Creatve Practce and Gender in Direct Animaton by Kayla Parker A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Love Land Rovers?

The Post Your Local Community Magazine Over 4800 copies Number 267 April 2018 Published by PostDatum, 24 Stone Street, Llandovery, Carms SA20 0JP Tel: 01550 721225 The Welsh Festival of Land Rovers at the Spring Festival will feature a broad selection of vehicles covering the Land Rover’s long and varied history. Photo credit: A Kendall / Shenstone Photography LOVE LAND ROVERS? Then you’ll love THE ROYAL WELSH SPRING FESTIVAL THIS YEAR… Land Rover enthusiasts are in for a treat at this year’s As well as a static display of lots of interesting Royal Welsh Spring Festival. vehicles and the opportunity to chat with South Wales Being held at the showground in Llanelwedd, Builth Land Rover Club members, Land Rover owners and Wells on the 19 & 20 May 2018, the festival is excitedly fellow fanatics, you will also be able to enjoy a parade of working with the South Wales Land Rover Club the vehicles in the ring on Saturday afternoon at 5.15pm, (SWLRC) to host the very first Welsh Festival of Land complete with interactive and entertaining commentary. Rovers, to make the 70th anniversary of the launch of The Royal Welsh Spring Festival is a fantastic the Landy. weekend-long celebration of smallholding and rural A huge part of many people’s lives since 1948, the life, packed full of interesting things to see, delicious Land Rover has been used by HM The Queen, Churchill, food and drink, live music, country sports, livestock, Bond, Lara Croft, Steve McQueen, Ben Fogle, Marilyn shopping, demonstrations and fun, Monroe, British Armed Forces, farmers and many more. -

Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles' Films

“All I’ve got to do is Act Naturally”: Issues of Image and Performance in the Beatles’ Films Submitted by Stephanie Anne Piotrowski, AHEA, to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English (Film Studies), 01 October 2008. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which in not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (signed)…………Stephanie Piotrowski ……………… Piotrowski 2 Abstract In this thesis, I examine the Beatles’ five feature films in order to argue how undermining generic convention and manipulating performance codes allowed the band to control their relationship with their audience and to gain autonomy over their output. Drawing from P. David Marshall’s work on defining performance codes from the music, film, and television industries, I examine film form and style to illustrate how the Beatles’ filmmakers used these codes in different combinations from previous pop and classical musicals in order to illicit certain responses from the audience. In doing so, the role of the audience from passive viewer to active participant changed the way musicians used film to communicate with their fans. I also consider how the Beatles’ image changed throughout their career as reflected in their films as a way of charting the band’s journey from pop stars to musicians, while also considering the social and cultural factors represented in the band’s image. -

Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur, Chhattisgarh

PT. RAVISHANKAR SHUKLA UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH FACULTY OF LAW(ORDINANCE No. 179) ORDINANCE, SCHEME OF EXAM AND SYLLABUS OF B.A.LL.B. (FIVE YEAR INTEGRATED DEGREE COURSE) SEMESTER SYSTEM EXAMINATION 2014-15 PUBLISHED BY SCHOOL OF P.G. STUDIES AND RESEARCH IN LAW FOR REGISTRAR PT. RAVISHANKAR SHUKLA UNIVERSITY RAIPUR, CHHATTISGARH 1 Pt. Ravishankar Shukla University Raipur, Chhattisgarh Revised ordinance No.179 B.A.LL.B. FIVE YEARS INTEGRATED DEGREE COURSE (Semester System) 1. The whole period of this integrated B.A.LL.B course divided into five academic years/ classes known as B.A.LL.B Semester first, second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eight, ninth and tenth semesters respectively. Every year /class is divided into Two Semesters WINTER and SUMMER Semesters. The examination of winter semester of all the classes will be called as WINTER TERM EXAMINATION and the other one would be known as SUMMER TERM EXAMINATION. In other words the course is extended into TEN SEMESTERS. The winter semesters are known as ODD semesters ( I, III, V, VII , IX ) while the summer semesters are known as EVEN semesters ( II, IV, VI, VIII , X ). 2. The details syllabus/ course of studies for each semester/ academic year and marking scheme for examination, etc. for this course shall be framed and approved by the Board of Studies and Law faculty duly constituted in accordance with the provision of the University Statute and Act. The syllabus forming bodies can amend/ modify the syllabus if needed in the light of BCI norms, time to time. 3. The semester academic schedule shall be framed by the University authorities according to the guidelines of BCI, and may be changed if needed. -

