Thesis Submitted for the Award of the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

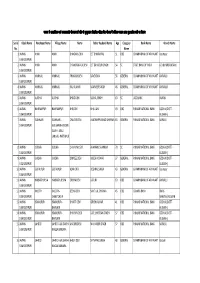

Rural List of Labharthi Parakh.Xlsx

tuin es ykHkkFkhZijd ,oa dY;k.kdkjh ;kstukUrxrZ ifr dh eqR;qijkUr fujkfJr efgyk isaku ;kstuk esa loZs{k.k mijkUr izkIr gq, izkFkZuk i=ksa dk fooj.k Serial Block Name Panchayat Name Village Name Name father husband Name Age Category Bank Name Branch Name No. Name 1 JAWAN AHAK AHAK BHAGVAN DEVI LET DHARM PAL 51 OBC GRAMIN BANK OF ARYAVART Kasimpur SIKANDERPUR 2 JAWAN AHAK AHAK CHANDRAKALA DEVI LET BAHADUR SINGH 54 SC STATE BANK OF INDIA A.D.B.HARDUAGANJ SIKANDERPUR 3 JAWAN AMRAULI AMRAULI PRAKASH DEVI RAVENDRA 56 GENERAL GRAMIN BANK OF ARYAVART AMRAULI SIKANDERPUR 4 JAWAN AMRAULI AMRAULI RAJ KUMARI RAMVEER SINGH 46 GENERAL GRAMIN BANK OF ARYAVART AMRAULI SIKANDERPUR 5 JAWAN AURIHA AURIHA BHOO DEVI RAJPAL SINGH 63 SC UCO BANK JAWAN SIKANDERPUR 6 JAWAN BAHRAMPUR BAHRAMPUR BHUDEVI BHULLAN 43 OBC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK GODHA (DISTT- SIKANDERPUR ALIGARH) 7 JAWAN GANWARI GANWARI-- OMVATI DEVI JAGDISH PRASHAD SHARMA 63 GENERAL PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK BARAULI SIKANDERPUR GOLGARHI-MADAN GARHI--ARAJI JANGAL--PARTAPUR 8 JAWAN GODHA GODHA CHAINIYA DEVI BHAWANI SHANKAR 70 SC PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK GODHA (DISTT- SIKANDERPUR ALIGARH) 9 JAWAN GODHA GODHA DOPDEE DEVI RAJESH KUMAR 37 GENERAL PUNJAB NATIONAL BANK GODHA (DISTT- SIKANDERPUR ALIGARH) 10 JAWAN GOPALPUR GOPALPUR ASHA DEVI DESHRAJ SINGH 43 GENERAL GRAMIN BANK OF ARYAVART Kasimpur SIKANDERPUR 11 JAWAN HAIBATPUR SIA HAIBATPUR SIYA DROPA DEVI LATURI 63 OBC GRAMIN BANK OF ARYAVART AMRAULI SIKANDERPUR 12 JAWAN IMLOTH IMLOTH-- BEENA DEVI SANT LAL SHARMA 45 OBC CANARA BANK VIKAS SIKANDERPUR CHANTOKHA BHAVAN/ALIGARH -

Aligarh District, Uttar Pradesh

कᴂ द्रीय भूमम जऱ बो셍 ड जऱ संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण मंत्राऱय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Ministry of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation Government of India Report on AQUIFER MAPPING AND GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT PLAN Aligarh District, Uttar Pradesh उत्तरीक्षेत्र , ऱखनऊ Northern Region, Lucknow For Restricted/ Authorized Official Use Only Government of India Ministry of Water Resources, River Development & Ganga Rejuvenation Central Ground Water Board Northern Region, Hkkjr ljdkj ty lalk/ku] unh fodkl vkSj xaxk laj{k.k ea=ky; dsUnzh; Hkwfety cksMZ mRrjh {ks= Interim Report AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, UTTAR PRADESH By Dr. Seraj Khan Scientist “D’ Lucknow, April 2017 AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2016-2017) By Dr Seraj Khan Scientist 'D' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 OBJECTIVE 1 1.2 SCOPE OF STUDY 1 1.3 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3 1.4 STUDY AREA 3 1.5 DEMOGRAPHY 4 1.6 DATA AVAILABILITY & DATA GAP ANALYSIS 5 1.7 URBAN AREA INDUSTRIES AND MINING ACTIVITIES 6 1.8 LAND USE, IRRIGATION AND CROPPING PATTERN 6 1.9 CLIMATE 13 1.10 GEOMORPHOLOGY 17 1.11 HYDROLOGY 19 1.12 SOIL CHARACTERISTICS 20 2.0 DATA COLLECTION, GENERATION, INTERPRETATION, INTEGRATION 22 AND AQUIFER MAPPING 2.1 HYDROGEOLOGY 22 2.1.1 Occurrence of Ground Water 22 2.1.2 Water Levels: 22 2.1.3 Change in Water Level Over the Year 28 2.1.4 Water Table 33 2.2 GROUND WATER QUALLIY 33 2.2.1 Results Of Basic Constituents 37 2.2.2 Results Of Heavy Metal 44 2.2.3 -

