Narrating the City and Spaces of Contestation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Century Man

SCOTT WALKER - 30 CENTURY MAN Directed by Stephen Kijak Produced by Mia Bays Elizabeth Rose Stephen Kijak Executive Producer David Bowie Narrated by Sara Kestelman Featuring David Bowie, Damon Albarn, Brian Eno, Jarvis Cocker, Alison Goldfrapp, Lulu, Johnny Marr, Radiohead, Sting And Scott Walker Release Date: 27 April 2007, RT and CERT tbc For press enquiries please contact: Caroline Henshaw / Alice Howell at Rabbit Publicity, Tel: 020 7299 3685 / 020 7299 3686 [email protected] / [email protected] To download photography please go to: www.vervepics.com www.scottwalkerfilm.com SCOTT WALKER - 30 CENTURY MAN _____________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION “Wow. That’s…that’s amazing. I’ve seen God in the window. That really got me…he’s been my idol since I was a kid…I’m…I’m speechless really. That’s very moving…” David Bowie, during his 50th Birthday Special on Radio 1, having listened to a recorded surprise birthday greeting from the elusive Scott Walker. Who can render David Bowie speechless? Who recorded Johnny Marr’s “favorite song of all time?” Who does Radiohead turn to time and time again as an inspirational touchstone? Who was bigger than the Beatles and the Stones for a shining moment, but turned away from fame only to morph into one of the most enigmatic and reclusive living legends in music today? THE MAN IS SCOTT WALKER. BUT WHO IS SCOTT WALKER? Called the “greatest voice of his generation," he was the lead singer of 60's sensation The Walker Brothers ("The Sun Aint' Gonna Shine Anymore") His fan club outnumbered the Beatles’ in 1965. -

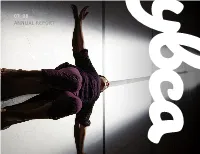

2007-2008 Annual Report

07_08 ANNUAL REPORT 07_08 ANNUAL REPORT LETTER FROM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Dear Friends: The 2007-08 season at YBCA has once again proven to be one of Not to be overlooked, the financial figures that are here will dem- significant accomplishment. onstrate the fiscal responsibility that is the hallmark of our work at As you will see by looking through this annual report, our artistic YBCA. We take very seriously the responsibility invested in us not endeavors continue unabated. While it is always difficult to select only by the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency but also by the only a few highlights from any given season, I would certainly be foundations, individuals and corporations who believe in the work remiss if I did not point to exhibitions such as The Missing Peace: that we do and make their contributions accordingly. I am particularly Artists Consider the Dalai Lama, Anna Halprin: At the Origin of proud to note a major gift from the Novellus Systems, Inc. to name Performance and Dark Matters: Artists See the Impossible, as true the theater at YBCA. This is an amazing gift that will come to us over achievements for YBCA. Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, the next ten years and will be invested in programs at YBCA. Faustin Linyekula and Ilkhom Theatre brought us extraordinary I can say without hesitation that the staff of YBCA are dedicated, performance from around the world and Marc Bamuthi Joseph, a committed and enthusiastic about the work that we do. Without their Bay Area artist with whom we have a long-standing relationship, extraordinary effort, we would not be able to accomplish as much as opened his new piece, the break/s, here at YBCA and it has gone we do. -

Scms 2017 Conference Program

SCMS 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM FAIRMONT CHICAGO MILLENNIUM PARK March 22–26, 2017 Letter from the President Dear Friends and Colleagues, On behalf of the Board of Directors, the Host and Program Committees, and the Home Office staff, let me welcome everyone to SCMS 2017 in Chicago! Because of its Midwestern location and huge hub airport, not to say its wealth of great restaurants, nightlife, museums, shopping, and architecture, Chicago is always an exciting setting for an SCMS conference. This year at the Fairmont Chicago hotel we are in the heart of the city, close to the Loop, the river, and the Magnificent Mile. You can see the nearby Millennium Park from our hotel and the Art Institute on Michigan Avenue is but a short walk away. Included with the inexpensive hotel rate, moreover, are several amenities that I hope you will enjoy. I know from previewing the program that, as always, it boasts an impressive display of the best, most stimulating work presently being done in our field, which is at once singular in its focus on visual and digital media and yet quite diverse in its scope, intellectual interests and goals, and methodologies. This year we introduced our new policy limiting members to a single role, and I am happy to say that we achieved our goal of having fewer panels overall with no apparent loss of quality in the program or member participation. With this conference we have made presentation abstracts available online on a voluntary basis, and I urge you to let them help you navigate your way through the program. -

