Keir Nuttall Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

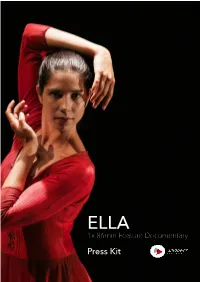

1X 86Min Feature Documentary Press Kit

ELLA 1x 86min Feature Documentary Press Kit INDEX ! CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION………………………… P3 ! PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS.…………………………………..…………………… P4-6 ! KEY CAST BIOGRAPHIES………………………………………..………………… P7-9 ! DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………… P10 ! PRODUCER’S STATEMENT………………………………………..………………. P11 ! KEY CREATIVES CREDITS………………………………..………………………… P12 ! DIRECTOR AND PRODUCER BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………. P13 ! PRODUCTION CREDITS…………….……………………..……………………….. P14-22 2 CONTACT DETAILS AND TECHNICAL INFORMATION Production Company WildBear Entertainment Pty Ltd Address PO Box 6160, Woolloongabba, QLD 4102 AUSTRALIA Phone: +61 (0)7 3891 7779 Email [email protected] Distributors and Sales Agents Ronin Films Address: Unit 8/29 Buckland Street, Mitchell ACT 2911 AUSTRALIA Phone: + 61 (0)2 6248 0851 Web: http://www.roninfilms.com.au Technical Information Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 24fps Release Format: DCP Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 86’ Production Format: 2K DCI Scope Frame Rate: 25fps Release Formats: ProResQT Sound Configuration: 5.1 Audio and Stereo Mix Duration: 83’ Date of Production: 2015 Release Date: 2016 ISAN: ISAN 0000-0004-34BF-0000-L-0000-0000-B 3 PROGRAM DESCRIPTIONS Logline: An intimate and inspirational journey of the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history Short Synopsis: In October 2012, Ella Havelka became the first Indigenous dancer to be invited into The Australian Ballet in its 50 year history. It was an announcement that made news headlines nationwide. A descendant of the Wiradjuri people, we follow Ella’s inspirational journey from the regional town of Dubbo and onto the world stage of The Australian Ballet. Featuring intimate interviews, dynamic dance sequences, and a stunning array of archival material, this moving documentary follows Ella as she explores her cultural identity and gives us a rare glimpse into life as an elite ballet dancer within the largest company in the southern hemisphere. -

2013 Helpmann Awards Winners Announced! Full List of Winners At

HELPMANN AWARDS MEDIA RELEASE MONDAY 29TH JULY 2013 2013 HELPMANN AWARDS WINNERS ANNOUNCED! FULL LIST OF WINNERS AT www.helpmannawards.com.au The 13th Annual Helpmann Awards were presented tonight live in Sydney at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House and broadcast on Foxtel’s Arena. Co-hosts Eddie Perfect and Christie Whelan Browne kicked off the night’s proceedings with an incredibly entertaining opening number written specifically for the occasion by the multi-talented Mr Perfect himself. The Helpmann Awards recognise distinguished artistic achievement and excellence across the major disciplines of Australia's live performance industry. In total 43 awards were presented this evening by some of Australia’s most celebrated talent including, Tina Arena, Baz Luhrmann, Sarah Murdoch, John Waters, Hugh Sheridan, Marcus Graham, Elizabeth Debicki, Patrick Brammall, Chloe Dallimore, Erika Heynatz, Ashley Zukerman, Miranda Tapsell, Rob Mills, Sharon Millerchip, Toby Schmitz, Alison Bell, David Harris, Wayne Scott Kermond, Lynette Curran, Christen O’Leary, Russell Dykstra, Esther Hannaford, The Hon. George Souris, Ewen Leslie, Jennifer Vuletic and Helen Thomson. Further showcasing Australia’s unique and diverse live performance industry, show highlights included live performances by Tim Minchin, the casts of GREASE and HOT SHOE SHUFFLE, Sydney Dance Company, Silvie Paladino and the Sydney Children’s Choir, Emma Birdsall and Timomatic. In addition, as previously announced pop music icon Kylie Minogue OBE and Arts philanthropist David Blenkinsop CBE AM were co-recipients of the 2013 JC WILLIAMSON AWARD. By bestowing this award, Live Performance Australia (LPA) recognises individuals who have made an outstanding contribution to the Australian live entertainment industry and shaped the future of our industry for the better. -