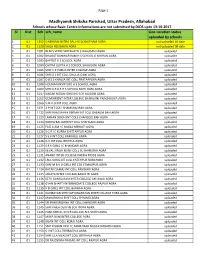

Center Information Not Updated by DIOS 13102017.Xlsx

Page 1 Madhyamik Shiksha Parishad, Uttar Pradesh, Allahabad Schools whose Basic Centre Informations are not submitted by DIOS upto 13-10-2017 Sl Dist Sch sch_name Geo-Location status uploaded by schools 1 01 1352 S NEKRAM NETRA PAL H S SCH KITHAM AGRA not uploaded till date 2 01 1620 SHILA HSS BAGIA AGRA not uploaded till date 3 01 1001 BENI S VEDIC VIDYAVATI I C BALUGANJ AGRA uploaded 4 01 1002 BHAGAT KANWAR RAM H S SCHOOL G M KHAN AGRA uploaded 5 01 1003 BAPTIST H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 6 01 1004 CHITRA GUPTA H S SCHOOL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 7 01 1005 SHRI C P PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE AGRA uploaded 8 01 1006 SHRI D J INT COLL DHULIA GANJ AGRA uploaded 9 01 1007 D B S S KHALSA INT COLL PRATAPPURA AGRA uploaded 10 01 1008 HOLMAN INSTITUTE H S SCHOOL AGRA uploaded 11 01 1009 SHRI K R B R H S SCHOOL MOTI GANJ AGRA uploaded 12 01 1037 NAGAR NIGAM GIRLS HS SCH TAJGANJ AGRA uploaded 13 01 1052 GOVERMENT INTER COLLEGE SHAHGANJ PNACHKUIYA AGRA uploaded 14 01 1066 S M A O INT COLL AGRA uploaded 15 01 1071 A P INT COLL SHAMSHADBAD AGRA uploaded 16 01 1122 SHRI RAM SAHAY VERMA INT COLL BASAUNI BAH AGRA uploaded 17 01 1123 LAKHAN SINGH INT COLL CHANGOLI BAH AGRA uploaded 18 01 1124 RADHA BALLABH INT COLL SHAHGANJ AGRA uploaded 19 01 1125 FAIZ A AM I C NAGLA MEWATI AGRA uploaded 20 01 1126 S G R I C KURRA CHITTARPUR AGRA uploaded 21 01 1127 S S V INT COLL KARKAULI AGRA uploaded 22 01 1128 G V INT COLL BRITHLA AGRA uploaded 23 01 1129 S R K GIRLS I C KHANDARI AGRA uploaded 24 01 1130 KEVAL SINGH M INT COLL SUTHARI BAH AGRA uploaded 25 01 1131 ANAND INTER -

Aligarh District, U.P

GROUND WATER BROCHURE ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By SAIDUL HAQ Scientist 'B' CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD NORTHERN REGION LUCKNOW, UP MAY 2013 GROUND WATER BROCHURE OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By SAIDUL HAQ Scientist 'B' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. ALIGARH DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................6 1.1 Land Use 1.2 Studies / Activities Carried Out by CGWB 2.0 RAINFALL & CLIMATE ..................8 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY ..................9 3.1 Physiography 3.2 Drainage 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................9 4.1 Geology 4.2 Ground Water Exploration 4.3 Hydro-geological Setup 4.4 Aquifer Parametres 4.5 Hydrogeology 4.6 Seasonal Fluctuation 4.7 Long Term Water Level Trends 4.8 Ground Water Resources 4.9 Ground Water Quality 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................21 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation & Artificial Recharge 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ..................22 6.1 Water Logged Areas 6.2 Ground Water Polluted Area 7.0 AWARENESS & TRAINING ACTIVITY ..................23 8.0 AREA NOTIFIED BY CGWB / SGWA ..................23 9.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................23 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. II. PRE-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER MAP (MAY 2012), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. III. POST-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER MAP (NOVEMBER 2012), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. IV. WATER LEVEL FLUCTUATION MAP (NOVEMBER 2012 – MAY 2012) V. WATER LEVEL DECADAL TREND ( 2003 – 2012) VI. GROUND WATER RESOURCE (AS ON 31.03.2009), DISTRICT ALIGARH, U.P. VII. HYDROGEOLOGICAL MAP OF ALIGARH DISTRICT, U.P. -

