Journey Towards the (M)Other : Myth, Origins And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quest for Female Empowerment in Angela Carter's Wise Children

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN Supervisor: Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of Professor Marysa Demoor the requirements for the degree of “Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Aline Lapeire 2009-2010 Lapeire ii Lapeire iii “I AM NOT SURE IF THIS IS A HAPPY ENDING” THE QUEST FOR FEMALE EMPOWERMENT IN ANGELA CARTER’S WISE CHILDREN The cover of Wise Children (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007) Lapeire iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation could not have been written without the help of the following people. I would hereby like to thank… … Professor MARYSA DEMOOR for supporting my choice of topic and sharing her knowledge about gender studies. Her guidance and encouragement have been very important to me. … DEBORA VAN DURME and Professor SINEAD MCDERMOTT for their interesting class discussions of Nights at the Circus and Wise Children. Without their keen eye for good fiction, I might have never even heard of Angela Carter and her beautiful oeuvre. … Several very patient librarians at the University of Ghent. … A great deal of friends who at times mocked the idea of a „gender dissertation‟, yet always showed their support when it was due. I especially want to thank my loyal thesis buddies MAX DEDULLE and MARTIJN DENTANT. The countless hours we spent together while hopelessly staring at a world behind the computer screen eventually did pay off. Moreover, eternal gratitude and a vodka-Red Bull go out to JEROEN MEULEMAN who entirely voluntarily offered to read and correct my thesis. -

The Consumption of Angela Carter

The Consumption of Angela Carter: Women, Toody and Power EMMA PARKER A great writer and a great critic, V. S. Pritchett, used to sav that he swallowed Dickens whole, at the risk of indigestion. I swallow Angela Carter whole, and then I rush to buy Alka Seltzer. The "minimalist" nouvelle cuisine alone cannot satisfy my appetite for fiction. I need a "maximalist" writer who tries to tell us many things, with grandiose happenings to amuse me, extreme emotions to stir my feelings, glorious obscenities to scandalise me, brilliant and malicious expressions to astonish me. (Almansi 217) L Vs GUIDO ALMANSI suggests, consuming Angela Carter's fic• tion is simultaneously satisfying and unsettling. This is partly because, as Hermione Lee has commented, Carter "was always in revolt against the 'tyranny of good taste'" (316). As a cham• pion of moral pornography, a cultural dissident who dared to disparage Shakespeare, and a culinary iconoclast who criticised the highly-esteemed cookery writer Elizabeth David, Carter out• raged many people. Yet this impiety also gives her work its ap• peal.1 Like the critical essays, her fiction is deliciously "improper" in that it interrogates and rejects what Hélène Cixous calls the realm of the proper, a masculine economy based on the principles of authority, domination and owner• ship — a realm in which, disempowered and dispossessed, women are without property ("Castration" 42, 50). Her fiction has an unsettling effect precisely because Carter seeks to "up• set" the patriarchal order, in part through her representation of consumption, which, by revealing and refiguring the relation• ship between women, food, and power, challenges the struc• tures that underpin patriarchy. -

Identity I N Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children

Performing (and) Identity In Angela Carter's Nights at the Circus and Wise Children Janine Root @ B .A. B. Ed A cnesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Lakehead University, Thnder Bay, Ontario, 1999 National Library BibliotMy nationale 1*1 ofCanada du Cana a Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wauinglm Strwt 385. rue WdlingWn WONK1AW o(I.waON K1AW Cwudr CMed. The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Libmy of Cana& to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, prster, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la fome de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent &e imprimes reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. Abstract In her last two novels, Nights at the Circus and Wise Children, Angela Carter examines some of the complex factors involved in the construction of identity, both within the fictional world, and for readers in their interaction with 'Le .jn-74 ,., I ,,,, 2f the fictix. 35 zhese f3ctxs, qezier is cf primary importance. -

