarks to the Board of Governors by Charles L. Ruffin The bylaws of the State Bar of Georgia specify the duties of the president. One of the responsibilities is to “deliver a report at the Annual Meeting of the members of the activities of the State Bar during his or her term in office and furnish a copy of the report to the Supreme Court of Georgia.” Following is the report from 2013-14 President Charles L. Ruffin on his year, delivered June 6, at the State Bar’s Annual Meeting. ood morning. As I have the opportunity to preside over a meeting of the Board G of Governors one final time, I wish to once again express my appreciation for the privilege of serving as the 51st president of the State Bar of Georgia. In fact, that will be the sole focus of my remarks this morning. To those who have worked so hard to make this past year a successful time of historical obser- vance—as we have celebrated not only the 50th anni- versary of the State Bar of Georgia, but the 225th anni- versary of the ratification of the U.S. Constitution—to all who participated this year, I simply want to say “thank you.” The fact of the matter is, the State Bar of Georgia is a huge team made up of many leaders who Photo by Sarah I. Coole in their own geographic area and areas of practice 2013-14 President Charles L. Ruffin addresses the Board of Governors contribute greatly to an orderly system of justice that and others in attendance during the Annual Meeting. -

Political Contributions & Related Activity Report

Political Contributions & Related Activity Report 2010 CARTER BECK JOHN JESSER DAVID KRETSCHMER SVP & Counsel VP, Provider Engagement & COC SVP, Treasurer & Chief Investment Officer ANDREW LANG LISA LATTS SVP, Chief Information Officer Staff VP, Public Health Policy MIKE MELLOH VP, Human Resources DEB MOESSNER ANDREW MORRISON 2010 WellPAC President & General Manager KY SVP, Public Affairs BRIAN SASSI WellPAC Chairman EVP, Strategy & Marketing, Board of Directors BRIAN SWEET President & CEO Consumer VP, Chief Clinical Pharmacy Officer JOHN WILLEY Director, Government Relations TRACY WINN ALAN ALBRIGHT WellPAC Treasurer Manager, Public Affairs Legal Counsel to WellPAC WellPAC Assistant Treasurer & Executive Director 1 from the Chairman Recognizing the impact that public policy decisions have on our stakeholders, WellPoint has made a commitment to be involved in the political process. Our efforts include policy development, direct advocacy, lawful corporate contributions and the sponsorship of WellPAC, the non- partisan political action committee of WellPoint associates. WellPAC’s purpose is to help elect candidates for federal and state office who share our mission of making health care reform work for our customers, our associates, our investors and the communities we serve. WellPoint pays the PAC’s administrative costs as allowed by law, but all WellPAC contributions are funded through the voluntary support of eligible WellPoint associates. In 2010, WellPAC contributed $596,999 to federal candidates, political parties and committees, and $192,581 to candidates and committees at the state and local levels. In total, WellPoint made more than $2.8 million in corporate political contributions. Additionally, our public affairs team actively engaged with lawmakers and candidates at the federal level, and in our 14 core business states. -

House and Senate Leadership — 2015 of the 180 Members of the House of Representatives, Republicans Hold 119 Seats and Democrats Hold 61 Seats

House and Senate Leadership — 2015 Of the 180 members of the House of Representatives, Republicans hold 119 seats and Democrats hold 61 seats. The Senate has 56 members, comprised of 38 Republicans and 18 Democrats. For each chamber, a simple majority vote requires 50% plus 1 vote. That means 91 “yea” votes for passage in the House and 29 “yea” votes for the Senate. Each Chamber requires a 2/3 majority vote to pass a constitutional amendment. That means 120 votes in the House and 38 in the Senate. House Majority Party David Ralston Jan Jones Larry O’Neal Speaker Speaker Pro Tem Majority Leader (R-Blue Ridge) (R-Milton) (R-Bonaire) 404-656-5020 (Cap) 404-656-5072 (Cap) 404-656-5052 (Cap) [email protected] 706-632-2221 (Dist) [email protected] [email protected] Matt Ramsey Matt Hatchett Sam Teasley Allen Peake Majority Whip Caucus Chair Caucus Vice Chairman Caucus Secretary (R-Peachtree City) (R-Dublin) (R-Marietta) (R-Macon) 404-656-5024 (Cap) 404-656-5025 (Cap) 404-656-5146 (Cap) 404-656-5025 (Cap) matt.ramsey matt.hatchett sam.teasley@ 478-474-5633 (Dist) @house.ga.gov @house.ga.gov house.ga.gov allen.peake @house.ga.gov Minority Party Stacey Abrams Carolyn Hugley Scott Holcomb Minority Leader Majority Whip Chief Deputy Whip (D-Atlanta) (D-Columbus) (D-Atlanta) 404-656-5058 (Cap) 404-656-5058 (Cap) 404-656-6372 (Cap) [email protected] 706-687-4327 (Dist) scott.holcomb carolyn.hugley @house.ga.gov @house.ga.gov Virgil Fludd Billy Mitchell Debbie Buckner David Wilkerson Caucus Chairman Caucus Secretary Treasurer -