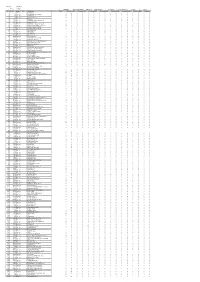

CLUSTER 1 AO DELHI 1 Total Engineers Field Resident 19 4 15

CLUSTER 1 AO DELHI 1 Total EngineersField Resident 19 4 15 DESKTOPS Printer inkjet/MONO Printer laser printerall in one Draft printer Passbook Printer Scanner Laptop SNO Br Code Module RGN Branch Name AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty AMC Warranty 1 737 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 PAHARGANJ DELHI 0 11 0 0 1 0 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 745 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 SME DELHI BRANCH ASAF ALI ROAD 8 9 0 0 2 0 4 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 1187 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 I.P.ESTATE,DELHI DELHI 5 5 0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 1270 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 DARYA DELHI GANJ, DELHI 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 5 1274 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 JANGPURA DELHI 4 5 0 0 3 0 2 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 6 1537 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 CANNAUGHT DELHI CIRCUS, NEW DELHI 6 4 0 0 2 0 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 3702 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 SANSADIYA DELHI SOUDH 2 9 0 0 0 0 1 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 4076 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 PARLIAMENT DELHI HOUSE, NEW DELHI 1 7 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 4281 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 RAJGHAT DELHI POWER HOUSE, NEW DELHI 9 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 10 4730 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 DDA DELHI BUILDING, NEW DELHI 3 5 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11 6199 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 JAWAHAR DELHI VYAPAR BHAWAN 4 9 0 0 1 0 3 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 12 6564 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 IOC DELHI LODHI ROAD 4 3 0 0 0 0 2 0 2 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 13 7837 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 CGO DELHI COMPLEX 7 9 0 0 2 0 3 0 2 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 14 9109 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 NIZAMMUDIN DELHI 2 8 0 0 1 0 3 0 1 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 15 10623 AO-1 SOUTH AND EAST1 INS DELHI NEW DELHI 1 6 0 0 0 1 -

Urban Influence on Rural Economy in Aligarh District, Up

URBAN INFLUENCE ON RURAL ECONOMY IN ALIGARH DISTRICT, UP. ABSTRACT Thesis Submitted For The Degree Of factor of ^liiloiop^p IN GEOGBAPHY To THE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH By HSoliicl. XmlckvcLt Saeed Kban DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1993 URBAN INPLUBNCB ON RURAL SCONQMY IN V •XV ABSTRACT rV 1 • , aural India ia transforming at a raTp^cf^^^^e". xXucii of this transformation is the result of urban impact that is being f©lt even at great distances. As a result of this process, basis of traditionally self-sufficient village economy is being increasingly eroded by the market oriented production. The change in the mode of production in rural economy is bringing change in the overall socio-economic setup of the countryside. In this context the degree of urbanisation in an area is thought to be an index of change in the nirul economy. The theme of the present investigation is centred on the urban influence on rural economy. The relationship between the two is conceptualised and tested taking Koll Tshsll of Aligai* District, Uttar Pradesh as a case study. During the course of investigation the author has tried to examine the nature of changes in rural economy by rural-urban inteructlon and to find out the most important determinants oi urban influence in the countryside. These avowed alms have guided and guaged the present Investigation. Aligarh City enjoys a central position as the district headquarter, where a number of administrative function and their offices are located. Besides, the presence ot Industrial -2- units, educational inBtitutions, commercial eetabliehmentB, traneportational facilities and the social and cultural inatitutiona have made it into a town of regional importance in and outaide the district. -

Aligarh Page:- 1 Cent-Code & Name Exam Sch-Status School Code & Name #School-Allot Sex Part Group 1001 Naurangi Lal Govt Inter College Aligarh Aum