Milestone Film and the British Film Institute Present

Milestone Film and the British Film Institute present “She was born with magic hands.” — Jean Renoir on Lotte Reiniger A Milestone Film Release PO Box 128 • Harrington Park, NJ 07640 • Phone: (800) 603-1104 or (201) 767-3117 Fax: (201) 767-3035 • Email: [email protected] • www.milestonefilms.com The Adventures of Prince Achmed Die Abenteur des Prinzen Achmed (1926) Germany. Black and White with Tinting and Toning. Aspect Ratio: 1:1.33. 72 minutes. Produced by: Comenius-Film Production ©1926 Comenius Film GmbH © 2001 Primrose Film Productions Ltd. Based on stories in The Arabian Nights. Crew: Directed by ........................................Lotte Reiniger Animation Assistants..........................Walther Ruttmann, Berthold Bartosch and Alexander Kardan Technical Advisor..............................Carl Koch Original Music by..............................Wolfgang Zeller Restoration by the Frankfurt Filmmuseum. Tinted and printed by L'immagine ritrovata in Bologna. The original score has been recorded for ZDF/Arte. Scissors Make Films” By Lotte Reiniger, Sight and Sound, Spring 1936 I will attempt to answer the questions, which I am nearly always asked by people who watch me making the silhouettes. Firstly: How on earth did you get the idea? And secondly: How do they move, and why are your hands not seen on screen? The answer to the first is to be found in the short and simple history of my own life. I never had the feeling that my silhouette cutting was an idea. It so happened that I could always do it quite easily, as you will see from what follows. I could cut silhouettes almost as soon as I could manage to hold a pair of scissors. -

The History of the Development of British Satellite Broadcasting Policy, 1977-1992

THE HISTORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF BRITISH SATELLITE BROADCASTING POLICY, 1977-1992 Windsor John Holden —......., Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD University of Leeds, Institute of Communications Studies July, 1998 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others ABSTRACT This thesis traces the development of British satellite broadcasting policy, from the early proposals drawn up by the Home Office following the UK's allocation of five direct broadcast by satellite (DBS) frequencies at the 1977 World Administrative Radio Conference (WARC), through the successive, abortive DBS initiatives of the BBC and the "Club of 21", to the short-lived service provided by British Satellite Broadcasting (BSB). It also details at length the history of Sky Television, an organisation that operated beyond the parameters of existing legislation, which successfully competed (and merged) with BSB, and which shaped the way in which policy was developed. It contends that throughout the 1980s satellite broadcasting policy ceased to drive and became driven, and that the failure of policy-making in this time can be ascribed to conflict on ideological, governmental and organisational levels. Finally, it considers the impact that satellite broadcasting has had upon the British broadcasting structure as a whole. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract i Contents ii Acknowledgements 1 INTRODUCTION 3 British broadcasting policy - a brief history -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

A Republic of Lost Peoples: Race, Status, and Community in the Eastern Andes of Charcas at the Turn of the Seventeenth Century A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Nathan Weaver Olson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Sarah C. Chambers August 2017 © Nathan Weaver Olson 2017 Acknowledgements There is a locally famous sign along the highway between the Bolivian cities of Vallegrande and El Trigal that marks the turn-off for the town of Moro Moro. It reads: “Don’t say that you know the world if you don’t know Moro Moro.” Although this dissertation began as an effort to study the history of Moro Moro, and more generally the province of Vallegrande, located in the Andean highlands of the department of Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the research and writing process has made me aware of an entire world of Latin American history. Thus, any recounting of the many people who have contributed to this project must begin with the people of Moro Moro themselves, whose rich culture and sense of regional identity first inspired me to learn more about Bolivian history. My companions in that early journey, all colleagues from the Mennonite Central Committee, included Patrocinio Garvizu, Crecensia García, James “Phineas” Gosselink, Dantiza Padilla, and Eloina Mansilla Guzmán, to name only a few. I owe my interest and early academic grounding in Colonial Latin American history to my UCSD professors Christine Hunefeldt, Nancy Postero, Eric Van Young, and Michael Monteón. My colleagues at UCSD’s Center for Iberian and Latin American Studies and the Dimensions of Culture Writing Program at UCSD’s Thurgood Marshall College made me a better researcher and teacher. -