How Joy Division Came to Sound Like Manchester: Myth and Ways of Listening in the Neoliberal City

Journal of Popular Music Studies, Volume 25, Issue 1, Pages 56–76 How Joy Division Came to Sound Like Manchester: Myth and Ways of Listening in the Neoliberal City Leonard Nevarez Vassar College Manchester, England, is among the most well-known cities today for the creation and celebration of popular music, thanks in no small part to the group Joy Division. Among the first bands to be associated with a postpunk aesthetic, Joy Division eschewed punk’syouthful rage and unrelenting din for an expansive, anthemic sound distinguished by its dynamic scope, machinic pulses, and by singer Ian Curtis’ssonorous baritone and existential lyrics. As the first significant band to sustain a career in Manchester, thus bypassing the music industry headquartered in London, Joy Division is also recognized as pioneering the DIY tradition that has famously characterized Manchester’s musical economy over the last four decades. The group didn’t achieve this alone; the role of Manchester label Factory Records is well documented, as, increasingly, is the foundation laid by the city’s networks of musicians, scene participants, and cultural institutions (see Crossley; Botta).´ Yet these local facts don’t quite explain the contemporary resonance of Joy Division’s Manchester roots for music fans and city boosters today. Perhaps more than any other Mancunian band, Joy Division are claimed to sound like Manchester, at least the Manchester of a certain era. That is, the group did not just originate from the late 1970s Manchester of deindustrialization, carceral housing estates, Thatcherism, and punk’s youthful refusal; nor do they simply illustrate a recurring Mancunian ethos of creative pluck and insouciant disregard for London’s cultural hegemony (Haslam, Manchester, England). -

Radiohead: the Guitar Weilding, Dancing, Singing Commodity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Theses Department of Communication 2-23-2009 Radiohead: The Guitar Weilding, Dancing, Singing Commodity Selena Michelle Lawson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lawson, Selena Michelle, "Radiohead: The Guitar Weilding, Dancing, Singing Commodity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_theses/47 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADIOHEAD: THE GUITAR WEILDING, DANCING, SINGING COMMODITY by SELENA LAWSON Under the Direction of Jeffery Bennett ABSTRACT In 2007, Radiohead released a downloadable album, In Rainbows, allowing consumers to pay what they thought the album was worth. The band responded to a moment of change in the music industry. Since then, other bands, like Nine Inch Nails and Coldplay, have made similar moves. Radiohead's capability to release an album and let the fans decide its worth relied on the image they built, which foregrounded their commodification. The historic move redefined the boundaries between art and commodity, a well know tension in popular music studies. The thesis focuses on popular music as communication in the changing industry. Using Radiohead’s album as a case study, it looks at the changing boundaries in the tension between art and commodity. The thesis examines Radiohead's performance, its mediation by the press, and what the album’s distribution method meant to the fans. -

A Study to Understand Manchester's Emergence As

A STUDY TO UNDERSTAND MANCHESTER’S EMERGENCE AS A CREATIVE CITY. Jordan Strong History BA Honours dissertation Aberystwyth University 9th May 2014 1 Acknowledgements Throughout this piece of work I have had some fantastic support, critiques and feedback, never more so then from Barbara Jones of student support at the university. Her support, motivation and editing of this piece of work has been second to none. The process of writing a dissertation is a hard task as it is without the persistence of dyslexia, but with Barbara’s help, the process has been as smooth as one could hope. It has been a long, hard process with some laughs along the way, I am truly grateful for her help. I would also like to thank Dr. Richard Coopey, his supervision has been excellent, his guidance with source material has been extremely beneficial to this study. Furthermore I would like to thank Suzannah Reeves of Oldham sixth form college for helping me contact Dave Haslem, Also Dave himself for taking time out to email me. Finally those who helped me at the Museum of Science and Industry during in the couple of days I spent at the Rob Gretton Archive. 2 Table of content 1. Introduction p.3 2. Chapter One – ‘The scene is very humdrum’ p.7 3. Chapter Two – ‘Evidently Chickentown’ p.14 4. Chapter Three – ‘The Hacienda must be built’ p.25 5. Chapter Four – ‘I don’t have to see my soul he is already in me’ p.39 6. Conclusion p.44 3 Introduction On the 16th of August, 1819, eighteen people were massacred during a peaceful protest in Manchester’s St. -