DATE:27-02-2021 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 **** FINAL CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT **** DIST-CD & NAME :- 06 ALIGARH PAGE:- 1 CENT-CODE & NAME EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1001 NAURANGI LAL GOVT INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH AUM HIGH BUM 1040 L N S INT COLL QUARSI ALIGARH 67 M HIGH CRM 1047 S B B M INT COLL ALIGARH 12 F HIGH CRM 1133 S T S B INT COLL BHOOP SINGH NAGAR JWALAGARH ALIGARH 72 M HIGH CUM 1153 S S NIKETAN HIGH SCH RAMGHAT RD ALIGARH 5 F HIGH CUM 1189 S BASUDEV H S S M NAGAR ALIGARH 8 F HIGH CRM 1274 GRAMODAYA HR SEC SCH MAHARAWAL ALIGARH 40 M HIGH CRM 1448 AHILYABAI HOLKAR HSS CHANDAUKHA ALIGARH 27 M HIGH CUF 1481 LOUISA SOULES GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ALIGARH 26 F HIGH CRM 1528 B S HSS NAGLA PIPAL UDAY VIHAR COLONEY ALIGARH 17 M HIGH CUM 1540 S K INTER COLLEGE JAIGANJ ROAD ALIGARH 12 F HIGH CUM 1639 SUNRISE PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE MANZOORGARHI ALIGARH 31 M HIGH CUM 1651 S M HIGH SCHOOL JWALAPURI ALIGARH 18 F HIGH CUM 1728 OSHO MEMORIAL INTERNATIONAL COLL SURYAVIHAR ALIGARH 5 F HIGH AUM 5001 NAURANGI LAL GOVT INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 2 F 342 INTER BUM 1004 HEERALAL BARAHSAINI INT COLL ALIGARH 155 M - OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUM 1008 RAGHUVEER SAHAI INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 102 M SCIENCE INTER BUM 1008 RAGHUVEER SAHAI INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 111 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1044 MODERN CONVENT INTER COLLEGE RAMGHAT ROAD ALIGARH 43 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1195 S C S L A I C ALAPUR GARIYA ALIGARH 10 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1775 A N P INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 55 M SCIENCE 476 CENTRE TOTAL >>>>>> 818 1002 S M B -

1001 Naurangi Lal Govt Inter College Aligarh A

PAGE:- 1 BHS&IE, UP EXAM YEAR-2021 *** PROPOSED CENTRE ALLOTMENT REPORT (UPDATED BY DISTRICT COMMITTEE) *** DIST-CD & NAME:- 06 ALIGARH DATE:- 14/02/2021 CENT-CODE & NAME CENT-STATUS CEN-REMARKS EXAM SCH-STATUS SCHOOL CODE & NAME #SCHOOL-ALLOT SEX PART GROUP 1001 NAURANGI LAL GOVT INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH A HIGH BUM 1040 L N S INT COLL QUARSI ALIGARH 67 M HIGH CRM 1047 S B B M INT COLL ALIGARH 12 F HIGH CRM 1133 S T S B INT COLL BHOOP SINGH NAGAR JWALAGARH ALIGARH 72 M HIGH CUM 1153 S S NIKETAN HIGH SCH RAMGHAT RD ALIGARH 5 F HIGH CUM 1189 S BASUDEV H S S M NAGAR ALIGARH 8 F HIGH CRM 1274 GRAMODAYA HR SEC SCH MAHARAWAL ALIGARH 40 M HIGH CRM 1448 AHILYABAI HOLKAR HSS CHANDAUKHA ALIGARH 27 M HIGH CUF 1481 LOUISA SOULES GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL ALIGARH 26 F HIGH CRM 1528 B S HSS NAGLA PIPAL UDAY VIHAR COLONEY ALIGARH 17 M HIGH CUM 1540 S K INTER COLLEGE JAIGANJ ROAD ALIGARH 12 F HIGH CUM 1639 SUNRISE PUBLIC INTER COLLEGE MANZOORGARHI ALIGARH 31 M HIGH CUM 1651 S M HIGH SCHOOL JWALAPURI ALIGARH 18 F HIGH CUM 1728 OSHO MEMORIAL INTERNATIONAL COLL SURYAVIHAR ALIGARH 5 F HIGH AUM 5001 NAURANGI LAL GOVT INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 2 F 342 INTER BUM 1004 HEERALAL BARAHSAINI INT COLL ALIGARH 155 M IInd - PART OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER BUM 1008 RAGHUVEER SAHAI INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 102 M SCIENCE INTER BUM 1008 RAGHUVEER SAHAI INTER COLLEGE ALIGARH 111 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1044 MODERN CONVENT INTER COLLEGE RAMGHAT ROAD ALIGARH 43 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CRM 1195 S C S L A I C ALAPUR GARIYA ALIGARH 10 M OTHER THAN SCICNCE INTER CUM 1775 A N P INTER COLLEGE -