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92

Appendix A: Non-Executive Directors of Channel 4 1981–92 The Rt. Hon. Edmund Dell (Chairman 1981–87) Sir Richard Attenborough (Deputy Chairman 1981–86) (Director 1987) (Chairman 1988–91) George Russell (Deputy Chairman 1 Jan 1987–88) Sir Brian Bailey (1 July 1985–89) (Deputy Chairman 1990) Sir Michael Bishop CBE (Deputy Chairman 1991) (Chairman 1992–) David Plowright (Deputy Chairman 1992–) Lord Blake (1 Sept 1983–87) William Brown (1981–85) Carmen Callil (1 July 1985–90) Jennifer d’Abo (1 April 1986–87) Richard Dunn (1 Jan 1989–90) Greg Dyke (11 April 1988–90) Paul Fox (1 July 1985–87) James Gatward (1 July 1984–89) John Gau (1 July 1984–88) Roger Graef (1981–85) Bert Hardy (1992–) Dr Glyn Tegai Hughes (1983–86) Eleri Wynne Jones (22 Jan 1987–90) Anne Lapping (1 Jan 1989–) Mary McAleese (1992–) David McCall (1981–85) John McGrath (1990–) The Hon. Mrs Sara Morrison (1983–85) Sir David Nicholas CBE (1992–) Anthony Pragnell (1 July 1983–88) Usha Prashar (1991–) Peter Rogers (1982–91) Michael Scott (1 July 1984–87) Anthony Smith (1981–84) Anne Sofer (1981–84) Brian Tesler (1981–85) Professor David Vines (1 Jan 1987–91) Joy Whitby (1981–84) 435 Appendix B: Channel 4 Major Programme Awards 1983–92 British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) 1983: The Snowman – Best Children’s Programme – Drama 1984: Another Audience With Dame Edna – Best Light Entertainment 1987: Channel 4 News – Best News or Outside Broadcast Coverage 1987: The Lowest of the Low – Special Award for Foreign Documentary 1987: Network 7 – Special Award for Originality -

30 Century Man

SCOTT WALKER - 30 CENTURY MAN Directed by Stephen Kijak Produced by Mia Bays Elizabeth Rose Stephen Kijak Executive Producer David Bowie Narrated by Sara Kestelman Featuring David Bowie, Damon Albarn, Brian Eno, Jarvis Cocker, Alison Goldfrapp, Lulu, Johnny Marr, Radiohead, Sting And Scott Walker Release Date: 27 April 2007, RT and CERT tbc For press enquiries please contact: Caroline Henshaw / Alice Howell at Rabbit Publicity, Tel: 020 7299 3685 / 020 7299 3686 [email protected] / [email protected] To download photography please go to: www.vervepics.com www.scottwalkerfilm.com SCOTT WALKER - 30 CENTURY MAN _____________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION “Wow. That’s…that’s amazing. I’ve seen God in the window. That really got me…he’s been my idol since I was a kid…I’m…I’m speechless really. That’s very moving…” David Bowie, during his 50th Birthday Special on Radio 1, having listened to a recorded surprise birthday greeting from the elusive Scott Walker. Who can render David Bowie speechless? Who recorded Johnny Marr’s “favorite song of all time?” Who does Radiohead turn to time and time again as an inspirational touchstone? Who was bigger than the Beatles and the Stones for a shining moment, but turned away from fame only to morph into one of the most enigmatic and reclusive living legends in music today? THE MAN IS SCOTT WALKER. BUT WHO IS SCOTT WALKER? Called the “greatest voice of his generation," he was the lead singer of 60's sensation The Walker Brothers ("The Sun Aint' Gonna Shine Anymore") His fan club outnumbered the Beatles’ in 1965. -

S1867 16071609 0

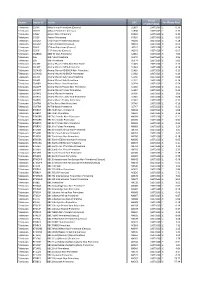

Period Domain Station ID Station UDC Per Minute Rate (YYMMYYMM) Television CSTHIT 4Music Non-Primetime (Census) S1867 16071609 £ 0.36 Television CSTHIT 4Music Primetime (Census) S1868 16071609 £ 0.72 Television C4SEV 4seven Non-Primetime F0029 16071608 £ 0.30 Television C4SEV 4seven Primetime F0030 16071608 £ 0.60 Television CS5USA 5 USA Non-Primetime (Census) H0010 16071608 £ 0.28 Television CS5USA 5 USA Primetime (Census) H0011 16071608 £ 0.56 Television CS5LIF 5* Non-Primetime (Census) H0012 16071608 £ 0.34 Television CS5LIF 5* Primetime (Census) H0013 16071608 £ 0.67 Television CSABNN ABN TV Non-Primetime S2013 16071608 £ 7.05 Television 106 alibi Non-Primetime S0373 16071608 £ 2.52 Television 106 alibi Primetime S0374 16071608 £ 5.03 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Non-Primetime S1445 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSEAPE Animal Planet EMEA Primetime S1444 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Non-Primetime S1483 16071608 £ 0.10 Television CSDAHD Animal Planet HD EMEA Primetime S1482 16071608 £ 0.19 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Non-Primetime S1530 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSEAPI Animal Planet Italy Primetime S1531 16071608 £ 0.16 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Non-Primetime S0399 16071608 £ 0.54 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Non-Primetime S1556 16071608 £ 0.11 Television CSDAPP Animal Planet Poland Primetime S1557 16071608 £ 0.22 Television CSANPL Animal Planet Primetime S0400 16071608 £ 1.09 Television CSAPTU Animal Planet Turkey Non-Primetime S1946 16071608 £ 0.08 Television CSAPTU Animal -