Making Rock History out of Ian Curtis and Joy Division

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 9, No. 4, November 2013 When Performance Lost Control: Making Rock History out of Ian Curtis and Joy Division J. Rubén Valdés Miyares 1. “Who is right, who can tell, and who gives a damn right now”1 This is a case study of the continuities between living, performing and writing. When Ian Curtis hanged himself at the age of 23, tortured by epilepsy, medication, fear and remorse; having just started a promising career as singer and songwriter for the band Joy Division, after releasing two intriguing long plays and a hit single called “Love Will Tear Us Apart”, and about to embark on their first American tour, he was stag- ing his ultimate performance. The act turned him into a cult figure, as it gave an eerie resonance to the increasingly gloomy lyrics he had written for his band. Music journalists began to write about Joy Division in a more vivid, dramatic way. People who had never seen the band perform live, or even heard of them while Curtis was alive, became fans. Joy Division was hailed in their native Manchester, England, as youthful symbols of the postmodern city, and in the rest of the world as founders of the gothic rock scene. They were subsequently the subject of biographies, biopics and documentaries which focused particularly on Curtis’s personality, and the main webpage devoted to the band (joydivisioncentral.com) lists about twenty Joy Division tribute bands performing their songs, while Youtube enables fans and critics to watch the band perform at several gigs on very low quality footage, and much more visually appealing clips of actor Sam Riley performing as Ian Curtis in the biopic about him, Control (2007). -

Brett Turnbull - Director of Photography Tel: +44 7796 953 837

Brett Turnbull - Director of Photography tel: +44 7796 953 837 . email: [email protected] website: www.brett-turnbull.com Selected credits Music videos Coldplay “Life in Technicolor II” Dizzee Rascal “Dreams” (CAD award winner 2005 “Best Effects Video”) The Streets “Fit But You Know It” (CAD award winner 2005 “Best Video”) Will Young “Who Am I” Klonherz “ Three Girl Rhumba” Dir: Dougal Wilson Prod: Colonel Blimp / Blink Travis “Re-Offender” Dir: Anton Corbijn Prod: State U2 “Magnificent” (special effects DOP) Kaiser Chiefs “Good Day Bad Days” Dir: Alex Courtes Prod: Partizan Bryan Adams “You’ve Been a Friend to Me” Dir: Bryan Adams Prod: Cheese The Ordinary Boys “Boys Will be Boys” “Life Will be the Death of Me” Dir: Andy Hylton Prod: Exposure The Feeling “Fill My Little World” Dir: Jon Riche Prod: Therapy The Enemy “We’ll Live and Die in These Towns” Dir: Barnaby Roper Prod: Flynn Paul Weller “Wishing on a Star” “From the Floorboards Up” ”Brushed” Tiffany Page “On Your Head” Dir: Lawrence Watson Prod: Medialab, CCLab, Get Shorty Robbie Williams “No Regrets” (2nd unit DOP) Dir: Pedro Romanyi Prod: Oil Factory Phil Collins “Heatwave” Donkeyboy “Ambitions” Dir: Brett Sullivan Prod: Steam Motion Enya “Trains and Winter Rains” Dir: Rob O’Connor Prod: Stylorouge Calvin Harris “Acceptable in the ‘80’s” Dir: Woof Wan Bau Prod: Nexus Placebo “Every Me Every You” Dir: Matthew Amos Prod: Red Star Urban Species “Woman” Todd Terry “ Something Going On” “It’s Over Love” “Ready For a New Day” Incognito “Nights Over Egypt” Dir: Brett Turnbull -

“SCOTT WALKER - 30 Century Man”

“SCOTT WALKER - 30 Century Man” Documentary feature film by Stephen Kijak Produced by Mia Bays (BAFTA nominee 2005, Oscar winner 2006 for SIX SHOOTER) Elizabeth Rose Stephen Kijak SALES AGENT : MOVIEHOUSE INTERNATIONAL UK DISTRIBUTOR : VERVE PICTURES (UK CINEMA RELEASE SPRING 2007) Executive Producer: David Bowie “Yes, there are people in the world who do not love Scott Walker. But what must their hearts be like?” – Stuart Maconie in the New Musical Express Production Notes Page 1 06/03/2007 “30 Century Man is a fascinating and entertaining exploration of one of the most extraordinary careers in pop culture. I have rarely seen a biographical documentary that is able to make the viewer experience the perspective of a devoted fan, a concerned friend, and a complete stranger at the same time. Like Scott Walker himself, this is an absolutely unique film.” Filmmaker Atom Egoyan Introduction “Wow. That’s…that’s amazing. I’ve seen God in the window. That really got me…he’s been my idol since I was a kid.…I’m…I’m speechless really. That’s very moving…” David Bowie, during his 50th Birthday Special on Radio 1, having listened to a recorded surprise birthday greeting from the elusive Scott Walker. Who can render David Bowie speechless? Who recorded Johnny Marr’s “favorite song of all time?” Who does Radiohead turn to time and time again as an inspirational touchstone? Who was bigger than the Beatles and the Stones for a shining moment, but turned away from fame only to morph into one of the most enigmatic and reclusive living legends in music today? The man is Scott Walker. -