29 5 2019 15 52 32 5-Merit-List

GENERAL (OTHER THEN MRATAK ASHRIT & O LEVEL) FIFTH MERIT LIST Father's Obtain Total Date of EX- ARDH- MRATAK SR NO. Name Address MobileNo AadhaarNo Marks% RefNo. Caste Amt NCC ITI A LEVEL RETIRE O LEVEL Name Marks Marks Birth ARMY SAINIK ASHRIT UDAY VILL-GAURA BIBI PUR POST-KADIPUR 1002 SATYAM PRATAP DIST-SULTANPUR UTTAR PARDESH NOIDA- SINGH SINGH 228145 7379258879 994024984934 358 500 71.6 15-Jul-96 7991 General 200 YES RAMLAKHA 1003 SHIVAM N NOIDA- BHADORIA BHADORIA REKHA NAGAR WARD NO.25 BHIND 8370087577 463271588418 358 500 71.6 01-Apr-97 4652 General 200 YES VILLAGE- NASIRPUR DIGOLI, POST- 1004 SHUBHAM RAVINDRA NAGAL, DIST- SAHARANPUR, PIN- NOIDA- TYAGI TYAGI 247551 8393975609 770700327468 358 500 71.6 01-Aug-97 9676 General 200 YES 1005 AVDHESH KOMAL VILL PACHAWARI POST BISAWAR TEH NOIDA- KUMAR PRASAD SADABAD DIST HATHRAS PIN 281302 6395640308 606991363087 358 500 71.6 10-Oct-97 6457 General 200 YES 1006 krishan hari Rajesh NOIDA- chaudhary chaudhary vill.gajpur post.gajpur dist.gorakhpur 7068623234 655209225374 358 500 71.6 21-Oct-97 1344 General 200 YES JATIN KAILASH GALI NO 04 SHIVAJI PURAM NOIDA- 1007 KUMAR CHAND INDERGARHI GHAZIABAD 9555363761 963007763516 358 500 71.6 21-May-98 4994 General 200 YES VILLAGE-MUKIMPUR BALU URF 1008 LALIT BHAGAIN POST-MANGOLPURA STATE- NOIDA- KUMAR KELA SINGH UP PINCODE-246701 7088338312 366549140729 716 1000 71.6 04-May-00 12304 General 200 YES VILL SARAI HARKHU POST SARAI 1009 HIMANSHU SUNIL HARKHU TEH BADLAPUR DISTRICT NOIDA- SRIVASTAV SRIVASTAV JAUNPUR PIN CODE 222141 9936838505 333978947569 -