M-Phazes | Primary Wave Music

M- PHAZES facebook.com/mphazes instagram.com/mphazes soundcloud.com/mphazes open.spotify.com/playlist/6IKV6azwCL8GfqVZFsdDfn M-Phazes is an Aussie-born producer based in LA. He has produced records for Logic, Demi Lovato, Madonna, Eminem, Kehlani, Zara Larsson, Remi Wolf, Kiiara, Noah Cyrus, and Cautious Clay. He produced and wrote Eminem’s “Bad Guy” off 2015’s Grammy Winner for Best Rap Album of the Year “ The Marshall Mathers LP 2.” He produced and wrote “Sober” by Demi Lovato, “playinwitme” by KYLE ft. Kehlani, “Adore” by Amy Shark, “I Got So High That I Found Jesus” by Noah Cyrus, and “Painkiller” by Ruel ft Denzel Curry. M-Phazes is into developing artists and collaborates heavy with other producers. He developed and produced Kimbra, KYLE, Amy Shark, and Ruel before they broke. He put his energy into Ruel beginning at age 13 and guided him to RCA. M-Phazes produced Amy Shark’s successful songs including “Love Songs Aint for Us” cowritten by Ed Sheeran. He worked extensively with KYLE before he broke and remains one of his main producers. In 2017, Phazes was nominated for Producer of the Year at the APRA Awards alongside Flume. In 2018 he won 5 ARIA awards including Producer of the Year. His recent releases are with Remi Wolf, VanJess, and Kiiara. Cautious Clay, Keith Urban, Travis Barker, Nas, Pusha T, Anne-Marie, Kehlani, Alison Wonderland, Lupe Fiasco, Alessia Cara, Joey Bada$$, Wiz Khalifa, Teyana Taylor, Pink Sweat$, and Wale have all featured on tracks M-Phazes produced. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: Come Over VanJess Homegrown (Deluxe) Keep Cool/RCA P,W 2021 Remi Wolf Sexy Villain Single Island P,W 2021 Yung Bae ft. -

Glam Rock and Funk Alter-Egos, Fantasy, and the Performativity of Identities

REVISTA DE LENGUAS MODERNAS, N.° 26, 2017 / 387-401 / ISSN: 1659-1933 Glam Rock and Funk Alter-Egos, Fantasy, and the Performativity of Identities MONICA BRADLEY Escuela de Lenguas Modernas Universidad de Costa Rica The emergence of desire, and hence our biological response, is thus bound up in our ability to fantasize, to inhabit an imagined scenario that, in turn, ‘produces what we understand as sexuality’ (Whitely 251). Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy? Caught in a landslide, no escape from reality” (Queen, “Bohemian Rhapsody”). Abstract The following article explores different conceptions of fantasy and science fiction that characterized many popular music performances in the 1970’s predominantly in the genres of glam rock and funk. By focusing on a few artists that were at the peak of their music careers at this time, such as David Bowie, P-Funk, Queen, Labelle and others, it attempts to un-earth some historical conditions for women, queers, and people of color and reveal how these artists have attempted to escape and transform certain realities by transgressing the boundaries of real/fiction, masculinity/ femininity, race, sexuality, and the “alien”. Key words: Glam rock, Funk, music, science fiction, queer, gender, race Resumen El siguiente artículo explora las diferentes concepciones de fantasía y ciencia ficción que caracterizan muchas formas de actuación en la música popular de los años setentas, predominantemente en los géneros de glam rock y funk. Pondré especial atención en algunos artistas que estuvieron en el ápice de su carrera musical en este tiempo como David Bowie, Recepción: 29-03-16 Aceptación: 12-12-16 388 REVISTA DE LENGUAS MODERNAS, N.° 26, 2017 / 387-401 / ISSN: 1659-1933 P-Funk, Queen, Labelle, y otros quienes intentaron traer a la realidad temas sobre condiciones históricas en mujeres, queers y personas de color . -