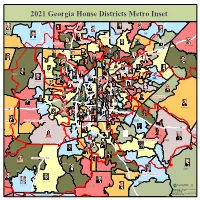

§¨¦75 §¨¦20 §¨¦85 §¨¦75 §¨¦20 §¨¦85 §¨¦85

20212021 GeorgiaGeorgia HouseHouse DistrictsDistricts MetroMetro InsetInset Amicalola EMC Lauren McDonald III (R-26) Shrri Gilligan (R-24) Mandi Ballinger (R-23) Mitchell Scoggins (R-14) Emory Dunahoo (R-30) Wes Cantrell (R-22) Hall Cherokee Forsyth Bartow §¨¦985 Sawnee EMC Matthew Gambill (R-15) Jackson Brad Thomas (R-21) Cobb EMC Charlice Byrd (R-20) David Clark (R-98) Tommy Benton (R-31) Todd Jones (R-25) Timothy Barr (R-103) 75 §¨¦ Jan Jones (R-47) §¨¦85 §¨¦575 Jackson EMC John Carson (R-46) Chuck Martin (R-49) Ed Setzler (R-35) Polk Don Parsons (R-44) Bonnie Rich (R-97) Angelika Kausche (D-50) Trey Kelley (R-16) Mary Robichaux (D-48) Gregg Kennard (D-102) Terry England (R-116) Matt Dollar (R-45) Bert Reeves (R-34) Barrow Josh McLaurin (D-51) GwinnettBeth Moore (D-95) Pedro "Pete" Marin (D-96) Samuel Park (D-101) Chuck Efstration (R-104) Ginny Ehrhart (R-36) Paulding Dewey McClain (D-100) Mary Frances Williams (D-37) Martin Momtahan (R-17) §¨¦285 Michael Wilensky (D-79) Cobb Sharon Cooper (R-43) Teri Anulewicz (D-42) Shelly Hutchinson (D-107) Donna McLeod (D-105) Joseph Gullett (R-19) Shea Roberts (D-52) Marvin Lim (D-99) Michael Smith (D-41) Scott Holcomb (D-81) Matthew Wilson (D-80) David Wilkerson (D-38) Jasmine Clark (D-108) Erick Allen (R-40) Rebecca Mitchell (D-106) Betsy Holland (D-54) Tom Kirby (R-114) Billy Mitchell (D-88) Karen Bennett (D-94) Mary Margaret Oliver (D-82) Earnest "Coach" Williams (D-87) Walton EMC Sheila Jones (D-53) Erica Thomas (D-39) Walton §¨¦285 Dar'Shun Kendrick (D-93) DeKalb Karla Drenner (D-85) Kimberly Alexander (D-66) Zulma Lopez (D-86) Micah Gravley (R-67) Mesha Mainor (D-56) Stacy Evans (D-57) Renitta Shannon (D-84) Bruce Williamson (R-115) §¨¦20 Roger Bruce (D-61) Douglas Marie Metze (D-55) Bee Nyguyen (D-89) William Boddie (D-62) Fulton Park Cannon (D-58) Doreen Carter (D-92) David Dreyer (D-59) Becky Evans (D-83) §¨¦675 GreyStone Power Corporation Rockdale Carroll EMC Kim Schofield (D-60) J. -

When Westlaw Fuels Ice Surveillance: Legal Ethics in the Era of Big Data Policing

LAMDAN_PUBLISHERPROOF_052119.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 7/25/19 12:46 PM WHEN WESTLAW FUELS ICE SURVEILLANCE: LEGAL ETHICS IN THE ERA OF BIG DATA POLICING SARAH LAMDAN¥ ABSTRACT Legal research companies are selling surveillance data and services to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (“ICE”) and other law enforcement agencies. This Article discusses ethical issues that arise when lawyers buy and use legal research services sold by the same vendors responsible for building ICE’s surveillance systems. As the legal profession collectively pays millions of dollars for computer assisted legal research services, lawyers should consider whether doing so in the era of big data policing compromises their confidentiali- ty requirements and their obligation to supervise third party vendors. With new companies developing legal research services, lawyers have more options than ever and can choose to purchase legal research services from socially responsi- ble vendors. I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 255 II. THE EVOLUTION OF ICE SURVEILLANCE: AN OVERVIEW ............................. 262 A. The Origins of Immigrant Surveillance ..................................................... 262 B. The Development of Contemporary Immigrant Surveillance .................... 262 C. ICE’s Current Surveillance Apparatus ....................................................... 265 III. LEGAL RESEARCH COMPANIES’ ROLES IN ICE SURVEILLANCE .................. 272 A. Corporate Models Shift Toward -

Possible Criminal Activity Afoot:” the Politics of Race and Boundary-Making in the United States Pacific Northwest Borderland

“Possible Criminal Activity Afoot:” The Politics of Race and Boundary-Making in the United States Pacific Northwest Borderland Leigh Barrick1 Department of Geography University of British Columbia [email protected] Abstract In northwestern Washington State, the United States Border Patrol expanded its operations inland from the international boundary with Canada in 2007. The expansion resulted in the frequent questioning and detention of community members who are Latino, non-timber forest workers, and people of color until such practices became less common by 2012. These tactics reflect a broader pattern of racial profiling through inland policing implemented across the US border with Canada. In this paper, I make the case for a critical race approach to understanding bordering practices in settings coded as ‘peaceful’ or without racial tensions. Towards this end, I analyze how racialized exclusions in northwestern Washington are articulated across scales, from local forest management, to federal policy. Further, I trace the relational construction of the western US borderlands with Canada and Mexico – spaces connected by a common heritage of conquest, although generally not conceptualized as such. My argument is that racial thinking is inherent to the production and maintenance of United States borders. A critical race approach is crucial at a time when practices carried out in the name of ‘homeland security’ threaten the wellbeing of borderland communities. 1 Published under Creative Commons licence: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works Possible Criminal Activity Afoot 900 Introduction If, as Gloria Anzaldúa (1987, 3) so eloquently put it, “The US-Mexican border es una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the First and bleeds,” then the US-Canada boundary is perhaps a wound that has scarred over.