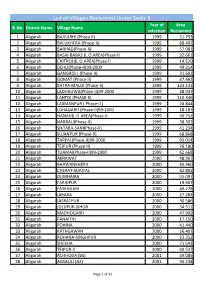

List of Villages Reclaimed Under Sodic II Year of Area Sl.No

List of Villages Reclaimed Under Sodic II Year of Area Sl.No. District Name Village Name selection Reclaimed 1 Aligarah BAJGARHI (Phase II) 1999 51.753 2 Aligarah BALUKHERA (Phase-II) 1999 68.492 3 Aligarah BARHAD(Phase-II) 1999 57.081 4 Aligarah BASAI-BABAS (L.O.AREA)Phase-II 1999 32.661 5 Aligarah CHITROLI(L.O.AREA)Phase-II 1999 14.520 6 Aligarah DEHLI(Phase-II)99-2000 1999 49.214 7 Aligarah GANGROLL (Phase-II) 1999 31.602 8 Aligarah GOMAT (Phase-II) 1999 67.462 9 Aligarah KATRA-MALOI (Phase-II) 1999 123.131 10 Aligarah LADHAUWA(Phase-II)99-2000 1999 28.937 11 Aligarah LAHTOI (PHASE-II) 1999 110.346 12 Aligarah LAXMANPUR ( Phase-II ) 1999 28.844 13 Aligarah LOHAGARH (Phase-II)99-2000 1999 18.183 14 Aligarah NANAU(L.O.AREA)Phase-II 1999 40.752 15 Aligarah NARRAU(Phase-II) 1999 38.302 16 Aligarah SIKTARA-SANI(Phase-II) 1999 41.234 17 Aligarah SUJANPUR (Phase-II) 1999 68.868 18 Aligarah TAPPAL(Phase-II)99-2000 1999 93.014 19 Aligarah TEJPUR (Phase-II) 1999 26.180 20 Aligarah TUAMAI(Phase-II)99-2000 1999 62.668 21 Aligarah AKRAWAT 2000 48.907 22 Aligarah BHAWANKHERA 2000 40.960 23 Aligarah CHERAT-SURIYAL 2000 42.802 24 Aligarah DUMHAIRA 2000 55.097 25 Aligarah FARIDPUR 2000 19.607 26 Aligarah FATEHGARI 2000 49.276 27 Aligarah JARARA 2000 27.284 28 Aligarah JASRATPUR 2000 30.586 29 Aligarah JULUPUR-SIHOR 2000 34.511 30 Aligarah MADHOGARH 2000 47.992 31 Aligarah PANAITHI 2000 17.150 32 Aligarah POHINA 2000 41.440 33 Aligarah RATHGAWAN 2000 56.401 34 Aligarah ROHANA-SINGHPUR 2000 23.352 35 Aligarah SHEKHA 2000 71.543 36 Aligarah TEJPUR-II 2000 60.537 37 Aligarah ACHHODA (BS) 2001 49.085 38 Aligarah AGSAULI (A2) 2001 94.238 Page 1 of 95 List of Villages Reclaimed Under Sodic II Year of Area Sl.No. -

Changing Paradigms of Gender Inequality in Uttar Pradesh: a Study of Jawan Block (District Aligrh)

CHANGING PARADIGMS OF GENDER INEQUALITY IN UTTAR PRADESH: A STUDY OF JAWAN BLOCK (DISTRICT ALIGRH) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT By the grace of Almighty God I am able to complete my work with great satisfaction and able to submit it for the award of Ph.D. degree. In this process Professor Noor Mohammad became instrumental by guiding me at every level of this work. Really I am indebted to him for his kind and generous support which he showed on me without any botheration of time and energy. I don‘t find words to express my gratitude and indebtedness. Due to instant support and guidance from him I never felt that I am an orphan. My deepest thanks to Prof. Noor Mohammad for his constant supervision, intellectual input and brilliant guidance throughout the duration of the present research work. I am product of the Department of Sociology and Social work, AMU, Aligarh and have been receiving help and support from other faculties of the Department of Sociology & Social Work from time to time– Dr. Abdul Matin, Chairman, Dr. Nikhat Firoz, Dr. Zainuddin, Dr. Abdul Waheed, Dr. P.K. Mathur, Late Dr. Nemat Ali Khan, Dr. Naseem Ahmad Khan, Dr. Mohammad Akram, Dr. Shirin Sadiq, Dr. Sameena. I thanks them all because whatever I am today, it is because of them. Office staff of this Department have always been cooperative and provided me all support during my stay here. They never gave me any opportunity to have a feeling of neglect and deprivation. My thanks are to them all. I will be failing in my duty if I don‘t mention the name of my uncle Late Mr. -

Ground Water Quality in Shallow Aquifers of India

GROUND WATER QUALITY IN SHALLOW AQUIFERS OF INDIA CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA FARIDABAD 2010 GROUND WATER QUALITY IN SHALLOW AQUIFERS OF INDIA CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES GOVERNMENT OF INDIA FARIDABAD 2010 FOREWORD Ground water has become one of the important sources of water for meeting the requirements of various sectors in the country in the last few decades. It plays a vital role in India’s economic development and in ensuring its food security. The rapid pace of agricultural development, industrialization and urbanization has resulted in the over- exploitation and contamination of ground water resources in parts of the country, resulting in various adverse environmental impacts and threatening its long-term sustainability. The ground water available in the country, in general, is potable and suitable for various usage. However, localized occurrence of ground water having various chemical constituents in excess of the limits prescribed for drinking water use has been observed in almost all the states. The commonly observed contaminants such as Arsenic, Fluoride and Iron are geogenic, whereas contaminants such as nitrates, phosphates, heavy metals etc. owe their origin to various human activities including domestic sewerage, agricultural practices and industrial effluents. The quality aspects of ground water in the country is being monitored by the Central Ground Water Board through a network of about 15500 ground water observation wells, from which samples are collected and analyzed during the month of May every year. Ground water quality data is also being collected by the Board as part of its other activities such as ground water management studies, exploratory drilling programme, special studies on water quality etc.