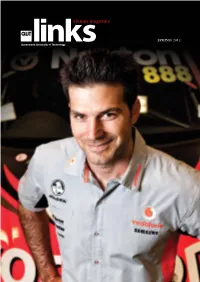

QUT Links Alumni Magazine Spring 2012

alumni magazine SPRING 2012 contentsVOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 Profiles Features Wayne Blair’s The QUT’s Outstanding Sapphires lauded by film Alumni Award winners 9 critics and audiences. 1-6 are revealed. Mother-daughter maths Welcome to the future teaching duo go bush. of interactive learning – 14 11 The Cube. Attorney General Jarrod Bleijie has legislative Bouquets of caring 15 reform on his agenda. recognise Queensland 20 community gems. 4 Student leader Erin Gregor is an impressive 19 all-rounder. Research Regulars New frontier opens for NEWS ROUNDUP 8 10 space glass. RESEARCH UPDATE 18 Rats inspire GPS camera ALUMNI NEWS 21-23 9 technology. 12 KEEP IN TOUCH 24 Heart attack care study LAST WORD rates towns nationwide. 13 by Vice-Chancellor Professor Peter Coaldrake Vice-Chancellor fellows lead the pack in - SEE INSIDE BACK COVER 16 innovative research. Transcend physical and spiritual limits 17 through sport. 17 alumni magazine links Editor Stephanie Harrington p: 07 3138 1150 e: [email protected] Contributors Rose Trapnell Alita Pashley Niki Widdowson Mechelle McMahon Rachael Wilson Images Erika Fish In focus Design Richard de Waal Philanthropist Tim Fairfax is QUT’s distinguished QUT Links is published by QUT’s 7 new Chancellor. Marketing and Communication Department in cooperation with QUT’s Alumni and Development Office. Editorial material is gathered from a range of sources and does not necessarily reflect the opinions and policies of QUT. CRICOS No. 00213J QUTLINKS SPRING ’12 1 Outstanding Young Alumnus Award Winner Mark Dutton Thinker WHEN reigning V8 Supercars champion Jamie Whincup speeds off at the start line, Mark Dutton’s FAST feet are planted firmly on the ground. -

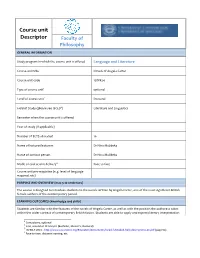

Course Unit Descriptor

Course unit Descriptor Faculty of Philosophy GENERAL INFORMATION Study program in which the course unit is offered Language and Literature Course unit title Novels of Angela Carter Course unit code 15DFk24 Type of course unit1 optional Level of course unit2 Doctoral Field of Study (please see ISCED3) Literature and Linguistics Semester when the course unit is offered Year of study (if applicable) Number of ECTS allocated 10 Name of lecturer/lecturers Dr Nina Muždeka Name of contact person Dr Nina Muždeka Mode of course unit delivery4 Face to face Course unit pre-requisites (e.g. level of language required, etc) PURPOSE AND OVERVIEW (max 5-10 sentences) The course is designed to introduce students to the novels written by Angela Carter, one of the most significant British female authors of the contemporary period. LEARNING OUTCOMES (knowledge and skills) Students are familiar with the features of the novels of Angela Carter, as well as with the position the authoress takes within the wider context of contemporary British fiction. Students are able to apply and express literary interpretation 1 Compulsory, optional 2 First, second or third cycle (Bachelor, Master's, Doctoral) 3 ISCED-F 2013 - http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/isced-f-detailed-field-descriptions-en.pdf (page 54) 4 Face-to-face, distance learning, etc. effectively. SYLLABUS (outline and summary of topics) Lectures Angela Carter, contemporary British novel, feminist theory and engaged writing. Shadow Dance as parodic contemporary gothic fiction. Let’s begin countering patriarchal stereotypes: The Magic Toyshop. Several Perceptions: generation gap and the counterculture of the 60s. -