Stuart Ayres MEDIA RELEASE

Stuart Ayres Minister for Jobs, Investment, Tourism and Western Sydney MEDIA RELEASE Saturday, 13 June 2020 NEW MUSIC EVENT BRINGS 1,000 GIGS TO SYDNEY AND NSW — HUGE BOOST FOR TOURISM AND ARTISTS A new music event will bring 1,000 COVID-safe gigs to Sydney and regional NSW in November, giving Australian artists a welcome boost and turbocharging live music venues across the state. Great Southern Nights is a NSW Government initiative delivered by its tourism and major events agency Destination NSW in partnership with the Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) to support the recovery of the live music, entertainment and hospitality industries. Minister for Jobs, Investment, Tourism and Western Sydney Stuart Ayres said the gigs would be a welcome antidote to the challenges presented by COVID-19, bushfires and the prolonged drought. “This celebration of outstanding Australian artists and incredible live music venues across NSW gives us all something to look forward to, from event-goers to industry,” Minister Ayres said. “We’ll be able to get out and see Sydney and regional NSW come to life with some of Australia’s top acts including Jimmy Barnes, Paul Kelly, Missy Higgins and Tones and I alongside emerging artists in unexpected places. “We’re inviting venues across NSW, from the bush to the city, to nominate to be involved in this exciting new event. “With the NSW Government’s 24-hour economy strategy set to reinvigorate Sydney’s nightlife, Great Southern Nights will be a big step forward for our state’s live music and hospitality community that has been hit hard in recent times.” Among the 20 headline acts to play across the music event are (in alphabetical order): • Jimmy Barnes • Birds of Tokyo • Missy Higgins • The Jungle Giants • Paul Kelly • Thelma Plum • The Presets • Amy Shark • Tash Sultana • The Teskey Brothers • Tones and I • The Veronicas Established and emerging local Australian artists will present 1,000 gigs, curated by ARIA and an industry advisory committee across a multitude of venues around NSW. -

Tom Solo Acoustic Songlist

1300 738 735 phone [email protected] email www.blueplanetentertainment.net.au web www.facebook.com/BluePlanetEntertainment Tom Solo Acoustic Songlist 3am – Matchbox Twenty 500 Miles – The Proclaimers A Thousand Years – Christina Perry Adore – Amy Shark All for You – Sister Hazel All of Me – John Legend All the Small Things – Blink 182 Am I Ever Gonna See Your Face Again – The Angels April Sun – Dragon Baby I Love Your Way – Big Mountain Better Be Home Soon – Crowded House Better Together – Jack Johnsen Billie Jean – Michael Jackson Black or White – Michael Jackson Blister in The Sun – Violent Femmes Blue Suede Shoes – Elvis Presley Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke Breakeven (Falling to Pieces) – The Script Bright Lights – Matchbox Twenty Brown Eyed Girl – Van Morrison Budapest – George Ezra Can’t Help Falling in Love – Elvis Presley Castle on The Hill – Ed Sheeran Chasing Cars – Snow Patrol Cheap Thrills – Sia Cheerleader – OMI Closer – Chainsmokers Collide – Howie Day Crazy – Gnarles Barkley Crazy Little Thing Called Love – Queen Dancing in The Dark – Bruce Springsteen Dancing in The Moonlight – Toploader Dancing in The Moonlight – Thin Lizzy Demons – Imagine Dragons Don’t – Ed Sheeran Don’t Dream It’s Over – Crowded House Don’t Stop – Fleetwood Mac Don’t Stop Believin’ – Journey Drive – Incubus Drops of Jupiter – Train Dumb Things – Paul Kelly Every Morning – Sugar Ray Phone: 1300 738 735 Address: Level 9, 440 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria, 3000, Australia 1300 738 735 phone [email protected] email -