2007-2008 Annual Report

07_08 ANNUAL REPORT 07_08 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Friends: The 2007-08 season at YBCA has once again proven to be one of Not to be overlooked, the financial figures that are here will dem- significant accomplishment. onstrate the fiscal responsibility that is the hallmark of our work at As you will see by looking through this annual report, our artistic YBCA. We take very seriously the responsibility invested in us not endeavors continue unabated. While it is always difficult to select only by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency but also by the only a few highlights from any given season, I would certainly be foundations, individuals and corporations who believe in the work remiss if I did not point to exhibitions such as The Missing Peace: that we do and make their contributions accordingly. I am particularly Artists Consider the Dalai Lama, Anna Halprin: At the Origin of proud to note a major gift from the Novellus Systems, Inc. to name Performance and Dark Matters: Artists See the Impossible, as true the theater at YBCA. This is an amazing gift that will come to us over achievements for YBCA. Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, the next ten years and will be invested in programs at YBCA. Faustin Linyekula and Ilkhom Theatre brought us extraordinary I can say without hesitation that the staff of YBCA are dedicated, performance from around the world and Marc Bamuthi Joseph, a committed and enthusiastic about the work that we do. Without their Bay Area artist with whom we have a long-standing relationship, extraordinary effort, we would not be able to accomplish as much as opened his new piece, the break/s, here at YBCA and it has gone we do. -

Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don Mclean 1972 4

AS VOTED AT OLDIESBOARD.COM 10/30/17 THROUGH 12/4/17 CONGRATULATIONS TO “HEY JUDE”, THE #1 SELECTION FOR THE 19 TH TIME IN 20 YEARS! Ti tle Artist Year 1 Hey Jude Beatles 1968 2 (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction Rolling Stones 1965 3 American Pie Don McLean 1972 4 Light My Fire Doors 1967 5 In The Still Of The Nite Five Satins 1956 6 I Want To Hold Your Hand Beatles 1964 7 MacArthur Park Richard Harris 1968 8 Rag Doll Four Seasons 1964 9 God Only Knows Beach Boys 1966 10 Ain't No Mount ain High Enough Diana Ross 1970 11 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon and Garfunkel 1970 12 Because Dave Clark Five 1964 13 Good Vibrations Beach Boys 1966 14 Cherish Association 1966 15 She Loves You Beatles 1964 16 Hotel California Eagles 1977 17 St airway To Heaven Led Zeppelin 1971 18 Born To Run Bruce Springsteen 1975 19 My Girl Temptations 1965 20 Let It Be Beatles 1970 21 Be My Baby Ronettes 1963 22 Downtown Petula Clark 1965 23 Since I Don't Have You Skyliners 1959 24 To Sir With Love Lul u 1967 25 Brandy (You're A Fine Girl) Looking Glass 1972 26 Suspicious Minds Elvis Presley 1969 27 You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' Righteous Brothers 1965 28 You Really Got Me Kinks 19 64 29 Wichita Lineman Glen Campbell 1968 30 The Rain The Park & Ot her Things Cowsills 1967 31 A Hard Day's Night Beatles 1964 32 A Day In The Life Beatles 1967 33 Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets 1955 34 Imagine John Lennon 1971 35 I Only Have Eyes For You Flamingos 1959 36 Waterloo Sunset Kinks 1967 37 Bohemian Rhapsody Queen 76 -92 38 Sugar Sugar Archies 1969 39 What's -

Scms 2017 Conference Program

SCMS 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM FAIRMONT CHICAGO MILLENNIUM PARK March 22–26, 2017 Letter from the President Dear Friends and Colleagues, On behalf of the Board of Directors, the Host and Program Committees, and the Home Office staff, let me welcome everyone to SCMS 2017 in Chicago! Because of its Midwestern location and huge hub airport, not to say its wealth of great restaurants, nightlife, museums, shopping, and architecture, Chicago is always an exciting setting for an SCMS conference. This year at the Fairmont Chicago hotel we are in the heart of the city, close to the Loop, the river, and the Magnificent Mile. You can see the nearby Millennium Park from our hotel and the Art Institute on Michigan Avenue is but a short walk away. Included with the inexpensive hotel rate, moreover, are several amenities that I hope you will enjoy. I know from previewing the program that, as always, it boasts an impressive display of the best, most stimulating work presently being done in our field, which is at once singular in its focus on visual and digital media and yet quite diverse in its scope, intellectual interests and goals, and methodologies. This year we introduced our new policy limiting members to a single role, and I am happy to say that we achieved our goal of having fewer panels overall with no apparent loss of quality in the program or member participation. With this conference we have made presentation abstracts available online on a voluntary basis, and I urge you to let them help you navigate your way through the program.