The Republican Journal: Vol. 80, No. 27

■■ —1 ■— ■ ■ — ■ ■ ■ _ -" _.The Republican Journal. BELFAST, MAINE, THURSDAY, JULY 2, 1908.__NUMBER 27 land Knowlton, Giles G. Abbott, W. E. ^ BELLS. THE CHURCHES. I Waj MAJ. J. A. FESSENDEN DEAD. vUDDING IHE NEWSOE RELEASE Jones, H. Fair Holmes, Enoch C. Dow, PERSONAL. PERSONAL. Amos Coloord. On motion of F. A. Greer Gallant Record as a Soldier. Served With The marriage of will be services at the St. Francis Bobbins. There were instructed to support Notable Honor in Civil Re- Eddie left Monday for a visit in Miss Maria Andrews went to Carncen last If the person who found the black serge the delegates War, and, llogon ,,( Omaha, Neb., formerly Catholic church next Sunday at 10 o’clock Gardner of Rockland for week to visit friends. with a Hon. Obadiah from Became a Portland. Elizabeth Knowlton coat, gray lining, made at Hovey's, tiring Regular Army, ; Miss a. no The were which was governor. following delegates in Public Affairs in of Mass., ar- Miss Sadie Wright left, of Boston, lost about town or on Conspicuous Figure George Keyes Middleboro, by Saturday's ,Mon, formerly Belfast, Poor’s Mills to attend the county convention: E. Rev. A. E. Luce will speak at Lincolnville avenue morning, chosen Stamford. rived last Sunday. boat, for Pittsfield, Mass. 5 ,.luesiiay evening, June 24th, Wednesday R. F. W. next at 2.30 m. All are cordial- it to S. Pitcher, John Dunton, Brown, Mrs. E. Wallace Sunday p. will return 1 Court street they will Major Joshua A. Fessenden, U. S. A., re- Judsou Jewett of Mass., is visiting 0. -

Singles 1970 to 1983

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS PHILIPS–PHONOGRAM 7”, EP’s and 12” singles 1970 to 1983 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 PHILIPS-PHONOGRAM, 1970-83 2001 POLYDOR, ROCKY ROAD, JET 2001 007 SYMPATHY / MOONSHINE MARY STEVE ROWLAND & FAMILY DOGG 5.70 2001 072 SPILL THE WINE / MAGIC MOUNTAIN ERIC BURDON & WAR 8.70 2001 073 BACK HOME / THIS IS THE TIME OF THE YEAR GOLDEN EARRING 10.70 2001 096 AFTER MIDNIGHT / EASY NOW ERIC CLAPTON 10.70 2001 112 CAROLINA IN MY MIND / IF I LIVE CRYSTAL MANSION 11.70 2001 120 MAMA / A MOTHER’S TEARS HEINTJE 3.71 2001 122 HEAVY MAKES YOU HAPPY / GIVE ‘EM A HAND BOBBY BLOOM 1.71 2001 127 I DIG EVERYTHING ABOUT YOU / LOVE HAS GOT A HOLD ON ME THE MOB 1.71 2001 134 HOUSE OF THE KING / BLACK BEAUTY FOCUS 3.71 2001 135 HOLY, HOLY LIFE / JESSICA GOLDEN EARING 4.71 2001 140 MAKE ME HAPPY / THIS THING I’VE GOTTEN INTO BOBBY BLOOM 4.71 2001 163 SOUL POWER (PT.1) / (PTS.2 & 3) JAMES BROWN 4.71 2001 164 MIXED UP GUY / LOVED YOU DARLIN’ FROM THE VERY START JOEY SCARBURY 3.71 2001 172 LAYLA / I AM YOURS DEREK AND THE DOMINOS 7.72 2001 203 HOT PANTS (PT.1) / (PT.2) JAMES BROWN 10.71 2001 206 MONEY / GIVE IT TO ME THE MOB 7.71 2001 215 BLOSSOM LADY / IS THIS A DREAM SHOCKING BLUE 10.71 2001 223 MAKE IT FUNKY (PART 1) / (PART 2) JAMES BROWN 11.71 2001 233 I’VE GOT YOU ON MY MIND / GIVE ME YOUR LOVE CAROLYN DAYE LTD. -

Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal, 2003. INSTITUTION Illinois Association for Gifted Children, Palatine

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 217 EC 309 630 AUTHOR Smutny, Joan Franklin, Ed. TITLE Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal, 2003. INSTITUTION Illinois Association for Gifted Children, Palatine. PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 66p.; Published annually. For the 2002 issue, see EC 309 629. AVAILABLE FROM Illinois Association for Gifted Children, 800 E. Northeast Highway, Suite 610, Palatine, IL 60067-6512 (nonmembers, $25). Tel: 847-963-1892; Fax: 847-963-1893. PUB TYPE Collected Works Serials (022) JOURNAL CIT Illinois Association for Gifted Children Journal; 2003 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Ability Identification; Cognitive Style; *Creativity; *Curriculum Design; *Curriculum Enrichment; Educational Strategies; Elementary Secondary Education; *Gifted; Music Activities; Poetry; Underachievement ABSTRACT This issue of the Illinois Association for Gifted Children (IAGC) Journal focuses on curriculum. Featured articles include: (1) "Curriculum: What Is It? How Do You Know if It Is Quality?" (Sally Walker); (2) "Tiered Lessons: What Are Their Benefits and Applications?" (Carol Ann Tomlinson); (3) "Do Gifted and Talented Youth Get Counseling, Models, and Mentors To Motivate Them To Strive for Expertise and Creative Achievement?" (John F. Feldhusen);(4) "Biography Is the People Subject" (Jerry Flack); (5) "Abraham Lincoln: Gifted Man and a Hero for the Ages" (Jerry Flack);(6) "Responding to Failure" (Ann MacDonald and Jim Riley); (7) "The Not-So Gifted Parent: Replacing Trial and Error with Identification and Intervention" (Monica Lu); (8) "They Don't Teach THAT in School" (Dorothy Funk-Werbio): (9) "A Poet in a Classroom of Engineers and Lawyers: Identifying and Meeting the Needs of Artistically Gifted Children" (Nancy Elf and Pat Rose); (10) "A Visit from a Poet and Other Literary Devices" (J. -

Gender, Tragedy, and the American Dream

37? /VQti N@* 37 & THE AMERICAN EVE: GENDER, TRAGEDY, AND THE AMERICAN DREAM DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Kim Martin Long, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1993 37? /VQti N@* 37 & THE AMERICAN EVE: GENDER, TRAGEDY, AND THE AMERICAN DREAM DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Kim Martin Long, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1993 Long, Kim Martin. The American Eve; Gender. Tragedy, and the American Dream. Doctor of Philosophy (English), May, 1993, 236 pp., works cited, 176 titles. America has adopted as its own the Eden myth, which has provided the mythology of the American dream. This New Garden of America, consequently, has been a masculine garden because of its dependence on the myth of the Fall. Implied in the American dream is the idea of a garden without Eve, or at least without Eve's sin, traditionally associated with sexuality. Our canonical literature has reflected these attitudes of devaluing feminine power or making it a negative force: The Scarlet Letter. Mobv-Dick. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The Great Gatsbv. and The Sound and the Fury. To recreate the Garden myth, Americans have had to reimagine Eve as the idealized virgin, earth mother and life-giver, or as Adam's loyal helpmeet, the silent figurehead. But Eve resists her new roles: Hester Prynne embellishes her scarlet letter and does not leave Boston; the feminine forces in Mobv-Dick defeat the monomanaical masculinity of Ahab; Miss Watson, the Widow Douglas, and Aunt Sally's threat of civilization chase Huck off to the territory despite the beckoning of the feminine river; Daisy retreats unscathed into her "white palace" after Gatsby's death; and Caddy tours Europe on the arm of a Nazi officer long after Quentin's suicide, Benjy's betrayal, and Jason's condemnation. -