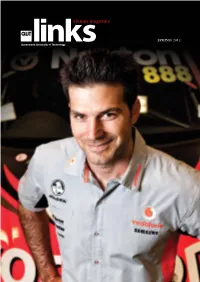

QUT Links Alumni Magazine Spring 2012

alumni magazine SPRING 2012 contentsVOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 Profiles Features Wayne Blair’s The QUT’s Outstanding Sapphires lauded by film Alumni Award winners 9 critics and audiences. 1-6 are revealed. Mother-daughter maths Welcome to the future teaching duo go bush. of interactive learning – 14 11 The Cube. Attorney General Jarrod Bleijie has legislative Bouquets of caring 15 reform on his agenda. recognise Queensland 20 community gems. 4 Student leader Erin Gregor is an impressive 19 all-rounder. Research Regulars New frontier opens for NEWS ROUNDUP 8 10 space glass. RESEARCH UPDATE 18 Rats inspire GPS camera ALUMNI NEWS 21-23 9 technology. 12 KEEP IN TOUCH 24 Heart attack care study LAST WORD rates towns nationwide. 13 by Vice-Chancellor Professor Peter Coaldrake Vice-Chancellor fellows lead the pack in - SEE INSIDE BACK COVER 16 innovative research. Transcend physical and spiritual limits 17 through sport. 17 alumni magazine links Editor Stephanie Harrington p: 07 3138 1150 e: [email protected] Contributors Rose Trapnell Alita Pashley Niki Widdowson Mechelle McMahon Rachael Wilson Images Erika Fish In focus Design Richard de Waal Philanthropist Tim Fairfax is QUT’s distinguished QUT Links is published by QUT’s 7 new Chancellor. Marketing and Communication Department in cooperation with QUT’s Alumni and Development Office. Editorial material is gathered from a range of sources and does not necessarily reflect the opinions and policies of QUT. CRICOS No. 00213J QUTLINKS SPRING ’12 1 Outstanding Young Alumnus Award Winner Mark Dutton Thinker WHEN reigning V8 Supercars champion Jamie Whincup speeds off at the start line, Mark Dutton’s FAST feet are planted firmly on the ground. -

CHICAGO to Tour Australia in 2009 with a Stellar Cast

MEDIA RELEASE Embargoed until 6pm November 12, 2008 We had it coming…CHICAGO to tour Australia in 2009 with a stellar cast Australia, prepare yourself for the razzle-dazzle of the hit musical Chicago, set to tour nationally throughout 2009 following a Gala Opening at Brisbane‟s Lyric Theatre, QPAC. Winner of six Tony Awards®, two Olivier Awards, a Grammy® and thousands of standing ovations, Chicago is Broadway‟s longest-running Musical Revival and the longest running American Musical every to play the West End. It is nearly a decade since the “story of murder, greed, corruption, violence, exploitation, adultery and treachery” played in Australia. Known for its sizzling score and sensational choreography, Chicago is the story of a nightclub dancer, a smooth talking lawyer and a cell block of sin and merry murderesses. Producer John Frost today announced his stellar cast: Caroline O’Connor as Velma Kelly, Sharon Millerchip as Roxie Hart, Craig McLachlan as Billy Flynn, and Gina Riley as Matron “Mama” Morton. “I‟m thrilled to bring back to the Australian stage this wonderful musical, especially with the extraordinary cast we have assembled. Velma Kelly is the role which took Caroline O‟Connor to Broadway for the first time, and her legion of fans will, I‟m sure, be overjoyed to see her perform it once again. Sharon Millerchip has previously played Velma in Chicago ten years ago, and since has won awards for her many musical theatre roles. She will be an astonishing Roxie. Craig McLachlan blew us all away with his incredible audition, and he‟s going to astound people with his talent as a musical theatre performer. -

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-819

Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-819 PDF version Ottawa, 5 November 2010 Revised content categories and subcategories for radio This regulatory policy revises the list of content categories and subcategories for radio by adding a new subcategory 36 (Experimental Music), as announced in Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-499 which sets out the new policy for campus and community radio. This regulatory policy will take effect only when the Radio Regulations, 1986 are amended to make reference to it. 1. In Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-499, which sets out the new policy for campus and community radio, the Commission announced its intention to revise the content categories and subcategories for radio by adding a new subcategory 36 (Experimental Music). The Commission indicated that, in interpreting the new definition of Experimental Music, it would rely on the definitions of musique actuelle, electro acoustic and sound ecology set out in the appendix to Broadcasting Notice of Consultation 2009- 418, as well as the Turntablism and Audio Art Study 2009, which was prepared to assist parties in preparing their comments for the review of campus and community radio. The Commission also provided clarification as to how it would measure the Canadian content of musical selections falling into this new subcategory at paragraphs 77 and 78 of Broadcasting Regulatory Policy 2010-499. 2. In order to implement this determination, the content categories and subcategories contained in the appendix to this regulatory policy, including the new definition of Experimental Music, will replace the content categories set out in the appendix to Public Notice 2000-14. The Commission will propose amendments to the Radio Regulations, 1986 for the purpose of removing all references to the appendix to Public Notice 2000-14 and replacing them with references to the appendix to this regulatory policy.