British Music Videos and Film Culture

Scope: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies Issue 26 February 2014 The Fine Art of Commercial Freedom: British Music Videos and Film Culture Emily Caston, University of the Arts, London In the “golden era” or “boom” period of music video production in the 1990s, the UK was widely regarded throughout the world as the center for creative excellence (Caston, 2012). This was seen to be driven by the highly creative ambitions of British music video commissioners and their artists, and centered on an ideological conception of the director as an auteur. In the first part of this article, I will attempt to describe some of the key features of the music-video production industry. In the second I will look at its relationship with other sectors in British film and television production – in particular, short film, and artists’ film and video, where issues of artistic control and authorship are also ideologically foregrounded. I will justify the potentially oxymoronic concept of “the fine art of commercial freedom” in relation to recent contributions in the work of Kevin Donnelly (2007) and Sue Harper and Justin Smith (2011) on the intersection between the British “avant garde” and British film and television commerce. As Diane Railton and Paul Watson point out, academics are finally starting to recognize that music videos are a “persistent cultural form” that has outlived one of their initial commercial functions as a promotional tool (2011: 7). Exhibitions at the Museum of Moving Image (MOMI) in New York and the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT) in Liverpool have drawn the attention of Sight and Sound, suggesting that this cultural form is now on the verge of canonization (Davies, 2013). -

Power to the People: British Music Videos 1966 - 2016

Power To The People: British Music Videos 1966 - 2016 200 landmark music videos TRL314A_BKLT_R2018.indd 1 17/01/2018 12:46 Disc 1 contains Performance Videos - a genre which has its roots in mid-1960s films such Power To The People: as A Hard Day’s Night (1964). The core deceit of the performance video is that the band British Music Videos 1966 - 2016 do not perform the track live for filming but mimic performance by singing and playing their instruments in synch to audio playback of the track. Some bands and directors Introductory Essay by the curator Professor Emily Caston have rebelled against this deception to create genuine live performance videos such as Joy Division’s ‘Love Will Tear Us Apart’ (1980). There are precedents for the styles used in pre-1966 video jukebox and other short film clips. Directors who excelled in the performance genre often came from a music or record company background, or came This is a collection of some of the most important and influential music videos made in to video directing through album design. Britain since 1966. It’s the result of a three-year research project funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and run in collaboration with the British Film Institute and From the 1980s onwards video directors fashioned more and more original locations the British Library. The videos were carefully selected by a panel of over one hundred and devices for those artists who were willing to experiment with the performance directors, producers, cinematographers, editors, choreographers, colourists and video genre: Tim Pope & The Cure’s ‘Close To Me’ (1985), Sophie Muller & Blur’s ‘Song 2’ commissioners. -

Coding OK Computer: Categorization and Characterization of Disruptive Harmonic and Rhythmic Events in Rock Music

Coding OK Computer: Categorization and Characterization of Disruptive Harmonic and Rhythmic Events in Rock Music by Nathaniel Emerson Adam A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music Theory) in the University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Walter T. Everett, Chair Associate Professor Ramon Satyendra Assistant Professor Karen J. Fournier Assistant Professor Sheila C. Murphy © Nathaniel Emerson Adam 2011 To Laura Hope ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I want to acknowledge and thank my advisor and friend, Walt Everett. His work inspired me to pursue research in rock analysis, and he personally guided that pursuit, generously providing constant support and assistance. This work is a tribute to him. Many thanks also to the members of my committee, for the experiences in their classrooms and for their encouragement and suggestions in the development of this project. I must acknowledge Thom, Johnny, Ed, Colin, Phil, and Nigel for creating such beautiful and provocative music in the first place. I can’t wait to see what they do next. My love and thanks go out to Zach and to Brent for providing years of stimulating conversation and musical collaboration, and constantly challenging me to think about music better and more deeply. When I started graduate school, Blair, Phil, Danny, and David went out of their way to make me feel welcome and embrace me as a colleague. I’m extremely grateful for their example, their mentoring, and their friendship. Thanks to them and to all of my other colleagues at the University of Michigan, especially Bryan, Michael, Alison, and Abby; spending time with them made it easier to stay sane.