Keir Nuttall Thesis

I’m With Muriel: Applying a Persona- Centred Songwriting Technique to the Creation of a New Australian Musical Keir Nuttall BMus Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Creative Practice Faculty of Creative Industries, Education and Social Justice QUT 2021 Table of Contents Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Statement of Original Authorship .............................................................................................. 8 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 1: Introduction............................................................................................................ 11 Situating the Researcher ............................................................................................................................. 16 Chapter 2: Literature and Contextual Review ........................................................................... 24 Part One: Authenticity and the Music Business ........................................................................ 24 The Artist vs Culture and Society ................................................................................................................ 25 -

Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives

Postmodern Openings ISSN: 2068 – 0236 (print), ISSN: 2069 – 9387 (electronic) Coverd in: Index Copernicus, Ideas. RePeC, EconPapers, Socionet, Ulrich Pro Quest, Cabbel, SSRN, Appreciative Inquery Commons, Journalseek, Scipio EBSCO Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU Postmodern Openings, 2010, Year 1, VOL.3, September, pp: 93-138 The online version of this article can be found at: http://postmodernopenings.com Published by: Lumen Publishing House On behalf of: Lumen Research Center in Social and Humanistic Sciences BOTESCU–SIRETEANU, I.,(2010) Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives, Postmodern Openings, Year 1, Vol 3, September, 2010, pp: 93-138 Angela Carter and the Violent Distrust of Metanarratives Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU8 Abstract In a world where meaning has been deconstructed and reconstructed, where centers have lost their hegemony and notions such as truth, knowledge or history have been rendered relative by the ongoing ontological enquiry of the postmodern ideology, it is baffling to remark that not only in literature, but also in other fields that make use of discourses, there has been a return to and a reconsideration of the narrative. Nowadays, one can easily observe the narrative drive that enlivens various discourses, from the medical one to the one used in the academe or in official governmental documents. Brian McHale has even referred to the „narrative turn” in literary theory which, according to him, seems to answer to the loss of the metaphysical (McHale 4). Keywords: narrative turn, feminism, narrative dynamics, 8 Ileana BOTESCU – SIRETEANU – “Transilvania” University from Brasov, Romania, Email Address: [email protected]. -

Literary Miscellany

Literary Miscellany A Selection from Recent Acquisitions and Stock Including Prose and Poetry from the 17th - 20th Centuries Association Copies and Letters Fine Printing, Illustrated Books, Film Material, And Varia of Other Sorts Catalogue 306 WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CT. 06511 USA 203.789.8081 FAX: 203.865.7653 [email protected] www.reeseco.com TERMS Material herein is offered subject to prior sale. All items are as described, but are consid- ered to be sent subject to approval unless otherwise noted. Notice of return must be given within ten days unless specific arrangements are made prior to shipment. All returns must be made conscientiously and expediently. Connecticut residents must be billed state sales tax. Postage and insurance are billed to all non-prepaid domestic orders. Orders shipped outside of the United States are sent by air or courier, unless otherwise requested, with full charges billed at our discretion. The usual courtesy discount is extended only to recognized booksellers who offer reciprocal opportunities from their catalogues or stock. We have 24 hour telephone answering and a Fax machine for receipt of orders or messages. Catalogue orders should be e-mailed to: [email protected] We do not maintain an open bookshop, and a considerable portion of our literature inven- tory is situated in our adjunct office and warehouse in Hamden, CT. Hence, a minimum of 24 hours notice is necessary prior to some items in this catalogue being made available for shipping or inspection (by appointment) in our main offices on Temple Street. We accept payment via Mastercard or Visa, and require the account number, expiration date, CVC code, full billing name, address and telephone number in order to process payment.